Restoration of Motion Picture Film Editors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Blink of an Eye Why

Why Do Cuts Work? ell, the fact is that Apocalypse Now, as well as W every other theatrical film (except perhaps Hitchcock's Rope 3 ), is made up of many different pieces of film joined together into a mosaic of im ages. The mysterious part of it, though, is that the joining of those pieces-the "cut" in American termi nology 4-actually does seem to work, even though it represents a total and instantaneous displacement of one field of vision with another, a displacement that sometimes also entails a jump forward or backward in time as well as space. It works; but it could easily have been otherwise, since nothing in our day-to-day experience seems to prepare us for such a thing. Instead, from the moment we get up in the morning until we close our eyes at night, the visual reality we perceive is a continuous 3 A film composed of only ten shots, each ten minutes long, invis ibly joined together, so that the impression is of a complete lack of editing. 4 I was aware, talking to an Australian audience, of the bias inherent in our respective languages. In the States, film is "cut," which puts the emphasis on separation. In Australia (and in Great Britain), film is "joined," with the emphasis on bringing together. 5 6 IN THE BLINK OF AN EYE WHY stream of linked images: In fact, for millions of years context: The displacement of tl tens, hundreds of millions of years-life on Earth has motion nor change of context, ; experienced the world this way. -

CINERAMA: the First Really Big Show

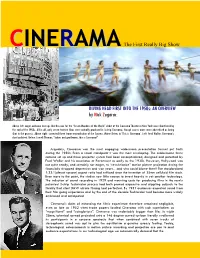

CCINEN RRAMAM : The First Really Big Show DIVING HEAD FIRST INTO THE 1950s:: AN OVERVIEW by Nick Zegarac Above left: eager audience line ups like this one for the “Seven Wonders of the World” debut at the Cinerama Theater in New York were short lived by the end of the 1950s. All in all, only seven feature films were actually produced in 3-strip Cinerama, though scores more were advertised as being shot in the process. Above right: corrected three frame reproduction of the Cypress Water Skiers in ‘This is Cinerama’. Left: Fred Waller, Cinerama’s chief architect. Below: Lowell Thomas; “ladies and gentlemen, this is Cinerama!” Arguably, Cinerama was the most engaging widescreen presentation format put forth during the 1950s. From a visual standpoint it was the most enveloping. The cumbersome three camera set up and three projector system had been conceptualized, designed and patented by Fred Waller and his associates at Paramount as early as the 1930s. However, Hollywood was not quite ready, and certainly not eager, to “revolutionize” motion picture projection during the financially strapped depression and war years…and who could blame them? The standardized 1:33:1(almost square) aspect ratio had sufficed since the invention of 35mm celluloid film stock. Even more to the point, the studios saw little reason to invest heavily in yet another technology. The induction of sound recording in 1929 and mounting costs for producing films in the newly patented 3-strip Technicolor process had both proved expensive and crippling adjuncts to the fluidity that silent B&W nitrate filming had perfected. -

Runaway Production Problem? the Phenomenon of “Runaway” Film and Television Production from the U.S

U.S. RUNAWAY FILM AND TELEVISION PRODUCTION STUDY REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary Page 2 II. The U.S. Runaway Film and Television Production Problem – A. Runaway Activity/Trends Page 6 – B. Total Economic Impact Page 11 – C. U.S. Regional Impact Page 15 – D. Direct Labor Impact Page 16 – E. Future Impact Page 17 III. The Causes – A. Production Location Decision Drivers Page 18 – B. Exchange Rates and Factor Costs Page 19 – C. Foreign Tax Incentives Page 20 – D. Total Cost Differences Page 23 – E. Foreign Infrastructure Page 23 – F. The Integrated Approach and Canada Page 24 IV. Study Methodology and Key Terms Page 27 V. About Monitor Company Page 29 1 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY “economic” runaways. Note that the study’s scope included theatrical films, films for television, Background television mini-series, and thirty and sixty minute television series. Other types of productions such as In January 1999, the Directors Guild of America commercials, and news and sports programming (DGA) and Screen Actors Guild (SAG) retained were not included. Monitor Company, a leading management consulting firm, to conduct an investigation into What Is The U.S. Runaway Production Problem? the phenomenon of “runaway” film and television production from the U.S. The Guilds (on an The study results show that economic runaway film anecdotal basis) had been noting an accelerating and television productions are a persistent, growing, runaway phenomenon, and the need to create an and very significant issue for the U.S. In 1998, of objective quantitative analysis led to the study being the 1,075 U.S.-developed film and television commissioned. -

Pilot Season

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College Spring 2014 Pilot Season Kelly Cousineau Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cousineau, Kelly, "Pilot Season" (2014). University Honors Theses. Paper 43. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pilot Season by Kelly Cousineau An undergraduate honorsrequirements thesis submitted for the degree in partial of fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts in University Honors and Film Thesis Adviser William Tate Portland State University 2014 Abstract In the 1930s, two historical figures pioneered the cinematic movement into color technology and theory: Technicolor CEO Herbert Kalmus and Color Director Natalie Kalmus. Through strict licensing policies and creative branding, the husband-and-wife duo led Technicolor in the aesthetic revolution of colorizing Hollywood. However, Technicolor's enormous success, beginning in 1938 with The Wizard of Oz, followed decades of duress on the company. Studios had been reluctant to adopt color due to its high costs and Natalie's commanding presence on set represented a threat to those within the industry who demanded creative license. The discrimination that Natalie faced, while undoubtedly linked to her gender, was more systemically linked to her symbolic representation of Technicolor itself and its transformation of the industry from one based on black-and-white photography to a highly sanctioned world of color photography. -

10. the Extraordinarily Stable Technicolor Dye-Imbibition Motion

345 The Permanence and Care of Color Photographs Chapter 10 10. The Extraordinarily Stable Technicolor Dye-Imbibition Motion Picture Color Print Process (1932–1978) Except for archival showings, Gone With the He notes that the negative used to make Wind hasn’t looked good theatrically since the existing prints in circulation had worn out [faded]. last Technicolor prints were struck in 1954; the “That negative dates back to the early ’50s 1961 reissue was in crummy Eastman Color when United Artists acquired the film’s distri- (the prints faded), and 1967’s washed-out bution rights from Warner Bros. in the pur- “widescreen” version was an abomination.1 chase of the old WB library. Four years ago we at MGM/UA went back to the three-strip Tech- Mike Clark nicolor materials to make a new internegative “Movies Pretty as a Picture” and now have excellent printing materials. All USA Today – October 15, 1987 it takes is a phone call to our lab to make new prints,” he says.3 In 1939, it was the most technically sophisti- cated color film ever made, but by 1987 Gone Lawrence Cohn With the Wind looked more like Confederates “Turner Eyes ’38 Robin Hood Redux” from Mars. Scarlett and Rhett had grown green Variety – July 25, 1990 and blue, a result of unstable film stocks and generations of badly duplicated prints. Hair The 45-Year Era of “Permanent” styles and costumes, once marvels of spectral Technicolor Motion Pictures subtlety, looked as though captured in Crayola, not Technicolor. With the introduction in 1932 of the Technicolor Motion Not anymore. -

Format Factor Fundamentals (Corrections Appreciated - [email protected])

Mark Schubin's Format Factor Fundamentals (corrections appreciated - [email protected]) Dimensions in mm; figures rounded; diagonal determines lens format; AR is aspect ratio; divide comparable dimensions for format factor; lp/mm figures for dimension with highest resolution; 1920 represents lp/mm at full-HD resolution. Camera Diagonal AR :1 Width Height lp/mm 1920 Vision Research Phantom 65 59.6 5:3 1.67 51.2 30.5 40 19 Full-frame DSLR (Canon 5D) 43.3 3:2 1.5 36 24 27 Dalsa Origin, Evolution 38.1 ~2:1 1.98 34.0 17.2 60 31 NAC Memrecam fx K4 35.6 5:4 1.25 27.8 22.2 23 35 Super Hi-Vision 2.5-inch 34 16:9 1.78 29.8 16.4 129 32 Super 35 film 31.1 4:3 1.33 24.9 18.7 -- -- Weisscam HS-2 31.1 4:3 1.33 24.9 18.7 55 39 ARRI D-21 30.8 4:3 1.33 23.8 17.8 61 40 Vision Research Phantom HD 29.1 16:9 1.78 25.6 13.9 40 38 APS-C Canon 7D 28.6 ~13:8 1.64 24.4 14.9 39 APS-C Nikon, Pentax DSLR 28.4 3:2 1.5 23.6 15.8 41 Red One 28.0 16:9 1.78 24.4 13.7 93 39 Panavision Genesis 27.5 16:9 1.78 24.0 13.5 120 40 35-mm Academy aperture film 27.3 11:8 1.38 22.0 16.0 -- -- APS-C Canon DSLR 26.8 3:2 1.5 22.3 14.9 43 Photron Ultima APX-RS 24.6 1:1 1 17.4 17.4 29 55 Panasonic 4/3 DSLR 21.6 16:9 1.78 18.9 10.6 51 Weinberger Cine SpeedCam 20 ~3:2 1.55 17 11 47 56 Super Hi-Vision/4K 1.25-inch 19 16:9 1.78 16.6 9.2 231 58 Weisscam HS-1 19 5:4 1.25 15 12 43 64 1-inch 1035-line HDTV 16.0 16:9 1.78 13.9 7.8 69 69 1-inch 720-line HDTV 16.0 16:9 1.78 13.9 7.8 46 69 Super 16 film 14.5 5:3 1.67 12.5 7.4 -- -- 16-mm film 12.7 11:8 1.38 10.3 7.5 -- -- Ikonoskop a-cam dII 12.2 -

Spirit 4K® High-Performance Film Scanner with Bones and Datacine®

Product Data Sheet Spirit 4K® High-Performance Film Scanner with Bones and DataCine® Spirit 4K Film Scanner/Bones Combination Digital intermediate production – the motion picture workflow in which film is handled only once for scan- ning and then processed with a high-resolution digital clone that can be down-sampled to the appropriate out- put resolution – demands the highest resolution and the highest precision scanning. While 2K resolution is widely accepted for digital post production, there are situations when even a higher re- solution is required, such as for digital effects. As the cost of storage continues to fall and ultra-high resolu- tion display devices are introduced, 4K postproduction workflows are becoming viable and affordable. The combination of the Spirit 4K high-performance film scanner and Bones system is ahead of its time, offe- ring you the choice of 2K scanning in real time (up to 30 frames per second) and 4K scanning at up to 7.5 fps depending on the selected packing format and the receiving system’s capability. In addition, the internal spatial processor of the Spirit 4K system lets you scan in 4K and output in 2K. This oversampling mode eli- minates picture artifacts and captures the full dynamic range of film with 16-bit signal processing. And in either The Spirit 4K® from DFT Digital Film Technology is 2K or 4K scanning modes, the Spirit 4K scanner offers a high-performance, high-speed Film Scanner and unrivalled image detail, capturing that indefinable film DataCine® solution for Digital Intermediate, Commer- look to perfection. cial, Telecine, Restoration, and Archiving applications. -

FILM FORMATS ------8 Mm Film Is a Motion Picture Film Format in Which the Filmstrip Is Eight Millimeters Wide

FILM FORMATS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 8 mm film is a motion picture film format in which the filmstrip is eight millimeters wide. It exists in two main versions: regular or standard 8 mm and Super 8. There are also two other varieties of Super 8 which require different cameras but which produce a final film with the same dimensions. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Standard 8 The standard 8 mm film format was developed by the Eastman Kodak company during the Great Depression and released on the market in 1932 to create a home movie format less expensive than 16 mm. The film spools actually contain a 16 mm film with twice as many perforations along each edge than normal 16 mm film, which is only exposed along half of its width. When the film reaches its end in the takeup spool, the camera is opened and the spools in the camera are flipped and swapped (the design of the spool hole ensures that this happens properly) and the same film is exposed along the side of the film left unexposed on the first loading. During processing, the film is split down the middle, resulting in two lengths of 8 mm film, each with a single row of perforations along one edge, so fitting four times as many frames in the same amount of 16 mm film. Because the spool was reversed after filming on one side to allow filming on the other side the format was sometime called Double 8. The framesize of 8 mm is 4,8 x 3,5 mm and 1 m film contains 264 pictures. -

Cellulose Acetate Microfilm Forum

Addressing Cellulose Acetate Microfilm from a British Library Perspective The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Shenton, Helen. 2005. Addressing cellulose acetate microfilm from a British library perspective. Liber Quarterly 15(2). Published Version http://liber.library.uu.nl/publish/articles/000134/article.pdf Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3965108 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Addressing Cellulose Acetate Microfilm from a British Library perspective by HELEN SHENTON INTRODUCTION This paper is about cellulose acetate microfilm from the British Library perspective. It traces how acetate microfilm became an issue for the British Library and describes cellulose acetate deterioration. This is followed by details of what has already been done about the situation and what action is planned for the future. THE PROBLEM: CELLULOSE ACETATE DETERIORATION In order to tackle the issue it was important to be clear about what cellulose acetate deterioration is, and what can be done about it. Cellulose acetate replaced cellulose nitrate in the late 1940s and was called safety film. This was in use until the mid-1980s, when it was replaced by polyester. One definition of cellulose acetate film from the Image Permanence Institute’s Storage Guide for Acetate Film has not been bettered: “Cellulose acetate film is a modified form of cellulose, and can slowly decompose under the influence of heat, moisture and acids. -

United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 4,915,497 Loth Et Al

United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 4,915,497 Loth et al. 45 Date of Patent: Apr. 10, 1990 54 STEREOSCOPIC MOTON PICTURE (56) References Cited APPARATUS WITH HORIZONTAL FILM U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS MOVEMENT 1,324,122 12/1919 Killman ..............a saaeed seve888 352/239 2,056,600 10/1936 Crosier .................................. 352/6S (75) Inventors: Stanislaw Loth, Nanuet, N.Y.; 2,282,947 5/1942 DeSherbinin ......................... 352/60 Anthony Petitto, Los Angeles, Calif. 3,019,698 2/1962 Sheldon ........... ... 352/60 3,355,292 11/1967 White ....... ... 352/239 (73) Assignee: Parallex Company, Inc., Los 4,464,028 8/1984 Condon ................................. 352/.65 Angeles, Calif. Primary Examiner-Monroe H. Hayes Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Watson, Cole, Grindle & 21 Appl. No.: 381,300 Watson 22 Filed: Jul.18, 1989 57 ABSTRACT An apparatus for photographing a pair of diagonally (51 Int. Cl'.............................................. G03B 35/OO related left and right images of a stereoscopic image (52) U.S. C. ........................................ 352/57; 352/60; couple on to film frames of a horizontally moving 65 352/69; 352/239;352/.65 mm film having 15 film perforations per frame. 58) Field of Search ....................... 352/57, 60, 65, 69, 352/236 5 Claims, 2 Drawing Sheets U.S. Patent Apr. 10, 1990 Sheet 1 of 2 4.915,497 t Oura U.S. Patent Apr. 10, 1990 Sheet 2 of 2 4.915,497 3. z' ? - 4,915,497 1. 2 on a vertically moving film. The system includes a relay STEREOSCOP CMOTON PICTUREAPPARATUS lens which forms two vertically aligned and separated, WITH HORIZONTAL FILM MOVEMENT left and right images on the film, each image occupying approximately one vertical half of each frame area. -

Introduction

CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Introduction This book consists of edited conversations between DP’s, Gaffer’s, their crew and equipment suppliers. As such it doesn’t have the same structure as a “normal” film reference book. Our aim is to promote the free exchange of ideas among fellow professionals, the cinematographer, their camera crew, manufacturer's, rental houses and related businesses. Kodak, Arri, Aaton, Panavision, Otto Nemenz, Clairmont, Optex, VFG, Schneider, Tiffen, Fuji, Panasonic, Thomson, K5600, BandPro, Lighttools, Cooke, Plus8, SLF, Atlab and Fujinon are among the companies represented. As we have grown, we have added lists for HD, AC's, Lighting, Post etc. expanding on the original professional cinematography list started in 1996. We started with one list and 70 members in 1996, we now have, In addition to the original list aimed soley at professional cameramen, lists for assistant cameramen, docco’s, indies, video and basic cinematography. These have memberships varying from around 1,200 to over 2,500 each. These pages cover the period November 1996 to November 2001. Join us and help expand the shared knowledge:- www.cinematography.net CML – The first 5 Years…………………………. Page 1 CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Page 2 CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Introduction................................................................ 1 Shooting at 25FPS in a 60Hz Environment.............. 7 Shooting at 30 FPS................................................... 17 3D Moving Stills...................................................... -

I32-1997 the Use of Super 16 Mm Film for Television Production

EBU Technical Information I32-1997 The Use of Super 16 mm Film for Television Production EBU Committee First issued Revised Re-issued PMC 1997 Keywords: Film, 16:9 Telecines 1. Introduction This EBU Technical Information document reports on the way and extent that EBU Members and their programme suppliers use Super 16 mm film in 4:3 and 16:9 television production. A questionnaire was sent to EBU Members and other organisations involved in programme production for EBU Members. Replies were received from 36 organisations; 31 broadcasting organisations and 5 film and/or video post-production organisations. The replies showed that 26 organisations were using Super 16 mm; 22 of these were broadcasters located in Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, Greece, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. The present Technical Information document is based on the replies to the questionnaire. In a parallel exercise, the EBU has attempted to give a comparison between the costs of using Super 16 mm and 35 mm film for television production. This comparison is given in Appendix 1 2. Main Applications of Super 16 mm Film 2.1 Types of programme produced on Super 16 mm film Super 16 mm film is mainly used for single camera drama and documentary production. The final product may be intended for television release only, or, in the case of a co-production, it may be intended for both television and cinema release. 2.2 Reported advantages in the use of Super 16 mm film The reported advantages of producing in Super 16 mm film, as compared to 35 mm film, are lower costs of camera film and equipment, lower costs of film laboratory services, and a smaller technical staff needed for shooting.