Theatre Archive Project: Interview with Nick Hern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bristol Leisure Focus

Hotels Restaurants Pubs Leisure Leisure Property Specialists Investments Bristol Leisure Focus 2015 Bristol, currently European Green Capital, the first UK city to be awarded the accolade, is regularly voted as one of the best places to live in Britain, due to its eclectic and unmistakeable identity. This has led to the city being recognised as the fastest growing hi-tech sector outside of London. Large scale redevelopment of the city centre and surrounding areas and the much needed improvement of the historic waterways is presenting new opportunities and welcoming a host of new arrivals to the city. 1 The eighth largest city in the UK with a population approaching 440,000, Bristol is a vibrant and passionate city that has its own unmistakable identity. Introduction Bristol is the economic capital of the South offices and 250 residential apartments, it Once viewed as a much wasted and West, being home to more than 17,500 offers broad appeal and attracts 17 million neglected asset, Bristol’s waterfront areas businesses, with a third of UK-owned FTSE visitors each year. are benefitting from a series of large scale 100 companies having a significant presence developments bringing life to the waters’ in the city. Bristol was recently attributed as Growth continues with significant edge with schemes such as Finzels Reach the fastest growing hi-tech sector outside of developments underway to improve the and Wapping Wharf offering mixed use London (McKinsey and Co, 2014). city’s transport links. Bristol Airport is developments and waterfront leisure currently in the process of undergoing a opportunities. -

1999 + Credits

1 CARL TOMS OBE FRSA 1927 - 1999 Lorraine’ Parish Church Hall. Mansfield Nottingham Journal review 16th Dec + CREDITS: All work what & where indicated. 1950 August/ Sept - Exhibited 48 designs for + C&C – Cast & Crew details on web site of stage settings and costumes at Mansfield Art Theatricaila where there are currently 104 Gallery. Nottm Eve Post 12/08/50 and also in Nottm references to be found. Journal 12/08/50 https://theatricalia.com/person/43x/carl- toms/past 1952 + Red related notes. 52 - 59 Engaged as assistant to Oliver Messel + Film credits; http://www.filmreference.com/film/2/Carl- 1953 Toms.html#ixzz4wppJE9U2 Designer for the penthouse suite at the Dorchester Hotel. London + Television credits and other work where indicated. 1957: + Denotes local references, other work and May - Apollo de Bellac - awards. Royal Court Theatre, London, ----------------------------------------------------- 57/58 - Beth - The Apollo,Shaftesbuy Ave London C&C 1927: May 29th Born - Kirkby in Ashfield 22 Kingsway. 1958 Local Schools / Colleges: March 3 rd for one week ‘A Breath of Spring. Diamond Avenue Boys School Kirkby. Theatre Royal Nottingham. Designed by High Oakham. Mansfield. Oliver Messel. Assisted by Carl Toms. Mansfield Collage of Art. (14 years old). Programme. Review - The Stage March 6th Lived in the 1940’s with his Uncle and Aunt 58/59 - No Bed for Bacon Bristol Old Vic. who ran a grocery business on Station St C&C Kirkby. *In 1950 his home was reported as being 66 Nottingham Rd Mansfield 1959 *(Nottm Journal Aug 1950) June - The Complaisant Lover Globe Conscripted into Service joining the Royal Theatre, London. -

January 2012 at BFI Southbank

PRESS RELEASE November 2011 11/77 January 2012 at BFI Southbank Dickens on Screen, Woody Allen & the first London Comedy Film Festival Major Seasons: x Dickens on Screen Charles Dickens (1812-1870) is undoubtedly the greatest-ever English novelist, and as a key contribution to the worldwide celebrations of his 200th birthday – co-ordinated by Film London and The Charles Dickens Museum in partnership with the BFI – BFI Southbank will launch this comprehensive three-month survey of his works adapted for film and television x Wise Cracks: The Comedies of Woody Allen Woody Allen has also made his fair share of serious films, but since this month sees BFI Southbank celebrate the highlights of his peerless career as a writer-director of comedy films; with the inclusion of both Zelig (1983) and the Oscar-winning Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) on Extended Run 30 December - 19 January x Extended Run: L’Atalante (Dir, Jean Vigo, 1934) 20 January – 29 February Funny, heart-rending, erotic, suspenseful, exhilaratingly inventive... Jean Vigo’s only full- length feature satisfies on so many levels, it’s no surprise it’s widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made Featured Events Highlights from our events calendar include: x LoCo presents: The London Comedy Film Festival 26 – 29 January LoCo joins forces with BFI Southbank to present the first London Comedy Film Festival, with features previews, classics, masterclasses and special guests in celebration of the genre x Plus previews of some of the best titles from the BFI London Film Festival: -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

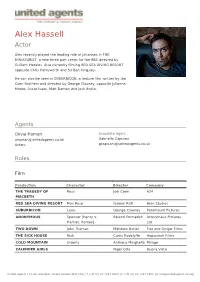

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank Production of Twelfth Night

2016 shakespeare’s globe Annual review contents Welcome 5 Theatre: The Globe 8 Theatre: The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse 14 Celebrating Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary 20 Globe Education – Inspiring Young People 30 Globe Education – Learning for All 33 Exhibition & Tour 36 Catering, Retail and Hospitality 37 Widening Engagement 38 How We Made It & How We Spent It 41 Looking Forward 42 Last Words 45 Thank You! – Our Stewards 47 Thank You! – Our Supporters 48 Who’s Who 50 The Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank production of Twelfth Night. Photo: Cesare de Giglio The Little Matchgirl and Other Happier Tales. Photo: Steve Tanner WELCOME 2016 – a momentous year – in which the world celebrated the richness of Shakespeare’s legacy 400 years after his death. Shakespeare’s Globe is proud to have played a part in those celebrations in 197 countries and led the festivities in London, where Shakespeare wrote and worked. Our Globe to Globe Hamlet tour travelled 193,000 miles before coming home for a final emotional performance in the Globe to mark the end, not just of this phenomenal worldwide journey, but the artistic handover from Dominic Dromgoole to Emma Rice. A memorable season of late Shakespeare plays in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and two outstanding Globe transfers in the West End ran concurrently with the last leg of the Globe to Globe Hamlet tour. On Shakespeare’s birthday, 23 April, we welcomed President Obama to the Globe. Actors performed scenes from the late plays running in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Southwark Cathedral, a service which was the only major civic event to mark the anniversary in London and was attended by our Patron, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. -

The Road to Bristol Old Vic

250 YEARS OLD Thank you for being part of one of the most significant anniversaries in the history of British theatre. We’ve done our best to curate a programme worthy of your efforts, inspired by the astonishing creativity of the thousands of artists – from Sarah Siddons to Sally Cookson – who have delighted and entertained you and your forebears over the last 250 years. But at heart, ours is a story of passion, survival and reinvention. All the other theatres producing plays in 1766 have fallen down or been demolished because, at some point in their history, their audiences abandoned them. This one has survived because each time it’s faced disaster, Bristolians from all over the world have given it new life. It happened in 1800, when popular demand led to the ceiling being tipped up and the new gallery being built, increasing the capacity to an eye-watering 1,600. It happened in 1933 when Blanche Rogers initiated the campaign that the old place should be saved and become ‘Bristol’s Old Vic’. It happened in 2007 when Dick Penny held the open meeting (which many of you attended), leading to the Arts Council continuing its vital support for the theatre. And it’s happening throughout this wonderful anniversary, as you carry us towards the final stage of the refurbishment that will set us securely on our adventures over the next 250 years. So as you read about the shows we’re staging and the projects we’re curating during our birthday year, don’t forget to give yourself a warm pat on the back for being the people who are, in the end, responsible for all of it. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

N.F. Simpson and “The Theatre of the Absurd”

Platform , Vol. 3, No. 1 N.F. Simpson and “The Theatre of the Absurd” Neema Parvini (Royal Holloway, University of London) In 1958, in the Observer , Kenneth Tynan wrote of “a dazzling new playwright,” with his inimitable enthusiasm he declared: “I am ready to burn my boats and promise [that] N.F. Simpson [is] the most gifted comic writer the English stage has discovered since the war” (Tynan 210). Now, in 2008, despite a recent West End revival, 1 few critics would cite Simpson at all and debates regarding the “most gifted comic writer” of the English stage would invariably be centred on Tom Stoppard, Joe Orton, Samuel Beckett or, for those with a more morose sense of humour, Harold Pinter. Part of the reason for Simpson’s critical decline can be put down to protracted periods of silence; after his run of critically and commercially successful plays with The English Stage Company, 2 Simpson only produced two further full length plays: The Cresta Run (1965) and Was He Anyone? (1972). Of these, the former was poorly received and the latter only reached the fringe theatre. 3 As Stephen Pile recently put it, “in 1983, Simpson himself vanished” with no apparent fixed address. The other reason that may be cited is that, more than any other British writer of his time, Simpson was associated with “The Theatre of the Absurd.” As the vogue for the style died out in London, Simpson’s brand of Absurdism simply went out of fashion. John Russell Taylor offers perhaps the most scathing version of that argument: “whether one likes or dislikes N.F. -

Othello and the Stranger in Shakespeare

THEATRE & TALK AN ETF BAR FRINGE PRODUCTION “Black is Fair” Othello and the Stranger in Shakespeare Teacher`s Support Pack The English Theatre Frankfurt 2013 William Shakespeare, Othello The English Theatre Frankfurt 2013 Teacher`s Support Pack Table of Contents 1 Othello, the Moor of Venice: Introduction p. 3 2 Characters p. 5 3 Synopsis p. 5 3.1 Brief Version p. 5 3.2 Comprehensive Version p. 6 4 The Main Characters as Seen by Themselves and Others p. 11 4.1 Othello p. 11 4.2 Iago p. 16 4.3 Desdemona p. 21 5 Perceptions of Blackness & The Moor p. 25 5.1 A Selection of Quotes from the Play p. 25 5.2 Definition: The word "Moor" p. 26 5.3 Essay: The Black Other in Elizabethan Drama p. 28 6 The ETF 2013 production p. 33 6.1 Time p. 33 6.2 Setting p. 34 6.3 On Jealousy p. 36 6.4 Lingering Questions Today p. 38 A Note for the Teachers (Hinweise zu diesen Unterrichtsmaterialien) Sie können dieses Teacher`s Support Pack auf Anfrage auch als Word-Dokument bekommen, um einzelne Texte/Aufgaben vor Ausdruck zu bearbeiten. Das bietet Ihnen auch die Chance, das Paket in der von Ihnen gewünschten Fassung an Ihre SchülerInnen digital weiterzuleiten. Das Bild- und Informationsmaterial kann den SchülerInnen dabei helfen, sich einen Überblick über die relevanten thematischen Aspekte zu verschaffen und eigene Sichtweisen des Stücks zu entdecken. Bei allen Fragen bezüglich dieser Materialien oder Interesse an Begleitworkshops zu einem Aufführungsbesuch für Ihre Lerngruppe Gespräche mit Schauspielern nach der Vorstellung wenden Sie sich bitte per Email an uns: [email protected] Das Team von T.I.E.S (Theatre in Education Service) wünscht Ihnen viel Erfolg bei der Arbeit mit dem Teacher`s Support Pack. -

Theatre Archive Project Archive

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 349 Title: Theatre Archive Project: Archive Scope: A collection of interviews on CD-ROM with those visiting or working in the theatre between 1945 and 1968, created by the Theatre Archive Project (British Library and De Montfort University); also copies of some correspondence Dates: 1958-2008 Level: Fonds Extent: 3 boxes Name of creator: Theatre Archive Project Administrative / biographical history: Beginning in 2003, the Theatre Archive Project is a major reinvestigation of British theatre history between 1945 and 1968, from the perspectives of both the members of the audience and those working in the theatre at the time. It encompasses both the post-war theatre archives held by the British Library, and also their post-1968 scripts collection. In addition, many oral history interviews have been carried out with visitors and theatre practitioners. The Project began at the University of Sheffield and later transferred to De Montfort University. The archive at Sheffield contains 170 CD-ROMs of interviews with theatre workers and audience members, including Glenda Jackson, Brian Rix, Susan Engel and Michael Frayn. There is also a collection of copies of correspondence between Gyorgy Lengyel and Michel and Suria Saint Denis, and between Gyorgy Lengyel and Sir John Gielgud, dating from 1958 to 1999. Related collections: De Montfort University Library Source: Deposited by Theatre Archive Project staff, 2005-2009 System of arrangement: As received Subjects: Theatre Conditions of access: Available to all researchers, by appointment Restrictions: None Copyright: According to document Finding aids: Listed MS 349 THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT: ARCHIVE 349/1 Interviews on CD-ROM (Alphabetical listing) Interviewee Abstract Interviewer Date of Interview Disc no. -

Don Pasquale

Gaetano Donizetti Don Pasquale CONDUCTOR Dramma buffo in three acts James Levine Libretto by Giovanni Ruffini and the composer PRODUCTION Otto Schenk Saturday, November 13, 2010, 1:00–3:45 pm SET & COSTUME DESIGNER Rolf Langenfass LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler This production of Don Pasquale was made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund. The revival of this production was made possible by a gift from The Dr. M. Lee Pearce Foundation. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 129th Metropolitan Opera performance of Gaetano Donizetti’s Don Pasquale Conductor James Levine in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Don Pasquale, an elderly bachelor John Del Carlo Dr. Malatesta, his physician Mariusz Kwiecien* Ernesto, Pasquale’s nephew Matthew Polenzani Norina, a youthful widow, beloved of Ernesto Anna Netrebko A Notary, Malatesta’s cousin Carlino Bernard Fitch Saturday, November 13, 2010, 1:00–3:45 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from its founding sponsor, the Neubauer Family Foundation. Bloomberg is the global corporate sponsor of The Met: Live in HD. Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera Mariusz Kwiecien as Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Dr. Malatesta and Musical Preparation Denise Massé, Joseph Colaneri, Anna Netrebko as Carrie-Ann Matheson, Carol Isaac, and Hemdi Kfir Norina in a scene Assistant Stage Directors J. Knighten Smit and from Donizetti’s Don Pasquale Kathleen Smith Belcher Prompter Carrie-Ann Matheson Met Titles Sonya Friedman Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs by Metropolitan Opera Wig Department Assistant to the costume designer Philip Heckman This performance is made possible in part by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts.