Pop Music, Culture and Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BWTB Nov. 13Th Dukes 2016

1 Playlist Nov. 13th 2016 LIVE! From DUKES in Malibu 9AM / OPEN Three hours non stop uninterrupted Music from JPG&R…as we broadcast LIVE from DUKES in Malibu…. John Lennon – Steel and Glass - Walls And Bridges ‘74 Much like “How Do You Sleep” three years earlier, this is another blistering Lennon track that sets its sights on Allen Klein (who had contributed lyrics to “How Do You Sleep” those few years before). The Beatles - Revolution 1 - The Beatles 2 The first song recorded during the sessions for the “White Album.” At the time of its recording, this slower version was the only version of John Lennon’s “Revolution,” and it carried that titled without a “1” or a “9” in the title. Recording began on May 30, 1968, and 18 takes were recorded. On the final take, the first with a lead vocal, the song continued past the 4 1/2 minute mark and went onto an extended jam. It would end at 10:17 with John shouting to the others and to the control room “OK, I’ve had enough!” The final six minutes were pure chaos with discordant instrumental jamming, plenty of feedback, percussive clicks (which are heard in the song’s introduction as well), and John repeatedly screaming “alright” and moaning along with his girlfriend, Yoko Ono. Ono also spoke random streams of consciousness on the track such as “if you become naked.” This bizarre six-minute section was clipped off the version of what would become “Revolution 1” to form the basis of “Revolution 9.” Yoko’s “naked” line appears in the released version of “Revolution 9” at 7:53. -

Course Outline and Syllabus the Fab Four and the Stones: How America Surrendered to the Advance Guard of the British Invasion

Course Outline and Syllabus The Fab Four and the Stones: How America surrendered to the advance guard of the British Invasion. This six-week course takes a closer look at the music that inspired these bands, their roots-based influences, and their output of inspired work that was created in the 1960’s. Topics include: The early days, 1960-62: London, Liverpool and Hamburg: Importing rhythm and blues and rockabilly from the States…real rock and roll bands—what a concept! Watch out, world! The heady days of 1963: Don’t look now, but these guys just might be more than great cover bands…and they are becoming very popular…Beatlemania takes off. We can write songs; 1964: the rock and roll band as a creative force. John and Paul, their yin and yang-like personal and musical differences fueling their creative tension, discover that two heads are better than one. The Stones, meanwhile, keep cranking out covers, and plot their conquest of America, one riff at a time. The middle periods, 1965-66: For the boys from Liverpool, waves of brilliant albums that will last forever—every cut a memorable, sing-along winner. While for the Londoners, an artistic breakthrough with their first all--original record. Mick and Keith’s tempestuous relationship pushes away band founder Brian Jones; the Stones are established as a force in the music world. Prisoners of their own success, 1967-68: How their popularity drove them to great heights—and lowered them to awful depths. It’s a long way from three chords and a cloud of dust. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

INNOVATION, MEET LIFESTYLE How the U’S New Entrepreneurial Living Space Is Launching Students Into the Maker-Sphere

FALL 2017 INNOVATION, MEET LIFESTYLE How the U’s new entrepreneurial living space is launching students into the maker-sphere. THE COST OF WAR FLASH THE U WHAT HAPPY PEOPLE DO DESERT BLOOMS Continuum_Fall17_cover.indd 1 8/15/17 3:55 PM Continuum_Fall17_cover.indd 3 8/14/17 12:48 PM FALL 2017 VOL. 27 NO. 2 32 Innovation, Meet Lifestyle How the U’s new entrepreneurial living space is launching students into the maker-sphere. 14 What Do We Want in a U President? See responses from students, faculty, administrators, and alumni. 16 What Happy People Do Ed Diener, aka Dr. Happiness, shares wisdom on well-being. 32 20 No Flash in the Pan How “flashing the U” became an iconic, unifying symbol. 26 Reflecting on War Alum Kael Weston examines the human costs of conflict. DEPARTMENTS 2 Feedback 4 Campus Scene 6 Updates 10 Bookshelf 12 Discovery 40 Alum News 48 One More 204 Cover photo by Trina Knudsen 16 26 Continuum_Fall17_TOC Feedback.indd 1 8/15/17 3:01 PM FEEDBACK Publisher William Warren Executive Editor M. John Ashton BS’66 JD’69 Editor minutes and was followed J. Melody Murdock for the rest of the hour by Managing Editor an even more egregious Marcia C. Dibble interview featuring two Associate Editor professors…. Ann Floor BFA’85 Assistant Editor Bradley R. Larsen MS’89 Amanda Taylor Doug Fabrizio Bountiful, Utah Advertising Manager David Viveiros Photo by Austen Diamond Austen by Photo Art Director/Photographer SCIENTIFIC David E. Titensor BFA’91 DOUG FABRIZIO AND I love listening to DISCOVERY AND RADIOWEST RadioWest! The inter- Corporate Sponsors views are so interesting, CLIMATE CHANGE ARUP Laboratories Others may disagree, but We don’t have to spin University Credit Union and as Doug interviews, University of Utah Health I consider Mr. -

Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles' Films

“All I’ve got to do is Act Naturally”: Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles’ Films Submitted by Stephanie Anne Piotrowski, AHEA, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English (Film Studies), 01 October 2008. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which in not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (signed)…………Stephanie Piotrowski ……………… Piotrowski 2 Abstract In this thesis, I examine the Beatles’ five feature films in order to argue how undermining generic convention and manipulating performance codes allowed the band to control their relationship with their audience and to gain autonomy over their output. Drawing from P. David Marshall’s work on defining performance codes from the music, film, and television industries, I examine film form and style to illustrate how the Beatles’ filmmakers used these codes in different combinations from previous pop and classical musicals in order to illicit certain responses from the audience. In doing so, the role of the audience from passive viewer to active participant changed the way musicians used film to communicate with their fans. I also consider how the Beatles’ image changed throughout their career as reflected in their films as a way of charting the band’s journey from pop stars to musicians, while also considering the social and cultural factors represented in the band’s image. -

2008 Annual Report GMHC Fights to End the AIDS Epidemic and Uplift the Lives of All Affected

web of truth 2008 annual report GMHC fights to end the AIDS epidemic and uplift the lives of all affected. From Crisis to Wisdom 2 Message from the Chief Executive Officer and the Chair of the Board of Directors 3 From Education to Legislation 4 From Baby Boo to Baby Boom 6 From Connection to Prevention 8 From Hot Meals to Big Ideals 10 The Frontlines of HIV Prevention 12 Financial Summary 2008 14 Corporate & Foundation Supporters 15 The Founders’ Circle 17 Individual Donors 18 The President’s Council / Friends for Life / Allies Monthly Benefactors / Partners in Planning Event Listings 23 House Tours / Fashion Forward / Savor Toast at Twilight / AIDS Walk 2008 GMHC fights to end the AIDS epidemic and uplift the lives of all affected. Gender 76% Male 23% Female 1% Transgender Race/Ethnicity 31% Black 31% White 30% Latino 3% Asian/Pacific Islander 5% Other/Unknown Sexual Orientation 56% Gay/Lesbian 9% Bisexual 35% Heterosexual Age 19% 29 and under 21% 30–39 33% 40–49 27% 50 and over Residence 14% Bronx 20% Brooklyn 47% Manhattan 12% Queens 1% Staten Island 6% Outside NYC 1 from crisis to wisdom HIV is a disease that thrives in darkness. In For 27 years, GMHC has born witness to HIV silence. In apathy. It thrives when connections from its frontlines. And in those 27 years, remain unseen—when the links between we’ve charted a pandemic that changes con- individuals and communities…between social tinuously and profoundly. Its demographics lives and sexual lives remain broken and have changed. Its challenges have changed. -

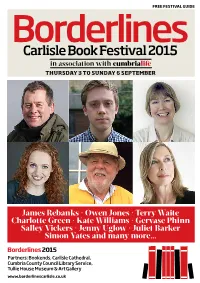

Borderlines 2015

FREE FESTIVAL GUIDE BorderlinesCarlisle Book Festival 2015 in association with cumbrialife THURSDAY 3 TO SUNDAY 6 SEPTEMBER James Rebanks � Owen Jones � Terry Waite Charlotte Green � Kate Williams � Gervase Phinn Salley Vickers � Jenny Uglow � Juliet Barker Simon Yates and many more... Borderlines 2015 Partners: Bookends, Carlisle Cathedral, Cumbria County Council Library Service, Tullie House Museum & Art Gallery www.borderlinescarlisle.co.uk President’s welcome city strolling Rigby Phil Photography The Lanes Carlisle ell done to everyone at The growth in literary festivals in the last image courtesy of BHS Borderlines for making it decade has partly been because the such a resounding reading public, in fact the general public, success, for creating a do like to hear and see real live people for Wliterary festival and making it well and a change, instead of staring at some sort truly a part of the local community, nay, of inanimate box or computer contrap- part of national literary life. It is now so tion. The thing about Borderlines is that well established and embedded that it it is totally locally created and run, a feels as if it has been going for ever, not- for- profit event, from which no one though in fact it only began last year… gets paid. There is a committee of nine yes, only one year ago, so not much to who include representatives from boast about really, but existing- that is an Cumbria County Council, Bookends, achievement in itself. There are now Tullie House and the Cathedral. around 500 annual literary festivals in So keep up the great work. -

Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1St Edition)

R O C K i n t h e R E S E R V A T I O N Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1st edition). (text, 2004) Yngvar B. Steinholt. New York and Bergen, Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. viii + 230 pages + 14 photo pages. Delivered in pdf format for printing in March 2005. ISBN 0-9701684-3-8 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt (b. 1969) currently teaches Russian Cultural History at the Department of Russian Studies, Bergen University (http://www.hf.uib.no/i/russisk/steinholt). The text is a revised and corrected version of the identically entitled doctoral thesis, publicly defended on 12. November 2004 at the Humanistics Faculty, Bergen University, in partial fulfilment of the Doctor Artium degree. Opponents were Associate Professor Finn Sivert Nielsen, Institute of Anthropology, Copenhagen University, and Professor Stan Hawkins, Institute of Musicology, Oslo University. The pagination, numbering, format, size, and page layout of the original thesis do not correspond to the present edition. Photographs by Andrei ‘Villi’ Usov ( A. Usov) are used with kind permission. Cover illustrations by Nikolai Kopeikin were made exclusively for RiR. Published by Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. 401 West End Avenue # 3B New York, NY 10024 USA Preface i Acknowledgements This study has been completed with the generous financial support of The Research Council of Norway (Norges Forskningsråd). It was conducted at the Department of Russian Studies in the friendly atmosphere of the Institute of Classical Philology, Religion and Russian Studies (IKRR), Bergen University. -

Yellowsubmarinesongtrack.Pdf

UK Release: 13 September 1999 US Release: 14 September 1999 Running Time: 45.40 Vinyl: Apple 521 4811 CD: Apple 521 4812 Producers: George MartinIPeter Cobbin Vinyl: Side A: Yellow Submarine; Hey Bulldog; Eleanor Rigby; Love You To; All Together Now; ~ucyIn The Sky With Diamonds; Think For Yourself; Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band; With A Little Help From My Friends Side B: Baby, You're A Rich Man; Only A Northern Song; All You Need Is Love; When I'm Sixty- Four; Nowhere Man; It's All Too Much CD: Yellow Submarine; Hey Bulldog; Eleanor Rigby; Love You To; All Together Now; Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds; Think For Yourself; Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band; With A Little Help From My Friends; Baby, You're A Rich Man; Only A Northern Song; All You Need Is Love; When I'm Sixty-Four; Nowhere Man; It's All Too Much When Yellow Submarine was first released in January 1969, coinciding with the animated Cartoon film, the only Beatles tracks were on side one. There were just six of them - 'Yellow Submarine', 'Only A Northern Song', 'All Together Now', 'Hey Bulldog', 'It's All Too Much' and 'All You Need Is Love' - and only four of them were new. Side two was devoted entirely to George Martin's musical score for the movie. Thirty years later it was decided to restore the film, digitalising the soundtrack in the process, and the songtrack album is a result of that remastering. Released in 1999, it was the first collection of Beatles songs to get a digital remix, but more significantly it dispensed with the film score that had appeared on side two and included instead most of the other songs featured in the film that hadn't appeared on the earlier LP. -

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960S and 1970S by Kathryn B. C

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960s and 1970s by Kathryn B. Cox A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology: History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor James M. Borders Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Jane Fair Fulcher Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Kathryn B. Cox [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6359-1835 © Kathryn B. Cox 2018 DEDICATION For Charles and Bené S. Cox, whose unwavering faith in me has always shone through, even in the hardest times. The world is a better place because you both are in it. And for Laura Ingram Ellis: as much as I wanted this dissertation to spring forth from my head fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead, it did not happen that way. It happened one sentence at a time, some more excruciatingly wrought than others, and you were there for every single sentence. So these sentences I have written especially for you, Laura, with my deepest and most profound gratitude. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it sometimes felt like a solitary process, I wrote this dissertation with the help and support of several different people, all of whom I deeply appreciate. First and foremost on this list is Prof. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, whom I learned so much from and whose patience and wisdom helped shape this project. I am very grateful to committee members Prof. James Borders, Prof. Walter Everett, Prof. -

Study of Children in Care and the Standards Spending Assessment

A MODEL OF THE DETERMINANTS OF EXPENDITURE ON CHILDREN’S PERSONAL SOCIAL SERVICES Results of a study commissioned by the Department of Health from a consortium comprising the University of York, MORI and the National Children’s Bureau Roy A. Carr-Hill, University of York Paul Dixon, Independent Consultant Russell Mannion, University of York Nigel Rice, University of York Kai Rudat, Office for Public Management Ruth Sinclair, National Children’s Bureau Peter C. Smith, University of York All enquiries to Roy Carr-Hill or Peter Smith Centre for Health Economics University of York York YO1 5DD December 1997 A MODEL OF THE DETERMINANTS OF EXPENDITURE ON CHILDREN’S PERSONAL SOCIAL SERVICES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY 2. BACKGROUND 2.1 Children’s Personal Social Services 2.2 Standard Spending Assessments 2.3 Standard Spending Assessment for Children’s Social Services 2.4 Assessment of current methods 2.5 This study 3. ESTIMATING SMALL AREA COSTS OF CHILDREN’S PSS 3.1 Database of all children in contact with social service departments 3.2 Social work frequency contact data 3.3 Social work contact duration data 3.4 Local authority budget data 4. ANALYSIS OF COSTS OF CHILDREN’S PSS 4.1 Constructing the database 4.2 Developing a statistical model 4.3 Results 4.4 Sensitivity analysis 5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS Appendix A: Categories of children in need Appendix B: Authorities participating in the survey Appendix C: Socio-economic variables derived from the Census Appendix D: Modelling methodology 2 1. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY Every year the United Kingdom central government assesses the relative spending needs of English local authorities in respect of the services for which it is responsible. -

Beatles Cover Albums During the Beatle Period

Beatles Cover Albums during the Beatle Period As a companion to the Hollyridge Strings page, this page proposes to be a listing of (and commentary on) certain albums that were released in the United States between 1964 and April 1970. Every album in this listing has a title that indicates Beatles-related content and/or a cover that is a parody of a Beatles cover. In addition, the content of every album listed here is at least 50% Beatles-related (or, in the case of albums from 1964, "British"). Albums that are not included here include, for example, records named after a single Beatles song but which contain only a few Beatles songs: for example, Hey Jude, Hey Bing!, by Bing Crosby. 1964: Nineteen-sixty-four saw the first wave of Beatles cover albums. The earliest of these were released before the release of "Can't Buy Me Love." They tended to be quickly-recorded records designed to capitalize rapidly on the group's expanding success. Therefore, most of these albums are on small record labels, and the records themselves tended to be loaded with "filler." Possibly, the companies were not aware of the majority of Beatle product. Beattle Mash The Liverpool Kids Palace M-777 Side One Side Two 1. She Loves You 1. Thrill Me Baby 2. Why Don't You Set Me Free 2. I'm Lost Without You 3. Let Me Tell You 3. You Are the One 4. Take a Chance 4. Pea Jacket Hop 5. Swinging Papa 5. Japanese Beatles 6. Lookout for Charlie The label not only spells "Beatle" correctly but also lists the artist as "The Schoolboys." The liner notes show that this album was released before the Beatles' trip to America in February, 1964.