RAJIC-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![372] CHENNAI, MONDAY, NOVEMBER 20, 2017 Karthigai 4, Hevilambi, Thiruvalluvar Aandu-2048](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8835/372-chennai-monday-november-20-2017-karthigai-4-hevilambi-thiruvalluvar-aandu-2048-78835.webp)

372] CHENNAI, MONDAY, NOVEMBER 20, 2017 Karthigai 4, Hevilambi, Thiruvalluvar Aandu-2048

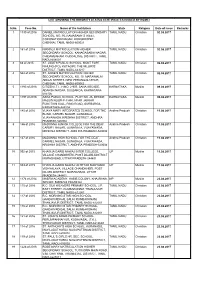

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2017 [Price: Rs. 8.00 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 372] CHENNAI, MONDAY, NOVEMBER 20, 2017 Karthigai 4, Hevilambi, Thiruvalluvar Aandu-2048 Part II—Section 2 Notifi cations or Orders of interest to a section of the public issued by Secretariat Departments. NOTIFICATIONS BY GOVERNMENT HIGHWAYS AND MINOR PORTS DEPARTMENT NOTICE ACQUISITION OF LANDS Under sub-section (1) of Section 15 of the Tamil Nadu [G.O. (D). No. 261, Highways and Minor Ports (HN2), Highways Act, 2001 (Tamil Nadu Act 34 of 2002), the Governor 20th November 2017, 裘ˆF¬è 4, «ýM÷‹H, F¼õœÀõ˜ ݇´-2048.] of Tamil Nadu hereby acquires the dry and manai lands specifi ed in the Schedule below and measuring to an extent No.II(2)/HWMP/935(e-1)/2017. of 914 Sq.mtrs in Kilathayanoor, Kulapakkam (Aviyur), The Governor of Tamil Nadu having satisfi ed that the Sithilingamadam (West) Villages in Thirukovilur Taluk and lands specifi ed in the Schedule below are acquired under Saravanampakkam Village in Ulundurpet Taluk Villupuram TNRSP-II Highways purpose, to wit for upgrading Cuddalore District to the same, a little more or less needed for TNRSP-II – Chittoor Road (SH 09) at Km 41/700 to Km 44/000 & Km Highways purpose, to wit for upgrading Cuddalore – Chittoor 45/000 to Km 66/190 and formation of a new link road between SH 09 & SH 137 (Km 66/190 to Km 71/147 in Kilathayanoor, Road (SH 09) at Km 41/700 to 44/000 & Km 45/000 to Km Kulapakkam (Aviyur), Sithilingamadam (West) Villages 66/190 and formation of a new link road between SH09 & in Thirukovilur Taluk and Saravanampakkam Village in SH 137 (Km 66/190 to Km 71/147). -

Socio–Cultural Elimination and Insertion of Trans-Genders in India

[ VOLUME 6 I ISSUE 2 I APRIL– JUNE 2019] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 Socio–cultural elimination and insertion of trans-genders in India Dr.Rathna Kumari K R Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Government First Grade College, HSR Layout, Bangalore, Karnataka, India. Received: February 09, 2019 Accepted: March 22, 2019 ABSTRACT: With an increasing issues in India, one of the major social issues concerning within the country is the identity of transgender. Over a decade in India, the issue of transgender has been a matter of quest in both social and cultural context where gender equality still remains a challenging factor towards the development of society because gender stratification much exists in every spheres of life as one of the barriers prevailing within the social structure of India. Similarly the issue of transgender is still in debate and uncertain even after the Supreme of India recognise them as a third gender people. In this paper I express my views on the issue of transgender in defining their socio – cultural exclusion and inclusion problems and development process in the society, and Perceptions by the main stream. Key Words: INTRODUCTION The term transgender / Hijras in India can be known by different terminologies based on different region and communities such as 1. Kinnar– regional variation of Hijras used in Delhi/ the North and other parts of India such as Maharashtra. 2. Aravani – regional variation of Hijras used in Tamil Nadu. Some Aravani activists want the public and media to use the term 'Thirunangi' to refer to Aravanis. 3. Kothi - biological male who shows varying degrees of 'femininity.' Some proportion of Hijras may also identify themselves as 'Kothis,' but not all Kothis identify themselves as transgender or Hijras. -

District at a Glance 2016-17

DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 2016-17 I GEOGRAPHICAL POSITION 1 North Latitude Between11o38’25”and 12o20’44” 2 East Longitude Between78o15’00”and 79o42’55” 3 District Existence 18.12.1992 II AREA & POPULATION (2011 census) 1 Area (Sq.kms) 7194 2 Population 34,58,873 3 Population Density (Sq.kms) 481 III REVENUE ADMINISTRATION (i) Divisions ( 4) 1 Villupuram 2 Tindivanam 3 Thirukovilur 4 Kallakurichi (ii) Taluks (13) 1 Villupuram 2 Vikkaravandi (Existancefrom12.02.2014) 3 Vanur 4 Tindivanam 5 Gingee 6 Thirukovilur 7 Ulundurpet 8 Kallakurichi 9 Chinnaselam(Existancefrom12.10.2012) 10 Sankarapuram 11 Marakkanam(Existancefrom04.02.2015) 12 Melmalaiyanur (Existancefrom10.02.2016 13 Kandachipuram(Existancefrom27.02.2016) (iii) Firkas 57 (iv) Revenue Villages 1490 1 IV LOCAL ADMINISTRATION (i) Municipalities (3) 1 Villupuram 2 Tindivanam 3 Kallakurichi (ii) Panchayat Unions (22) 1 Koliyanur 2 Kandamangalam 3 Vanur 4 Vikkaravandi 5 Kanai 6 Olakkur 7 Mailam 8 Marakkanam 9 Vallam 10 Melmalaiyanur 11 Gingee 12 Thiukovilur 13 Mugaiyur 14 Thiruvennainallur 15 Ulundurpet 16 Thirunavalur 17 Kallakurichi 18 Chinnaselam 19 Sankarapuram 20 Thiyagadurgam 21 Rishivandiyam 22 KalvarayanMalai (iii) Town Panchayats (15) 1 Vikkaravandi 2 Valavanur 3 Kottakuppam 4 Marakkanam 5 Gingee 6 Ananthapuram 7 Manalurpet 8 Arakandanallur 9 Thirukoilur 10 T.V.Nallur 11 Ulundurpet 12 Sankarapuram 13 Vadakkanandal 14 Thiyagadurgam 15 Chinnaselam (iv) VillagePanchayats 1099 2 V MEDICINE & HEALTH 1 Hospitals ( Government & Private) 151 2 Primary Health centres 108 3 Health Sub centres 560 4 Birth Rate 14.8 5 Death Rate 3.6 6 Infant Mortality Rate 11.1 7 No.of Doctors 682 8 No.of Nurses 974 9 No.of Bed strength 3597 VI EDUCATION 1 Primary Schools 1865 2 Middle Schools 506 3 High Schools 307 4 Hr. -

Sl. NO. Name of the Guide Name of the Research Scholar Reg.No Title Year of Registration Discipline 1. Dr.V.Rilbert Janarthanan

Sl. Year of Name of the Guide Name of the Research Scholar Reg.No Title Discipline NO. registration Dr.V.Rilbert Janarthanan Mr.K.Ganesa Moorthy Gjpdz; fPo;f;fzf;F Asst.Prof of Tamil 103D,North Street 1. 11001 Ey;fSk; r*fg; gz;ghl;L 29-10-2013 Tamil St.Xaviers College Arugankulam(po),Sivagiri(tk) khw;Wk; gjpTfSk; Tirunelveli Tirunelveli-627757 Dr.A.Ramasamy Ms.P.Natchiar Prof & HOD of Tamil 22M.K Srteet vallam(po) 11002 vLj;Jiug;gpay; 2. M.S.University 30-10-2013 Tamil Ilangi Tenkasi(tk) (Cancelled) Nehf;fpd; rpyg;gjpf;fhuk; Tvl Tvl-627809 627012 Dr.S.Senthilnathan Mr.E.Edwin Effect of plant extracts and its Bio-Technology Asst.Prof 3. Moonkilvillai Kalpady(po) 11003 active compound against 30-10-2013 Zoology SPKCES M.S.University Kanyakumari-629204 stored grain pest (inter disciplinary) Alwarkurichi Tvl-627412 Dr.S.Senthilnathan Effect of medicinal plant and Mr.P.Vasantha Srinivasan Bio-Medical genetics Asst.Prof entomopatho generic fungi on 4. 11/88 B5 Anjanaya Nagar 11004 30-10-2013 Zoology SPKCES M.S.University the immune response of Suchindram K.K(dist)-629704 (inter disciplinary) Alwarkurichi Tvl-627412 Eepidopternam Larrae Ms.S.Maheshwari Dr.P.Arockia Jansi Rani Recognition of human 1A/18 Bryant Nagar,5th middle Computer Science and 5. Asst.Prof,Dept of CSE 11005 activities from video using 18-11-2013 street Tuticorin Engineering classificaition methods MS University 628008 Dr.P.Arockia Jansi Rani P.Mohamed Fathimal Visual Cryptography Computer Science and 6. Asst.Prof,Dept of CSE 70,MGP sannathi street pettai 11006 20-11-2013 Algorithm for image sharing Engineering MS University Tvl-627004 J.Kavitha Dr.P.Arockia Jansi Rani 2/9 vellakoil suganthalai (po) Combination of Structure and Computer Science and 7. -

S.No. Case No. Name of the Institution State Religion Date of Issue

LIST SHOWING THE MINORITY STATUS CERTIFICATES ISSUED BY NCMEI S.No. Case No. Name of the Institution State Religion Date of Issue Remarks 1 1330 of 2016 DANIEL MATRICULATION HIGHER SECONDARY TAMIL NADU Christian 02.08.2017 SCHOOL, NO. 36, RAMASAMY STREET, CORONATION NAGAR, KORUKKUPET, CHENNAI, TAMIL NADU-600021 2 161 of 2016 NIRMALA MATRICULATION HIGHER TAMIL NADU Christian 02.08.2017 SECONDARY SCHOOL, KANAGASABAI NAGAR, CHIDAMBARAM, CUDDALORE DISTRICT, TAMIL NADU-608001 3 68 of 2015 ST. JUDE’S PUBLIC SCHOOL, MONT FORT, TAMIL NADU Christian 02.08.2017 NIHUNG (PO), KOTAGIRI, THE NILGIRIS DISTRICT, TAMIL NADU-643217 4 544 of 2016 ST. ANNE’S MATRICULATION HIGHER TAMIL NADU Christian 02.08.2017 SECONDARY SCHOOL, NO. 10, MARAIMALAI ADIGAI STREET, NEW PERUNGALATHUR, CHENNAI, TAMIL NADU-600063 5 1193 of 2016 CITIZEN I.T.I., H.NO. 2-907, SANA ARCADE, KARNATAKA Muslim 09.08.2017 ADARSH NAGAR, GULBARGA, KARNATAKA- 585105 6 1197 of 2016 ASRA PUBLIC SCHOOL, PLOT NO. 26, BESIDE KARNATAKA Muslim 09.08.2017 MASJID NOOR-E-ILAHI, NEAR JABBAR FUNCTION HALL, RING ROAD, GURBARGA, KARNATAKA-585104 7 145 of 2016 VIJAYA MARY INTEGRATED SCHOOL FOR THE Andhra Pradesh Christian 11.08.2017 BLIND, CARMEL NAGAR, GUNADALA, VIJAYAWADA, KRISHNA DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH-520004 8 146 of 2016 MADONNA JUNIOR COLLEGE FOR THE DEAF, Andhra Pradesh Christian 11.08.2017 CARMEL NAGAR, GUNADALA, VIJAYAWADA, KRISHNA DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH-520004 9 147 of 2016 MADONNA HIGH SCHOOL FOR THE DEAF, Andhra Pradesh Christian 11.08.2017 CARMEL NAGAR, GUNADALA, VIJAYAWADA, KRISHNA DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH-520004 10 992 of 2015 KHAWJA GARIB NAWAJ INTER COLLEGE, UP Muslim 11.08.2017 VILLAGE CHANDKHERI, POST DILARI, DISTRICT MORADABAD, UTTAR PRADESH-244401 11 993 of 2015 KHAWJA GARIB NAWAJ UCHTTAR MADYAMIK UP Muslim 11.08.2017 VIDHYALAYA, VILLAGE CHANDKHERI, POST DILARI, DISTRICT MORADABAD, UTTAR PRADESH-244401 12 1174 of 2014 MABFM ACADEMY, HABIB COLONY, KHAJRANA, MP Muslim 23.08.2017 INDORE, MADHYA PRADESH 13 115 of 2016 R.C. -

A Transgender's Journey

Journal of Teaching and Research in English Literature An international peer-reviewed open-access journal [ISSN: 0975-8828] Volume 9 – Number 2 – April 2018 Struggle for Existence and Marginalization of the Third Gender in I am Vidya: A Transgender’s Journey Twinkle Dasari [ELTAI Short-term Member – 30015351] Ph.D. Research Scholar, Acharya Nagarjuna University, Andhra Pradesh, India. Email: [email protected] Received: 18 March 2018 Peer-reviewed: 3 April 2018 Resubmitted: 4 April 2018 Accepted: 10 April 2018 Published Online: 30 April 2018 ABSTRACT Gender and sexuality are socially constructed and not natural. Sex is the polarity of anatomy whereas gender is the polarity of appearance and behaviour. Whenever a discussion of gender is presented it mainly takes place about two genders i.e., male and female. The word ‘gender identity’ too might lead one towards feminism. However, there is another gender which is often neglected. It is the third gender i.e., transgenders who are a complex and internally varied group mostly male born and a few biologically intersex persons, who cross-dress and may or may not undergo voluntary castration. The existence of the third gender is as natural as the existence of male or female. But transgenders are looked down with ridicule, disrespect and are marginalized in the society. The present paper is an attempt to analyse the struggle for existence and marginalization of transgenders in the autobiography of Living Smile Vidya, I am Vidya: A Transgender's Journey. KEYWORDS Gender; Identity; Third Gender; Transgenders; Struggle for Existence; Marginalization Living Smile Vidya also known as in documentaries “Aghrinaigal” and smiley is an Indian trans-woman, actress, “Butterfly”. -

Public Bicycle Sharing System

ARAVANIS A FINAL PROJECT Submitted to Indian Institute of Technology Hyderabad IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF DEGREE of Master of Design Submitted By Safina Dhiman MD17MDES11010 Under the Guidance of Delwyn Jude Remedios Professor Department of Design DEPARTMENT OF DESIGN INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY HYDERABAD July 2019 DECLARATION I hereby certify that the Final Project entitled Aravanis, which is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of Master of Design is a record of my work carried out under the supervision and guidance of Delwyn Jude Remedios, Professor, Department of Design, Indian Institute of Technology Hyderabad. The matter presented in this Final Project has not been submitted elsewhere for the award of any other degree. Date: 1st July 2019 Place: Hyderabad Safina Dhiman MD17MDES11010 This is to certify that the above statement made by the candidate is correct to the best of my knowledge and belief. Guided by ………………………. Delwyn Jude Remedios Professor Department of Design Approved by ………………….. Dr. Neelkanthan Thesis Coordinator Department of Design ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to extend my gratitude to the following individuals for helping me complete this project by offering their valuable suggestions and for inspiring me without which this film would not have completed. 1. Prof. Deepak John Mathew, H.O.D (Department of Design) for his positive feedback. 2. My guide Delwyn Remedios for his valuable inputs, inspiration, and encouragement. 3. Sophia David for sharing her story and believing in me. 4. Sumit Saha and TJ Kartha for the music and voice-over. 5. -

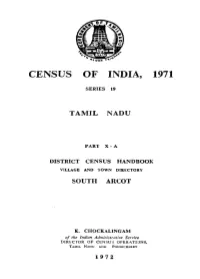

District Census Handbook, South Arcot, Part X-A, Series-19

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1971 SERIES 19 TAMIL NADU PART X - A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK VILLAGE AND 'lOWN DIRECTORY SOUTII AReOT K. CHOCKALINGAM of the Indian Administrative Service DIRECTOR OF CENSU~ OPERATION~ TAMIL NADU AND PONDICHERRY 1972 78 31 79r SOUTH ARCOT DISTRICT SCALE 5 0 5 10 15 Milll ~ AI NORTH AReOT Kllom.tr.,5 0 10 20 REFERENCB (Area: IO,ij8,OO I~, Kms,) Dlimet Heaaquarters , Taluk Headquarters @ f State Boundary I Diltnct Boundary I , Taluk Boundary ~ 'I National Highwayt , \ ~ State Highway! Il b Roads ~ Railway line (Metre Gauge) DHARMAPURI River with Stream Urban Areas Villages bavrng Population above llIOO Weekly Mark~s Post and Telegraph OffiCI PI Rest Houle, Travellen Bungalow Hospitals SALEM Nl.IIEO~m IREA IN NO, Of URBAN TlLIl( SQ KMS VillAGES W~lRES II Glnlel 1061,17 248 Nrl 'Ii TlndrvonDm 1!5·UI 199 I Vr/l~,urQm 910.75 118 I Trrukorlur 151l,11 Jj8 I KDIIDkurrchr 116l.Ol 311 I Vrrd~c/iQllIII 118l,19 281 1 Cud4Diore 1168.61 211 5 Chrdomborom 1045.11 lJ4 4 TIRUCHIRAPALLI THANIAVUR CONTENTS Page No. Preface V Part-A VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY Introductory Note VIl-XlI I. Village Directory Amenities and land use Appendix- 1 Land use particulars of Non-city urban area, (Non .. Municipal areJ) Appen dix-ll Abstract showing Educational, Medical and other amelllties available iD Taluks. Alphabetical list of villages. 1. GiDgee TaJuk 1- 32 2. Tindivanam TaJuk 33- 67 3 Villupuram Taluk 69- 94 4. Tirukoilur Taluk 9S-130 5 Kal1akurichi TaIuk 131-168 6. Vriddachalam Taluk 169-201 7. -

Religious Traditions in Modern South Asia

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:29 24 May 2016 Religious Traditions in Modern South Asia This book offers a fresh approach to the study of religion in modern South Asia. It uses a series of case studies to explore the development of religious ideas and practices, giving students an understanding of the social, politi- cal and historical context. It looks at some familiar themes in the study of religion, such as deity, authoritative texts, myth, worship, teacher traditions and caste, and some of the key ways in which Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam and Sikhism in South Asia have been shaped in the modern period. The book points to the diversity of ways of looking at religious traditions and considers the impact of gender and politics, and the way religion itself is variously understood. Jacqueline Suthren Hirst is Senior Lecturer in South Asian Studies at the University of Manchester, UK. Her publications include Sita’s Story and Śaṃkara’s Advaita Vedānta: A Way of Teaching. John Zavos is Senior Lecturer in South Asian Studies at the University of Manchester, UK. He is the author of The Emergence of Hindu Nationalism in India. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:29 24 May 2016 Religious Traditions in Modern South Asia Jacqueline Suthren Hirst and John Zavos Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:29 24 May 2016 First published 2011 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2011 Jacqueline Suthren Hirst and John Zavos The right of Jacqueline Suthren Hirst and John Zavos to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Download Issue

www.literaryendeavour.org ISSN 0976-299X LITERARY ENDEAVOUR International Refereed / Peer-Reviewed Journal of English Language, Literature and Criticism UGC Approved Under Arts and Humanities Journal No. 44728 VOL. X NO. 1 JANUARY 2019 Chief Editor Dr. Ramesh Chougule Registered with the Registrar of Newspaper of India vide MAHENG/2010/35012 ISSN 0976-299X ISSN 0976-299X www.literaryendeavour.org LITERARY ENDEAVOUR UGC Approved Under Arts and Humanities Journal No. 44728 INDEXED IN GOOGLE SCHOLAR EBSCO PUBLISHING Owned, Printed and published by Sou. Bhagyashri Ramesh Chougule, At. Laxmi Niwas, House No. 26/1388, Behind N. P. School No. 18, Bhanunagar, Osmanabad, Maharashtra – 413501, India. LITERARY ENDEAVOUR ISSN 0976-299X A Quarterly International Refereed Journal of English Language, Literature and Criticism UGC Approved Under Arts and Humanities Journal No. 44728 VOL. X : NO. 1 : JANUARY, 2019 Editorial Board Editorial... Editor-in-Chief Writing in English literature is a global phenomenon. It represents Dr. Ramesh Chougule ideologies and cultures of the particular region. Different forms of literature Associate Professor & Head, Department of English, like drama, poetry, novel, non-fiction, short story etc. are used to express Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, Sub-Campus, Osmanabad, Maharashtra, India one's impressions and experiences about the socio-politico-religio-cultural Co-Editor and economic happenings of the regions. The World War II brings vital Dr. S. Valliammai changes in the outlook of authors in the world. Nietzsche's declaration of Department of English, death of God and the appearance of writers like Edward Said, Michele Alagappa University, Karaikudi, TN, India Foucault, Homi Bhabha, and Derrida bring changes in the exact function of Members literature in moulding the human life. -

Villupuram Sl.No

VILLUPURAM SL.NO. APPLICATION NO. NAME AND ADDRESS R.DEVI W/O CHINNADURAI 1 4266 16,KUPPANOOR PILPARUTHI POST, PAPPIREDDIPATTI TAULK, DHARMAPURI 635301 K.R.MURUGAN S/O K.RAMAN 2 4267 228,M.G.R NAGAR, KUMARASAMYPATTAI PO, DHARMAPURI 636703 A.SELVAKUMAR S/O ARUMUGAM 369-A,VKS LAKSHMI NAGAR, 3 4268 OPP TO TNHB, EAST PONDY ROAD, VILLUPURAM 605602 M.MATHIAZHAGAN S/ O P.MURUGESAN 2/837-A, NELLI NAGAR, 4 4269 PIDAMANERI, OPP:RAILWAY STATION, DHARMAPURI 635302 T.S.JAYAMOHAN S/O M.T.SAMPATH 16,RAJAGOPALPILLAI ST, 5 4270 NAGALAPURAM, TINDIVANAM TK, VILLUPURAM 604002 A.MOHAN S/O ANNAMALAI, 6 4271 JAMMANAHALLI PO, HARUR TK, DHARMAPURI 635904 D.DHATCHANAMOOR THY S/O S.DESINGU MARIAMMAN KOIL ST, 7 4272 THURUVAI, RAYAPUTHUPAKKAM PO, VANUR TK, VILLUPURAM 605111 Page 1 N.VELMURUGAN S/O S.NATESAN 8 4273 PUGAIPATTI PO, ULUNMDURPET TK, VILLUPURAM 607202 S.KANNAN S/O SUBRAMANIYAN 9 4274 3,BALAKRISHNA ST, PONDY ROAD, VILLUPURAM 605602 G.SUBRAMANIYAN S/O GOVINDASAMY 10 4275 MUTHU GOUNDAN KOTTAI, OLD DHARMAPURI [PO], DHARMAPURI 636703 R.BALAMURUGAN S/O B.RAJAGOPAL D.NO.1-490, 11 4276 PAGALAHALLI[PO], NALLAMPALLI[VIA], DHARMAPURI 636807 T.PACHAMUTHU S/O G.THANGARASU ELAVATHADI, 12 4277 MUDAPALLI - PO, ULUNDURPET-TK, VILLUPURAM 607805 M.KANNAN S/O M.MUNIYAN 13 4278 THANDALAI & PO, SANKARAPURAM TK, VILLUPURAM MOORTHY. R 7/A, POUND STREET, 14 4279 MARANDAHALLI POST, PALACODE TALUK, DHARMAPURI J.SYEDAMEER S/O G.J AFFAR 15 4280 SATHYAMANGALAM & PO, GINGEE TK, VILLUPURAM 604153 G.KANNAN S/O.A.GOVINDARAJAN 16 4281 133,POOTTAI ROAD, SANKARAPURAM TK, VILLUPURAM 606401 Page 2 M.GEORGE ALBEN S/O.JOSEPHNATHAN 17,METTU STREET, 17 4282 PORPALAMPATTU & PO, SANKARAPURAM TK, VILLUPURAM 605801 P.KARUNAKARAN S/O. -

The Transgender Question in India: Policy and Budgetary Priorities

About Praxis Praxis - Institute for Participatory Practices is an NGO specializing in participatory approaches to sustainable development which aims to enable excluded people to have an active and influential say in equitable and sustainable development. Praxis is committed to mainstreaming the voices of the poor and marginalized sections of society in the process of development. This stems from the belief that for development to be sustainable, the process must be truly participative. Praxis acknowledges that ‘participation’ is not a technical or a mechanical process that can be realized through the application of a set of static and universal tools and techniques, but rather a political process that requires challenging the existing power structure. Thus, for Praxis, the community is not seen as an object but rather as an agent of change. It endeavours to work towards participatory democracy through social inclusion, public accountability and good governance. The primary focus is democratization of development processes. Copyright © UN Women 2014 Published in India The opinions expressed in this briefing paper do not necessarily represent those of UN Women, United Nations, or any of its affiliated organizations. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized, without prior written permission, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Authors: M.J. Joseph and Tom Thomas Compiled by: Ajita P. Vidyarthi Editorial inputs: Rebecca Reichmann Tavares, Yamini Mishra, Navanita Sinha and Bhumika Jhamb Designed by: Vidyun Sabhaney Printed by: Genesis Print, New Delhi Supported by: The transgender question in India: Policy and budgetary priorities The transgender (TG) community is one of the most marginalized social groups in the country.