Richmond's Archaeology of the African Diaspora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lake George Bateaux

THE LAKE GEORGE BATEAUX: BRITISH COLONIAL UTILITY CRAFT IN THE FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR A Thesis by NATHAN A. GALLAGHER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Chair of Committee, Donny L. Hamilton Committee Members, Kevin J. Crisman James C. Bradford Dead of Department, Cynthia Werner May 2015 Major Subject: Anthropology Copyright 2015 Nathan A. Gallagher ABSTRACT Bateaux were a key utility craft in military operations in the colonies of North America. Their size, durability, and ease of construction made them ideal for moving troops and supplies over the lakes and rivers of New York, New England and New France. General descriptions of bateaux are found in the historical record, but the archaeological record shows that they took several distinct forms between their advent in the late seventeenth century and the nineteenth century. This often causes confusion when bateaux are discussed by historians. This thesis provides a construction analysis of the remains of British colonial bateaux used during the French and Indian War. Comparison of these remains, which were recovered from Lake George and stored at the New York State Museum, provides a snapshot of British military bateau construction during the mid-eighteenth century. The examples and reconstruction of the Lake George bateaux presented in this paper show that the craft were built from a very simple design, but still required some expertise to achieve the level of craftsmanship in boatbuilding that is seen in the final result. Although these bateaux were hastily and lightly constructed, they were sturdy enough to survive the lakes and rivers they were expected to traverse. -

Some Notes on Shipbuilding and Shipping in Colonial Virginia

Some Notes On Shipbuilding and Shipping In Colonial Virginia By CERINDA W. EVANS Librarian Emeritus, The Mariners Museum Newport News, Virginia Virginia 350th Anniversary Celebration Corporation Williamsburg, Vir ginia 1957 COPYRIGHT©, 1957 BY THE MARINERS MUSEUM , NEWPORT NEWS, VIRGINIA Jamestown 350th Anniversary Historical Booklet, Number 22 AS CONCERNING SHIPS It is that which everyone knoweth and can say They are our Weapons They are our Armaments They are our Strength They are our Pleasures They are our Defence They are our Profit The Subject by them is made rich The Kingdom through them, strong The Prince in them is mighty In a word: By them in a manner we live The Kingdom is, the King reigneth. (From The Trades Increase, London, 1615) SHIPBUILDING AND SHIPPING THE DUGOUT CANOE Various types of watercraft used in Colonial Virginia have been mentioned in the records. The dugout canoe of the Indians was found by the settlers upon arrival, and was one of the chief means of transportation until the colony was firmly established. It is of great importance in the history of transportation from its use in pre-history to its use in the world today. From the dugout have come the piragua, Rose's tobacco boat, and the Chesapeake Bay canoe and bugeye as we see them today. The first boats in use by the colony in addition to the Indian canoe were ships' boats—barges, long-boats, and others. A shallop brought over in sections was fitted together and used in the first explorations. As the years went by, however, "almost every planter, great and small, had a boat of one kind or another. -

RIVERS, ENERGY, and the REMAKING of COLONIAL NEW ENGLAND by ZACHARY M

FLOWING POWER: RIVERS, ENERGY, AND THE REMAKING OF COLONIAL NEW ENGLAND By ZACHARY M. BENNETT A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of James Delbourgo And approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Flowing Power: Rivers, Energy, and the Remaking of Colonial New England by Zachary M. Bennett Dissertation Director: James Delbourgo This dissertation considers how river energy was a source of authority in colonial New England. The caloric, kinetic, and mechanical energy people derived from rivers was necessary for survival in New England’s forbidding environment. During the initial stages of colonization, both Europeans and Indians struggled to secure strategic positions on waterways because they were the only routes capable of accommodating trade from the coast to the interior. European and Native peoples came into conflict by the late seventeenth century as they overextended the resource base. Exerting dominion in the ensuing wars on New England’s frontiers was directly tied to securing strategic river spaces since the masters of these places determined the flow of communication and food for the surrounding territory. Following British military conquest, colonists aggressively dammed rivers to satisfy the energy demands of their growing population. These dams eviscerated fish runs, shunting access to waterpower away from Native Americans and yeoman farmers. The transformation of New England’s hydrology was a critical factor in the dispossession indigenous peoples before the Revolution and essential in laying the legal groundwork for the region’s industrial future. -

A Publication of the Virginia Canals and Navigations Society Summer 2007 Volume 28, Issue 2 2

The Tiller A Publication of the Virginia Canals and Navigations Society Summer 2007 Volume 28, Issue 2 2 2 The Tiller President Watercraft Operations Dan River Robert M. “Buddy” High William E. Turnage Bob Carter General Delivery 6301 Old Wrexham Pl. 1141 Irvin Farm Rd. Valentine, VA 23887 Chesterfield, VA 23832 Reedsville, NC 27320 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (434) 577-2427 Board of Trustees Eastern Virginia Vice-President Natalie Ross Kyle Schilling vacant PO Box 8224 30 Brook Crest Ln. Charlottesville, VA 22906 Stafford, VA 22554 Recording Secretary [email protected] (434) 577-2427 Jean High Term: 2007-2012 General Delivery Northern Virginia Valentine, VA 23887 Douglas MacLeod Myles “Mike” R. Howlett [email protected] PO Box 3119 6826 Rosemont Dr. Lynchburg, VA 24503 McLean, VA 22101 Corresponding Secretary [email protected] [email protected] Lynn Howlett Term: 2006-2011 6826 Rosemont Dr. Richmond William E. Trout, III, Ph.D. McLean, VA 22101 Vacant [email protected] 35 Towana Rd. Richmond, VA 23226 [email protected] Rivanna River Treasurer Term: 2005-2010 Peter C. Runge Atwill R. Melton 119 Harvest Dr. 1587 Larkin Mountain Rd. William E. Turnage Charlottesville, VA 22903 Amherst, VA 24521 See Watercraft Operations [email protected] [email protected] Term: 2004-2009 Southeast Virginia Archivist/Historian Richard Davis George Ramsey Phillip Eckman See VCNS Sales 2827 Windjammer Rd. 902 Park Ave. Term: 2003-2008 Colonial Heights, VA 23834 Suffolk, VA 23435 [email protected] [email protected] Webmaster District Directors Staunton River George Ramsey, Jr. Roy Barnard [email protected] Appomattox River 94 Batteau Rd. -

Rural Scenic Corridor Study

o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o Chapter VII-E Scenic Highways and Virginia Byways Roads are designated as scenic byways because of their unique, intrinsic qualities. …[to] invite the public to visit, experience, and appreciate… —Alan Yamada riving for pleasure has been ranked as one of Scenic Highway and Virginia Byway benefits the top five outdoor recreation activities for the Dpast 40 years. The appeal of scenic roads is the Scenic byways add economic benefits to the commu- intrinsic quality of Virginia’s diverse landscapes and nity. For example, the Blue Ridge Parkway, one of the the ease of connecting with nature from the automo- state’s three All-American Roads, adds more than bile. Traveling scenic byways provides an opportunity $945 million annually to Virginia’s economy. The to have a relaxing, comfortable outdoor experience Virginia Byway program also: that nourishes the need for a connection with nature. • Promotes adjacent communities and the scenic In fact, the 2006 Virginia Outdoors Survey (VOS) ranks byway corridor by including designated road seg- driving for pleasure as the third most popular outdoor ments on the state map for Scenic Roads of Virginia recreation activity. as well as information included on the Virginia Byways web site. There are both national and state sponsored scenic roads programs. The Virginia Byways program in • Creates an awareness of the unique qualities sur- Virginia recognizes natural, cultural, historical, recre- rounding scenic byways. -

Our R M Revolu Mosby Utiona Y Chil Ary W Lders Ar Gra Andfather

Mosby Childers Our Revolutionary War Grandfather By Barbara Couts Evans Dedicated to Bo Couts and Jack Childers For information, support, and inspiration and Benjamin Childers Jr. for his DNA A Special thanks to all those family and friends, who helped with names and a special thanks to LaVerne Parsons, Mrs. George F. Miller, Glen Walker, Lorilei K. Metke, Lee Rau, Kim Shumaker Clark, Virginia Hanks, the work of Mrs. Garnie Rooker, Steve Stevens and all of the other family genealogist of the Childers/Childress Family Association for sharing long hours of research. • Gary Childress, DNA; "Childers of early Virginia by Virginia Hanks" in attachments (Microsoft Word Document) • "Areas of land ownership, Childers by Virrginia Hanks" in attachments (Microsoft Word Document) • "Childers of early Virginia bby Virginia Hanks" in attachments (Microsoft Word Document) • "Areas of land ownership, Childers by Virrginia Hanks" in attachments (Microsoft Word Document) • • Childers of Early Virginia Henrico to Amherst records by year Prepared by Virginia Hanks , Ellenburg, Washington • Areas of Land Ownership, CHILDERS, Early Virginia Prepared by Virginia Hanks , Ellenburg, Washington • “PROGENITORS AND KINFOLK OF ABRAHAM CHILDERS III” By Alberta Marjorie Dennstedt • Wills, Deeds, Indentures, Childers/Childres,Childry, Childress Families Of Virginia 1656 - 1791 BBy Patricia Childress Spurlinng Mosby Childers ~ Our Revolutionary War Grandfather Mosby died on August 03,1843, in Hancock County, Indiana at the age of eighty-four (84) years. He was well remembered by his descendents in family lore for being a kind and gentle person, who told “wonderful” stories about his family members, the war, and his life. The grave of Mosby CHILDERS has not been definitively located. -

Benedict Arnold in Virginia

` “ HOSTAGE TO FORTUNE”: BENEDICT ARNOLD’S INVASION OF VIRGINIA IN 1781 Benedict Arnold has the unique and questionable distinction of being the only American who served as a general officer on opposing sides in the same war. His military record, as an officer on the American side from 1775 to 1780, was exceptional. He was instrumental in capturing the fort at Ticonderoga in May of 1775 and in saving Fort Stanwix in the Mohawk Valley in August of 1777. In the fall of 1775, he led a force of a thousand men on a three hundred mile march through the Maine wilderness to participate in a New Years Eve attack on Quebec. The next year he supervised the building of a fleet of boats and then used those boats effectively in a delaying action on Lake Champlain. In 1777, he fought in the Battle of Ridgefield and then played a pivotal role in defeating a British army at Saratoga. In September of 1780, his attempt to deliver the fortification at West Point to the British was discovered shortly after his first face to face meeting with the British, and he barely escaped to a British ship before being captured by the Americans. Arnold’s military career did not end with his escape to the British side. Even though there was mixed reaction among the British officers and loyalist leaders in New York, the British commander in chief, Sir Henry Clinton, made him a British brigadier general. Although Arnold had proven himself as an American military leader, he faced resistance because some in British controlled New York suspected his recent allegiance to the British cause and some blamed him for his role in the death of John Andre, who was a very popular aide to Clinton and had been the British contact in the negotiations with Arnold. -

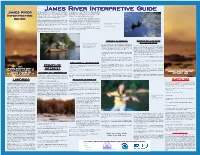

James Riv James River Interpretive Guide

JamesJames RivRiverer IntIntererprpreetivtivee GuideGuide to Robious Landing on river right; 5 miles to Bosher’s dam 9. At mile 20.5, on river right, is the Cartersville Boat James River portage, on river left. From the dam, it is 1 mile to Landing. The river gage is on river left. Also, there are Huguenot Flatwater Park, 2 miles to Pony Pasture Rapids stone piers of an early bridge that served wagons going Interpretive Park and 4½ miles to Reedy Creek, all on river right. The between Cumberland and Goochland counties. last take-out before Class 3 and up rapids. Guide 10. At mile 21, on river left, is the Cartersville Connection Guide Robious Landing Park is just behind James River High Lock. This lowered boats from the canal into the river so School, off Rt. 711, 3 miles from Rt. 150. This is a large they could dock at Cartersville. A short way down stream park with a slide launch that will accommodate canoes, is the Connection Dam that created slack water up to Fishing along the James River is a kayaks, and rowing shells. Both a picnic shelter and Cartersville for canal boats using the lock. popular activity. restrooms are available all year. Photo: David Euerette © 11. At mile 21.5, on river right, Muddy Creek marks the Huguenot Flatwater Park, on river right, (part of James boundary between Cumberland County to the west and River Park System) has canoe access steps. A portable Powhatan County to the east. toilet is available from mid-May to October. MAIDEN’S TO WATKINS WATKINS TO HUGUENOT Batteaus travel the James River FLATWATER PARK 24. -

Located in the Elizabeth River Ferry Docking Facility City .Of Portsmouth

Archaeologicdl Documentation of the Remains ofa Late Eighteenth- or Eddy Nineteenth-Centu y Kissel Located in the Elizabeth River Ferry Docking Facility City .of Portsmouth, Virginia A Technical Report Series No. 6 2006 Virginia Department of Historic Resources 280 1 Kensington Avenue Richmond, VA 23221 Archaeological Documentation of the Remains of a Late Eighteenth- or Early Nineteenth- Centuy Vessel Located in the Elizabeth River Ferry Docking Facility, City of Portsmouth, Virginia Technical Report Series No. 6 Virginia Department of Historic Resources Tidewater Regional Preservation Office 1441 5 Old Courthouse Way, 2nd Floor Newport News, VA 23608 PREPAREDFOR: Hampton Roads Transit P.O. Box 2096 Norfolk, VA 2350 1 PREPAREDRX Tidewater Atlantic Research, Inc. P. 0. Box 2494 Washington, North Carolina 27889 PROJECTD~RE~TOR: Gordon P. Watts, Jr. AUT~RS: Gordon Watts Roderick Mather Raymond Tubby During the excavation of a ferry docking facility on the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River in downtown Portsmouth, Virginia, the remains of a wooden vessel were discovered. Construction crews uncovered two sections of the vessel approximately 20-25 ft. below the gound surface. As construction of the ferry facility necessitated removal of the wreck, Ham- p ton Roads Transit contracted with Tidewater Atlantic Research, I nc. (TAR), of Washington, North Carolina, to develop a measured ~lanof the surviving vessel remains prior to their removal and document each significant element of the structure after removal. The archaeo- logical documentation carried out by TAR was designed to meet the provisions of Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended through 1992 (36 CFR 800, Protection of Historic Proper+ties) and the Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1987 (Abandoned Ship- wreck Act Guidelines, National Park Service, Federal Register, Vol. -

Historic Black Lives Matter: Archaeology As Activism in the 21St Century Kelley F

African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter Volume 15 Article 1 Issue 1 Spring 2015 Spring 2015 Historic Black Lives Matter: Archaeology as Activism in the 21st Century Kelley F. Deetz University of Virginia, [email protected] Ellen Chapman College of William & Mary, [email protected] Ana Edwards Sacred Ground Historical Reclamation Project of the Defenders for Freedom, Justice & Equality, [email protected] Phil Wilayto Virginia Defender, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/adan Part of the African American Studies Commons, African Languages and Societies Commons, American Art and Architecture Commons, American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, History Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Deetz, Kelley F.; Chapman, Ellen; Edwards, Ana; and Wilayto, Phil (2015) "Historic Black Lives Matter: Archaeology as Activism in the 21st Century," African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter: Vol. 15 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/adan/vol15/iss1/1 This Articles, Essays, and Reports is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Deetz et al.: Historic Black Lives Matter Historic Black Lives Matter: Archaeology as Activism -

THE KEYSTONE of PLANTATION WEALTH? CASE STUDIES (Under the Direction of Dr

ABSTRACT Theresa R. Hicks. WHARVES: THE KEYSTONE OF PLANTATION WEALTH? CASE STUDIES (under the direction of Dr. Lynn Harris) Department of History, April 11, 2012. The Bowling Farm Site (001CSR), a multi-component site comprising Native American and European artifact assemblages, a wharf structure, and a shipwreck, represents a unique clue to early North Carolina history. Located on the Cashie River in Bertie County, this site may be seminal to the history of colonial North Carolina settlement and economy, since little is known about colonial settlement in this area. The primary focus of this thesis is to explore the possibility of a potential correlation between the site’s economic history, wharf construction, and the artifact assemblage by comparing Bowling Farm Site to five other plantation wharf sites located in Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. This thesis also aims to promote the importance of archaeology in understanding site history and formation processes on wharf sites while exploring the most appropriate archaeological methodologies to achieve this objective. WHARVES: THE KEYSTONE OF PLANTATION WEALTH? CASE STUDIES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Arts in History by Theresa R. Hicks April 2012 © copyright Theresa R. Hicks WHARVES: THE KEYSTONE OF PLANTATION WEALTH? CASE STUDIES by Theresa R. Hicks APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF THESIS _________________________________________________________ Lynn Harris, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER ________________________________________________________ Bradley Rodgers, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER ________________________________________________________ Carl Swanson, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER ________________________________________________________ Tony Boudreaux, Ph.D. CHAIR OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY _____________________________________ Gerald J. -

An Assessment of Virginia's Underwater Cultural Resources

AN ASSESSMENT OF VIRGINIA'S UNDERWATER CULTURAL RESOURCES Virginia Department of Historic Resources Survey and Planning Report Series No. 3 The College Of WILLI.AM&W AN ASSESSMENT OF VIRGINIA'S UNDERWATERWAER CULTURAL RESOURCES Virginia Department of Historic Resources Survey and Planning Report Series No. 3 Prepared by: William and Mary Center for Archaeological Research Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary Williamsburg , Virginia 23 187 Project Directors Dennis B. Blanton Donald W. Linebaugh Authors Dennis B. Blanton Samuel G. Margolin This cultural resources assessment was funded, in part, by the Department of Environmental Quality's Coastal Resources Management Program through Grant #NA370Z0360-01 of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA or any of its subagencies. An Assessment of Virginia's Underwater Cultural Resources (1994) is firnded in pan by a grant from the National Park Service, U. S. Dept. of the Interior. Under litle M of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U. S. Dept. of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin or handicap in its federally assisted programs.ifyou believe you have been discriminated against in any program or activity or facility described above, or if you desire firzher information, please write to: OBce for Equal Opponunity, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Washington,D.