Ap World History (2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name: Teacher

Name: Teacher: Key Words There are many key words in History!! In the word search below are some of the ore common words. Try to find them, then see which words you can define (you can us a dictionary or the internet to help you). H A P P E N C W V C S M Q B I Y I J Y R O T S I H W Y M S Y K O V Q D T D N D E N E T I M E L I N E B A A B F U O L W C E G F V T R X Y N R R E M Y O R C E T Z T W E K I N P L A C E Y H H Q T U Y A H L U V Y U Y X E Y J S G N K E G U I T C L K T U O J N I F H O R V P M H I B T Y O E N C H R O N O L O G Y P W B Q E U E V D O E O H O S F W D I P C S P W P B M A W HISTORIAN ________________________________________________________ PAST______________________________________________________________ TIMELINE__________________________________________________________ EVENT_____________________________________________________________ YEAR______________________________________________________________ DATE______________________________________________________________ MONTH____________________________________________________________ AGO_______________________________________________________________ CHRONOLOGY_______________________________________________________ HISTORY___________________________________________________________ PLACE______________________________________________________________ HAPPEN____________________________________________________________ How is time divided up? Put the following words in order, from the shortest to the longest. Century Hour Second Decade Year Week Month Millennium Day Minute Draw a line to match the words below to their definition: Decade 100 years Century 1000 years Week 10 Years Millennium 365 days Year 7 Days Why do you think that knowing this is important for history? __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ What are BC, BCE, AD and CE? Historians often talk about years as being BC or BCE and AD or CE. -

How to Make a Time Capsule That Tells the Story of Covid-19

How to make a time capsule that tells the story of Covid-19 The 2020 Covid-19 pandemic will go down in the history books, but a time capsule will teach future generations all about what lockdown was really like. COVID 19 time capsules are an easy project to get involved with, plus they’re totally unique to every person. What are Covid-19 time capsules? Time capsules are containers of some kind which hold a selection of objects, picked because they have a special meaning in the time that we’re living in. For example, time capsules have been found from as early as 1874 in the UK with photographs and letters, describing daily events happening that year. Often, time capsules are buried underground, beneath floorboards or stone slabs. For example, in 2015 one was buried under the Millennium Dome in London to be opened in 2050. With the coronavirus pandemic, we are all living through an important moment in history. Many people want to help future generations learn about this time using time capsules, full of things that show what life under lockdown was like. So, how do you make your own Covid-19 time capsule? How to create a COVID-19 time capsule While everyone will make theirs differently depending on what they think is important, these are some of the basics that you should do to create your time capsule. Adding more will make it more fascinating when it’s opened! Choose your box If you’re burying your time capsule, it’s important to use a sturdy container that won’t rot or fall apart over time. -

Data-Model Comparisons of Tropical Hydroclimate Changes Over the Common Era

manuscript submitted to Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 1 Data-Model Comparisons of Tropical Hydroclimate Changes Over the Common Era 2 A. R. Atwood1*, D. S. Battisti2, E. Wu2, D. M. W. Frierson2, J. P. Sachs3 3 1Florida State University, Dept. of Earth Ocean and Atmospheric Science, Tallahassee, FL, USA 4 2University of Washington, Dept. of Atmospheric Sciences, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 5 3University of Washington, School of Oceanography, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 6 7 Corresponding author: Alyssa Atwood ([email protected]) 8 9 Key Points: 10 • A synthesis of 67 tropical hydroclimate records from 55 sites indicate several regionally- 11 coherent patterns of change during the Common Era 12 • Robust patterns include a regional drying event from 800-1000 CE and a range of tropical 13 hydroclimate changes ~1400-1700 CE 14 • Poor agreement between the centennial-scale changes in the reconstructions and transient 15 model simulations of the last millennium 16 manuscript submitted to Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 17 Abstract 18 We examine the evidence for large-scale tropical hydroclimate changes over the Common Era 19 based on a compilation of 67 tropical hydroclimate records from 55 sites and assess the 20 consistency between the reconstructed hydroclimate changes and those simulated by transient 21 model simulations of the last millennium. Our synthesis of the proxy records reveal several 22 regionally-coherent patterns on centennial timescales. From 800-1000 CE, records from the 23 eastern Pacific and northern Mesoamerica indicate a pronounced drying event relative to 24 background conditions of the Common Era. In addition, 1400-1700 CE is marked by pronounced 25 hydroclimate changes across the tropics, including an inferred strengthening of the South 26 American summer monsoon, weakened Asian summer monsoons, and fresher conditions in the 27 Maritime Continent. -

How Long Is a Year.Pdf

How Long Is A Year? Dr. Bryan Mendez Space Sciences Laboratory UC Berkeley Keeping Time The basic unit of time is a Day. Different starting points: • Sunrise, • Noon, • Sunset, • Midnight tied to the Sun’s motion. Universal Time uses midnight as the starting point of a day. Length: sunrise to sunrise, sunset to sunset? Day Noon to noon – The seasonal motion of the Sun changes its rise and set times, so sunrise to sunrise would be a variable measure. Noon to noon is far more constant. Noon: time of the Sun’s transit of the meridian Stellarium View and measure a day Day Aday is caused by Earth’s motion: spinning on an axis and orbiting around the Sun. Earth’s spin is very regular (daily variations on the order of a few milliseconds, due to internal rearrangement of Earth’s mass and external gravitational forces primarily from the Moon and Sun). Synodic Day Noon to noon = synodic or solar day (point 1 to 3). This is not the time for one complete spin of Earth (1 to 2). Because Earth also orbits at the same time as it is spinning, it takes a little extra time for the Sun to come back to noon after one complete spin. Because the orbit is elliptical, when Earth is closest to the Sun it is moving faster, and it takes longer to bring the Sun back around to noon. When Earth is farther it moves slower and it takes less time to rotate the Sun back to noon. Mean Solar Day is an average of the amount time it takes to go from noon to noon throughout an orbit = 24 Hours Real solar day varies by up to 30 seconds depending on the time of year. -

Common Era Sea-Level Budgets Along the U.S. Atlantic Coast ✉ Jennifer S

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22079-2 OPEN Common Era sea-level budgets along the U.S. Atlantic coast ✉ Jennifer S. Walker 1,2 , Robert E. Kopp 1,2, Timothy A. Shaw 3, Niamh Cahill 4, Nicole S. Khan5, Donald C. Barber 6, Erica L. Ashe 1,2, Matthew J. Brain7, Jennifer L. Clear8, D. Reide Corbett 9 & Benjamin P. Horton 3,10 Sea-level budgets account for the contributions of processes driving sea-level change, but are 1234567890():,; predominantly focused on global-mean sea level and limited to the 20th and 21st centuries. Here we estimate site-specific sea-level budgets along the U.S. Atlantic coast during the Common Era (0–2000 CE) by separating relative sea-level (RSL) records into process- related signals on different spatial scales. Regional-scale, temporally linear processes driven by glacial isostatic adjustment dominate RSL change and exhibit a spatial gradient, with fastest rates of rise in southern New Jersey (1.6 ± 0.02 mm yr−1). Regional and local, temporally non-linear processes, such as ocean/atmosphere dynamics and groundwater withdrawal, contributed between −0.3 and 0.4 mm yr−1 over centennial timescales. The most significant change in the budgets is the increasing influence of the common global signal due to ice melt and thermal expansion since 1800 CE, which became a dominant contributor to RSL with a 20th century rate of 1.3 ± 0.1 mm yr−1. 1 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. 2 Rutgers Institute of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. -

Web: © the Author(S) 2015 DOI: 10.1177/2056305115621935 Reconfiguring Social Logics and Historical Sms.Sagepub.Com Boundaries

SMSXXX10.1177/2056305115621935Social Media + SocietyAnkerson 621935research-article2015 SI: Social Media Public Space Social Media + Society July-December 2015: 1 –12 Social Media and the “Read-Only” Web: © The Author(s) 2015 DOI: 10.1177/2056305115621935 Reconfiguring Social Logics and Historical sms.sagepub.com Boundaries Megan Sapnar Ankerson Abstract The web’s historical periodization as Web 1.0 (“read-only”) and Web 2.0 (“read/write”) eras continues to hold sway even as the umbrella term “social media” has become the preferred way to talk about today’s ecosystem of connective media. Yet, we have much to gain by not exclusively positing social media platforms as a 21st-century phenomenon. Through case studies of two commercially sponsored web projects from the mid-1990s—Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab’s Day in the Life of Cyberspace and Rick Smolan’s 24 Hours in Cyberspace—this article examines how notions of social and publics were imagined and designed into the web at the start of the dot-com boom. In lieu of a discourse of versions, I draw on Lucy Suchman’s trope of configuration as an analytic tool for rethinking web historiography. By tracing how cultural imaginaries of the Internet as a public space are conjoined with technological artifacts (content management systems, templates, session tracking, and e-commerce platforms) and reconfigured over time, the discourses of “read-only publishing” and the “social media revolution” can be reframed not as exclusively oppositional logics, but rather, as mutually informing the design and development of today’s social, commercial, web. Keywords social media, web history, web 1.0, web 2.0, public, read-only For a decade now, the participatory potential of social media Yet, a closer examination of web history suggests the has become synonymous with Web 2.0 platforms like boundaries separating 1.0 and 2.0 eras may do more to dis- Facebook and Twitter that facilitate the sharing of user-gen- tort our understandings of cultural and technological change. -

A School-Wide Effort for Learning History Via a Time Capsule

Social Education 71(5), pp 261–266, 271 ©2007 National Council for the Social Studies Elementary Education A School-Wide Effort for Learning History via a Time Capsule C. Glennon Rowell, M. Gail Hickey, Kendall Gecsei, and Stacy Klein The time is early fall of 2004. For thousands of elementary school students of “memory books” that have been cre- throughout the country, routines for beginning a new school year are similar. Students ated by students through the years? are getting to know their teachers and anticipating the activities ahead in subjects from As in any school-wide project, interest reading to social studies. They are getting acquainted with new content area books grows daily; the entire school popula- and materials and new media center library books. And across the nation, students tion is focused on one event—closing are catching up with classmates they have not seen during the summer months and down the older building and moving to getting acquainted with new classmates. a newer one. And in this context, in the fall of 2004, students, teachers, admin- For the 370 students in kindergar- the 10 principals who have served the istrators, and staff respond to a unique ten through fifth grade at Ridgedale school since its opening in 1954. call to develop a time capsule that (1) Elementary School in Knoxville, The current principal is puzzling gives a history of Ridgedale Elementary Tennessee, there is a special buzz in the over what she should say in a letter that School (1954–2005) and (2) reflects the air that makes this school year unique. -

The Unexpected Value of Rediscovery

PSSXXX10.1177/0956797614542274Zhang et al.Unexpected Value of Rediscovery 542274research-article2014 Research Article Psychological Science 2014, Vol. 25(10) 1851 –1860 A “Present” for the Future: The Unexpected © The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Value of Rediscovery DOI: 10.1177/0956797614542274 pss.sagepub.com Ting Zhang, Tami Kim, Alison Wood Brooks, Francesca Gino, and Michael I. Norton Harvard Business School, Harvard University Abstract Although documenting everyday activities may seem trivial, four studies reveal that creating records of the present generates unexpected benefits by allowing future rediscoveries. In Study 1, we used a time-capsule paradigm to show that individuals underestimate the extent to which rediscovering experiences from the past will be curiosity provoking and interesting in the future. In Studies 2 and 3, we found that people are particularly likely to underestimate the pleasure of rediscovering ordinary, mundane experiences, as opposed to extraordinary experiences. Finally, Study 4 demonstrates that underestimating the pleasure of rediscovery leads to time-inconsistent choices: Individuals forgo opportunities to document the present but then prefer rediscovering those moments in the future to engaging in an alternative fun activity. Underestimating the value of rediscovery is linked to people’s erroneous faith in their memory of everyday events. By documenting the present, people provide themselves with the opportunity to rediscover mundane moments that may otherwise have been forgotten. Keywords affective forecasting, curiosity, interest, memory, rediscovery, open data, open materials Received 2/3/14; Revision accepted 6/7/14 At any moment, individuals can choose to capture their estimating the emotional impact of both negative and current experiences—for example, by taking photo- positive events in the future (Frederick & Loewenstein, graphs or writing diary entries—or to let those moments 1999; Fredrickson & Kahneman, 1993; Gilbert, elapse undocumented. -

4Th Grade Social Studies Curriculum Resource Guide

VISIT INDIANA: 4 th GRADE SOCIAL STUDIES Presented by Indiana Office of Tourism Development ©2014 1 VISIT INDIANA: 4 th GRADE SOCIAL STUDIES Dear Indiana Educator: It is my great pleasure to present our Visit Indiana: 4th Grade Social Studies Curriculum resource guide. Created for teachers by teachers in accordance with the Indiana Academic Standards, this resource guide provides the tools you’ll need to connect your students with Indiana’s history through the lens of travel and tourism. Built on Problem-Based Learning methodology, students will develop flexible knowledge, effective problem-solving skills, self-directed learning and effective collaboration skills as they explore Indiana, its history and allure. This resource guide has been officially endorsed by the Indiana Bicentennial Commission and will challenge students to: Work in teams Research geography Examine climate and weather patterns Solve mathematical questions related to travel Comprehend economic patterns Learn about the historical significance of Indiana places, people and events of interest Thank you for choosing to use our Visit Indiana: 4th Grade Social Studies Curriculum resource. I hope you find it as enjoyable to teach as we did to create. For more information and online resources, go to www.visitindianateachers.com. Best regards, Mark Newman Executive Director Indiana Office of Tourism Development 1 North Capitol Avenue, Suite 600 Indianapolis, IN 46204 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Project Overview .............................................................................................. -

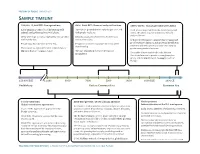

Answer Key Sample Timeline

HISTORY OF FOOD | ANSWER KEY SAMPLE TIMELINE 150,000–11,000 BCE: Pre-agriculture 6000–3000 BCE: Dawn of early civilizations 1600s–1800s: Global agricultural evolution Early humans acquired food by hunting wild Agriculture provided more calories per acre and Food plants imported from the Americas spread animals and gathering from wild plants. tied people to places. across the globe; improved nutrition helped Diets were high in fruits, vegetables, lean protein Densely populated settlements evolved into reduce disease. and healthy fats. towns, then cities. Refrigerated transport, improved processing and preservation techniques and growing distribution People may have lived into their 70s. People become free to pursue interests other than farming. networks allowed farmers to ship their surplus There were no signs of the diet-related chronic goods over greater distances. illnesses that are common today. The rise of political elites created social inequalities. Favorable climate and fertile soils allowed American farmers to produce enough surplus grain, and eventually meat, to supply much of Europe. 150 ,000 BCE 11 ,000 9000 7000 5000 3000 1000 BCE 1000 CE Prehistory Before Common Era Common Era 11,000–5000 BCE: 6000 BCE–present: Cycles of boom and bust 1800s–present: Global transition to agriculture Industrialization of the U.S. food system Increases in food production competed against population 11,000 BCE: Agriculture appeared in the growth, resource degradation, changing climate, droughts, Early 1900s: Synthetic fertilizer was invented. Fertile Crescent. and other drivers of famine. Farmers became more dependent on chemical 6000 BCE: Most farm animals had become The decline of Sumer, Greece, Rome and other ancient and fossil fuel inputs. -

Dionysius Exiguus Name: Date

Name: Date: Numbering Years Ancient calendars were generally based on the calendar, this is AD 622. Most of 2013 is part of the beginning of a ruler's reign. For example, a certain Islamic year AH1434. AH is a Latin phrase that can year would be identified as the third be translated as “the year of the journey.” year of Hammurabi’s rule. The Hebrew calendar is used for Jewish religious Most people today use the services. The Hebrew year 5774 began at sunset on Western calendar (also known as September 4, 2013. Years are marked AM on the the Gregorian calendar) for Hebrew calendar for a Latin phrase that means “the everyday purposes. About AD525, beginning of the world.” a Christian monk named Dionysius Exiguus The Chinese calendar is used for festivals and marked the year Christ was born as 1. The Western holidays in many East Asian nations. In the Chinese calendar tells us we live in 2013, which is sometimes calendar, most of 2013 is known as the Year of the written AD 2013. AD refers to the anno Domini, a Snake. Latin phrase that means “the year of the Lord.” On Western calendars there are ten years in a The years before the birth of Christ are numbered decade, one hundred years in a century, and one backward from his birth. The year before AD 1 was 1 thousand years in a millennium. This is considered BC, or one year “before Christ.” the twenty-first century of the When referring to dates before Dionysius Exiguus Common Era. -

10, 2016, Phoenix, Arizona, USA 1 Millennial Time Capsules As A

WM2016 Conference, March 6 – 10, 2016, Phoenix, Arizona, USA Millennial Time Capsules as a Promising Means for Preserving Records for Future Generations-16542 Claudio Pescatore* and Abraham Van Luik** *Private Practice Consultant, 72 Rue de la République, 92190 Meudon, France, [email protected] **U.S. Department of Energy, 4120 South National Parks Highway, Carlsbad, New Mexico 88220, USA, [email protected] ABSTRACT When we deal with preservation of Records, Knowledge and Memory (RK&M) for any long-term, non-inspected facility such a deep geological repository, there is no single technical or cultural provision that can be relied upon to do alone the preservation job 100%. Rather we should increase our chances by implementing a combination of approaches based on different components that provide redundancy and/or pointers to one another. Time capsules are no exception. However, they seem well suited to support national archives and other preservation elements, in order to preserve RK&M as long as possible or interesting. Time capsules are a ready to go, workable concept, with many examples of implementation of large-size, millennial time capsules at small depths based on science and lessons to be learned. A proposal is also made for considering and developing small-size time capsules placed strategically deep underground at repository level. INTRODUCTION Time capsules are used rather commonly by schools, companies, councils and even families to record and preserve today's artefacts for future generations, documenting how we live today. The practice is rather widespread and it suffices to search “time capsule” on the Internet. Numerous examples exist in the USA, Japan and Europe of millennial time capsules at small depths based on a scientific approach and with many lessons learned.