Sacred and Secular Crossovers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name: Teacher

Name: Teacher: Key Words There are many key words in History!! In the word search below are some of the ore common words. Try to find them, then see which words you can define (you can us a dictionary or the internet to help you). H A P P E N C W V C S M Q B I Y I J Y R O T S I H W Y M S Y K O V Q D T D N D E N E T I M E L I N E B A A B F U O L W C E G F V T R X Y N R R E M Y O R C E T Z T W E K I N P L A C E Y H H Q T U Y A H L U V Y U Y X E Y J S G N K E G U I T C L K T U O J N I F H O R V P M H I B T Y O E N C H R O N O L O G Y P W B Q E U E V D O E O H O S F W D I P C S P W P B M A W HISTORIAN ________________________________________________________ PAST______________________________________________________________ TIMELINE__________________________________________________________ EVENT_____________________________________________________________ YEAR______________________________________________________________ DATE______________________________________________________________ MONTH____________________________________________________________ AGO_______________________________________________________________ CHRONOLOGY_______________________________________________________ HISTORY___________________________________________________________ PLACE______________________________________________________________ HAPPEN____________________________________________________________ How is time divided up? Put the following words in order, from the shortest to the longest. Century Hour Second Decade Year Week Month Millennium Day Minute Draw a line to match the words below to their definition: Decade 100 years Century 1000 years Week 10 Years Millennium 365 days Year 7 Days Why do you think that knowing this is important for history? __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ What are BC, BCE, AD and CE? Historians often talk about years as being BC or BCE and AD or CE. -

Data-Model Comparisons of Tropical Hydroclimate Changes Over the Common Era

manuscript submitted to Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 1 Data-Model Comparisons of Tropical Hydroclimate Changes Over the Common Era 2 A. R. Atwood1*, D. S. Battisti2, E. Wu2, D. M. W. Frierson2, J. P. Sachs3 3 1Florida State University, Dept. of Earth Ocean and Atmospheric Science, Tallahassee, FL, USA 4 2University of Washington, Dept. of Atmospheric Sciences, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 5 3University of Washington, School of Oceanography, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 6 7 Corresponding author: Alyssa Atwood ([email protected]) 8 9 Key Points: 10 • A synthesis of 67 tropical hydroclimate records from 55 sites indicate several regionally- 11 coherent patterns of change during the Common Era 12 • Robust patterns include a regional drying event from 800-1000 CE and a range of tropical 13 hydroclimate changes ~1400-1700 CE 14 • Poor agreement between the centennial-scale changes in the reconstructions and transient 15 model simulations of the last millennium 16 manuscript submitted to Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 17 Abstract 18 We examine the evidence for large-scale tropical hydroclimate changes over the Common Era 19 based on a compilation of 67 tropical hydroclimate records from 55 sites and assess the 20 consistency between the reconstructed hydroclimate changes and those simulated by transient 21 model simulations of the last millennium. Our synthesis of the proxy records reveal several 22 regionally-coherent patterns on centennial timescales. From 800-1000 CE, records from the 23 eastern Pacific and northern Mesoamerica indicate a pronounced drying event relative to 24 background conditions of the Common Era. In addition, 1400-1700 CE is marked by pronounced 25 hydroclimate changes across the tropics, including an inferred strengthening of the South 26 American summer monsoon, weakened Asian summer monsoons, and fresher conditions in the 27 Maritime Continent. -

How Long Is a Year.Pdf

How Long Is A Year? Dr. Bryan Mendez Space Sciences Laboratory UC Berkeley Keeping Time The basic unit of time is a Day. Different starting points: • Sunrise, • Noon, • Sunset, • Midnight tied to the Sun’s motion. Universal Time uses midnight as the starting point of a day. Length: sunrise to sunrise, sunset to sunset? Day Noon to noon – The seasonal motion of the Sun changes its rise and set times, so sunrise to sunrise would be a variable measure. Noon to noon is far more constant. Noon: time of the Sun’s transit of the meridian Stellarium View and measure a day Day Aday is caused by Earth’s motion: spinning on an axis and orbiting around the Sun. Earth’s spin is very regular (daily variations on the order of a few milliseconds, due to internal rearrangement of Earth’s mass and external gravitational forces primarily from the Moon and Sun). Synodic Day Noon to noon = synodic or solar day (point 1 to 3). This is not the time for one complete spin of Earth (1 to 2). Because Earth also orbits at the same time as it is spinning, it takes a little extra time for the Sun to come back to noon after one complete spin. Because the orbit is elliptical, when Earth is closest to the Sun it is moving faster, and it takes longer to bring the Sun back around to noon. When Earth is farther it moves slower and it takes less time to rotate the Sun back to noon. Mean Solar Day is an average of the amount time it takes to go from noon to noon throughout an orbit = 24 Hours Real solar day varies by up to 30 seconds depending on the time of year. -

Common Era Sea-Level Budgets Along the U.S. Atlantic Coast ✉ Jennifer S

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22079-2 OPEN Common Era sea-level budgets along the U.S. Atlantic coast ✉ Jennifer S. Walker 1,2 , Robert E. Kopp 1,2, Timothy A. Shaw 3, Niamh Cahill 4, Nicole S. Khan5, Donald C. Barber 6, Erica L. Ashe 1,2, Matthew J. Brain7, Jennifer L. Clear8, D. Reide Corbett 9 & Benjamin P. Horton 3,10 Sea-level budgets account for the contributions of processes driving sea-level change, but are 1234567890():,; predominantly focused on global-mean sea level and limited to the 20th and 21st centuries. Here we estimate site-specific sea-level budgets along the U.S. Atlantic coast during the Common Era (0–2000 CE) by separating relative sea-level (RSL) records into process- related signals on different spatial scales. Regional-scale, temporally linear processes driven by glacial isostatic adjustment dominate RSL change and exhibit a spatial gradient, with fastest rates of rise in southern New Jersey (1.6 ± 0.02 mm yr−1). Regional and local, temporally non-linear processes, such as ocean/atmosphere dynamics and groundwater withdrawal, contributed between −0.3 and 0.4 mm yr−1 over centennial timescales. The most significant change in the budgets is the increasing influence of the common global signal due to ice melt and thermal expansion since 1800 CE, which became a dominant contributor to RSL with a 20th century rate of 1.3 ± 0.1 mm yr−1. 1 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. 2 Rutgers Institute of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. -

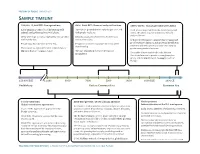

Answer Key Sample Timeline

HISTORY OF FOOD | ANSWER KEY SAMPLE TIMELINE 150,000–11,000 BCE: Pre-agriculture 6000–3000 BCE: Dawn of early civilizations 1600s–1800s: Global agricultural evolution Early humans acquired food by hunting wild Agriculture provided more calories per acre and Food plants imported from the Americas spread animals and gathering from wild plants. tied people to places. across the globe; improved nutrition helped Diets were high in fruits, vegetables, lean protein Densely populated settlements evolved into reduce disease. and healthy fats. towns, then cities. Refrigerated transport, improved processing and preservation techniques and growing distribution People may have lived into their 70s. People become free to pursue interests other than farming. networks allowed farmers to ship their surplus There were no signs of the diet-related chronic goods over greater distances. illnesses that are common today. The rise of political elites created social inequalities. Favorable climate and fertile soils allowed American farmers to produce enough surplus grain, and eventually meat, to supply much of Europe. 150 ,000 BCE 11 ,000 9000 7000 5000 3000 1000 BCE 1000 CE Prehistory Before Common Era Common Era 11,000–5000 BCE: 6000 BCE–present: Cycles of boom and bust 1800s–present: Global transition to agriculture Industrialization of the U.S. food system Increases in food production competed against population 11,000 BCE: Agriculture appeared in the growth, resource degradation, changing climate, droughts, Early 1900s: Synthetic fertilizer was invented. Fertile Crescent. and other drivers of famine. Farmers became more dependent on chemical 6000 BCE: Most farm animals had become The decline of Sumer, Greece, Rome and other ancient and fossil fuel inputs. -

Dionysius Exiguus Name: Date

Name: Date: Numbering Years Ancient calendars were generally based on the calendar, this is AD 622. Most of 2013 is part of the beginning of a ruler's reign. For example, a certain Islamic year AH1434. AH is a Latin phrase that can year would be identified as the third be translated as “the year of the journey.” year of Hammurabi’s rule. The Hebrew calendar is used for Jewish religious Most people today use the services. The Hebrew year 5774 began at sunset on Western calendar (also known as September 4, 2013. Years are marked AM on the the Gregorian calendar) for Hebrew calendar for a Latin phrase that means “the everyday purposes. About AD525, beginning of the world.” a Christian monk named Dionysius Exiguus The Chinese calendar is used for festivals and marked the year Christ was born as 1. The Western holidays in many East Asian nations. In the Chinese calendar tells us we live in 2013, which is sometimes calendar, most of 2013 is known as the Year of the written AD 2013. AD refers to the anno Domini, a Snake. Latin phrase that means “the year of the Lord.” On Western calendars there are ten years in a The years before the birth of Christ are numbered decade, one hundred years in a century, and one backward from his birth. The year before AD 1 was 1 thousand years in a millennium. This is considered BC, or one year “before Christ.” the twenty-first century of the When referring to dates before Dionysius Exiguus Common Era. -

In Interdisciplinary Studies of Climate and History

PERSPECTIVE Theimportanceof“year zero” in interdisciplinary studies of climate and history PERSPECTIVE Ulf Büntgena,b,c,d,1,2 and Clive Oppenheimera,e,1,2 Edited by Jean Jouzel, Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de L’Environ, Orme des Merisiers, France, and approved October 21, 2020 (received for review August 28, 2020) The mathematical aberration of the Gregorian chronology’s missing “year zero” retains enduring potential to sow confusion in studies of paleoclimatology and environmental ancient history. The possibility of dating error is especially high when pre-Common Era proxy evidence from tree rings, ice cores, radiocar- bon dates, and documentary sources is integrated. This calls for renewed vigilance, with systematic ref- erence to astronomical time (including year zero) or, at the very least, clarification of the dating scheme(s) employed in individual studies. paleoclimate | year zero | climate reconstructions | dating precision | geoscience The harmonization of astronomical and civil calendars have still not collectively agreed on a calendrical in the depths of human history likely emerged from convention, nor, more generally, is there standardi- the significance of the seasonal cycle for hunting and zation of epochs within and between communities and gathering, agriculture, and navigation. But difficulties disciplines. Ice core specialists and astronomers use arose from the noninteger number of days it takes 2000 CE, while, in dendrochronology, some labora- Earth to complete an orbit of the Sun. In revising their tories develop multimillennial-long tree-ring chronol- 360-d calendar by adding 5 d, the ancient Egyptians ogies with year zero but others do not. Further were able to slow, but not halt, the divergence of confusion emerges from phasing of the extratropical civil and seasonal calendars (1). -

Chronology Activity Sheet

What Is Chronology Chronology? The skill of putting events into time order is called chronology. History is measured from the first recorded written word about 6,000 years ago and so historians need to have an easy way to place events into order. Anything that happened prior to written records is called ‘prehistory’. To place events into chronological order means to put them in the order in which they happened, with the earliest event at the start and the latest (or most recent) event at the end. Put these events into chronological order from your morning Travelled to school Cleaned teeth 1. 2. 3. 4. Got dressed Woke up 5. 6. Had breakfast Washed my face How do we measure time? There are many ways historians measure time and there are special terms for it. Match up the correct chronological term and what it means. week 1000 years year 10 years decade 365 days century 7 days millennium 100 years What do BC and AD mean? When historians look at time, the centuries are divided between BC and AD. They are separated by the year 0, which is when Jesus Christ was born. Anything that happened before the year 0 is classed as BC (Before Christ) and anything that happened after is classed as AD (Anno Domini – In the year of our Lord). This means we are in the year 2020 AD. BC is also known as BCE and AD as CE. BCE means Before Common Era and CE means Common Era. They are separated by the year 0 just like BC and AD, but are a less religious alternative. -

Calendars from Around the World

Calendars from around the world Written by Alan Longstaff © National Maritime Museum 2005 - Contents - Introduction The astronomical basis of calendars Day Months Years Types of calendar Solar Lunar Luni-solar Sidereal Calendars in history Egypt Megalith culture Mesopotamia Ancient China Republican Rome Julian calendar Medieval Christian calendar Gregorian calendar Calendars today Gregorian Hebrew Islamic Indian Chinese Appendices Appendix 1 - Mean solar day Appendix 2 - Why the sidereal year is not the same length as the tropical year Appendix 3 - Factors affecting the visibility of the new crescent Moon Appendix 4 - Standstills Appendix 5 - Mean solar year - Introduction - All human societies have developed ways to determine the length of the year, when the year should begin, and how to divide the year into manageable units of time, such as months, weeks and days. Many systems for doing this – calendars – have been adopted throughout history. About 40 remain in use today. We cannot know when our ancestors first noted the cyclical events in the heavens that govern our sense of passing time. We have proof that Palaeolithic people thought about and recorded the astronomical cycles that give us our modern calendars. For example, a 30,000 year-old animal bone with gouged symbols resembling the phases of the Moon was discovered in France. It is difficult for many of us to imagine how much more important the cycles of the days, months and seasons must have been for people in the past than today. Most of us never experience the true darkness of night, notice the phases of the Moon or feel the full impact of the seasons. -

Ap World History (2018)

AP WORLD HISTORY (2018) Summit High School Summit, NJ Grade Level / Content Area: th 12 Grade AP World History Developed by Ashley M. Sularz Summit High School 2013-2014 Revised 2018-2019 Length of Course: 30 weeks of active teaching new material before the AP Examination 2 weeks of review before the AP Examination 3 weeks following the AP examination (special projects) 5 class days = 1 week Course Reference: College Board. AP World History: Course and Exam Description: (2011). http://apcentral.collegeb oard.com/apc/public/repository/AP_WorldHistoryCED_Effective_Fall_2011.pdf Course of Study: This course follows a chronological development that begins around 8,000 B.C.E to the present day. The periodization and pace of the course is as follows: Unit 1: Moving Toward Global Interactions c. 1200. to c. 1450 10% (3 weeks) Unit 2: Global Interactions c. 1450 to c. 1750 30% (9 weeks) Unit 3: Industrialization & Global Integration c. 1750 to c. 1900 30% (9 weeks) Unit 4: Accelerating Global Change & Realignments c. 1900 to the Present 30% (9 weeks) Unit 7: Review & Post-AP Exam (5 weeks) *This program uses the designation B.C.E. (before the common era) and C.E. (common era); these labels correspond to B. C. (before Christ) and A.D. (anno Domini) respectively 2 Course Description: AP World History is a full year survey course meant to be the equivalent of a freshman college course and can earn students college credit. This course will cover the evolution of cross-cultural global contacts and examine the way in which the world’s major civilizations have interacted since 1200 C.E. -

Periodization and “The Medieval Globe”: a Conversation

PERIODIZATION AND “THE MEDIEVAL GLOBE”: A CONVERSATION KATHLEEN DAVIS and MICHAEL PUETT The idea for this dialogue emerged out of “The Medieval Globe: Com muni cation, Connectivity, and Exchange,” a conference held at the Uni ver sity of Illinois in April of 2012. Its authors represent different scholarly disciplines and fields of study, and yet both presented papers that engaged with very similar issues—and that touched off a series of broader discussions among all conference participants. The editors of The Medieval Globe decided that it would be beneficial to capture the dynamics of their conversation in the form of a dialogue. Kathleen Davis For a scholar like myself who has been dedicated to exposing the mechanisms, logic, and effects of medieval/modern periodization, a project titled The Medieval Globe suggests great potential but at the same time raises some serious concerns. Most obviously, the Middle Ages is a European historiographi cal category. Globalizing it can thus have the effect of fitting the entire world into western European—a Europe’s self-centered narrative of historical time. Moreover, the Middle Ages was process that to an important extent enabled the idea of Europe as an internally constituted as exclusively European—indeed, as specifically and nonEuropean areas from the ancientmedievalmodern progression. Thus unified entity, and at the same time had the effect of excluding eastern European certain fundamental histories—such as those of politics, sovereignty, law, and phi in certain power centers of Christian Europe, despite the very obvious fact that for losophy—were written as moving from Athens to Rome and thence to florescence economics and world trade, were in the east and south. -

Timelines * the Basics *

Timelines * The basics *! This edition designed for individual student use and & self-checking: answers included. * What is it used for? A timeline is used to show historical events in chronological order. Chronological Order = The order in which events occur. * How does it get set up? • Events go in order from left to right, or top to bottom.! • Beginning and end dates should be clearly marked.! • Year marks should be placed on the line in even intervals (1 year, 10 years, 100 years, 1000 years... depends on length of timeline).! • Events may be written directly above or below the line. Be sure the year each event happened is clear.! ! Like this.... 5000 B.C.E. 4000 B.C.E. 3000 B.C.E. 2000 B.C.E. NOT this... 8000 B.C.E. 3000 B.C.E. 2000 B.C.E. 1000 B.C.E. OR this... 5000 B.C.E. 3000 B.C.E. 2000 B.C.E. 4000 B.C.E. * AND DEFINITELY NOT THIS!!!! 8000 B.C.E. 1000 B.C.E. 2000 C.E. 3000 B.C.E. All of these rules are designed to help timeline accurately make a VISUAL of the passage of time. So you can easily SEE which events came first, and the passage of time between each event. * On your paper, draw a timeline starting at 4000 B.C.E. and ending at 4000 C.E. * Include a hash mark to indicate every 1000 years! * When you are finished, go to to the next page to check your answer. * Your turn to try!!! Check with a partner! 4000 3000 2000 1000 1000 2000 3000 4000 B.C.E.