My Place in Art Teaching Kit 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Identity Portrait Unit

Cultural Identity Portrait Unit Drawing and Painting Level 4*, Year 9 This resource is offered as an example of a unit that engages with the “front end” of The New Zealand Curriculum (2007) – considering Vision, Principles, Values, and Key Competencies, as well as Achievement Objectives. *Teachers are encouraged to use or modify this work in any way they find helpful for their programmes and their students. For example, it may be inappropriate to assess all students at level 4. UNIT: Cultural Identity Portrait CURRICULUM LEVEL: 4 MEDIA: Drawing and Painting YEAR LEVEL: 9 DURATION: Approximately 16 – 18 Periods ASSESSMENT: Tchr & Peer DESCRIPTION OF UNIT Students research and paint a self-portrait that demonstrates an understanding of the Rita Angus work ‘Rutu’. CURRICULUM LINKS VISION: Confident – producing portraits of themselves that acknowledge elements of their cultural identity will help students to become confident in their own identity. Connected – working in pairs and small groups enables students to develop their ability to relate well to others. Producing a portrait which incorporates a range of symbols develops students’ abilities as effective users of communication tools. Lifelong learners – comparing traditional and contemporary approaches to painting portraits helps students to develop critical and creative thinking skills. PRINCIPLES: High Expectations – there are near endless opportunities for students to strive for personal excellence through the production of a self-portrait: students are challenged to make art works that clearly represent themselves both visually and culturally. Cultural diversity – students are introduced to portraits showing a range of cultures. They are required to bring aspects of their own cultural identity to the making of the portrait, and share these with other members of their class. -

Ascent03opt.Pdf

1.1.. :1... l...\0..!ll1¢. TJJILI. VOL 1 NO 3 THE CAXTON PRESS APRIL 1909 ONE DOLLAR FIFTY CENTS Ascent A JOURNAL OF THE ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND The Caxton Press CHRISTCHURCH NEW ZEALAND EDITED BY LEO BENSEM.AN.N AND BARBARA BROOKE 3 w-r‘ 1 Published and printed by the Caxton Press 113 Victoria Street Christchurch New Zealand : April 1969 Ascent. G O N T E N TS PAUL BEADLE: SCULPTOR Gil Docking LOVE PLUS ZEROINO LIMIT Mark Young 15 AFTER THE GALLERY Mark Young 21- THE GROUP SHOW, 1968 THE PERFORMING ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND: AN EXPLOSIVE KIND OF FASHION Mervyn Cull GOVERNMENT AND THE ARTS: THE NEXT TEN YEARS AND BEYOND Fred Turnovsky 34 MUSIC AND THE FUTURE P. Plat: 42 OLIVIA SPENCER BOWER 47 JOHN PANTING 56 MULTIPLE PRINTS RITA ANGUS 61 REVIEWS THE AUCKLAND SCENE Gordon H. Brown THE WELLINGTON SCENE Robyn Ormerod THE CHRISTCHURCH SCENE Peter Young G. T. Mofi'itt THE DUNEDIN SCENE M. G. Hire-hinge NEW ZEALAND ART Charles Breech AUGUSTUS EARLE IN NEW ZEALAND Don and Judith Binney REESE-“£32 REPRODUCTIONS Paul Beadle, 5-14: Ralph Hotere, 15-21: Ian Hutson, 22, 29: W. A. Sutton, 23: G. T. Mofiifi. 23, 29: John Coley, 24: Patrick Hanly, 25, 60: R. Gopas, 26: Richard Killeen, 26: Tom Taylor, 27: Ria Bancroft, 27: Quentin MacFarlane, 28: Olivia Spencer Bower, 29, 46-55: John Panting, 56: Robert Ellis, 57: Don Binney, 58: Gordon Walters, 59: Rita Angus, 61-63: Leo Narby, 65: Graham Brett, 66: John Ritchie, 68: David Armitage. 69: Michael Smither, 70: Robert Ellis, 71: Colin MoCahon, 72: Bronwyn Taylor, 77.: Derek Mitchell, 78: Rodney Newton-Broad, ‘78: Colin Loose, ‘79: Juliet Peter, 81: Ann Verdoourt, 81: James Greig, 82: Martin Beck, 82. -

My Place in Art Teaching Kit

My Place in Art Teaching Kit Summer in Nelson, 1960 Irvine Major, Oil on Canvas Unit Developed and Compiled by Esther McNaughton, Suter Educator Education services and programmes at The Suter are supported by the Ministry of Education under the Learning Experiences Outside of the Classroom (LEOTC) funding. 1 Introduction: My Place in Art In this lesson students will explore landscape art which shows our region. They will think about their associations with local places before looking at why and how artists show landscapes in art. The students will develop an artwork showing themselves in a landscape of their choice using techniques observed in the artworks on show. Relevant Curriculum Areas: Visual Arts, Social Studies, English. Duration: 75- 90 minutes depending on level. Levels: Adaptable for Years 1-10 Associated Suter Exhibition: Milk and Honey The rhetoric used to describe Aotearoa/New Zealand from a colonial perspective has always been laced with Biblical references. This is God’s own country: a South Pacific Eden full of hope, bounty and peace. This exhibition examines mythmaking involved in forging the history and vision of our country and Nelson as a region. Tracing the aesthetic influence of the top of the South Island, Milk and Honey displays the historical impact the region has had as a subject for art. From John Bevan Ford’s adaptation of one of the first European images of Maori and Aotearoa in Golden Bay and Tall Men on Hill Tops to Joe Sheehan’s contemporary approach to traditional Māori pakohe (argillite), this region has been stimulating artists for centuries. -

Bulletin Autumn Christchurch Art Gallery March — May B.156 Te Puna O Waiwhetu 2009

Bulletin Autumn Christchurch Art Gallery March — May B.156 Te Puna o Waiwhetu 2009 1 BULLETIN EDITOR Bulletin B.156 Autumn DAVID SIMPSON Christchurch Art Gallery March — May Te Puna o Waiwhetu 2009 GALLERY CONTRIBUTORS DIRECTOR: JENNY HARPER CURATORIAL TEAM: KEN HALL, JENNIFER HAY, FELICITY MILBURN, JUSTIN PATON, PETER VANGIONI PUBLIC PROGRAMMES: SARAH AMAZINNIA, LANA COLES PHOTOGRAPHERS: BRENDAN LEE, DAVID WATKINS OTHER CONTRIBUTORS ROBBIE DEANS, MARTIN EDMOND, GARTH GOULD, CHARLES JENCKS, BRIDIE LONIE, RICHARD MCGOWAN, ZINA SWANSON, DAVID TURNER TEL: (+64 3) 941 7300 FAX: (+64 3) 941 7301 EMAIL: [email protected], [email protected] PLEASE SEE THE BACK COVER FOR MORE DETAILS. WE WELCOME YOUR FEEDBACK AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE ARTICLES. CURRENT SUPPORTERS OF THE GALLERY AALTO COLOUR CHARTWELL TRUST CHRISTCHURCH ART GALLERY TRUST COFFEY PROJECTS CREATIVE NEW ZEALAND ERNST & YOUNG FRIENDS OF CHRISTCHURCH ART GALLERY GABRIELLE TASMAN HOLMES GROUP HOME NEW ZEALAND LUNEYS PHILIP CARTER PYNE GOULD CORPORATION SPECTRUM PRINT STRATEGY DESIGN & ADVERTISING THE PRESS THE WARREN TRUST UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY FOUNDATION VBASE WARREN AND MAHONEY Visitors to the Gallery in front of Fiona Hall’s The Price is Right, installed as part of the exhibition Fiona Hall: Force Field. DESIGN AND PRODUCTION ART DIRECTOR: GUY PASK Front cover image: Rita Angus EDITORIAL DESIGN: ALEC BATHGATE, A Goddess of Mercy (detail) 1945–7. Oil on canvas. Collection CLAYTON DIXON of Christchurch Art Gallery Te PRODUCTION MANAGER: -

Exhibitions & Events at Auckland Art Gallery Toi O

Below: Michael Illingworth, Man and woman fi gures with still life and fl owers, 1971, oil on canvas, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki MARITIME MUSEUM FERRY TERMINAL QUAY ST BRITOMART On Show STATION EXHIBITIONS & EVENTS CUSTOMS ST BEACH RD AT AUCKLAND ART GALLERY TOI O TĀMAKI FEBRUARY / MARCH / APRIL 2008 // FREE // www.aucklandartgallery.govt.nz ANZAC AVE SHORTLAND ST HOBSON ST HOBSON ALBERT ST ALBERT QUEEN ST HIGH ST PRINCES ST PRINCES BOWEN AVE VICTORIA ST WEST ST KITCHENER LORNE ST LORNE ALBERT PARK NEW MAIN WELLESLEY ST WEST STANLEY ST GALLERY GALLERY GRAFTON RD WELLESLEY ST AUCKLAND AOTEA R MUSEUM D SQUARE L A R O Y A M Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki Discount parking - $4 all day, weekends and PO Box 5449, Auckland 1141 public holidays, Victoria St carpark, cnr Kitchener New Gallery: Cnr Wellesley and Lorne Sts and Victoria Sts. After parking, collect a discount voucher from the gallery Open daily 10am to 5pm except Christmas Day and Easter Friday. Free guided tours 2pm daily For bus, train and ferry info phone MAXX Free entry. Admission charges apply for on (09) 366 6400 or go to www.maxx.co.nz special exhibitions The Link bus makes a central city loop Ph 09 307 7700 Infoline 09 379 1349 www.stagecoach.co.nz/thelink www.aucklandartgallery.govt.nz ARTG-0009-serial Auckland Art Gallery’s main gallery will be closing for development on Friday 29 February. Exhibitions and events will continue at the New Gallery across the road, cnr Wellesley & Lorne sts. On Show Edited by Isabel Haarhaus Designed by Inhouse ISSN 1177-4614 Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki relies on From the Chris Saines, the good will and generosity of corporate Gallery Floor Plans partners. -

About People

All about people RYMAN HEALTHCARE ANNUAL REPORT 2019 We see it as a privilege to look after older people. RYMAN HEALTHCARE 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 04 Chair’s report 12 Chief executive’s report 18 Our directors 20 Our senior executives 23 How we create value over time 35 Enhancing the resident experience 47 Our people are our greatest resource 55 Serving our communities 65 The long-term opportunities are significant 75 We are in a strong financial position 123 We value strong corporate governance 3 RYMAN HEALTHCARE CHAIR’S REPORT We continue to create value 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 RYMAN HEALTHCARE CHAIR Dr David Kerr Ryman has been a care company since it started 35 years ago. As we continue to grow, we continue to create value for our residents and their families, our staff, and our shareholders by putting care at the heart of everything we do. We’re a company with a purpose – to look after older people. We know that if we get our care and resident experience right, and have happy staff, the financial results take care of themselves. I believe purpose and profitability are comfortable companions. Integrating the two supports us in creating value over time. This year, we continue to use the Integrated Reporting <IR> Framework* to share the wider story of how we create that value. *For more information on the <IR> Framework, visit integratedreporting.org 5 RYMAN HEALTHCARE “I believe purpose As a company we’re very focused on growth, but we will not compromise our core value of and profitability are putting our residents first. -

Mccahon House Invites You to Dinner

McCahon House invites you to dinner McCahon House hosts three Artists in Residence per year. As part of each residency a bespoke dinner between our current artist and a guest chef is created. Join us for an evening of art inspired cuisine, and be part of an ongoing dialogue where ideas around art are exchanged amongst artists and peers. These events are exclusive to the Gate Project. We Roasted carrot with kaffir lime sauce invite you to join and help strengthen opportunities and orange blossom candy floss by for New Zealand’s artists and our culture. For more chef Alex Davies of Gatherings, information about the Gate Project and to join visit: Christchurch, in collaboration with mccahonhouse.org.nz/gate 2019 artist in resident, Jess Johnson. — The Gate Project ART + OBJECT Tel +64 9 354 4646 Free 0 800 80 60 01 3 Abbey Street Fax +64 9 354 4645 Newton Auckland [email protected] www.artandobject.co.nz PO Box 68345 Wellesley Street instagram: @artandobject Auckland 1141 facebook: Art+Object youtube: ArtandObject Photography: Sam Hartnett Design: Fount–via Print: Graeme Brazier Th is auction event, including art works made solely by Colin Marti Friedlander Gretchen Albrecht underneath McCahon's "As there is a McCahon, felt like a fi tting tribute in 2019, his Centenary constant fl ow of light ..." year. We hoped to put together a small off ering that would Courtesy the Gerrard and Marti Friedlander Charitable Trust refl ect the quality and variety of work that McCahon Marti Friedlander Archive, E.H. McCormick Research produced during his life-time and I think you will fi nd that Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, on loan from the Gerrard and Marti Friedlander Charitable Trust, 2002 within these pages. -

2016 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 INTRODUCTION Andre Brönnimann with two of the subjects of his winning portrait - Ria Wihapi Waikerepuru and Te Rawanake Robinson-Coles at the opening of the Adam Portraiture Award 2016. Treasurers, first John Sladden and then Richard 2016 was a year of Tuckey, to improve the quality of our budgets and endeavour, rewarded financial control. We are all very grateful for the commitment, the good humour and fellowship that over almost all of the full David brought to our affairs. Our fellow Trustee, Mike Curtis – a Partner with Deloitte – continued as range of our activities. It Chairman of the Finance and Planning Committee. presented us with a number In December we were pleased to be able to elect two new Trustees. Dr. David Galler, a well-known of challenges, ones of intensive care specialist in Auckland, and the personnel; of gallery space; author of a recent bestselling book about his life and work, Things That Matter. David brings his of governance; and, as wide knowledge of Auckland to our deliberations, along with a strong management background and always, of funding. a life-long interest in art. Helen Kedgley, who was Director of the Pātaka Art and Museum in Porirua But I would like to start by stating my own personal pleasure and satisfaction at the excellence of last year’s exhibition programme, a view that is shared, I know, by many of you. Quite apart from their intrinsic interest, and the pleasure as well as insight that they bring, these presentations are enhancing our reputation nationally and leading to increased cooperation with galleries and collectors both in this country and overseas. -

![COLIN Mccahon [1919-1987 Aotearoa New Zealand] ANNE Mccahon (Née HAMBLETT) [1915-1993 Aotearoa New Zealand]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4998/colin-mccahon-1919-1987-aotearoa-new-zealand-anne-mccahon-n%C3%A9e-hamblett-1915-1993-aotearoa-new-zealand-1794998.webp)

COLIN Mccahon [1919-1987 Aotearoa New Zealand] ANNE Mccahon (Née HAMBLETT) [1915-1993 Aotearoa New Zealand]

COLIN McCAHON [1919-1987 Aotearoa New Zealand] ANNE McCAHON (née HAMBLETT) [1915-1993 Aotearoa New Zealand] [Paintings for Children] 1944 Ink, pen, watercolour on paper Private Collection [Harbour Scene - Paintings for Children] 1944 Ink, pen, watercolour on paper Collection of the Forrester Gallery. Gifted by the John C. Parsloe Trust. [Ships and Planes – Paintings for Children] 1944 Ink, pen, watercolour on paper Private Collection, Wellington Colin McCahon met fellow artist Anne Hamblett in 1937 while both studying at the Dunedin School of Art. The couple married on 21 September 1942 and went on to have four children. In the mid-1940s, Anne began a sixteen-year long career as an illustrator, often illustrating children’s books, such as At the Beach by Aileen Findlay, published in 1943. During this time, the McCahons collaborated on the series known as Paintings for Children. This would be the first and only time the couple would produce work together. The subject-matter was divided among the two, Colin was responsible for the landscape, while Anne filled each scene with bustling activity, including buildings, trains, ships, cars and people. These works were exhibited at Dunedin’s Modern Books, a co-operative book shop, in November 1945. This exhibition received positive praise from an Art New Zealand reviewer, who said: “These pictures are the purest fun: red trains rushing into and out from tunnels, through round green hills, and over viaducts against clear blue skies; bright ships queuing up for passage through amazing canals or diligently unloading at detailed wharves, people and horses and aeroplanes overhead all very serious and busy… They will be lucky children indeed who get these pictures – too lucky perhaps because the pictures should be turned into picture books and then every good child might have the lot.” 1 Two years later, in 1947, a group of Colin McCahon’s new paintings were also exhibited at Modern Books. -

Five New Zealand Watercolou Rists

FIVE NEW ZEALAND WATERCOLOU RISTS NOV-DEC, 1958 I N T R O D U C T I O N i i:x i! 11:1 i II>N ttA8 r.r.i \ M;I; \.\H.U) in ivprfsent tisK vvlii.v [niniip.il iiK'dimn • is \vatcrcol(.tur. !ou>' lias been used to ,1 onisidi i.iiik- r.vti-m in :\rv, /_-. i ! i ir.u'ilnu ft -n ihc early i , at • . h .uui IIL-LLIUSI' :: tli ••. ! be , inec and ii i-in iis ;iji|tlii.-,iiii n than in li attists in this exhitilioin — frorh (.'hristchurch, VVeU ' : 'ul and ' ' i ' ill v -'I u n and ;i !c\\ h;!\f hcxn i_'\hilii:inu |',M n;.:ii\ \LVIIS. ! in.' c\i.iNl«. n >'.iii in nu -,', I . icd u'trnsjK-ttivf Hi' cxluiustivc in selection as .ill tin- artisU iiasv hccn Jihc. 1>. A. TO MO it I' .xoTi:: All ;': fjl .. '' I '.,,,, : . '' Oft, lire in inches, height before i> Lvqiiiries concerning purcnalei should m to the artist concerned through the Auckli: THE CATALOGUE RITA ANGUS 1 \VAIKANAE 184 x 14 Signed and dated Rita Angus '51. 2 MANGOMII Mix 15| Signed and dated Rita Angus '55. 3 KA1KOURA LANDSCAPE i5Jx22J Signed and dated Rita Angus '56 4 WESTSHORE, NAPIER £»x.22| Signed and dated Rita Angus '5/ 5 IRISES 22Sxl5j{ Signed and dated Rita Angus '58 *• 6 FUNGI 10{-xl4i Signed Rita Angus 7 MOUNT CAMEL 8} x 10i Signed Rita Angus 8 SUMMER 1 ! .x 14 Signed Rita Angus OLIVIA SPENCER BOWER 9 I LOWERS 18x23 Signed O/ii-ii< Spencer Boiver 10 CAMPING PLACE 12}xl5A Signed O/IIKJ Spencer Bower 11 TOKLESSE RANGE' BixK,l Signed Oliriti Spencer Bower 12 MOUNT PLENTY Hixl61 Sixncd Olivia Spencer Bower 13 NEAR QUELNSTOWN 13 x 17£ Signed Olivia Spencer Bou'cr 14 WET DAY, QUEENSTOWN -

NCEA Level 2 Art History (90228) 2011 Assessment Schedule

NCEA Level 2 Art History (90228) 2011 — page 1 of 4 Assessment Schedule – 2011 Art History: Examine subjects and themes in art (90228) Evidence Statement Question One: Māori Art / Taonga Achievement Achievement with Merit Achievement with Excellence For EACH of the two works: As for Achievement, plus: As for Merit, plus: Describes ONE key aspect of the Explains how the subject matter is Evaluates the significance of the subject matter. used to convey these themes / themes / ideas in Māori art. AND ideas. Explains the themes or ideas presented in EACH painting. Responses could include: Responses could include: Responses could include: Arnold Manaaki Wilson, Ode to Arnold Wilson uses his sculpture to Care of the natural resources of Tane Mahuta refer to traditional Māori use of New Zealand has been a big Subject timber for carving the sculptures that concern for many people in this reflected the identity of each tribe. country, particularly for Māori. From The subject of Arnold Wilson’s Carved pou, panels on the wharenui the first arrival of Europeans the installation is clearly spelled out – and on waka were the primary face of the country has altered his concern is with the timber images of Māori sculptors, and his greatly and many Māori felt cut off industry. He writes, “Where have all pou updates this tradition. He from their traditional land and the trees gone, overseas every one” contrasts this with a pile of bark resources. As the country became on a box on top of a pile of bark chips, which is a reference to the industrialised this process has chips. -

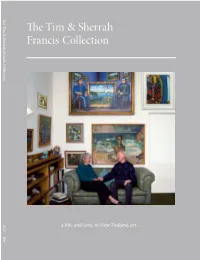

The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection

The Tim & Sherrah FrancisTimSherrah & Collection The The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection A+O 106 a life, and love, in New Zealand art… The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection Art + Object 7–8 September 2016 Tim and Sherrah Francis, Washington D.C., 1990. Contents 4 Our Friends, Tim and Sherrah Jim Barr & Mary Barr 10 The Tim and Sherrah Francis Collection: A Love Story… Ben Plumbly 14 Public Programme 15 Auction Venue, Viewing and Sale details Evening One 34 Yvonne Todd: Ben Plumbly 38 Michael Illingworth: Ben Plumbly 44 Shane Cotton: Kriselle Baker 47 Tim Francis on Shane Cotton 53 Gordon Walters: Michael Dunn 64 Tim Francis on Rita Angus 67 Rita Angus: Vicki Robson 72 Colin McCahon: Michael Dunn 75 Colin McCahon: Laurence Simmons 79 Tim Francis on The Canoe Tainui 80 Colin McCahon, The Canoe Tainui: Peter Simpson 98 Bill Hammond: Peter James Smith 105 Toss Woollaston: Peter Simpson 108 Richard Killeen: Laurence Simmons 113 Milan Mrkusich: Laurence Simmons 121 Sherrah Francis on The Naïve Collection 124 Charles Tole: Gregory O’Brien 135 Tim Francis on Toss Woollaston Evening Two 140 Art 162 Sherrah Francis on The Ceramics Collection 163 New Zealand Pottery 168 International Ceramics 170 Asian Ceramics 174 Books 188 Conditions of Sale 189 Absentee Bid Form 190 Artist Index All quotes, essays and photographs are from the Francis family archive. This includes interviews and notes generously prepared by Jim Barr and Mary Barr. Our Friends, Jim Barr and Mary Barr Tim and Sherrah Tim and Sherrah in their Wellington home with Kate Newby’s Loads of Difficult.