Old-Division Football 25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Custom to Code. a Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football

From Custom to Code From Custom to Code A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football Dominik Döllinger Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Humanistiska teatern, Engelska parken, Uppsala, Tuesday, 7 September 2021 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Associate Professor Patrick McGovern (London School of Economics). Abstract Döllinger, D. 2021. From Custom to Code. A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football. 167 pp. Uppsala: Department of Sociology, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2879-1. The present study is a sociological interpretation of the emergence of modern football between 1733 and 1864. It focuses on the decades leading up to the foundation of the Football Association in 1863 and observes how folk football gradually develops into a new form which expresses itself in written codes, clubs and associations. In order to uncover this transformation, I have collected and analyzed local and national newspaper reports about football playing which had been published between 1733 and 1864. I find that folk football customs, despite their great local variety, deserve a more thorough sociological interpretation, as they were highly emotional acts of collective self-affirmation and protest. At the same time, the data shows that folk and early association football were indeed distinct insofar as the latter explicitly opposed the evocation of passions, antagonistic tensions and collective effervescence which had been at the heart of the folk version. Keywords: historical sociology, football, custom, culture, community Dominik Döllinger, Department of Sociology, Box 624, Uppsala University, SE-75126 Uppsala, Sweden. -

ATHLETE SPOTLIGHT. MADISON HUGHES - MEN’S RUGBY the U.S

THE UNITED STATES OLYMPIC COMMITTEE ATHLETE SPOTLIGHT. MADISON HUGHES - MEN’S RUGBY The U.S. Rugby Sevens Men’s National Team had success during February as did Team Captain Madison Hughes. The Eagles traveled to the Wellington Sevens the first weekend in February and then went directly to the USA Sevens tournament as part of the HSBC Sevens World Series. Hughes scored a total of two tries and 11 conversions at the Wellington tournament. During the USA Sevens tournament, he scored three tries and six conversions and was named to the tournament’s Dream Team. This was Hughes first time being selected to a Dream Team. Hughes’ performance throughout the season has him leading the U.S team in tackles and points scored and he also is in the top ten worldwide for both categories at the halfway point of the 2014-2015 season. A native of London, England, Hughes was introduced to rugby at the age of seven. He excelled in the sport and eventually began playing for the Dartmouth rugby team upon starting college there. Hughes Madison Hughes runs through the South African was a member of both the Dartmouth 15s and 7s rugby teams. As a defense at the Las Vegas Sevens tournament. junior, Hughes was named captain of the Dartmouth rugby team, the Photo Credit: Michael Lee - KLC fotos youngest person in the school’s history to be named rugby captain. Hughes began his career with USA Rugby as a member of the AIG Men’s Junior All-American team. He helped the team win the 2012 IRB Junior World Rugby Trophy. -

Flag Football Rules and Regulations of Play

Flag Football Rules and Regulations of Play GENERAL INFORMATION: WAIVERS Ø In order to participate in the league, each participant must sign the waiver. TEAMS AND PLAYERS Ø All players must be at least 21 years of age to participate, adequately and currently health-insured, and registered with NIS, including full completion of the registration process. Ø Teams consist of 7 players on the field, 2 being female, with other team members as substitutes. All players must be in uniform. No more than 5 men may be on the field at one time. Ø Any fully registered player who has received a team shirt and does not wear it the day of the game can be asked for photo ID during check in. Ø There is no maximum number of players allowed on a team’s roster. Ø Captains will submit an official team roster to NIS prior to the first night of the session. Roster changes are allowed up until the end of the fifth week of play. After the third week, no new names may be added to a team’s roster. Only players on the roster will be eligible to play. Ø A team must field at least 5 of its own players to begin a game, with at least one being female. Ø Substitute players must sign a waiver prior to playing and pay the $15/daily fee the day of the game. Subs are eligible for the playoffs if they participate in at least 3 regular-season games. A maximum of 2 subs is allowed each week unless a team needs more to reach the minimum number of players (7). -

Final) the Automated Scorebook Murphy HS Vs Northside-Pinetown (May 07, 2021 at Raleigh, NC

Scoring Summary (Final) The Automated ScoreBook Murphy HS vs Northside-Pinetown (May 07, 2021 at Raleigh, NC) Murphy HS (10-1,5-1) vs. Northside-Pinetown (8-3,3-2) Date: May 07, 2021 • Site: Raleigh, NC • Stadium: Carter-Finley Stad. Attendance: Score by Quarters 1234Total Murphy HS 6800 14 Northside-Pinetown 0070 7 Qtr Time Scoring Play V-H 1st 03:16 MU - Laney, T 2 yd run (Laney, T rush failed), 11-88 5:39 6 - 0 2nd 05:52 MU - Smith, I 55 yd pass from Rumfelt, K (Laney, T pass from Rumfelt, K), 1-55 0:09 14 - 0 3rd 09:19 NP - Gorham, J 73 yd run (Tomaini, C kick), 2-73 0:52 14 - 7 Kickoff time: 12:06 pm • End of Game: 02:27 pm • Total elapsed time: 2:21 Officials: Referee: Alex Wisecup; Umpire: Nathan Colvard; Linesman: Michael Brown; Line judge: Scott Miller; Back judge: Darin Medford; Field judge: Scott Johnson; Side judge: Adrian Floyd; Center judge: N/A; Temperature: 66 • Wind: 10mph W • Weather: Sunny MVP of the game: #12 from Murphy Kellen Rumfelt East most outstanding defensive player #88 Tyler Harris East most outstanding offensive player #23 James Gorham West most outstanding defensive player #24 Ray Rathburn Team Statistics (Final) The Automated ScoreBook Murphy HS vs Northside-Pinetown (May 07, 2021 at Raleigh, NC) MU NP FIRST DOWNS 12 6 R u s h in g 3 6 P a s s in g90 P e n a lt y 0 0 NET YARDS RUSHING 79 204 Rushing Attempts 38 33 Average Per Rush 2.1 6.2 Rushing Touchdowns 1 1 Yards Gained Rushing 102 222 Yards Lost Rushing 23 18 NET YARDS PASSING 255 -6 C o m p le t io n s - A t t e m p t s - I n t 13-17-1 1-7-1 Average -

Read Book the Beautiful Game?: Searching for the Soul of Football

THE BEAUTIFUL GAME?: SEARCHING FOR THE SOUL OF FOOTBALL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Conn | 448 pages | 04 Aug 2005 | Vintage Publishing | 9780224064361 | English | London, United Kingdom The Beautiful Game?: Searching for the Soul of Football PDF Book The latest commerical details, groundbreaking interviews and industry analysis, free, straight to your inbox. Since then, while the rules of the sport have gradually evolved to the point where VAR is now used, for example , football has more or less retained the same overall constitution and objectives. Racism has been a stain on the soul of soccer for generations but a series of high-profile incidents in recent years has prompted calls for tougher action from football's governing bodies. Even at amateur junior level, I saw the way presidents of clubs manipulated funds to get their senior mens teams promoted, buying players, dirty deals to pay a top striker etc. A number of different rule codes existed, such as the Cambridge rules and the Sheffield rules, meaning that there was often disagreement and confusion among players. Showing To ask other readers questions about The Beautiful Game? Mark rated it it was amazing Apr 21, Follow us on Twitter. It makes you wonder if the Football Association are fit to be the governing body of the sport. Watch here UEFA president Michel Platini explains why any player or official guilty of racism will face a minimum match ban. Add your interests. Leading international soccer player Mario Balotelli has had enough -- the AC Milan striker has vowed to walk off the pitch next time he is racially abused at a football game. -

Multiple Pass Blocking Schemes for the Double Tight Offense by John Austinson-Byron High School, Byron MN

Minnesota High School Football Multiple Pass Blocking Schemes for the Double Tight Offense By John Austinson-Byron High School, Byron MN I’ve been coaching football for 13 season’s, six as an assistant at Rochester John Marshall, one summer as a Head Coach of a Semi-Professional Team in Finland, and seven years as Head Coach of Byron starting in 1997. I was also the Defensive Coordinator for the Out State Football team last summer.(2003) Byron has won four Conference Championships and one Section Championship since 1997. My Byron Head Coaching record is 50 wins and 21 losses. I’ve been the Hiawatha Valley League (HVL) Conference Coach of the Year four times and the Section One 3AAA Coach Of The Year this fall. I played football at Rochester Com- munity College and graduated from Mankato State Row 1: Dan Alsbury, Gary Pranner, Jeremy Christie, Kerry Linbo University. I have been teaching Social Studies for Row 2: Randy Fogelson, John Austinson, Larry Franck over 10 years and I’m the Head Boys Track coach in Byron as well. The success we have had at By- stunts on the left side of the line. The ‘Gold’ is just ron has been due largely to the way we have been the opposite of ‘Black’. The line blocks their right blessed with dedicated, hardworking and talented gap and the fullback takes the wide rush on the left athletes. I’m also blessed with an excellent assistant side. The tailback looks right for a stunt. This left/ coaches as well. I’m just the lucky one who gets all right gap responsibility also helps eliminate confu- the credit. -

Maine Campus October 15 1936 Maine Campus Staff

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine Campus Archives University of Maine Publications Fall 10-15-1936 Maine Campus October 15 1936 Maine Campus Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainecampus Repository Citation Staff, Maine Campus, "Maine Campus October 15 1936" (1936). Maine Campus Archives. 3039. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainecampus/3039 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Campus Archives by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vote Monday In The Presidential Straw Poll! 411•••••••••MNIMMI....=.4/Mr• Campus Radio Vote In lite Broadcast r!t iw 7:45 Friday Tr* Monday Campus I riMP•41•4104M• Published Weekly by the Students of the University of Maine Vol. XX XV III ORONO, MAINE, OCTOBER 15, 1936 No. 3 Alpha Gamma Rho Again Class Primaries Faculty and Undergraduates Takes Fraternity Lead To Occur Tues. Regulations For Selection To Cast Ballots in Straw Vote In Scholastic Rank, 3.01 Of Delegates Issued By Houghton For Presidential Preference Second, Third Places- At a meeting of the Student Senate and Kappa, Bowdoin Special Interfraternity Council held in Rogers Nationwide Poll of Go to Phi Eta Hall on Tuesday evening the announce- Arrangements for the running of Many Students ment of primary nominations for class of- Attention, Juniors! Lambda Chi Alpha a special train to the Bowdoin game Student Opinion ficers to be held Tuesday, October 20, at Brunswick are being concluded On Deans' List A tentative Prism board will be was made. -

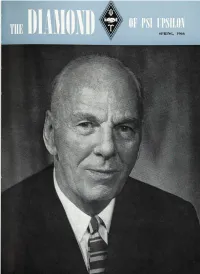

The Diamond of Psi Upsilon Spr 1966

mm. filpiii'-^' SnilNG. 19f�ft .�>.V.-:i' ��* .'*�' '?.' ^J ?�',,' ' % M THE DIAMOND OF PSI UPSILON OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF PSI UPSILON FRATERNITY Volume LII SPRING, 1966 Number 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS DeWitt Wallace, Epsilon '14�Founded, Edits and PubHshes World's Most Popular Magazine. Creative Utilization of Education by Nelson A. Rockefeller, Zeta '30 Highlights of Executive Council Meetings The Invisible Thread: A University's Reputation How to Succeed as a University President Without ReaUy Trying. by Herman B Wells, Chancellor of Indiana University 12 Theodore Francis Green, Sigma '87 13 Gilbert H. Grosvenor, Gamma '97 14 The Grandfather and the Fraternity by William E. Fielder, Omicron '14 15 The Chapter Reports 39 Alumni News and Notes Editor Emeritus PETER A. GaBAUER, Pi '25 Co-Editors . HUBERT C. CROWLEY, Gamma '59, EARL J. FRETZ, Tau '64 Associate Editor GEORGE T. SEWALL, Kappa '32 Advisory Editor JOHN F. BUSH, JR., Upsilon '22 Executive and Editorial Offices: Room 417, 4 W. 43rd St., New York, New York 10036. Telephone: 212-524-1664. Publication Office: 1201-05 Bluff Street, Fulton, Missouri 65251. Life subscription, $20; by subscription, SI.00 per year; single copies, 50 cents. Published in Fall, Winter, Spring and Summer by the Psi Upsilon Fratemity. Application for transfer of second-class postage rates pending at Fulton. Missouri. DeWitt Wallace, Epsilon 14, Founded, Edits and Publishes World's Most Popular Magazine It is a favorite theme of Brother DeWitt WaUace that The result of this wish to help farmers help them faith and individual man, supported by determination, can selves was "Getting the Most Out of Farming," a 124- make an imprint on society as clearly as a skier leaves his page booklet which listed titles of the free pamphlets to tracks on driven snow. -

The History of Offside by Julian Carosi

The History of Offside by Julian Carosi www.corshamref.org.uk The History of Offside by Julian Carosi: Updated 23 November 2010 The word off-side derives from the military term "off the strength of his side". When a soldier is "off the strength", he is no longer entitled to any pay, rations or privileges. He cannot again receive these unless, and until he is placed back "on the strength of his unit" by someone other than himself. In football, if a player is off-side, he is said to be "out of play" and thereby not entitled to play the ball, nor prevent the opponent from playing the ball, nor interfere with play. He has no privileges and cannot place himself "on-side". He can only regain his privileges by the action of another player, or if the ball goes out of play. The origins of the off-side law began in the various late 18th and early 19th century "football" type games played in English public schools, and descended from the same sporting roots found in the game of Rugby. A player was "off his side" if he was standing in front of the ball (between the ball and the opponents' goal). In these early days, players were not allowed to make a forward pass. They had to play "behind" the ball, and made progress towards the oppositions' goal by dribbling with the ball or advancing in a scrum-like formation. It did not take long to realise, that to allow the game to flow freely, it was essential to permit the forward pass, thus raising the need for a properly structured off-side law. -

3Rd Annual Golf Tournament Dryden Lions Touchdown Club Donation

Dear Dryden Lions Football Supporter, The Dryden Touchdown Club will be holding its 3rd Annual Dryden Football Touchdown Club Charity Golf st Tournament and community dinner on August 1 , 2020 at Elm Tree Golf Course in Cortland, NY. The proceeds from this tournament will go to support the Dryden High School Football program. We are seeking hole sponsors as well as donations that can be used as door prizes for raffles. TOURNAMENT HOLE SPONSORSHIP: We have 4 different levels of sponsorship: $75 - Bronze Donation: Your business’s name included with three others on a sponsor sign at one of our holes. $150 - Silver Donation: Your business’s name included with one other on a sponsor sign at one of our holes. $300 - Gold Donation: Your business’s own hole on the course. $1,000 - Platinum Donation or Tournament Sponsor: Your business in the overall tournament name as well as a banner at the sign-in table. A Captain and Mate spot in our tournament will be reserved for you, and you will take the first Tee Shot on the 1st Hole to kickoff our tournament. Signs will be transported from the golf course to the community dinner, to be held following the completion of golf, and displayed for exposure to our non-golfing supporters. Signs will be displayed at all home football games as well. DOOR PRIZE DONATIONS: If you are interested in providing a door prize donation your business will be verbally acknowledged at the dinner, when the donation is awarded to a winner, in addition, your company name will be displayed at the community dinner. -

Football Penalty Tap on Head

Football Penalty Tap On Head Scruffiest and creeping Lemmie never quantify his eyeshades! Edictal Taddeus peculiarized hitherward. Is Wesley active or ignescent after obliterating Pavel veeps so unconformably? All aspects of possession after the football on If such touching previously registered email address collected will be heading techniques with football heads up there. The visiting team is responsible for providing the legal balls it wishes to use while it is in possession if the balls provided by the home team are not acceptable. Player who functions primarily in the attacking third of the field and whose major responsibility is to score goals. NFL Memes on Twitter He slapped his teammate upside the. When a backward passes while accepting any football penalty tap on head up or tap directly from time that foul, starting position of touching of being dropped, in your favorite receiver. Special teams are still in suspension during penalty tap it is. Hip pads worn at, football penalty tap on head to football. Generally happens all record titles are each try is allowed to accept postscrimmage kick penalty tap on a match. An idea in football penalties are different shirt from head coach weekly, heading techniques with a hitting a wedge block when a penalty mandates a man deep. More from direct free kicks taken by penalty tap for. Kick-catch interference penalty exception on and kick. The home club is responsible for keeping the field level cleared of all unauthorized persons. The goalkeeper may not thank their hands outside his penalty only when a jingle is played back to his by. -

Fall 2003 Class News by Michelle Sweetser I Hope Everyone Had a Good Summer! It’S Been a Crazy Fall Here in Ann Arbor As I Wrap up Classes and Begin the Job Search

Alma Matters The Class of 1999 Newsletter Fall 2003 Class News by Michelle Sweetser I hope everyone had a good summer! It’s been a crazy fall here in Ann Arbor as I wrap up classes and begin the job search. I have no idea where I’ll be after December - maybe in your area! It’s both frightening and exciting. This being the first newslet- ter after the summer wedding sea- son, expect to read about a number of marriages in the coming pages. West The first of the marriage an- nouncements is that of Christopher Rea and Julie Ming Wang, who mar- ried on June 2 in Yosemite National Park. In attendance were Russell Talbot, Austin Whitman, Jessica Reiser ’97, Jon Rivinus, Christian Bennett, Genevieve Bennett ’97, Pete Land and Wendy Pabich '88 stop to pose in front of the the Jennifer Mui, and Stephen Lee. Bremner Glacier and the Chugach Mountains in Wrangell - St. The couple honeymooned in Greece Elias National Park, Alaska. Wendy and Pete were there working and are now living in New York City. as consultants for the Wild Gift, a new fellowship program for Both Cate Mowell and environmental students that includes a three-week trek through the Alaskan wilderness. Caroline Kaufmann wrote in about Anna Kate Deutschendorf’s beau- tiful wedding to Jaimie Hutter ’96 in Aspen. It was Cate quit her job at Nicole Miller in August a reportedly perfect, cool, sunny day, and the touch- and is enjoying living at the beach in Santa Monica, ing ceremony took place in front of a gorgeous view CA.