CANTU-MASTERSREPORT-2020.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Conference on Environmental, Cultural, Economic & Social Sustainability 2020 Delegate Packet

International Conference on Environmental, Cultural, Economic & Social Sustainability 2020 Delegate Packet Dear Delegate, Thank you for participating in the Sixteenth International Conference on Environmental, Cultural, Economic & Social Sustainability. We are pleased you will be joining us in Santiago, Chile at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile & the University of Chile. We hope you are looking forward to coming together with colleagues and members of the On Sustainability Research Network this January. In preparation for the conference, we have put together some information that we hope will prove useful to you as you begin to prepare for the conference and your arrival in Santiago. In this document, you will find a variety of information on subjects, such as transportation, hotel and travel, activities and extras, conference registration, equipment, and session types. This packet is a starting point for your preparations, and we realize you may have some additional questions after reviewing the material here. For any questions that remain please visit the conference website at onsustainability.com/2020-conference. We hope your planning goes well, and we look forward to seeing you in Santiago! Page 2 Table of Contents Venue and Conference Information Conference Venue ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Registration Desk Hours and Location ................................................................................................................ -

UIT SUBTEL University of Chile 1

ITU Symposium and Workshop on small satellite regulation and communication systems Santiago de Chile, Chile, 7-9 November 2016 GENERAL INFORMATION A. THE EVENT 1. Focal Points: UIT SUBTEL University of Chile 1. (english) Yvon Henri 1. Luis Ramírez 1. Dr. Marcos Díaz Quezada Phone: +41 22 730 5536 Phome: +56 224 213 651 Phone: +56 9 90510540 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] 2. (español) Sergio Scarabino 2. Ing. Alex Becerra Saavedra Phone: +56 979 670 968 Phone: +56 9 78126798 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] 2. Venue Sitie: Enrique d’Etigny Lyon Auditorium, Beauchef Poniente Building, Physic Sciences and Mathematics Faculty, University of Chile Address: Avenida Beauchef 851, Santiago Centro, Santiago, Chile. Map External View of Enrique D’Etigny Auditorium - 1 - Enrique D’Etigny Auditorium (red circle) y sourrounding How to get there: METRO: The venue is 700-800 meters from the Metro stations Line L2 -Orange (see Metro map at the end of the document, and more detail in Section 3) - Parque O'higgins (when arriving in S-N sense) - Toesca (when arriving in N-S sense) BUS: Transantiago buses that pass near Auditorium Enrique D'Etigny are: 506, 506e, 507, 509, 510, 121 (see details in section 2) Accommodation and hotel reservations Event has not official hotels, and there are not hotels around the event site. It is suggested the nearest hotel zone in Comuma Providencia (4-5 km east from the venue) which has hotels of various categories and prices. -

UBB Travel Information

TRAVEL INFORMATION FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS Dirección General de Relaciones Internacionales - 2007 VISAS ¾ International students must apply for a Student Visa at the Chilean consulate in their home country once they have received a letter of admission from Universidad del Bío-Bío. To find the nearest Consular Office, check the following web site of the Chilean Ministry of External Relations: http://www.minrel.cl/pages/misiones/index.html. ¾ A Student Visa allows the holder to study at educational establishments recognized by the government of Chile. It is valid for one year and may be renewed. ¾ International students must register their visa with the Policia de Investigaciones-Extranjería, the Investigations Police and Immigration Office. Bring your passport, two photocopies of the page in your passport showing your personal information, two photocopies of the page containing your visa, and three passport-size (4 cm x 4 cm) color photos with your full name and passport number. You will be issued a “Certificado de Registro”, for which you will be charged a fee of 800 Chilean pesos. This document must then be presented to the “Servicio de Registro Civil” (Civil Registry); where you will be issued a Chilean Identification Card. The fee for the card is 3,200 Chilean pesos. Students who are staying in Chile less than 30 days do not need to register their visa. • Address and office hours of Policía de Investigaciones de Chile- Extranjería: In Concepción: Angol Nº 815, phone 56-41-2236124, office hours: from 9:00 to 12:30 and from 15:00 to 17:00 hrs. In Chillán: Vega de Saldías Nº 350, phone 56-42-237660, office hours: from 8:00 to 12:30 and from 15:00 to 17:00 hrs. -

Registration Document 2016/17

* TABLE OF CONTENTS REGISTRATION DOCUMENT 2016/17 DESCRIPTION CORPORATE 1 OF GROUP ACTIVITIES AFR 3 5 GOVERNANCE 137 Industry characteristics 4 Chairman’s report 138 Competitive position 7 Executive Committee AFR 181 Strategy 8 Statutory Auditors’ report prepared Offering 9 in accordance with Article L. 225‑235 of the French Commercial Code Research and development 15 on the report prepared by the Chairman of the Board of Alstom AFR 182 MANAGEMENT REPORT Interests of the officers 2 ON CONSOLIDATED and employees in the share capital 183 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS – Related‑party agreements and commitments 190 AFR FISCAL YEAR 2016/17 AFR 19 Statutory Auditors 190 Main events of fiscal year 2016/17 20 Objectives for 2020 confirmed 21 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: Commercial performance 22 6 ALSTOM’S SOCIAL Orders backlog 24 RESPONSIBILITY 191 Income Statement 24 Sustainable development strategy 192 Free cash flow 26 Designing sustainable mobility solutions 200 Net Debt 27 Environmental performance 207 Equity 27 Social performance 215 Non‑GAAP financial indicators definitions 28 Relationships with external stakeholders 233 Synthesis of indicators/key figures 2016/17 244 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AFR 31 Report by one of the Statutory Auditors, 3 Consolidated income statement 32 appointed as an independent third party , on the consolidated environmental, Statutory financial statements 98 labour and social information presented in the management report 247 AFR RISK FACTORS 119 Table of compulsory CSR information AFR 250 4 Risks in relation to the economic environment -

Metro De Santiago WHERE the CITY MEETS

Metro de Santiago WHERE THE CITY MEETS www.metro.cl WHERE THE CITY MEETS Metro de Santiago Guaripola Guachaca Dióscoro Rojas recently described “the Metro is the most democratic and republican place we have in Santiago” this statement best describes the metro as a socio-economic melting pot that offers beyond a means of transportations to this great city. RESEARCH BY Joseph Philips 2 [ JULY 2019 ] BUSINESS EXCELLENCE BUSINESS EXCELLENCE [ JULY 2019 ] 3 METRO DE SANTIAGO hen Business Excellence first visited of lines 3 and 6, totalling 37 kilometres of beyond our 2013 article. It was first conceived Metro de Santiago, nearly 6 years ago track and 28 stations. Maintaining the same over 30 years ago but faced significant delays, W at the end of 2013, its management was standards across the extended and new lines “The highlight of the largely due to the 1985 earthquake that shook about to implement a plan for infrastructure would be a challenge - Metro de Santiago US$400 million investment Chile’s capital city. Its arrival is not only a improvements in the network. This was to system is renowned for its low waiting time valuable addition to the metro system - halving involve the purchase of new train carriages, the for passengers. We were looking forward was to be the construction the journey times for many commuters in the modernization of older trains (which were to to seeing how everything shaped out in the of lines 3 and 6, totalling city - but also, in some ways, symbolic: a sign be fitted with positioning systems, in-carriage intervening eight years. -

Global Report Global Metro Projects 2020.Qxp

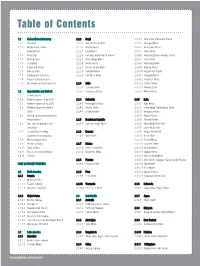

Table of Contents 1.1 Global Metrorail industry 2.2.2 Brazil 2.3.4.2 Changchun Urban Rail Transit 1.1.1 Overview 2.2.2.1 Belo Horizonte Metro 2.3.4.3 Chengdu Metro 1.1.2 Network and Station 2.2.2.2 Brasília Metro 2.3.4.4 Guangzhou Metro Development 2.2.2.3 Cariri Metro 2.3.4.5 Hefei Metro 1.1.3 Ridership 2.2.2.4 Fortaleza Rapid Transit Project 2.3.4.6 Hong Kong Mass Railway Transit 1.1.3 Rolling stock 2.2.2.5 Porto Alegre Metro 2.3.4.7 Jinan Metro 1.1.4 Signalling 2.2.2.6 Recife Metro 2.3.4.8 Nanchang Metro 1.1.5 Power and Tracks 2.2.2.7 Rio de Janeiro Metro 2.3.4.9 Nanjing Metro 1.1.6 Fare systems 2.2.2.8 Salvador Metro 2.3.4.10 Ningbo Rail Transit 1.1.7 Funding and financing 2.2.2.9 São Paulo Metro 2.3.4.11 Shanghai Metro 1.1.8 Project delivery models 2.3.4.12 Shenzhen Metro 1.1.9 Key trends and developments 2.2.3 Chile 2.3.4.13 Suzhou Metro 2.2.3.1 Santiago Metro 2.3.4.14 Ürümqi Metro 1.2 Opportunities and Outlook 2.2.3.2 Valparaiso Metro 2.3.4.15 Wuhan Metro 1.2.1 Growth drivers 1.2.2 Network expansion by 2025 2.2.4 Colombia 2.3.5 India 1.2.3 Network expansion by 2030 2.2.4.1 Barranquilla Metro 2.3.5.1 Agra Metro 1.2.4 Network expansion beyond 2.2.4.2 Bogotá Metro 2.3.5.2 Ahmedabad-Gandhinagar Metro 2030 2.2.4.3 Medellín Metro 2.3.5.3 Bengaluru Metro 1.2.5 Rolling stock procurement and 2.3.5.4 Bhopal Metro refurbishment 2.2.5 Dominican Republic 2.3.5.5 Chennai Metro 1.2.6 Fare system upgrades and 2.2.5.1 Santo Domingo Metro 2.3.5.6 Hyderabad Metro Rail innovation 2.3.5.7 Jaipur Metro Rail 1.2.7 Signalling technology 2.2.6 Ecuador -

The Operator's Story Appendix: Santiago's Story

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Appendix: Santiago’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London 1 The Operator’s Story: Notes from Santiago Case Study Interviews – February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in Santiago. These notes are based upon 11 meetings between 16th and 20th May 2016. This document will form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London or the World Bank. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and Metro de Santiago. However, in some cases it is noted that a comment was made by an individual external not employed by Metro de Santiago (‘external commentator’), where it is appropriate to draw a distinction between views expressed by Metro de Santiago themselves and those expressed about their organisation. List -

Tren NS-1974 N°1 Del Metro De Santiago Expediente Para La Declaración De Monumento Nacional

Tren NS-1974 N°1 del Metro de Santiago Expediente para la Declaración de Monumento Nacional Santiago Vera Bustamante Santiago, febrero de 2015 Solicitud para Declaración de Monumento Nacional en la categoría “Monumento Histórico” del Tren NS-74 N° 1 del Metro de Santiago que se compone de las unidades M0001-P3001-N1001-R4001-M0002 Placa de fabricación equipos NS-74 1 Expediente Técnico Solicitud Monumento Histórico NS-74 del Metro de Santiago INDICE GENERAL 1. FUNDAMENTOS GENERALES DE LA PETICIÓN 4 2. ANTECEDENTES HISTÓRICOS DE LOS TRENES NS-74 7 a) Sobre los primeros trenes con neumáticos 7 b) Expansión del sistema de rodado neumático a otros países 10 c) Elección del sistema rodado para el Metro de Santiago 11 3. TRENES “NS-74” (Neumático Santiago año 1974) 14 a) Origen y fabricación 14 b) Partidas o series de trenes 17 c) Elementos o coches que componen el tren NS-74 20 d) Modificaciones a la configuración original 23 e) Otras características originales de los trenes NS-74 24 f) Cuadros resumen de características técnicas 27 4. NS-74 NÚMERO 01 32 a) Coches originales del tren N° 01 y su actual estado 33 Coche M0001 33 Coche P3001 35 Coche N1001 37 Coche R4001 39 Coche M0002 41 b) Nómina de trenes en servicio, su composición y ubicación actual 43 c) Sobre la necesidad de conservación de estos equipos en particular 47 d) Motivos técnicos que justificarían la rehabilitación de los trenes NS-74 55 e) ¿Por qué el NS-74 N° 01? 61 f) Fundamentos legales de la solicitud 62 g) Experiencias y problemáticas similares de conservación patrimonial en Chile 63 2 Expediente Técnico Solicitud Monumento Histórico NS-74 del Metro de Santiago h) Experiencias internacionales de conservación de trenes de metro 65 i) Propuesta de conservación del Tren NS- 74 N° 01 68 5. -

Avenid a Libertad Dor Berna Rdo O'hig Cro Ggins 136. Own Plaza Santiago a Hotel. , Chile

Crown Plaza Hotel. Avenida Libertador Bernardo O’Higgins 136. Santiago, Chile. Pan American Health Organization World Health Organization Ministry of Health, Chile 1 WELCOMING REMARKS 25 years ago, during the Regional Conference of the Pan American Health Organization held in Caracas, the countries of the Americas started a reform of mental health care services on behalf of the dignity and rights of people. The document approved at this conference, better known as the Caracas Declaration, has become a technical and ethical reference that has guided plans and actions of the Region within the last years. Since then, many countries have been advancing. However, the majority still has not achieved the goals, due to ongoing social, political and economic changes that impact the context in which reform processes are developing in these countries of the Americas. During the last decade, new exigencies and obligations based on human rights of people with disabilities were developed and, in turn determined the mission of each state and their society. These new missions led to technical exigencies and new normative standards for the development of practices concordant with human rights that translate into their everyday lives. Recently and in accordance with the States, both the World Health Organization and the Pan American Health Organization developed Mental Health Action Plans for the present decade. In our region these plans represent a continuation of the reform composed in Caracas. Today we assemble with the intent to review the achievements thus far, determine remaining steps, anticipate challenges and establish commitments that we as countries and as a Region will take on in order to accomplish objectives of the Mental Health Action Plan for the following decade. -

GP Santiago 2018: Travel Guide

GP Santiago 2018: Travel Guide Based on: Nicolás Rosa’s GP travel guide 2017. Revised and Updated by: Gabriel Contreras and José Cartes (2018) GP Santiago 2018: Travel Guide Welcome Traveller! You must be asking where has your spark taken you this time and why have you ended up here. Well, let me introduce you to my world and give you some useful information for the upcoming adventure... Chile is an everflowing mana plane located by the very southern end of the multiverse, its inhabitants are friendly most of the times. But be careful, some of these lands are also full of danger. Among residents you'll find a bunch of mages, geomancers, artificers and all sorts of creatures coming from the vast sea, glorious mountains, dense forests, infinite plains and deep marshes, beautiful landscapes this place can offer to your senses. Perhaps, you'll have some time to visit them later, but there's something to do first: You've been summoned here for a massive planeswalker encounter in which you'll have the chance to show your actual strength and amazing skills... who knows? Maybe you'll rise up victorious by the end of it. The gathering will take place at Gran Palace hotel in Satiago city, Chile. In order to get there safe from Phyrexians and other dark forces is highly recommended the use of some of the following tips and data. Good luck, Planeswalker! You will need it. (Unidentified telemancer's voice in your head) GP Santiago 2018: Travel Guide 1. ENTERING CHILE To enter Chile, you have to present your identification documents, like your ID card and/or passport. -

The Plan Regulador Metropolitano De Santiago: An

Transactions on the Built Environment vol 23, © 1996 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3509 The Plan Regulador Metropolitano de Santiago: an integrated approach to urban transport planning? C.R. Rivasplata San Francisco Planning Department, 1660 Mission Street, San Francisco, California 94103, USA Abstract This paper reviews the urban transport component of the Plan Regulador Metropolitano de Santiago (Chile), a master plan for growth in the area. This planning document has important implications for transport planning in Santiago: it provides the groundwork for establishing linkages between land use zoning and transport investment decisions; it sets spatial limits to urban expansion; and it establishes a set of residential densities. One of the most difficult challenges for the Greater Santiago area is to develop a comprehensive master plan that will accommodate the transport needs of its 37 municipalities (comunas) and make the city a more desirable place to live. Some of the principal factors contributing to environmental degradation in Santiago, such as air pollution and traffic congestion, are caused by the inefficient provision of transport services. Therefore, it is important that this plan clearly define the role of urban transport in the economic development of the metropolis. This paper concludes that while the Plan plays a key role in the reduction of travel times, energy consumption and agricultural deterioration, it mistakenly proposes to satisfy increased travel demand through an expansion in road capacity and identifies roadway improvements that fall under the jurisdiction of individual comunas. However, many of these comunas lack resources and are unable to generate the revenues necessary to finance these improvements. -

Santiago De Chile Survival Guide

Santiago de Chile Survival Guide Contact: [email protected] Santiago de Chile | Survival Guide This small guide will help you move through the city with ease and confidence. Remember to adjust your watch to the local Time Zone: GMT -3:00. 1. Phone Calls The country code for Chile is 56, the city code for Santiago is 2. The telephone numbers are usually 8 digits, 8 for cell phones. For long distance calls (national) you need to choose the region code. For example, for a call from everywhere in Chile to Viña del Mar you should dial: 56 (country) + 32 (code for Viña) + 2 (a two) + number. If you want to call abroad, you will need a carrier. For example: 123 (carrier) + 0 (international call) + country code + city code + number. From cell phones to fixed line, a 0 plus the city code must be added. In this case, you have to use "02" before the number for Santiago. From fixed lines to cell phones, add 9 and then the number (i.e.: 9-12345678). From cell phone to cell phone you just have to dial the cell phone number (i.e.: 12345678). 2. City-Airport-City 2.1 Taxi Expensive, safe and fast. They are located on the first floor of the International Central Hall. Reference cost: US$ 30 – US$ 36 from airport to Las Condes area. Suggestions: TaxiOficial SCL Transvip http://www.taxioficial.cl/ http://www.transvip.cl/ [email protected] Santiago de Chile | A Survival Guide | 2 2.2 Transfer (shuttles) The Transfers Stands are located on the first floor of the Airport (some by the luggage claim) and they are cheaper than the taxis, quite comfortable, but take longer to reach destiny as the trips are shared.