Heliotrope #1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twisted Tongue Magazine

Short Stories Twisted Tongue Magazine Bugged – Matt Plass 2 Unbelievable – Brandon Sewell 14 Issue 8 Questions (A Personal Hell) – Nik Perring 17 The Last Good Captain – Joshua Allen 25 Blood Ties – S H Hughes 28 Welcome to Twisted Tongue issue eight. Packed with thousands Split Infinities – Rod Hamon 31 of words—larger than a standard novel—over 100,000 words. The Carol Singers – Peter Tennant 37 There should be something in this issue for everyone … if Board of Life – David Elliott 39 not, then let us know. Twisted Tongue is a magazine unlike any A Texas Story – Jesus Moya 42 other … here you will find works that are twisted and we don’t Heart and Soul of the Western Warrior – Tyler Keevil 43 mean ones with a simple twist. This magazine is for those 18 and Twist – William D Hicks 47 over. Ghost Wanted – Ted Stetson 53 Vincent’s and Miki’s Dreams – Gene Hines 55 In this issue, you’ll read some Christmas tales to chill you Kings and Queens – Paul L Mathews 60 with twisted Santa Claus’s, a disturbed Rudolph, creepy Carol Naked Physics – Kelly Jameson 68 singers and evil toys. And for those who can’t stand Christmas Holding On – Ken Elkes 72 we have a selection of Twisted Tongue’s spectacular regular Midnight at the Highcliff Rest – Drue Fairlie 74 pieces to thrill you. My Ugly Little Self – Lou Antonelli 76 This issue I’ve chose Shaun Hamilton’s short story You’d All the Young Dudes (And One Hippie Princess) – J Michael Shell 79 Better Watch Out as Ed’s Choice. -

Another Girl, Another Planet Online

midM1 (Free download) Another Girl, Another Planet Online [midM1.ebook] Another Girl, Another Planet Pdf Free Lou Antonelli ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #649727 in eBooks 2017-01-29 2017-01-29File Name: B01MUG3V83 | File size: 43.Mb Lou Antonelli : Another Girl, Another Planet before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Another Girl, Another Planet: 3 of 3 people found the following review helpful. Buy this book! It's lots of fun!By brendan f kellyReally fun book. Reminds me a lot of the early Heinlein stories. Part thriller, part mystery, part space opera it was the best read I've had in a long time. The universe it is set in is incredibly compelling (despite a nit pick or two), and it is a TREMENDOUSLY fun read. I was actually late to my doctor appointment because I literally could not put it down. I'm really hopeful there will be a sequel because I really enjoyed it.I gave it four stars because there are a couple of spots that I found a little unbelievable (in regards to characters not plot). That being said, when Mr. Antonelli is on, he is ON. There are some action sequences that are really great, and some of sad parts are really moving. Well worth the money, definitely a fun, interesting, and compelling read.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Secret history on Mars debut novel!By Margaret A. DavisSecret history wrapped in alternate history. -

Vol. 3 No. 10 Oct. 1994

Complimentary to churches and community groups pinorittj ©Mortunitij Jleui^ VOLUME 3. NO. 10 2730 STEMMONS FRWY. STE. 1202 TOWER WEST, DALLAS, TEXAS 75207 OCT. 1994 The Texas Special Electio Publishers Profile Association take a of • The Races stand on the state's Senator Royce West • The Candidates Governors Race • The Issues From the Publisher In mm Thurman Jones Unsung Hero of the Month sheriff's or other law enforcement agen addition, residents of the Apartment cies for help. The company will desig Association of Greater Dallas collected .._.,.,..„„__^~ ...„__^ Southwestern nate more than 1,5(X) vehicles as Mcgruff loose coins at tlteir property office. trucks through out its service area. Thanks for Bell telephone For more information call Pam has nominated Quitty (214) 830-2661. your support Opral Nelson as the unsung If you tuned in to our August and hero of the September issues, you are well aware month because Communittf housing fund of Minority Opportunity News' recent of her dedica crusade to delay the proposed transfer tion to all eth Housing available for low-income of licenses from Summilt nic minority buyersComnxunity Housing Fund, a Communications, which currently Opral Nolson entrepreneur, non-profit organization formed to owns KJMZ/100.3 FM and getting the assist low*to-moderate income first- Introducing itie new program at Jose Navarro time home KHVN/Heaven 97 AM, to New York- information necessaty to do business PK-3 Elementary School are, from teft: Dallas buyers, ; • -- -——•'«—-^^•••--- —- based Granum Communications, Inc. with SWBT. Also, she will go the extra City Councitwomen barbara Mallory; Chrystal broke ^^ (GCI), After a direct appeal, the Federal miles to ensure that you get the oppor ShiGid, student; Mcgnjff iho Crime Dog; Sonny ground on J'^ "^ Communications Commission (FCC) tunity to be included in the pipeline Vasquez, student; Steve Bell, Dallas police olli- a new IV'' graciously honored our request to whenever the opportunity arrives. -

Pocket Program

LoneStarCon 3 POCKET PROGRAM The 71st Worldcon August 29–September 2, 2013 San Antonio, Texas The Dedication Nin Soong Fong Who gave me heart and soul Elizabeth “Liz” Metcalfe Whose heart never really left Texas Wayne Fong Together we steered Starships: Qapla’ Some of these conversations are for you I miss y’all - Terry Fong “World Science Fiction Society,” “WSFS,” “World Science Fiction Convention,” “Worldcon,” “NASFiC,” “Hugo Award” and the distinctive design of the Hugo Award Rocket are service marks of the World Science Fiction Society, an unincorporated literary society. “LoneStarCon 3” is a service mark of ALAMO, Inc., a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation, registered in Texas. Getting Started Welcome To loneSTarcon 3! There and back again....or deja’ vu all over again. For years, Bill and Randy’s modus operandi at a Worldcon With apologies to J. R. R. Tolkien and Yogi Berra. This journey, was to be up early for breakfast to be sure they made the like many great adventures, began in a bar (or behind one first panel of the day (and yes, starting at 9 or 10 in the anyway). Back in the early 1990s when the bid was underway morning there is always a cool program item...so go take for LoneStarCon 2, we both volunteered to help with the bid. your pick!). A day of constant activity moving back and forth GETTING STARTED In those early days that entailed table sitting (one of fandom’s between art show, dealers’ room, exhibits, and multiple thankless jobs), door greeter at the parties, and quite often panels, then shifting to evening events and finally parties. -

Asfacts Apr15.Pub

ASFACTS 2015 APRIL “V ARIED WEATHER ” S PRING ISSUE Winners will be announced at the Nebula Awards Ban- quet June 6 at the Palmer House Hilton, Chicago IL. In addition to his contributions to the genre, Niven has influenced the “fields of space exploration and technology.” The Grandmaster Award is given for “lifetime achievement VERNON AMONG 2014 N EBULA NOMINEES ; in science fiction and/or fantasy.” Jeffry Dwight will receive the 2015 Kevin O’Donnell Jr. Service to SFWA Award. NIVEN NAMED SFWA G RAND MASTER In late February, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writ- 2015 H UGO AWARD FINALISTS ANNOUNCED ers of America released the final ballot for the 2014 Nebula Awards. The group also named Larry Niven the recipient of The finalists for the 2015 Hugo Awards were announced the Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award, citing his April 4 at Norwescon and three other conventions and online “invaluable contributions to the field of science fiction and via UStream, as well as via the Twitter feed and other social fantasy.” A full list of nominees, including Bubonicon 44 media of Sasquan, the 2015 Worldcon. Artist Guest Ursula Vernon, follows: Since then, the Hugo committee has decided that two Novel: The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison, nominees were not eligible, two other nominees have asked Trial by Fire by Charles E. Gannon, Ancillary Sword by Ann for their names to be removed from the ballot, and Connie Leckie, The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu, Coming Willis has withdrawn as an award presenter at the ceremony Home by Jack McDevitt, and Annihilation by Jeff Vander- – all due to controversy around the nominees. -

February 4-6

Volume 1, Issue 22 June 2011 2 Editorial: Well, that seemed like a fast month! Maybe it was that I was a week late with the zine last time around. Even still, y’all managed to load us down with some good letters of comment. The calendar is as packed as ever – summer’s a good season for cons in the South. I kicked off my summer last weekend with a trip up to Balticon (my first time there) and enjoyed myself immensely. As we’ve established that for the purposes of this zine, Baltimore is in the South, I’d say that was starting it off right. Balticon had a great mixture of young and old fans, which felt similar to Chattacon. On the way home, Glug and I discovered that Waffle House now offers sausage gravy as a hash brown topping, which led to the realization that we can make Southern-style poutine out of Waffle House hash browns. Look for more on that next ish. I’m continuing my slog through the Hugo fiction, and this ish, we get through the short stories, novelettes, and another of the novels, plus Glug gives us a look at the graphic stories. Finally, we’ll be closing out with another great article from Dr. Jeff! Enjoy, y’all. Contents: Calendar of Events 3 Rebel Yells (Y’all) 11 Reviews: The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms 19 Hugo Short Stories 20 Hugo Novelettes 21 Hugo Graphic Stories (Christopher Hensley) 22 Memories of Fanex Past: 1996-2001 (Dr. Jeff Thompson) 25 Art Credits: Jose Sanchez – cover, page 25 Brad Foster – Renovation logo on page 7 Mike Moon – page 21 FenCon logo copyright the Dallas Future Society Colophon: Editor & SFC President: Warren Buff [email protected] (919) 633-4993 8712 Wellsley Way Raleigh, NC 27613 USA All contents copyright their creators. -

September 2007 the Next NASFA Meeting Is the Cookout on 15 September 2007 at Marie & Mikeõs House See the Announcements Below for Concom Dates

The SHUTTLE September 2007 The Next NASFA Meeting is the Cookout on 15 September 2007 at Marie & MikeÕs House See the Announcements Below for Concom Dates { { 09 BD: Mike Cothran. Oyez, Oyez 09 GrandparentsÕ Day. 11 Patriot Day. The next NASFA meeting, on Saturday 15 September 11 BD: Ray Pietruszka. 2007, will be the more-or-less annual NASFA Cookout, held 12 BD: Pat Butler. this year at Marie McCormack and Mike CothranÕs house Ñ 13 Rosh Hashanah. 210 Vincent Road SE in Huntsville. The eating and socializ- 14Ð16 Hub Con XV Ñ Hattisburg MS. ing will begin around 1P and go until Mike and Marie kick us 15* NASFA Cookout/Picnic (Replaces Meeting) Ñ 1P out. Bring what you want to drink and food to share. There at Mike and MarieÕs house. should be a grill available so bring something to throw on it Ñ 15 Games Day Memphis Ñ Memphis TN. coordinate with Mike at 256-880-8210. Help setting up before 17 Citizenship Day. the cookout (possibly as early as 10A) would be appreciated; 20 Concom Meeting (Marie and MikeÕs house). again call 256-880-8210 to coordinate. 21Ð23 Anime Weekend Atlanta 13 Ñ Atlanta GA. The next Con Stellation concom meeting will be at 7P, 22 Yom Kippur. Thursday 20 September 2007, also at M&MÕs house. There 23 Fall begins. will likely be another meeting two weeks after that, on 4 26 BD: Jenna Victoria Stone. October 2007. Watch your email for any additional details. 26 Movie at the Main Library (6P): Blade Runner (1982). -

Lonestarcon 3, the 71St Worldcon, to Be Held August 29-September 2,2013, in San Antonio, Texas Lonestarcon 3

PROGRESS REPORT 3 The third Progress Report for LoneStarCon 3, the 71st WorldCon, to be held August 29-September 2,2013, in San Antonio, Texas LoneStarCon 3 j a d er 2013 Welcome to the New Frontier A bid for the 73rd World Science Fiction Convention Spokane, Washington August 19-23, 2015 Let's bring the Worldcon to the Northwest! We want to share with the rest of the world • a huge active local and regional communities of fans, authors, artists, filkers, costumers, gamers, otaku, and more creative folks • at a 21st century facility with a Broadway-quality theater for events • in the heart of a beautiful, thriving city with hundreds of restaurants and cultural and outdoor activities (with perfect weather in August). Find out more at spokanein2015.org. The Spokane in 2015 Worldcon Bid is a project of SWOC. The Holidays ate Over, the presents have all been put away the last sweet treat has been enjoyed and it’s less than nine months before another momentous event when San Antonio hosts its second Worldcon. It's time to make your hotel reservations for your stay in San Antonio, deliberate which great works to nominate for the Hugo Awards, and learn more about where Worldcon will be held in 2015 and the NASFiC in 2014. San Antonio is an exciting destination that you might want to learn more about as well. This is our largest Progress Report. We have articles on several of our Guests of Honor and a few peeks at the exciting items we are planning for exhibits, programming and events. -

July 2013 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle July 2013 Te Next NASFA Meetng is Saturday 20 July 2013 at te Regular Locaton ConCom Meeting 20 July 2013; ConCom Meetings now twice a month; see page 2 for details JULY ATMM d Oyez, Oyez d The July After-The-Meeting Meeting will be at Dunkin’ Do- nuts—1221B Memorial Parkway NW in front of Costco. The next NASFA Meeting will be Saturday 20 July 2013 They’re open until 10P and, if the weather is nice, they have an at the regular meeting location—the Madison campus of Wil- outdoor seating area between them and the Five Guys Burgers lowbrook Baptist Church (old Wilson Lumber Company build- and Fries next door. ing) at 7105 Highway 72W (aka University Drive). Please see the map at right if you need help finding it. PLEASE NOTE that the meeting will start at 5:30P (30 minutes earlier than usual) so we can leave the church in time Road Jeff Kroger to make it to the program. JULY PROGRAM The July program will be at the Von Braun Astronomical US 72W Society Planetarium <www.vbas.org/index.php/planetarium>: (aka University Drive) “Life in the Universe” with Gena Crook. The program starts at 7:30P, but we need to get there 7-ish to make our way in and get settled. NASFA will pay for VBAS entry (though donations are wel- Road Slaughter come). Please contact Judy or Sue <nasfa.programming@ Map To con-stellation.org> if you plan to attend so we can get an ap- Meeting Parking proximate headcount. -

Auroran Lights

AURORAN LIGHTS The Official E-zine of the Canadian Science Fiction & Fantasy Association Dedicated to Promoting the Prix Aurora Awards and the Canadian SF&F Genre (Issue # 17 – July 2015) 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 – EDITORIAL CSFFA SECTION 05 – How to Join CSFFA (so you can vote for the Aurora Awards). 05 – How to download Voter’s Package of nominated works for you to read. 05 – How to vote for the Aurora Awards. 06 – CSFFA deadlines timeline. 06 – Canvention 35 reminder. PRODOM SECTION 08 – MILESTONES – New Comic shop in Edmonton, Edge announces new imprint, Melissa Mary Duncan art show, I Love You Judy Merril! & Leacock Summer Festival. 08 – AWARDS – 2015 Aurora Award Ballot Nominees (Pro), BC Book Prize finalist, Hugo nominees, Philip K. Dick Award, BSFA Awards, Ditmar Awards. 13 – CONTESTS – Friends of the Merril short story contest winners, Gernsback SF Short story Contest, Writers Trust of Canada Retreat program. 14 – EVENTS – Robert Charles Wilson Book Signing, Bundoran Press appearances, On Spec Magazine appearances. 15 – POETS & POEMS – Morrigan’s Song by Colleen Anderson, The Cry of the Autumn Stars by Matt Fuller Dillon, 2015 Ryhsling poetry Awards. 15 – PRO DOINGS – Robert Charles Wilson, Robert J. Sawyer, Ron Friedman, Lynda Williams, Matthew Hughes, Randy McCharles, & Robert Runté. 10 – CURRENT BOOKS & STORIES – Signal to Noise by Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Death’s Door by William DeSouza, The Affinities by Robert Charles Wilson, Faces by E.C. Blake (Edward Willett), Two- Year Man by Kelly Robson. 12 – UPCOMING BOOKS & STORIES – We Stand on Guard by Brian K. Vaughn & Steve Skroce, The Cave Beneath the Sea by Edward Willett, A Holo for Ameris by Jade Brienne, Torrent of Tears by Jenny Madore, Spit Test by Jennifer Lott, The Playground of Lost Toys edited by Collen Anderson & Ursula Pflug, nEvermore! Tales of Murder, Mystery, and the Macabre edited by Nancy Kilpatrick and Caro Soles, Professor Challenger: New Worlds, Lost Places edited by J.R. -

Tightbeam 309 June 2020

Tightbeam 309 June 2020 Lady Mage — Magic Moon By Angela K. Scott Tightbeam 309 June 2020 The Editors are: George Phillies [email protected] 48 Hancock Hill Drive, Worcester, MA 01609. Jon Swartz [email protected] Art Editors are Angela K. Scott, Jose Sanchez, and Cedar Sanderson. Anime Reviews are courtesy Jessi Silver and her site www.s1e1.com. Ms. Silver writes of her site “S1E1 is primarily an outlet for views and reviews on Japanese animated media, and occasionally video games and other entertainment.” Regular contributors include Declan Finn, Jim McCoy, Pat Patterson, Tamara Wilhite, Chris Nuttall, Tom Feller, and Heath Row. Declan Finn’s web page de- clanfinn.com covers his books, reviews, writing, and more. Jim McCoy’s reviews and more appear at jimbossffreviews.blogspot.com. Pat Patterson’s reviews ap- pear on his blog habakkuk21.blogspot.com and also on Good Reads and Ama- zon.com. Tamara Wilhite’s other essays appear on Liberty Island (libertyislandmag.com). Chris Nuttall’s essays and writings are seen at chrishang- er.wordpress.com and at superversivesf.com. Samuel Lubell originally published his reviews in The WSFA Journal. Some contributors have Amazon links for books they review, to be found with the review on the web; use them and they get a reward from Amazon. Regular short fiction reviewers Greg Hullender and Eric Wong publish at RocketStackRank.com. Cedar Sanderson’s reviews and other interesting articles appear on her site www.cedarwrites.wordpress.com/ and its culinary extension. Tightbeam is published approximately monthly by the National Fantasy Fan Federation and distributed electronically to the membership. -

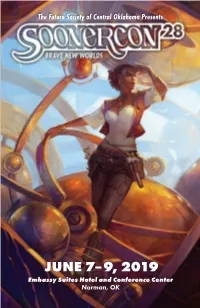

June 7–9, 2019

The Future Society of Central Oklahoma Presents SOONERCON 28 JUNE 7–9, 2019 7–9, JUNE JUNE 26–28, 2020 EMBASSY SUITES HOTEL & CONFERENCE CENTER | NORMAN, OK JUNE 7– 9, 2019 Embassy Suites Hotel and Conference Center GET YOUR EARLY BIRD MEMBERSHIP Norman, OK AT CONVENTION REGISTRATION. TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Chair ........4 Artist Guest of Honor .... 27 A Note from FSCOK .........5 Writers Workshop Clinician ......................... 29 SoonerCon 28 Sponsors ..6 Toastmaster .................... 31 Convention Committee .....7 Featured Guests ..............33 Letter from Positive Tomorrows ........................9 The Art of Julie Dillon .... 48 SoonerCon Policies ........11 SoonerCon 27 Winners .53 Special Thanks ................16 Program Summaries Friday ......................... 55 Friends of SoonerCon ....17 Saturday .................... 67 Facility Map ....................18 Sunday ....................... 79 Program Highlights .........21 Guest Bios ...................... 87 Literary Guest of Honor .25 Final Salute ...................120 Cover illustration by Julie Dillon. Book design by Phillip Grimes. Edited by Mark Alfred, Matthew Alfred, Aislinn Burrows, Amber Hanneken, Damon Seymour, Shai Fenwick, and Leonard Bishop. The SoonerCon Program Book, Volume 14, Number 1, is published annually by the Future Society of Central Oklahoma (FSCOK). Copyright © 2019 FSCOK. After publication in this form, all rights return to individual authors and artists. Nothing in this Program Book may be reproduced without the permission of FSCOK and/or the individual artist or author. All copyrighted images remain the property of their prospective owners. FROM THE CHAIR e call it bravery when someone perseveres, despite their fear, to endure the challenges before them. It sounds easy, but it’s one of the most difficult things to be: Brave. ScienceW fiction’s narratives and its imagined technologies envision a brave creative space.