Pre-And Post-Operational Effects of a Temperature Control Device On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantitative Approaches to Riparian Restoration in California (USA)

Quantitative Approaches to Riparian Restoration in California (USA) John C. Stella Dept. of Environmental Science, Policy and Management University of California, Berkeley and Stillwater Sciences [email protected] Restauración de Ríos Seminario Internacional Madrid, 20 Septiembre 2006 Outline 1. Riparian forests in California’s Mediterranean climate zone 2. Historical human impacts to the ecosystem 3. Deciding what to restore--processes or structure? 4. Quantitative approaches to restoring riparian forests -restoring ecological processes efficiently -restoring riparian structure effectively 1 Non-Equilibrium Ecosystems: Multiple Disturbances and Drivers of Change Fire Floods Climate change Landscape modification Sacramento River Length: 615 km Basin area: 70,000 km2) Sacramento River Basin San Joaquin River San Length: 530 km Francisco Basin area: 83,000 km2 Major tributaries: Tuolumne, Merced, Stanislaus Rivers Major California River Systems California Department of Water Resources. 2 Riparian Structure and Pattern Herbaceous cover Cottonwood forest Mixed riparian forest Valley oak forest • High structural complexity • Patchy distribution • Important terrestrial and in-stream habitat (litter, large woody debris, shade) Riparian Vegetation Establishment Processes on Alluvial Rivers RiverRiver channel channel TerraceTerrace FloodplainFloodplain PointPoint bar bar Channel Increasing age migration of vegetation Floodplain Terrace Eroding River Point bar (poplar/willow (valley oak bank channel (gravel & scrub) mixed forest) woodland) -

Shasta Lake Unit

Fishing The waters of Shasta Lake provide often congested on summer weekends. Packers Bay, Coee Creek excellent shing opportunities. Popular spots Antlers, and Hirz Bay are recommended alternatives during United States Department of Vicinity Map are located where the major rivers and periods of heavy use. Low water ramps are located at Agriculture Whiskeytown-Shasta-Trinity National Recreation Area streams empty into the lake. Fishing is Jones Valley, Sugarloaf, and Centimudi. Additional prohibited at boat ramps. launching facilities may be available at commercial Trinity Center marinas. Fees are required at all boat launching facilities. Scale: in miles Shasta Unit 0 5 10 Campground and Camping 3 Shasta Caverns Tour The caverns began forming over 250 8GO Information Whiskeytown-Shasta-Trinity 12 million years ago in the massive limestone of the Gray Rocks Trinity Unit There is a broad spectrum of camping facilities, ranging Trinity Gilman Road visible from Interstate 5. Shasta Caverns are located o the National Recreation Area Lake Lakehead Fenders from the primitive to the luxurious. At the upper end of Ferry Road Shasta Caverns / O’Brien exit #695. The caverns are privately the scale, there are 9 marinas and a number of resorts owned and tours are oered year round. For schedules and oering rental cabins, motel accommodations, and RV Shasta Unit information call (530) 238-2341. I-5 parks and campgrounds with electric hook-ups, swimming 106 pools, and showers. Additional information on Forest 105 O Highway Vehicles The Chappie-Shasta O Highway Vehicle Area is located just below the west side of Shasta Dam and is Service facilities and services oered at private resorts is Shasta Lake available at the Shasta Lake Ranger Station or on the web managed by the Bureau of Land Management. -

San Luis Unit Project History

San Luis Unit West San Joaquin Division Central Valley Project Robert Autobee Bureau of Reclamation Table of Contents The San Luis Unit .............................................................2 Project Location.........................................................2 Historic Setting .........................................................4 Project Authorization.....................................................7 Construction History .....................................................9 Post Construction History ................................................19 Settlement of the Project .................................................24 Uses of Project Water ...................................................25 1992 Crop Production Report/Westlands ....................................27 Conclusion............................................................28 Suggested Readings ...........................................................28 Index ......................................................................29 1 The West San Joaquin Division The San Luis Unit Approximately 300 miles, and 30 years, separate Shasta Dam in northern California from the San Luis Dam on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley. The Central Valley Project, launched in the 1930s, ascended toward its zenith in the 1960s a few miles outside of the town of Los Banos. There, one of the world's largest dams rose across one of California's smallest creeks. The American mantra of "bigger is better" captured the spirit of the times when the San Luis Unit -

2230 Pine St. Redding

We know why high quality care means so very much. Since 1944, Mercy Medical Center Redding has been privileged to serve area physicians and their patients. We dedicate our work to continuing the healing ministry of Jesus in far Northern California by offering services that meet the needs of the community. We do this while adhering to the highest standards of patient safety, clinical quality and gracious service. Together with our more than 1700 employees and almost 500 volunteers, we offer advanced care and technology in a beautiful setting overlooking the City. Mercy Medical Center Redding is recognized for offering high quality patient care, locally. Designation as Blue Distinction Centers means these facilities’ overall experience and aggregate data met objective criteria established in collaboration with expert clinicians’ and leading professional organizations’ recommendations. Individual outcomes may vary. To find out which services are covered under your policy at any facilities, please contact your health plan. Mercy Heart Center | Mercy Regional Cancer Center | Center for Hip & Knee Replacement Mercy Wound Healing & Hyperbaric Medicine Center | Area’s designated Trauma Center | Family Health Center | Maternity Services/Center Neonatal Intensive Care Unit | Shasta Senior Nutrition Programs | Golden Umbrella | Home Health and Hospice | Patient Services Centers (Lab Draw Stations) 2175 Rosaline Ave. Redding, CA 96001 | 530.225.6000 | www.mercy.org Mercy is part of the Catholic Healthcare West North State ministry. Sister facilities in the North State are St. Elizabeth Community Hospital in Red Bluff and Mercy Medical Center Mt. Shasta in Mt. Shasta Welcome to the www.packersbay.com Shasta Lake area Clear, crisp air, superb fi shing, friendly people, beautiful scenery – these are just a few of the words used to describe the Shasta Lake area. -

Shasta Dam Fish Passage Evaluation

Mission Statements The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian Tribes and our commitments to island communities. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Contents Contents Page Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................ 1-1 Project Background ........................................................................................ 1-3 Central Valley Salmon and Steelhead Recovery Plan ............................. 1-4 2009 NMFS Biological Opinion .............................................................. 1-5 Shasta Dam Fish Passage Evaluation ...................................................... 1-6 Purpose and Need .......................................................................................... 1-7 Objectives ...................................................................................................... 1-7 Study Area ..................................................................................................... 1-8 River Selection Process............................................................................ 1-9 Shasta Lake ............................................................................................ 1-10 Upper Sacramento River Watershed ..................................................... -

The Facts About Raising Shasta Dam

The Facts about Raising Shasta Dam May 10, 2019 Shasta Dam is the fourth highest dam in California1 and its 4.55 million acre-foot reservoir is the largest in the state.2 The dam captures water from three rivers (the upper Sacramento, McCloud, and Pit).3 Constructed and operated by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the Shasta Dam and Reservoir is the cornerstone of the giant Central Valley Project (CVP), which provides irrigation and drinking water for much of California’s Central Valley and parts of, and valleys just south of, the San Francisco Bay Area.4 In the Shasta Lake Water Resources Investigation (SLWRI) final Feasibility Report and Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS), the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation, USBR, or the Bureau) identified a plan with the greatest level of National Economic Development (NED) benefits as one including an 18.5-foot raise of Shasta Dam,5 which would increase water storage capabilities behind the dam by about 13%.6 This alternative, identified as the preferred alternative,7 was intended to improve conditions in the Sacramento River for threatened and endangered salmon and steelhead and increase the state’s overall water supply reliability.8 The Bureau released a final Feasibility Report and environmental impact statement (FEIS) which did not recommend any action (dam) alternative because of serious outstanding considerations,9 including: (1) The Bureau’s desire to have upfront funding from non-federal cost-sharing partners,10 (2) concerns by CVP contractors about CVP facilities serving non-CVP contractors,11 (3) California law prohibiting the expansion of Shasta Reservoir,12 (4) applicability of state environmental law to the project,13 and (5) process considerations. -

Sacramento River Temperature Task Group

Sacramento River Temperature Task Group Thursday, March 26, 2020 1:00 pm – 3:00 pm Conference Call Only: Join from PC, Mac, Linux, iOS or Android: https://meetings.ringcentral.com/j/5306224350 Or iPhone one-tap : US: +1(623)4049000,,5306224350# (US West) Or Telephone: Dial(for higher quality, dial a number based on your current location): US: +1(623)4049000 (US West) Meeting ID: 530 622 4350 International numbers available: https://meetings.ringcentral.com/teleconference Agenda 1. Introductions 2. Purpose and Objective 3. 2020 Meeting Logistics 4. Long Term Operations Implementation - Update 5. Hydrology Update 6. Operations Update and Forecasts a. Storage/Release Management Conditions b. Temperature Management 7. River Fish Monitoring: carcass surveys, redd counts, stranding and dewatering surveys and sampling at rotary screw traps 8. Fish Distribution/Forecasts: Estimated percentage of the population upstream of Red Bluff Diversion Dam for steelhead, winter-run and spring-run Chinook salmon, steelhead update and Livingston Stone Hatchery. 9. Seasonal Topics 10. Discussion 11. Review Action Items 12. Next Meeting Scheduling UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. BUREAU OF RECLAMATION-CENTRAL VALLEY PROJECT-CALIFORNIA DAILY CVP WATER SUPPLY REPORT MARCH 24, 2020 RUN DATE: March 25, 2020 RESERVOIR RELEASES IN CUBIC FEET/SECOND 15 YR RESERVOIR DAM WY 2019 WY 2020 MEDIAN TRINITY LEWISTON 318 303 303 SACRAMENTO KESWICK 10,188 4,569 3,798 FEATHER OROVILLE (SWP) 9,500 1,750 1,750 AMERICAN NIMBUS 4,887 1,516 1,516 STANISLAUS GOODWIN 4,504 206 428 SAN JOAQUIN FRIANT 2,987 0 286 STORAGE IN MAJOR RESERVOIRS IN THOUSANDS OF ACRE-FEET % OF 15 RESERVOIR CAPACITY 15 YR AVG WY 2019 WY 2020 YR AVG TRINITY 2,448 1,715 1,881 2,000 117 SHASTA 4,552 3,491 3,827 3,567 102 FOLSOM 977 602 681 466 77 NEW MELONES 2,420 1,562 2,025 1,892 121 FED. -

Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage Investigation Draft

Chapter 11 Geology and Soils This chapter describes the affected environment for geology and soils, as well as potential environmental consequences and associated mitigation measures, as they pertain to implementing the alternatives. This chapter presents information on the primary study area (area of project features, the Temperance Flat Reservoir Area, and Millerton Lake below RM 274). It also discusses the extended study area (San Joaquin River from Friant Dam to the Merced River, the San Joaquin River from the Merced River to the Delta, the Delta, and the CVP and SWP water service areas). Affected Environment This section describes the affected environment related to geology, geologic hazards, erosion and sedimentation, geomorphology, mineral resources, soils, and salts. Where appropriate, geology and soils characteristics are described in a regional context, including geologic provinces, physiographic regions, or other large-scale areas, with some area-specific geologic maps and descriptions of specific soil associations. Geology This section describes the geology of the primary and extended study areas. Primary Study Area A description of the surficial geologic units encountered in the primary study area is presented in Table 11-1. Geologic maps of the primary study area and the area of project features are presented in Figure 11-1 and Figure 11-2, respectively. Draft – August 2014 – 11-1 Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage Investigation Environmental Impact Statement Table 11-1. Description of Surficial Geologic Units of the Primary Study Area Geologic Map of Millerton Lake Quadrangle, West-Central Sierra Nevada, California1 Formation Surficial Deposits General Features Abbreviation Plutonic rocks characterized by undeformed blocky hornblende prisms as long as 1 cm and by biotite books as Tonalite of Blue Canyon much as 5 mm across. -

Choosing Our Vision for California's Water Future

LAS VIRGENES MUNICIPAL WATER DISTRICT 4232 Las Virgenes Road, Calabsas, CA 91302 AGENDA SPECIAL MEETING Members of the public wishing to address the Board of Directors are advised that a statement of Public Comment Protocols is available from the Clerk of the Board. Prior to speaking, each speaker is asked to review these protocols and MUST complete a speakers' card and hand it to the Clerk of the Board. Speakers will be recognized in the order cards are received. The Public Comments agenda item is presented to allow the public to address the Board on matters not on the agenda. The public may present comments on any agenda item at the time the item is called upon for discussion. Materials prepared by the District in connection with subject matter on the agenda are available for public inspection at 4232 Las Virgenes Road, Calabasas, CA 91302. Materials prepared by the District and distributed to the Board during this meeting are available for public inspection at the meeting or as soon thereafter as possible. Materials presented to the Board by the public will be maintained as part of the records of these proceedings and are available upon written request to the Clerk of the Board. 5:00 PM April 13, 2017 PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE 1 CALL TO ORDER AND ROLL CALL 2 APPROVAL OF AGENDA 3 PUBLIC COMMENTS Members of the public may now address the Board of Directors ON MATTERS NOT APPEARING ON THE AGENDA, but within the jurisdiction of the Board. No action shall be taken on any matter not appearing on the agenda unless authorized by 1 Subdivision (b) of Government Code Section 54954.2 4 CONSENT CALENDAR A List of Demands: April 13, 2017 (Pg. -

Trinity Dam Operating Criteria Trinity River Division Central Valley Project-California

·rRlNITY ~IVER BASIN us RESOURCE LIBRARY BR TRINITY COUNTY LIBRARY T7 WEAVERVILLE, CALIFORNIA 1979 (c.l) Trinity Dam Operating Criteria Trinity River Division Central Valley Project-California TRINITY COUNTY JULY 1979 TRINITY RIVER BASIN RESOURC E LIBRARY TRINITY RIVER DIVISION CENTRAL VALLEY PROJECT CALIFORNIA Trinity Dam Operating Criteria Prepared for the Trinity River Basin Fish and Wildlife Task Force July 1979 United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Mid-Pacific Region 1 ~ 7 5 122 R 1 W R 1 E 2 23° \ R 10 W ( T 38 N ----- ·-----]r------------r-CANADA ' I • I WA r NORTH ~ J SHINGTON ' \ ' DAKOTA ) ___ 1 • \.-.. ..-- .. J, ': M 0 N TAN A !___ - ----\ ' \ souTH : i ,----- - ~ ~~ ,o. 0 R EGON ( ,_---, : DAKOTA I : IOAHo 1 I __ __ \ \~' I W YOMING ·----- ~ -- -----, ___ , ,I \ ~ ~u I ~ 0 ; ------1 , NEBRASKA ', 1\ ~ I I ·--------'--, ~ I NEVA 1' 1: 0 ~1 : t------- -'.) I I J \_ DA UTAH COLORADO: ANSAS ' ~,J t -+- ---1--- .. - ', : : I K .\ ~ I . ---- .... ~ ' I 4!< l o ' ------·------ -- -~----- ', ~ -r' "::: rJ A ~ '!> ','\_r) i t---! OKLAHOMA\ -:- . I , , r/ / ;' ARIZONA I' NEW MEXICO. L ______ 1_ MALIN-ROUND MOUNTAIN 500 KV ~ . ' ,... 36 : , I l PACIFIC NW-PAC/FIC SW INTERTIE ---, ' ' ', I, ---~-E~~'-;:--·;;::<_-'r EX A_(S ---i- - ~ ~ - t \. .. _;··-....., ~ CLAIR ENGLE LAKE IN 0 EX M A P '._\_ ~.:.. (__j ~ ) I I / \ I - BUREAU OF RECLAMATION HASTAL~l WHISKEYTOWN-SHASTA( rr TRINITY [NAT . lj r COMPLETED OR AUTHORIZED WORKS 34 TRINITY DAM & POWERP~LANT~- ? ) RECrATION AREAS (~ ,- DAM AND RESERVOIR LEWISTON LAKE TRIINir/cARR 230 KV ? 0 I <=::? r ~-~~- _./ TUNNEL ~<";:1 r ~ -+ ---< - .r') d,):3_ -}N , ··- •J?:y,--.___ N CONDUIT - ~~ wcAv~~VIL' 7 __r~\. -

Oroville Dam Citizens Advisory Commission

OROVILLE DAM CITIZENS ADVISORY COMMISSION Hosted by the California Natural Resources Agency ITEM 1: WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS ITEM 2: NOVEMBER MEETING RECAP AND UPDATES ITEM 3: U.S. ARMY CORP OF ENGINEERS BRIEFING USACE ROLE IN NORTHERN CA FLOOD CONTROL OPERATIONS 237 217 200 80 252 237 217 200 119 174 237 217 200 27 .59 255 0 163 131 239 110 112 62 102 130 255 Oroville0 Dam163 Citizens132 Advisory65 Commission135 92 102 56 120 255 Southside0 163 Oroville122 Community53 Center120 56 130 48 111 Oroville, CA February 21, 2020 Joe Forbis, P.E. Chief, Water Management Section Sacramento District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers “The views, opinions and findings contained in this report are those of the authors(s) and should not be construed as an official Department of the Army position, policy or decision, unless so designated by other official documentation.” AGENDA • USACE Sacramento District Overview • Authorities, Roles, and Responsibilities • Water Control Manuals – Folsom Example • Pilot Project - FIRO Spillway Fuse Gates at Terminus Dam SOUTH PACIFIC DIVISION SACRAMENTO DISTRICT FC PROJECTS 8 SACRAMENTO DISTRICT (SPK) WATER MANAGEMENT USACE – 14 Section 7 – 31 Total – 45 SPK RESERVOIR EXAMPLES Largest Reservoir Shasta Dam and Lake 4,500,000 acre-feet Smallest Reservoir Mountain Dell Dam and Reservoir 3,200 acre-feet FLOOD OPS PARTNERS • Irrigation Districts – Stockton East Water District • Flood Control Districts – Fresno Metro Flood Control District • Federal Water Masters – Truckee River Basin Reservoirs • Water Storage Districts – Tulare Lakebed • Government Agencies – DWR – USBR Black Butte Dam USACE AUTHORITY FOR FLOOD OPS • Section 7 of the Flood Control Act of 1944 (58 Stat. -

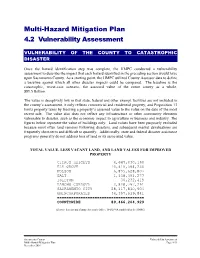

Section 4-2 Vulnerability3rdfinal

Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan 4.2 Vulnerability Assessment VULNERABILITY OF THE COUNTY TO CATASTROPHIC DISASTER Once the hazard identification step was complete, the HMPC conducted a vulnerability assessment to describe the impact that each hazard identified in the preceding section would have upon Sacramento County. As a starting point, the HMPC utilized County Assessor data to define a baseline against which all other disaster impacts could be compared. The baseline is the catastrophic, worst-case scenario, the assessed value of the entire county as a whole, $89.5 Billion. The value is deceptively low in that state, federal and other exempt facilities are not included in the county’s assessment, it only reflects commercial and residential property, and Proposition 13 limits property taxes by freezing a property’s assessed value to the value on the date of the most recent sale. The value also does not reflect any infrastructure or other community elements vulnerable to disaster, such as the economic impact to agriculture or business and industry. The figures below represent the value of buildings only. Land values have been purposely excluded because most often land remains following disasters, and subsequent market devaluations are frequently short-term and difficult to quantify. Additionally, state and federal disaster assistance programs generally do not address loss of land or its associated value. TOTAL VALUE, LESS VACANT LAND, AND LAND VALUES FOR IMPROVED PROPERTY CITRUS HEIGHTS 4,647,030,160 ELK GROVE 10,410,394,230 FOLSOM 6,895,628,807