Classics 3: Tributes Program Notes the Time out Suite Chris Brubeck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Double Keyboard Concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

The double keyboard concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Waterman, Muriel Moore, 1923- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 18:28:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318085 THE DOUBLE KEYBOARD CONCERTOS OF CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH by Muriel Moore Waterman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: JAMES R. -

BIOGRAPHIES, INTERVIEWS, ITINERARIES, WRITINGS & NOTES BOX 1: BIOGRAPHY,1940S-1950S

HOLT ATHERTON SPECIAL COLLECTIONS MS4: BRUBECK COLLECTION SERIES 1: PAPERS SUBSERIES D: BIOGRAPHIES, INTERVIEWS, ITINERARIES, WRITINGS & NOTES BOX 1: BIOGRAPHY,1940s-1950s 1D.1.1: Biography, 1942: “Iola Whitlock marries Dave Brubeck,” Pacific Weekly, 9-25-42 1.D.1.2: Biography, 1948: Ralph J. Gleason. “Long awaited Garner in San Francisco…Local boys draw comment” [Octet at Paradise in Oakland], Down Beat (12-1-48), pg. 6 1.D.1.3: Biography, 1949 a- “NBC Conservatory of Jazz,” San Francisco, Apr 5, 1949 [radio program script for appearance by the Octet; portion of this may be heard on Fantasy recording “The Dave Brubeck Octet”; incl. short biographies of all personnel] b- Lifelong Learning, Vol. 19:6 (Aug 8, 1949) c- [Bulletin of University of California Extension for 1949-50, the year DB taught “Survey of Jazz”] d- “Jazz Concert Set” 11-4-49 e- Ralph J. Gleason. “Finds little of interest in lst Annual Jazz Festival [San Francisco],” Down Beat (12-16-49) [mention of DB Trio at Burma Lounge, Oakland; plans to play Ciro’s, SF at beginning of 1950], pg. 5 f- “…Brubeck given musical honors” Oakland Tribune, December 16, 1949 g- DB “Biographical Sketch,” ca Dec 1949 h- “Pine Tree Club Party at Home of Mrs. A. Ellis,” <n.s.> n.d. [1940s] i- “Two Matrons are Hostesses to Pine Tree Club,” <n.s.> n.d. [1940s] (on same page as above) 1.D.1.4: Biography, 1950: “Dave Brubeck,” Down Beat, 1-27-50 a- Ralph J. Gleason. “Swingin the Golden Gate: Bay Area Fog,” Down Beat 2- 10-50 [DB doing radio show on ABC] 1.D.1.5: BIOGRAPHY, 1951: “Small band of the year,” Jazz 1951---Metronome Yearbook, n.d. -

Elliott Carter Works List

W O R K S Triple Duo (1982–83) Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation Basel ORCHESTRA Adagio tenebroso (1994) ............................................................ 20’ (H) 3(II, III=picc).2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(4):BD/ 4bongos/glsp/4tpl.bl/cowbells/vib/2susp.cym/2tom-t/2wdbl/SD/xyl/ tam-t/marimba/wood drum/2metal block-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Allegro scorrevole (1996) ........................................................... 11’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-perc(4):timp/glsp/xyl/vib/ 4bongos/SD/2tom-t/wdbl/3susp.cym/2cowbells/guiro/2metal blocks/ 4tpl.bl/BD/marimba-harp-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Anniversary (1989) ....................................................................... 6’ (H) 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(2):vib/marimba/xyl/ 3susp.cym-pft(=cel)-strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Boston Concerto (2002) .............................................................. 19’ (H) 3(II,III=picc).2.corA.3(III=bcl).3(III=dbn)-4.3.3.1-perc(3):I=xyl/vib/log dr/4bongos/high SD/susp.cym/wood chime; II=marimba/log dr/ 4tpl.bl/2cowbells/susp.cym; III=BD/tom-t/4wdbls/guiro/susp.cym/ maracas/med SD-harp-pft-strings A Celebration of Some 100 x 150 Notes (1986) ....................... 3’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(1):glsp/vib-pft(=cel)- strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Concerto for Orchestra (1969) .................................................. -

JS BACH (1685-1750): Violin and Oboe Concertos

BACH 703 - J. S. BACH (1685-1750) : Violin and Oboe Concertos Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21 st , l685, the son of Johann Ambrosius, Court Trumpeter for the Duke of Eisenach and Director of the Musicians of the town of Eisenach in Thuringia. For many years, members of the Bach family throughout Thuringia had held positions such as organists, town instrumentalists, or Cantors, and the family name enjoyed a wide reputation for musical talent. By the year 1703, 18-year-old Johann Sebastian had taken up his first professional position: that of Organist at the small town of Arnstadt. Then, in 1706 he heard that the Organist to the town of Mülhausen had died. He applied for the post and was accepted on very favorable terms. However, a religious controversy arose in Mülhausen between the Orthodox Lutherans, who were lovers of music, and the Pietists, who were strict puritans and distrusted art. So it was that Bach again looked around for more promising possibilities. The Duke of Weimar offered him a post among his Court chamber musicians, and on June 25, 1708, Bach sent in his letter of resignation to the authorities at Mülhausen. The Weimar years were a happy and creative time for Bach…. until in 1717 a feud broke out between the Duke of Weimar at the 'Wilhelmsburg' household and his nephew Ernst August at the 'Rote Schloss’. Added to this, the incumbent Capellmeister died, and Bach was passed over for the post in favor of the late Capellmeister's mediocre son. Bach was bitterly disappointed, for he had lately been doing most of the Capellmeister's work, and had confidently expected to be given the post. -

Paul Jacobs, Elliott Carter, and an Overview of Selected Stylistic Aspects of Night Fantasies

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2016 Paul Jacobs, Elliott aC rter, And An Overview Of Selected Stylistic Aspects Of Night Fantasies Alan Michael Rudell University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Rudell, A. M.(2016). Paul Jacobs, Elliott aC rter, And An Overview Of Selected Stylistic Aspects Of Night Fantasies. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3977 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAUL JACOBS, ELLIOTT CARTER, AND AN OVERVIEW OF SELECTED STYLISTIC ASPECTS OF NIGHT FANTASIES by Alan Michael Rudell Bachelor of Music University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2004 Master of Music University of South Carolina, 2009 _____________________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Joseph Rackers, Major Professor Charles L. Fugo, Committee Member J. Daniel Jenkins, Committee Member Marina Lomazov, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Alan Michael Rudell, 2016 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my thanks to the members of my committee, especially Joseph Rackers, who served as director, Charles L. Fugo, for his meticulous editing, J. Daniel Jenkins, who clarified certain issues pertaining to Carter’s style, and Marina Lomazov, for her unwavering support. -

Programnotes Brahms Double

Please note that osmo Vänskä replaces Bernard Haitink, who has been forced to cancel his appearance at these concerts. Program One HundRed TwenTy-SeCOnd SeASOn Chicago symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 18, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, October 19, 2012, at 8:00 Saturday, October 20, 2012, at 8:00 osmo Vänskä Conductor renaud Capuçon Violin gautier Capuçon Cello music by Johannes Brahms Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 (Double) Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo RenAud CApuçOn GAuTieR CApuçOn IntermIssIon Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 un poco sostenuto—Allegro Andante sostenuto un poco allegretto e grazioso Adagio—Allegro non troppo, ma con brio This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Comments by PhilliP huscher Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany. Died April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria. Concerto for Violin and Cello in a minor, op. 102 (Double) or Brahms, the year 1887 his final orchestral composition, Flaunched a period of tying up this concerto for violin and cello— loose ends, finishing business, and or the Double Concerto, as it would clearing his desk. He began by ask- soon be known. Brahms privately ing Clara Schumann, with whom decided to quit composing for he had long shared his most inti- good, and in 1890 he wrote to his mate thoughts, to return all the let- publisher Fritz Simrock that he had ters he had written to her over the thrown “a lot of torn-up manuscript years. -

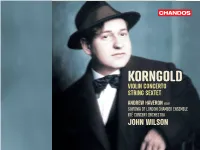

Korngold Violin Concerto String Sextet

KORNGOLD VIOLIN CONCERTO STRING SEXTET ANDREW HAVERON VIOLIN SINFONIA OF LONDON CHAMBER ENSEMBLE RTÉ CONCERT ORCHESTRA JOHN WILSON The Brendan G. Carroll Collection Erich Wolfgang Korngold, 1914, aged seventeen Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897 – 1957) Violin Concerto, Op. 35 (1937, revised 1945)* 24:48 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Dedicated to Alma Mahler-Werfel 1 I Moderato nobile – Poco più mosso – Meno – Meno mosso, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Poco meno – Tempo I – [Cadenza] – Pesante / Ritenuto – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Meno, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Meno – Più mosso 9:00 2 II Romanze. Andante – Meno – Poco meno – Mosso – Poco meno (misterioso) – Avanti! – Tranquillo – Molto cantabile – Poco meno – Tranquillo (poco meno) – Più mosso – Adagio 8:29 3 III Finale. Allegro assai vivace – [ ] – Tempo I – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco meno (maestoso) – Fließend – Più tranquillo – Più mosso. Allegro – Più mosso – Poco meno 7:13 String Sextet, Op. 10 (1914 – 16)† 31:31 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Herrn Präsidenten Dr. Carl Ritter von Wiener gewidmet 3 4 I Tempo I. Moderato (mäßige ) – Tempo II (ruhig fließende – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III. Allegro – Tempo II – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Tempo II – Allmählich fließender – Tempo III – Wieder Tempo II – Tempo III – Drängend – Tempo I – Tempo III – Subito Tempo I (Doppelt so langsam) – Allmählich fließender werdend – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo I – Tempo II (fließend) – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III – Ruhigere (Tempo II) – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Sehr breit – Tempo II – Subito Tempo III 9:50 5 II Adagio. Langsam – Etwas bewegter – Steigernd – Steigernd – Wieder nachlassend – Drängend – Steigernd – Sehr langsam – Noch ruhiger – Langsam steigernd – Etwas bewegter – Langsam – Sehr breit 8:27 6 III Intermezzo. -

The Italian Double Concerto: a Study of the Italian Double Concerto for Trumpet at the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna, Italy

The Italian Double Concerto: A study of the Italian Double Concerto for Trumpet at the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna, Italy a document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Performance Studies Division – The University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music 2013 by Jason A. Orsen M.M., Kent State University, 2003 B.M., S.U.N.Y Fredonia, 2001 Committee Chair: Dr. Vivian Montgomery Prof. Alan Siebert Dr. Mark Ostoich © 2013 Jason A. Orsen All Rights Reserved 2 Table of Contents Chapter I. Introduction: The Italian Double Concerto………………………………………5 II. The Basilica of San Petronio……………………………………………………11 III. Maestri di Cappella at San Petronio…………………………………………….18 IV. Composers and musicians at San Petronio……………………………………...29 V. Italian Double Concerto…………………………………………………………34 VI. Performance practice issues……………………………………………………..37 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..48 3 Outline I. Introduction: The Italian Double Concerto A. Background of Bologna, Italy B. Italian Baroque II. The Basilica of San Petronio A. Background information on the church B. Explanation of physical dimensions, interior and effect it had on a composer’s style III. Maestri di Cappella at San Petronio A. Maurizio Cazzati B. Giovanni Paolo Colonna C. Giacomo Antonio Perti IV. Composers and musicians at San Petronio A. Giuseppe Torelli B. Petronio Franceschini C. Francesco Onofrio Manfredini V. Italian Double Concerto A. Description of style and use B. Harmonic and compositional tendencies C. Compare and contrast with other double concerti D. Progression and development VI. Performance practice issues A. Ornamentation B. Orchestration 4 I. -

Danny Elfman's Violin Concerto

Danny Elfman’s Violin Concerto Friday, October 18 Today’s concert focuses not only on the renowned 10:30am concert music of Danny Elfman, but on a style of music that doesn’t tell a complete narrative. Rather, today’s selections paint a picture of a feeling, or an emotion, or a mysterious land- scape, by only using the power of music. Read on to find out more! Danny Elfman, American Composer (1953- ) Danny Elfman is an American composer most well known for his film music. He has composed music for film and TV such as The Simpsons, Men in Black, and Avengers: Age of Ultron. and has worked with pioneer- ing directors such as Tim Burton, Sam Raimi, Guillermo del Toro and Ang REPERTOIRE Lee. In 2004, Elfman began writing for the concert hall, such as Serenada Schizophrana (2005), Rabbit and Rogue (2008), and Eleven Eleven (2017). ELFMAN Concerto: “Eleven Eleven” Danny Elfman work- STRAUSS ing with longtime creative collaborator Death and and director, Tim Bur- Transfiguration, ton, on Alice in Wonderland (2010). Dance of the Seven Veils from Salome Concerto for Violin & Orchestra: “Eleven Eleven” composed in 2017, duration is 15 minutes This concerto, or larger-scale piece for an orchestra and a solo instrument, is approximately 40 minutes in duration and is divided into four movements. It features lyrical melodies inspired by early 20th century music, as well as more modern rhythms and har- monies. The title comes from the measure count, which hap- pens to be exactly 1,111 meas- ures long. The piece was written in collaboration with violinist Sandy Cameron. -

Eli Yamin Celebrates the Dave Brubeck Quartet Curriculum Guide

Eli Yamin Celebrates the Dave Brubeck Quartet Curriculum Guide Eli Yamin Celebrates the Dave Brubeck Quartet Overview These six videos are presented and performed by jazz and blues pianist, composer, singer, producer and educator Eli Yamin. The videos vary in length from 3 to 12 minutes. The title of the series aptly denotes the content because Eli Yamin and his group of master musicians truly do “celebrate” 5 songs of Dave Brubeck. Each video examines and performs a specific song and its unique qualities. Although the focus is always the music, the lessons easily apply to literacy and language arts standards, grades 6-12. The amount of time spent on the lessons can be decided by the teachers, depending on students’ interest, needs, and planning. Below is a brief summary of the content of each video to help teachers decide which best suits their curriculum. It is recommended that all the videos be studied in order to provide a full scope of Brubeck’s music, but the lessons and videos can each stand alone. Dave Brubeck Brief Background Dave Brubeck was a famous jazz pianist, composer, and bandleader who lived from 1920 to 2012. He founded the Dave Brubeck Quartet in 1951 after playing for several years in his group called the Dave Brubeck Octet. His group became very popular in the 1950s, most notably for his combination of great melodies, strong sense of swing, and unusual meters and rhythms from around the globe. Some of his more popular songs are "Blue Rondo a la Turk," "In Your Own Sweet Way" and "The Duke." He collaborated with quartet member Paul Desmond on numerous compositions; Desmond’s “Take Five” became the first jazz instrumental to sell more than one million copies. -

By Chau-Yee Lo

Dramatizing the Harpsichord: The Harpsichord Music of Elliott Carter by Chau-Yee Lo “I regard my scores as scenarios, auditory scenarios, for performers to act out their instruments, dramatizing the players as individuals and partici- pants in the ensemble.”1 Elliott Carter has often stated that this is his creative standpoint, his works from solo to orchestral pieces growing from the dramatic possibilities inherent in the sounds of the instruments. In this article I will investigate how and to what extent this applies to Carter’s harp- sichord music. Carter has written two works for the harpsichord: Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello, and Harpsichord was completed in 1952, and Double Concerto for Harpsichord and Piano with Two Chamber Orchestras in 1961. Both commissions were initiated by harpsichordists: the first by Sylvia Marlowe (1908–81) and the Harpsichord Quartet of New York, for whom the Sonata was written, the latter by Ralph Kirkpatrick (1911–84), who had been Carter’s fellow student at Harvard. Both works encapsulate a significant development in Carter’s technique of composition, and bear evidence of his changing approach to music in the 1950s. Shortly after completing the Double Concerto Carter started writing down the interval combinations he had frequently been using. This exercise continued and became more systematic over the next two decades, and the result is now published as the Harmony Book.2 Carter came to write for the harpsichord for the first time in the Sonata. Here the harpsichord is the only soloist, the other instruments being used as a frame. In particular Carter emphasizes the wide range of tone colours available on the modern harpsichord, echoing these in the different musi- cal characters of the other instruments. -

PROGRAM NOTES: “Violin Concerto”

PROGRAM NOTES: “Violin Concerto” I believe that one of the most rewarding aspects of life is exploring and discovering the magic and mysteries held within our universe. For a composer this thrill often takes place in the writing of a concerto…it is the exploration of an instrument’s world, a journey of the imagination, confronting and stretching an instrument’s limits, and discovering a particular performer’s gifts. The first movement of this concerto, written for the violinist, Hilary Hahn, carries a somewhat enigmatic title of “1726”. This number represents an important aspect of such a journey of discovery, for both the composer and the soloist. 1726 happens to be the street address of The Curtis Institute of Music, where I first met Hilary as a student in my 20th Century Music Class. An exceptional student, Hilary devoured the information in the class and was always open to exploring and discovering new musical languages and styles. As Curtis was also a primary training ground for me as a young composer, it seemed an appropriate tribute. To tie into this title, I make extensive use the intervals of unisons, 7ths, and 2nds, throughout this movement. The excitement of the first movement’s intensity certainly deserves the calm and pensive relaxation of the 2nd movement. This title, “Chaconni”, comes from the word “chaconne”. A chaconne is a chord progression that repeats throughout a section of music. In this particular case, there are several chaconnes, which create the stage for a dialog between the soloist and various members of the orchestra. The beauty of the violin’s tone and the artist’s gifts are on display here.