1 Philosophical Perspectives on Evolutionary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Kinds and Concepts: a Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account

Natural Kinds and Concepts: A Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account Ingo Brigandt Abstract: In this chapter I lay out a notion of philosophical naturalism that aligns with prag- matism. It is developed and illustrated by a presentation of my views on natural kinds and my theory of concepts. Both accounts reflect a methodological naturalism and are defended not by way of metaphysical considerations, but in terms of their philosophical fruitfulness. A core theme is that the epistemic interests of scientists have to be taken into account by any natural- istic philosophy of science in general, and any account of natural kinds and scientific concepts in particular. I conclude with general methodological remarks on how to develop and defend philosophical notions without using intuitions. The central aim of this essay is to put forward a notion of naturalism that broadly aligns with pragmatism. I do so by outlining my views on natural kinds and my account of concepts, which I have defended in recent publications (Brigandt, 2009, 2010b). Philosophical accounts of both natural kinds and con- cepts are usually taken to be metaphysical endeavours, which attempt to develop a theory of the nature of natural kinds (as objectively existing entities of the world) or of the nature of concepts (as objectively existing mental entities). However, I shall argue that any account of natural kinds or concepts must an- swer to epistemological questions as well and will offer a simultaneously prag- matist and naturalistic defence of my views on natural kinds and concepts. Many philosophers conceive of naturalism as a primarily metaphysical doc- trine, such as a commitment to a physicalist ontology or the idea that humans and their intellectual and moral capacities are a part of nature. -

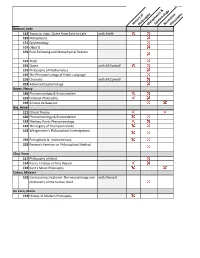

History of Philosophymetaphysics & Epistem Ology Norm Ative

HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Azzouni, Jody 114 Topics in Logic: Quine from Early to Late with Smith 120 Metaphysics 131 Epistemology 191 Objects 191 Rule-Following and Metaphysical Realism 191 Truth 191 Quine with McConnell 191 Philosophy of Mathematics 192 The Phenomenology of Public Language 195 Chomsky with McConnell 292 Advanced Epistemology Bauer, Nancy 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 191 Feminist Philosophy 192 Simone de Beauvoir Baz, Avner 121 Ethical Theory 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 192 Merleau Ponty Phenomenology 192 The Legacy of Thompson Clarke 192 Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations 292 Perceptions & Indeterminacy 292 Research Seminar on Philosophical Method Choi, Yoon 117 Philosophy of Mind 164 Kant's Critique of Pure Reason 192 Kant's Moral Philosophy Cohen, Michael 192 Conciousness Explored: The neurobiology and with Dennett philosophy of the human mind De Caro, Mario 152 History of Modern Philosophy De HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Car 191 Nature & Norms 191 Free Will & Moral Responsibility Denby, David 133 Philosophy of Language 152 History of Modern Philosophy 191 History of Analytic Philosophy 191 Topics in Metaphysics 195 The Philosophy of David Lewis Dennett, Dan 191 Foundations of Cognitive Science 192 Artificial Agents & Autonomy with Scheutz 192 Cultural Evolution-Is it Darwinian 192 Topics in Philosophy of Biology: The Boundaries with Forber of Darwinian Theory 192 Evolving Minds: From Bacteria to Bach 192 Conciousness -

Development, Evolution, and Adaptation Author(S): Kim Sterelny Source: Philosophy of Science, Vol

Philosophy of Science Association Development, Evolution, and Adaptation Author(s): Kim Sterelny Source: Philosophy of Science, Vol. 67, Supplement. Proceedings of the 1998 Biennial Meetings of the Philosophy of Science Association. Part II: Symposia Papers (Sep., 2000), pp. S369-S387 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Philosophy of Science Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/188681 Accessed: 03/03/2010 17:09 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Philosophy of Science Association and The University of Chicago Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Philosophy of Science. -

Foucault's Darwinian Genealogy

genealogy Article Foucault’s Darwinian Genealogy Marco Solinas Political Philosophy, University of Florence and Deutsches Institut Florenz, Via dei Pecori 1, 50123 Florence, Italy; [email protected] Academic Editor: Philip Kretsedemas Received: 10 March 2017; Accepted: 16 May 2017; Published: 23 May 2017 Abstract: This paper outlines Darwin’s theory of descent with modification in order to show that it is genealogical in a narrow sense, and that from this point of view, it can be understood as one of the basic models and sources—also indirectly via Nietzsche—of Foucault’s conception of genealogy. Therefore, this essay aims to overcome the impression of a strong opposition to Darwin that arises from Foucault’s critique of the “evolutionistic” research of “origin”—understood as Ursprung and not as Entstehung. By highlighting Darwin’s interpretation of the principles of extinction, divergence of character, and of the many complex contingencies and slight modifications in the becoming of species, this essay shows how his genealogical framework demonstrates an affinity, even if only partially, with Foucault’s genealogy. Keywords: Darwin; Foucault; genealogy; natural genealogies; teleology; evolution; extinction; origin; Entstehung; rudimentary organs “Our classifications will come to be, as far as they can be so made, genealogies; and will then truly give what may be called the plan of creation. The rules for classifying will no doubt become simpler when we have a definite object in view. We possess no pedigrees or armorial bearings; and we have to discover and trace the many diverging lines of descent in our natural genealogies, by characters of any kind which have long been inherited. -

Philosophical Perspectives on Evolutionary Theory

Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 92: 461–464, 2009 Philosophical perspectives on Evolutionary Theory A Tapper Centre for Applied Ethics & Philosophy, Curtin University of Technology, Bentley, WA [email protected] Manuscript received December 2009; accepted February 2010 Abstract Discussion of Darwinian evolutionary theory by philosophers has gone through a number of historical phases, from indifference (in the first hundred years), to criticism (in the 1960s and 70s), to enthusiasm and expansionism (since about 1980). This paper documents these phases and speculates about what, philosophically speaking, underlies them. It concludes with some comments on the present state of the evolutionary debate, where rapid and important changes within evolutionary theory may be passing by unnoticed by philosophers. Keywords: Darwinism, evolutionary theory, philosophy of biology; evolution. Introduction author. Biologists such as Richard Dawkins, Stephen Jay Gould, Steve Jones and Simon Conway Morris are Darwin once said that he had no aptitude for prominent. So also are historians of science, such as Peter philosophy: “My power to follow a long and purely Bowler, Janet Browne, Adrian Desmond and James R. abstract train of thought is very limited; I should, Moore. Equally likely, however, one might be introduced moreover, never have succeeded with metaphysics or to evolutionary theory by a philosopher of biology, for mathematics” (Darwin 1958). This was not false modesty; example Michael Ruse, David Hull or Kim Sterelny. (For -

Evolutionary Epistemology in James' Pragmatism J

35 THE ORIGIN OF AN INQUIRY: EVOLUTIONARY EPISTEMOLOGY IN JAMES' PRAGMATISM J. Ellis Perry IV University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth "Much struck." That was Darwin's way of saying that something he observed fascinated him, arrested his attention, surprised or puzzled him. The words "much struck" riddle the pages of bothhis Voyage ofthe Beagle and his The Origin of Species, and their appearance should alert the reader that Darwin was saying something important. Most of the time, the reader caninfer that something Darwin had observed was at variance with what he had expected, and that his fai th in some alleged law or general principle hadbeen shaken, and this happened repeat edly throughout his five year sojourn on the H.M.S. Beagle. The "irritation" of his doubting the theretofore necessary truths of natu ral history was Darwin's stimulus to inquiry, to creative and thor oughly original abductions. "The influence of Darwinupon philosophy resides inhis ha ving conquered the phenomena of life for the principle of transi tion, and thereby freed the new logic for application to mind and morals and life" (Dewey p. 1). While it would be an odd fellow who would disagree with the claim of Dewey and others that the American pragmatist philosophers were to no small extent influenced by the Darwinian corpus,! few have been willing to make the case for Darwin's influence on the pragmatic philosophy of William James. Philip Wiener, in his well known work, reports that Thanks to Professor Perry's remarks in his definitive work on James, "the influence of Darwin was both early and profound, and its effects crop up in unex pected quarters." Perry is a senior at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmoltth. -

Our Knowledge of the External World As a Field for Scientific Method In

Our Knowledge of the External World as a Field for Scientific Method in Philosophy By Bertrand Russell 1 PREFACE The following lectures[1] are an attempt to show, by means of examples, the nature, capacity, and limitations of the logical-analytic method in philosophy. This method, of which the first complete example is to be found in the writings of Frege, has gradually, in the course of actual research, increasingly forced itself upon me as something perfectly definite, capable of embodiment in maxims, and adequate, in all branches of philosophy, to yield whatever objective scientific knowledge it is possible to obtain. Most of the methods hitherto practised have professed to lead to more ambitious results than any that logical analysis can claim to reach, but unfortunately these results have always been such as many competent philosophers considered inadmissible. Regarded merely as hypotheses and as aids to imagination, the great systems of the past serve a very useful purpose, and are abundantly worthy of study. But something different is required if philosophy is to become a science, and to aim at results independent of the tastes and temperament of the philosopher who advocates them. In what follows, I have endeavoured to show, however imperfectly, the way by which I believe that this desideratum is to be found. [1] Delivered as Lowell Lectures in Boston, in March and April 1914. The central problem by which I have sought to illustrate method is the problem of the relation between the crude data of sense and the space, 2 time, and matter of mathematical physics. -

Darwin in the Press: What the Spanish Dailies Said About the 200Th Anniversary of Charles Darwin’S Birth

CONTRIBUTIONS to SCIENCE, 5 (2): 193–198 (2009) Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Barcelona Celebration of the Darwin Year 2009 DOI: 10.2436/20.7010.01.75 ISSN: 1575-6343 www.cat-science.cat Darwin in the press: What the Spanish dailies said about the 200th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s birth Esther Díez, Anna Mateu, Martí Domínguez Mètode, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain Resum. El bicentenari del naixement de Charles Darwin, cele- Summary. The bicentenary of Charles Darwin’s birth, cele- brat durant el passat any 2009, va provocar un considerable brated in 2009, caused a surge in the interest shown by the augment de l’interés informatiu de la figura del naturalista an- press in the life and work of the renowned English naturalist. glès. En aquest article s’analitza la cobertura informativa This article analyzes the press coverage devoted to the Darwin d’aquest aniversari en onze diaris generalistes espanyols, i Year in eleven Spanish daily papers during the week of Dar- s’estableix grosso modo quines són les principals postures de win’s birthday and provides a brief synopsis of the positions la premsa espanyola davant de la teoria de l’evolució. D’aques- adopted by the Spanish press regarding the theory of evolu- ta anàlisi, queda ben palès com el creacionisme és encara molt tion. The analysis makes very clear the relatively strong support viu en els mitjans espanyols més conservadors. for creationism by the conservative press in Spain. Paraules clau: Charles Darwin ∙ ciència vs. creacionisme ∙ Keywords: Charles Darwin ∙ science vs. creationism ∙ tractament informatiu científic scientific news coverage “The more we know of the fixed laws of nature the more In this article, we examine to what extent and in what form incredible do miracles become.” this controversy persists in Spanish society, focusing on the print media’s response to the celebration, in 2009, of the 200th Charles Darwin (1887). -

Michael N Dawson

M. N Dawson CV page 1 of 40 CURRICULUM VITAE — MICHAEL N DAWSON University of California, Merced 5200 North Lake Road, Merced, CA 95343, USA [email protected] / [email protected] CONTENTS PAGE EDUCATION 2 RESEARCH APPOINTMENTS 2 Research Positions, Field Research Experience PUBLICATIONS 3 Journal Articles (71), Book Chapters (9), Book Reviews (3), Correspondence & Commentaries (5), Editorials (11), Technical Reports & Information Booklets (5), Popular Articles (3), Submitted Articles (2), Internet resources & Videos (9) AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS 13 RESEARCH GRANTS 15 INVITED SEMINARS 19 SYMPOSIUM AND WORKSHOP ORGANIZATION 22 WORKING GROUPS 23 WORKSHOPS & TRAINING 23 CONFERENCE PRESENTATIONS 24 Plenary / Keynote, Invited, Oral, Poster TEACHING EXPERIENCE 29 Teaching Positions, Guest Lectures, Seminar Organization, Course Development, Professional Development, Postdoctoral scholars mentored, Student Supervision, Educational Outreach SERVICE 35 Centre / Graduate Groups / School, UC Merced, University of California, National, International, Consulting PROFESSIONAL MEMBERSHIPS 40 M. N Dawson CV page 2 of 40 EDUCATION back to index page 2000 Ph.D., Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, USA. Thesis: “Molecular variation and evolution in coastal marine taxa.” 1994 M.Sc., Biological Computation, University of York, England. Thesis: “REEFISH: modelling coral reef fisheries.” 1993 B.Sc., Marine Biology, University of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, England. Thesis: “Hylleberg’s concept of ‘gardening’ and the nutrition of Arenicola marina (Linné).” RESEARCH APPOINTMENTS back to index page Research Positions July 17 – Present Full Professor, University of California, Merced. July 12 – Jun 17 Associate Professor, University of California, Merced. Oct 06 – Jun 12 Assistant Professor, University of California, Merced. Mar 05 – Sep 06 Post-doctoral Researcher, w/ R. K. Grosberg, University of California, Davis. -

Evolutionism and Holism: Two Different Paradigms for the Phenomenon of Biological Evolution

R. Fondi, International Journal of Ecodynamics. Vol. 1, No. 3 (2006) 284–297 EVOLUTIONISM AND HOLISM: TWO DIFFERENT PARADIGMS FOR THE PHENOMENON OF BIOLOGICAL EVOLUTION R. FONDI Department of Earth Sciences, University of Siena, Italy. ABSTRACT The evolutionistic paradigm – the assumption that biological evolution consists in a mere process of ‘descendance with modification from common ancestors’, canonically represented by means of the phylogenetic tree model – can be seen as strictly connected to the classical or deterministic vision of the world, which dominated the 18th and 19th centuries. Research findings in palaeontology, however, have never fully supported the above- mentioned model. Besides, during the 20th century, the conceptual transformations produced by restricted and general relativity, quantum mechanics, cosmology, information theory, research into consciousness, chaos– complexity theory, evolutionary thermodynamics and biosemiotics have radically changed the scientific picture of reality. It is therefore necessary to adopt a more suitable and up-to-date paradigm, according to which nature is not seen anymore as a mere assembly of independent things, subject to the Lamarckian-Darwinian dialectics of ‘chance and necessity’, but as: (1) an extremely complex system with all its parts dynamically coordinated; (2) the evolution of which does not obey the logic of a deterministic linear continuity but that of an indeterministic global discontinuity; and (3) in which the mind or psychic dimension, particularly evident in semiotic aspects of the biological world, is an essential and indissoluble part. On the basis of its characteristics, the new paradigm can be generically named holistic, organicistic or systemic. Keywords: biological evolution, biostratigraphy, evolutionism, holism, palaeontology, systema naturae, taxa. -

PRAGMATISM AS a PHILOSOPHY of ACTION (Paper Presented at the First Nordic Pragmatism Conference, Helsinki, Finland, June 2008)

1 PRAGMATISM AS A PHILOSOPHY OF ACTION (Paper presented at the First Nordic Pragmatism Conference, Helsinki, Finland, June 2008) Erkki Kilpinen University of Helsinki When I gave the doctrine of pragmatism the name it bears, – and a doctrine of vital significance it is, – I derived the name by which I christened it from pragma, – behaviour – in order that it should be understood that the doctrine is that the only real significance of a general term lies in the general behaviour which it implies. Charles S. Peirce, May 1912 cited by Eisele (1987:95).1 Introduction: Action ahead of knowledge on pragmatism’s philosophical agenda Although the very founder of the pragmatic movement is adamant that this philosophy is inherently related to action – or behaviour as Peirce laconically says here – philosophers have been curiously reluctant to recognize this. Of course one finds in the literature comments about how pragmatists often talk about action, and some commentators feel that they talk about it too often, at the expense of traditional philosophical problems. To see this is not yet, however, to see the essential pragmatist point; in what sense they talk about action. Their usage of this term and the underlying idea differ from what is customary in other philosophical approaches. Pragmatism namely approaches all theoretical and philosophical problems as problems that in final analysis are related to action. In mainstream philosophy, both in its positivist-analytic and phenomenological versions, action is a contingent empirical phenomenon demanding an explanation. In pragmatism, action is a universal phenomenon which in itself begs no explanation but rather makes the starting point for explanations. -

The Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85128-2 - The Cambridge Companion to the Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L. Hull and Michael Ruse Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to THE PHILOSOPHY OF BIOLOGY The philosophy of biology is one of the most exciting new areas in the field of philosophy and one that is attracting much attention from working scientists. This Companion, edited by two of the founders of the field, includes newly commissioned essays by senior scholars and by up-and- coming younger scholars who collectively examine the main areas of the subject – the nature of evolutionary theory, classification, teleology and function, ecology, and the prob- lematic relationship between biology and religion, among other topics. Up-to-date and comprehensive in its coverage, this unique volume will be of interest not only to professional philosophers but also to students in the humanities and researchers in the life sciences and related areas of inquiry. David L. Hull is an emeritus professor of philosophy at Northwestern University. The author of numerous books and articles on topics in systematics, evolutionary theory, philosophy of biology, and naturalized epistemology, he is a recipient of a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship and is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Michael Ruse is professor of philosophy at Florida State University. He is the author of many books on evolutionary biology, including Can a Darwinian Be a Christian? and Darwinism and Its Discontents, both published by Cam- bridge University Press. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, he has appeared on television and radio, and he contributes regularly to popular media such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Playboy magazine.