Abstract Why Song?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I. Interviews

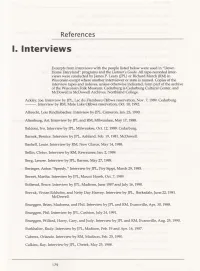

References I. Interviews Excerpts from interviews with the people listed below were used in "Down Home Dairyland" programs and the Listener's Guide. All tape-recorded inter views were conducted by James P. Leary (JPL) or Richard March (RM) in Wisconsin except where another interviewer or state is named. Copies of the interview tapes and indexes, unless otherwise indicated, form part of the archive of the Wisconsin Folk Museum. Cedarburg is Cedarburg Cultural Center, and McDowell is McDowell Archives, Northland College . Ackley, Joe. Interview by JPL, Lac du Flambeau Ojibwa reservation, Nov. 7, 1989. Cedarburg. ---. Interview by RM, Mole Lake Ojibwa reservation, Oct. 10, 1992. Albrecht, Lois Rindlisbacher. Interview by JPL, Cameron, Jan. 23, 1990. Altenburg, Art. Interview by JPL and RM, Milwaukee, May 17, 1988. Baldoni, Ivo. Interview by JPL, Milwaukee, Oct. 12, 1989. Cedarburg. Barnak, Bernice. Interview by JPL, Ashland, Feb. 19, 1981. McDowell. Bashell, Louie. Interview by RM, New Glarus, May 14, 1988. Bellin, Cletus. Interview by RM, Kewaunee, Jan. 2, 1989. Berg, Lenore. Interview by JPL, Barron, May 27, 1989. Beringer, Anton "Speedy." Interview by JPL, Poy Sippi, March 29, 1985. Bernet, Martha . Interview by JPL, Mount Horeb, Oct. 7, 1989. Hollerud, Bruce. Interview by JPL, Madison, June 1987 and July 16, 1990. Brevak, Vivian Eckholm, and Netty Day Harvey. Interview by JPL, Barksdale, June 22, 1981. McDowell. Brueggen, Brian, Madonna, and Phil. Interview by JPL and RM, Evansville, Apr. 30, 1988. Brueggen, Phil. Interview by JPL, Cashton, July 24, 1991. Brueggen, Willard, Harry, Gary, and Judy. Interview by JPL and RM, Evansville, Aug. 25, 1990. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

Transnational Finnish Mobilities: Proceedings of Finnforum XI

Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen This volume is based on a selection of papers presented at Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) the conference FinnForum XI: Transnational Finnish Mobili- ties, held in Turku, Finland, in 2016. The twelve chapters dis- cuss two key issues of our time, mobility and transnational- ism, from the perspective of Finnish migration. The volume is divided into four sections. Part I, Mobile Pasts, Finland and Beyond, brings forth how Finland’s past – often imagined TRANSNATIONAL as more sedentary than today’s mobile world – was molded by various short and long-distance mobilities that occurred FINNISH MOBILITIES: both voluntarily and involuntarily. In Part II, Transnational Influences across the Atlantic, the focus is on sociocultural PROCEEDINGS OF transnationalism of Finnish migrants in the early 20th cen- tury United States. Taken together, Parts I and II show how FINNFORUM XI mobility and transnationalism are not unique features of our FINNISH MOBILITIES TRANSNATIONAL time, as scholars tend to portray them. Even before modern communication technologies and modes of transportation, migrants moved back and forth and nurtured transnational ties in various ways. Part III, Making of Contemporary Finn- ish America, examines how Finnishness is understood and maintained in North America today, focusing on the con- cepts of symbolic ethnicity and virtual villages. Part IV, Con- temporary Finnish Mobilities, centers on Finns’ present-day emigration patterns, repatriation experiences, and citizen- ship practices, illustrating how, globally speaking, Finns are privileged in their ability to be mobile and exercise transna- tionalism. Not only is the ability to move spread very uneven- ly, so is the capability to upkeep transnational connections, be they sociocultural, economic, political, or purely symbol- ic. -

Finnish-American Music in Superiorland

Chapter 1 5 Finnish-American Music in Superiorland Program 15 Performances 1. Hugo Maki, "!tin Tiltu." 2 . Viola Turpeinen and John Rosendahl, "Viulu polkka." 3 . Leo Kauppi, "Villi ruusu." 4. Walt Johnson, "Villi ruusu ." 5. Hiski Salomaa, "Lannen lokkari." 6. Oulu Hotshots, "Sakki jarven polkka." 7. Oulu Hotshots, "Maailman Matti." 8. Bobby Aro, "Highway Number 7." 9 . Oulu Hotshots, "Raatikko." The Finnish-American Homeland rom the 1880s through the first two decades of the twentieth century, more than three hundred thousand Finns emigrated to the United States, where Fjobs could be found chiefly in mills, mines, factories, fisheries, and lumber camps . Roughly half were drawn to the Lake Superior region, settling in the western half of Michigan's Upper Peninsula, across Wisconsin's northern coun ties, and throughout northern Minnesota . When they could buy land, many scratched out an existence on small farms. These settlers and their offspring, like other newcomers to America, continued their old-country musical traditions . Hymns and social dance music were per formed in homes, but institutions that fostered music were thriving by the 1920s. Suomi Synod Lutheran churches, allied with Finland's state church, established choirs, while members of the charismatic Finnish Apostolic Lutheran Church composed new hymns and adapted American gospel songs. Temperance soci eties and socialists built halls where musical plays and social dances were com mon . Cooperative stores sold musical instruments and, eventually, phonographs and Finnish-American recordings . Meanwhile ethnic newspapers advertised and reported on musical events . The Girl Played like a Heavenly Bell Finnish-American social dance musicians and singers took particular advantage of this institutional infrastructure. -

Download Naxos Audiobooks Catalogue

Naxos AudioBooks 2004 Ten years of innovation in audiobooks CLASSIC LITERATURE on CD and cassette AUDIOBOOKS 10TH ANNIVERSARY YEAR www.naxosaudiobooks.com THE FULL CATALOGUE AVAILABLE ONLINE News • New Releases • Features • Authors Actors • Competitions • Distributors • With selected Sound Clips LIST OF CONTENTS JUNIOR CLASSICS & CHILDREN’S FAVOURITES 2 CLASSIC FICTION & A Decade of the Classics MODERN CLASSICS 11 It was Milton’s great poem, Paradise Lost, read by the English POETRY 31 classical actor Anton Lesser that set Naxos AudioBooks on its particular journey to record the great classics of Western literature. DRAMA 35 That was 10 years ago, and since then we have recorded more than 250 titles ranging from Classic Fiction for adults and juniors; poetry, NON-FICTION 40 biographies and histories which have both scholarly and literary presence; and classic drama, dominated, of course, by HISTORIES 41 Shakespeare presented by some of the leading British actors. In addition, we have recorded selections from The Bible and great BIOGRAPHY 44 epics, such as Dante’s The Divine Comedy. And we feel that our own original texts – introductions to classical PHILOSOPHY 45 music, English literature and the theatre and biographies of famous people for younger listeners – have made a special contribution to RELIGION 46 audiobook literature. These have all been recorded to the highest standards, and COLLECTIONS 47 enhanced by the use of classical music taken from the Naxos and Marco Polo catalogues. We felt from the beginning that, generally, it HISTORICAL RECORDINGS 47 was not sufficient to have just a voice reading the text, and that, as in film, music can be used imaginatively to set the period and the BOX SETS 48 atmosphere of a story. -

U2 All Along the Watchtower U2 All Because of You U2 All I Want Is You U2 Angel of Harlem U2 Bad U2 Beautiful Day U2 Desire U2 D

U/z U2 All Along The Watchtower U2 All Because of You U2 All I Want Is You U2 Angel Of Harlem U2 Bad U2 Beautiful Day U2 Desire U2 Discotheque U2 Electrical Storm U2 Elevation U2 Even Better Than The Real Thing U2 Fly U2 Ground Beneath Her Feet U2 Hands That Built America U2 Haven't Found What I'm Looking For U2 Helter Skelter U2 Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me U2 I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For U2 I Will Follow U2 In A Little While U2 In Gods Country U2 Last Night On Earth U2 Lemon U2 Mothers Of The Disappeared U2 Mysterious Ways U2 New Year's Day U2 One U2 Please U2 Pride U2 Pride In The Name Of Love U2 Sometimes You Can't Make it on Your Own U2 Staring At The Sun U2 Stay U2 Stay Forever Close U2 Stuck In A Moment U2 Sunday Bloody Sunday U2 Sweetest Thing U2 Unforgettable Fire U2 Vertigo U2 Walk On U2 When Love Comes To Town U2 Where The Streets Have No Name U2 Who's Gonna Ride Your Wild Horses U2 Wild Honey U2 With Or Without You UB40 Breakfast In Bed UB40 Can't Help Falling In Love UB40 Cherry Oh Baby UB40 Cherry Oh Baby UB40 Come Back Darling UB40 Don't Break My Heart UB40 Don't Break My Heart UB40 Earth Dies Screaming UB40 Food For Thought UB40 Here I Am (Come And Take Me) UB40 Higher Ground UB40 Homely Girl UB40 I Got You Babe UB40 If It Happens Again UB40 I'll Be Yours Tonight UB40 King UB40 Kingston Town UB40 Light My Fire UB40 Many Rivers To Cross UB40 One In Ten UB40 Rat In Mi Kitchen UB40 Red Red Wine UB40 Sing Our Own Song UB40 Swing Low Sweet Chariot UB40 Tell Me Is It True UB40 Train Is Coming UB40 Until -

HILLBILLYSUOMEA JA VERENPERINTÖÄ. Etnisen Identiteetin Rakentumisesta Jingo Viitala Vachonin (1918-2009) Kirjallisessa Ja Musiikillisessa Tuotannossa

HILLBILLYSUOMEA JA VERENPERINTÖÄ. Etnisen identiteetin rakentumisesta Jingo Viitala Vachonin (1918-2009) kirjallisessa ja musiikillisessa tuotannossa. Turun yliopisto Historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Kulttuurihistoria Pro gradu -tutkielma Jari Nikkola Marraskuu 2014 Turun yliopiston laatujärjestelmän mukaisesti tämän julkaisun alkuperäisyys on tarkastettu Turnitin OriginalityCheck -järjestelmällä. TURUN YLIOPISTO Historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos NIKKOLA, JARI: Hillbillysuomea ja verenperintöä. Etnisen identiteetin muodostumisesta Jingo Viitala Vachonin (1918-2009) kirjallisessa ja musiikillisessa tuotannossa. Tutkielma, 73 s., 1 liites. Kulttuurihistoria Marraskuu 2014 Tutkimus perehtyy toisen amerikansuomalaisen sukupolven etnisen identiteetin muutoksiin 1930-luvun pula-ajan Pohjois-Michiganissa Jingo Viitala Vachonin (os. Jenny Maria Viitala) kirjallisen ja musiikillisen tuotannon kautta. Pääpaino on Michiganin yläniemekkeen Kuparisaaren alueen suomalaisyhteisöjen elämässä ja tarinoissa. Pohjalaisille vanhemmille vuonna 1918 Michiganin Toivolan kylässä syntynyt Vachon eli nuoruuttaan Yhdysvalloissa aikana, jolloin USA rajoitti voimakkaasti uusien siirtolaisten tuloa maahan. Tämä heijastui Vachonin etnisyyteen ja identiteettiin selvästi. Mukaan tulivat yleisamerikkalaiset vaikutteet sekä vaikuttimet muilta etnisiltä ryhmiltä siirtolaisaallon Suomesta tyrehdyttyä lähes kokonaan. Voimakkaimmin muutosta rakennettiin koulussa, jossa Vachon oppi toisen pääkielensä, englannin. Uuden kielen oppimisen -

KARAOKE on Demand

KARAOKE on demand Mood Media Finland Oy Äyritie 8 D, 01510 Vantaa, FINLAND Vaihde: 010 666 2230 Helpdesk: 010 666 2233 fi.all@ moodmedia.com www.moodmedia .fi FIN=FINNKARAOKE POW=POWER KARAOKE HEA=HEAVYKARAOKE Suomalaiset TÄH=KARAOKETÄHTI KSF=KSF FES=KARAOKE FESTIVAL KAPPALE ARTISTI ID TOIM 0010 APULANTA 700001 KSF 008 (HALLAA) APULANTA 700002 KSF 1972 ANSSI KELA 700003 POW 2080-LUVULLA SANNI 702735 FIN 5 LAISKAA AURINGOSSA PIENET MIEHET 702954 FIN 506 IKKUNAA MILJOONASADE 702707 FIN A VOICE IN THE DARK TACERE 702514 HEA AALLOKKO KUTSUU GEORG MALMSTEN 700004 FIN AAMU ANSSI KELA 700005 FIN AAMU ANSSI KELA 701943 TÄH AAMU PEPE WILLBERG 700006 FIN AAMU PEPE WILLBERG 701944 TÄH AAMU AIRISTOLLA OLAVI VIRTA 700007 FIN AAMU TOI, ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN 700008 FIN AAMU TOI, ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN 701945 TÄH AAMUISIN ZEN CAFE 701946 TÄH AAMULLA RAKKAANI NÄIN LEA LAVEN 701947 TÄH AAMULLA VARHAIN KANSANLAULU 701948 TÄH AAMUN KUISKAUS STELLA 700009 POW AAMUUN ON HETKI AIKAA CHARLES PLOGMAN 700010 POW AAMUYÖ MERJA RASKI 701949 TÄH AAVA EDEA 701950 TÄH AAVERATSASTAJAT DANNY 700011 FIN ADDICTED TO YOU LAURA VOUTILAINEN 700012 FIN ADIOS AMIGO LEA LAVEN 700013 FIN AFRIKKA, SARVIKUONOJEN MAA EPPU NORMAALI 700014 POW AI AI AI JA VOI VOI VOI IRWIN GOODMAN 702920 FIN AI AI JUSSI TUIJA MARIA 700015 POW AIKA NÄYTTÄÄ JUKKA KUOPPAMÄKI 700016 FIN AIKAAN SINIKELLOJEN PAULA KOIVUNIEMI 700017 FIN AIKUINEN NAINEN PAULA KOIVUNIEMI 700018 FIN AIKUINEN NAINEN PAULA KOIVUNIEMI 700019 POW AIKUINEN NAINEN PAULA KOIVUNIEMI 701951 TÄH AILA REIJO TAIPALE 700020 FIN AINA -

Emily Dickinson Poems Commentary

Emily Dickinson was twenty on 10 December 1850. There are 5 of her poems surviving from 1850-4. Poem 1 F1 ‘Awake ye muses nine’ In Emily’s youth the feast of St Valentine was celebrated not for one day but for a whole week, during which ‘the notes flew around like snowflakes (L27),’ though one year Emily had to admit to her brother Austin that her friends and younger sister had received scores of them, but his ‘highly accomplished and gifted elderly sister (L22)’ had been entirely overlooked. She sent this Valentine in 1850 to Elbridge Bowdoin, her father’s law partner, who kept it for forty years. It describes the law of life as mating, and in lines 29-30 she suggests six possible mates for Bowdoin, modestly putting herself last as ‘she with curling hair.’ The poem shows her sense of fun and skill as a verbal entertainer. Poem 2 [not in F] ‘There is another sky’ On 7 June 1851 her brother Austin took up a teaching post in Boston. Emily writes him letter after letter, begging for replies and visits home. He has promised to come for the Autumn fair on 22 October, and on 17 October Emily writes to him (L58), saying how gloomy the weather has been in Amherst lately, with frosts on the fields and only a few lingering leaves on the trees, but adds ‘Dont think that the sky will frown so the day when you come home! She will smile and look happy, and be full of sunshine then – and even should she frown upon her child returning…’ and then she follows these words with poem 2, although in the letter they are written in prose, not verse. -

Congressional Record-House. February 25

4586 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. FEBRUARY 25, HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. Soon after entering the practice of bis chosen profession he became a member of a successful law firm of that city, and was SuNDAY, Feb1"Ua.ry 25, 19<23. one of its active members in the preparation, trial, and man agement of their cases. Mr. BURROUGHS was regarded as one The House met at 12 o'clock noon, and was called to order of our able lawyers and jurists and enjoyed the confidence and by the Speaker pro tempore, Mr. WASON. re pect of all persons who knew him. He was also regarded as Rev. William D. Waller, of Washington, D. C., offered the one of the substantial and influentfal citizens of his native State. following prayer : Outside of his profession he was acth-e in civic and political With reyerence ·we draw nigh to Thee, 0 God, to Thee in organi~ations. He served as a member of t.be House of Repre whom we live and moYe and haYe our being. sentati Yes of New Hampshire for the session of 1901-2; Bless us in our serYice this morning. :May we gat her in serYed as a member of the State board of charities and correc spiration from the liYes of those whom we remember to-day. tions from 1901to1917, inclusive; he served as a member of the We beseech Thee to sustain and bless their families and dear State board of equalization in 1910; and in every one of those ones. And as our friends go out into the unseen world, so positions he measured up to the requirements thereof and dis teach us to number our days that we may apply our hearts clrnrged the duties with ability and distinction. -

Saleable Compromises

MARKO ALA-FOSSI SALEABLE COMPROMISES Quality Cultures in Finnish and US Commercial Radio ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Tampere, for public discussion in the auditorium A1 of the University Main Building, Kalevantie 4, Tampere, on February 26th, 2005 at 12 o’clock. University of Tampere Tampere 2005 Marko Ala-Fossi SALEABLE COMPROMISES Quality Cultures in Finnish and US Commercial Radio Media Studies ACADEMIC DISSERTATION University of Tampere, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication FINLAND Copyright © Tampere University Press and Marko Ala-Fossi Sales Bookshop TAJU P.O. BOX 617 33014 University of Tampere Finland Tel. +358 3 215 6055 Fax +358 3 215 7685 email taju@uta.fi http://granum.uta.fi Cover: Mia Ristimäki Layout: Aila Helin Printed dissertation ISBN 951-44-6214-9 Electronic dissertation Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 414 ISBN 951-44-6213-0 ISSN 1456-954X http://acta.uta.fi Tampereen Yliopistopaino Oy – Juvenes Print Tampere 2005 “We all can buy the same records, play them on the same type of turntable and we can all hire someone to talk. The difference in radio is like the difference in soap – it depends on who puts on the best wrapper.” (Gordon McLendon in 1961, cited in Garay 1992, 70) The p.d., who had been with the station nine years, asked: “Do you think we can maintain our reputation for quality programming and still pull in a much larger audience?” The general manager leaned back in his armchair, thumped his sales reports, and said, “My defi nition of quality radio is whatever the No.