'Gens Anglorum' & 'Normanitas': the Bayeux Tapestry and the Effects Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and Earl of Kent

( 55 ) ODO, BISHOP OF BAYEUX AND EARL OF KENT. BY SER REGINALD TOWER, K.C.M.G., C.Y.O. IN the volumes of Archceologia Cantiana there occur numerous references to Bishop Odo, half-brother of William the Conqueror ; and his name finds frequent mention in Hasted's History of Kent, chiefly in connection with the lands he possessed. Further, throughout the records of the early Norman chroniclers, the Bishop of Bayeux is constantly cited among the outstanding figures in the reigns of William the Conqueror and of his successor William Rufus, as well as in the Duchy of Normandy. It seems therefore strange that there should be (as I am given to understand) no Life of the Bishop beyond the article in the Dictionary of National Biography. In the following notes I have attempted to collate available data from contemporary writers, aided by later historians of the period during, and subsequent to, the Norman Conquest. Odo of Bayeux was the son of Herluin of Conteville and Herleva (Arlette), daughter of Eulbert the tanner of Falaise. Herleva had .previously given birth to William the Conqueror by Duke Robert of Normandy. Odo's younger brother was Robert, Earl of Morton (Mortain). Odo was born about 1036, and brought up at the Court of Normandy. In early youth, about 1049, when he was attending the Council of Rheims, his half-brother, William, bestowed on him the Bishopric of Bayeux. He was present, in 1066, at the Conference summoned at Lillebonne, by Duke William after receipt of the news of Harold's succession to the throne of England. -

Machine Embroidery Threads

Machine Embroidery Threads 17.110 Page 1 With all the threads available for machine embroidery, how do you know which one to choose? Consider the thread's size and fiber content as well as color, and for variety and fun, investigate specialty threads from metallic to glow-in-the-dark. Thread Sizes Rayon Rayon was developed as an alternative to Most natural silk. Rayon threads have the soft machine sheen of silk and are available in an embroidery incredible range of colors, usually in size 40 and sewing or 30. Because rayon is made from cellulose, threads are it accepts dyes readily for color brilliance; numbered unfortunately, it is also subject to fading from size with exposure to light or frequent 100 to 12, laundering. Choose rayon for projects with a where elegant appearance is the aim and larger number indicating a smaller thread gentle care is appropriate. Rayon thread is size. Sewing threads used for garment also a good choice for machine construction are usually size 50, while embroidered quilting motifs. embroidery designs are almost always digitized for size 40 thread. This means that Polyester the stitches in most embroidery designs are Polyester fibers are strong and durable. spaced so size 40 thread fills the design Their color range is similar to rayon threads, adequately without gaps or overlapping and they are easily substituted for rayon. threads. Colorfastness and durability make polyester When test-stitching reveals a design with an excellent choice for children's garments stitches so tightly packed it feels stiff, or other items that will be worn hard stitching with a finer size 50 or 60 thread is and/or washed often. -

Bayeux Tapestry Writing Assignment You Do Not Have to Be A

Bayeux Tapestry Writing Assignment You do not have to be a needlepoint enthusiast to appreciate the magnificent Bayeux Tapestry, which chronicles the events leading up to the conquest of England by Duke William of Normandy in the year 1066. Technically speaking it is not a tapestry at all – but an embroidery, stitched with wool on a linen background by a team of needle workers. But the interesting question is: was it made just to celebrate a great victory? To answer this question you have to consider the political situation at the time. Duke William claimed that the King, Edward the Confessor, had promised him the throne of England. However this event had not been properly witnessed or recorded. He also claimed that Harold, the future King of England, had previously sworn allegiance to him. But Harold had been imprisoned in France at that time, and his actions could have been misunderstood. On Edward’s death, William of Normandy had expected to ascend the English throne. But instead Harold disputed his claims, insisting that the Kingdom had been bequeathed to him by the dying monarch, and was duly crowned King. William replied to this by invading England, defeating the English army and killing King Harold at the Battle of Hastings. Now the new King William had to ensure that history told the story his way. What better way to achieve this than with a huge 230 feet long tapestry – a priceless work of art, which would be preserved for centuries, and confirm his right, and that of his successors, to the throne of England. -

Press Kit 2020 the Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy

Press kit 2020 The Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy The Battle of Normandy History explained through objects Liberty Alley , a site for remembrance in Bayeux Visits to the museum News and calendar of events Key figures www.bayeuxmuseum.com Press contact : Fanny Garbe, Media Relations Officer Tel. +33 (0)2.31.51.20.49 - [email protected] 2 The Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy Situated near the British Military Cemetery of Bayeux, the Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy narrates the battles which took place in Normandy after the D-Day landings, between 7 th June and 29 th August 1944. The museum offers an exhibition surface of 2000m², entirely refurbished in 2006. The collections of military equipment, the diorama and the archival films allow the visitor to grasp the enormous effort made during this decisive battle in order to restore peace in Europe. A presentation of the overall situation in Europe before D- Day precedes the rooms devoted to the operations of the month of June 1944: the visit of General De Gaulle in Bayeux on 14 th June, the role of the Resistance, the Mulberry Harbours and the capture of Cherbourg. Visitors can then step into an exhibition hall based on the work of war reporters – a theme favoured by the City of Bayeux which organises each year the Prix Bayeux-Calvados for War Correspondents. Visitors will also find information on the lives of civilians living amongst the fighting in the summer of 1944 and details of the towns destroyed by the bombings. -

Anglo- Saxon England and the Norman Conquest, 1060-1066

1.1 Anglo- Saxon society Key topic 1: Anglo- Saxon England and 1.2 The last years of Edward the Confessor and the succession crisis the Norman Conquest, 1060-1066 1.3 The rival claimants for the throne 1.4 The Norman invasion The first key topic is focused on the final years of Anglo-Saxon England, covering its political, social and economic make-up, as well as the dramatic events of 1066. While the popular view is often of a barbarous Dark-Ages kingdom, students should recognise that in reality Anglo-Saxon England was prosperous and well governed. They should understand that society was characterised by a hierarchical system of government and they should appreciate the influence of the Church. They should also be aware that while Edward the Confessor was pious and respected, real power in the 1060s lay with the Godwin family and in particular Earl Harold of Wessex. Students should understand events leading up to the death of Edward the Confessor in 1066: Harold Godwinson’s succession as Earl of Wessex on his father’s death in 1053 inheriting the richest earldom in England; his embassy to Normandy and the claims of disputed Norman sources that he pledged allegiance to Duke William; his exiling of his brother Tostig, removing a rival to the throne. Harold’s powerful rival claimants – William of Normandy, Harald Hardrada and Edgar – and their motives should also be covered. Students should understand the range of causes of Harold’s eventual defeat, including the superior generalship of his opponent, Duke William of Normandy, the respective quality of the two armies and Harold’s own mistakes. -

Thread Yarn and Sew Much More

Thread Yarn and Sew Much More By Marsha Kirsch Supplies: • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Yarn embellishment foot set 920403096 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® 7 hole cord foot with threader 412989945 • HUSQVARNA VIKING ® Clear open toe foot 413031945 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Clear ¼” piecing foot 412927447 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Embroidery Collection # 270 Vintage Postcard • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Sensor Q foot 413192045 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® DESIGNER™ Royal Hoop 360X200 412944501 • INSPIRA® Cut away stabilize 141000802 • INSPIRA® Twin needles 2.0 620104696 • INSPIRA® Watercolor bobbins 413198445 • INSPIRA® 90 needle 620099496 © 2014 KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. VIKING, INSPIRA, DESIGNER and DESIGNER DIAMOND ROYALE are trademarks of KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. HUSQVARNA is a trademark of Husqvarna AB. All trademarks used under license by VSM Group AB • Warm and Natural batting • Yarn –color to match • YLI pearl crown cotton (color to match yarn ) • 2 spools of matching Robison Anton 40 wt Rayon thread • Construction thread and bobbin • ½ yard back ground fabric • ½ yard dark fabric for large squares • ¼ yard medium colored fabric for small squares • Basic sewing supplies and 24” ruler and making pen Cut: From background fabric: 14” wide by 21 ½” long From dark fabric: (20) 4 ½’ squares From medium fabric: (40) 2 ½” squares 21” W x 29” L (for backing) From Batting 21” W x 29” L From YLI Pearl Crown Cotton: Cut 2 strands 1 ¾ yds (total 3 ½ yds needed) From yarn: Cut one piece 5 yards © 2014 KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. VIKING, INSPIRA, DESIGNER and DESIGNER DIAMOND ROYALE are trademarks of KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. HUSQVARNA is a trademark of Husqvarna AB. All trademarks used under license by VSM Group AB Directions: 1. -

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021 SAMPLE OF PROGRAM* Day 1: Friday, May 21, 2021 Arrival in Paris on your own Group Welcome Dinner in a restaurant Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 2: Saturday May 22, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris. Guided visit of the church of St Pierre de Montmartre, one of the oldest extant churches in Paris, and the Sacré Coeur Basilica with its mosaic of Christ in Glory. Lunch on your own in historic Montmartre After lunch, meet your tour bus for a guided visit of the St Denis Basilica to learn about the birth of Gothic architecture Return to the hotel at the end of the day. Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 3: Sunday, May 23, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and your 2 guides in front of your hotel for a day trip to Chartres. Guided tour of Notre Dame de Chartres Cathedral, a unique example of early gothic architecture, th and its 13 century Labyrinth Group Lunch in a restaurant Free time to explore the town of Chartres Return to Paris with your tour bus at the end of the day Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 4: Monday, May 24, 2021 Meet your 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris (transport pass provided) Guided visit of Notre Dame Cathedral (the exterior), an iconic masterpiece of Gothic architecture, ravaged by fire in April 2019. -

The Norman Conquest: Ten Centuries of Interpretation (1975)

CARTER, JOHN MARSHALL. The Norman Conquest: Ten Centuries of Interpretation (1975). Directed by: Prof. John H. Beeler. The purpose of this study was to investigate the historical accounts of the Norman Conquest and its results. A select group of historians and works, primarily English, were investigated, beginning with the chronicles of medieval writers and continuing chronologically to the works of twentieth century historians. The majority of the texts that were examined pertained to the major problems of the Norman Conquest: the introduction of English feudalism, whether or not the Norman Conquest was an aristocratic revolution, and, how it affected the English church. However, other important areas such as the Conquest's effects on literature, language, economics, and architecture were observed through the "eyes" of past and present historians. A seconday purpose was to assemble for the student of English medieval history, and particularly the Norman Conquest, a variety of primary and secondary sources. Each new generation writes its own histories, seeking to add to the existing cache of material or to reinterpret the existing material in the light of the present. The future study of history will be significantly advanced by historiographic surveys of all major historical events. Professor Wallace K. Ferguson produced an indispensable work for students of the Italian Renaissance, tracing the development of historical thought from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. V Professor Bryce Lyon performed a similar task,if not on as epic a scale, with his essay on the diversity of thought in regard to the history of the origins of the Middle Ages. -

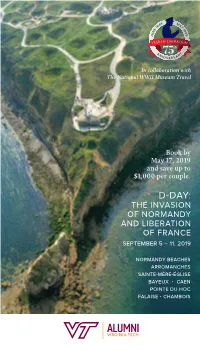

2019 Flagship Vatech Sept5.Indd

In collaboration with The National WWII Museum Travel Book by May 17, 2019 and save up to $1,000 per couple. D-DAY: THE INVASION OF NORMANDY AND LIBERATION OF FRANCE SEPTEMBER 5 – 11, 2019 NORMANDY BEACHES ARROMANCHES SAINTE-MÈRE-ÉGLISE BAYEUX • CAEN POINTE DU HOC FALAISE • CHAMBOIS NORMANDY CHANGES YOU FOREVER Dear Alumni and Friends, Nothing can match learning about the Normandy landings as you visit the ery places where these events unfolded and hear the stories of those who fought there. The story of D-Day and the Allied invasion of Normandy have been at the heart of The National WWII Museum’s mission since they opened their doors as The National D-Day Museum on June 6, 2000, the 56th Anniversary of D-Day. Since then, the Museum in New Orleans has expanded to cover the entire American experience in World War II. The foundation of this institution started with the telling of the American experience on D-Day, and the Normandy travel program is still held in special regard – and is considered to be the very best battlefield tour on the market. Drawing on the historical expertise and extensive archival collection, the Museum’s D-Day tour takes visitors back to June 6, 1944, through a memorable journey from Pegasus Bridge and Sainte-Mère-Église to Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc. Along the way, you’ll learn the timeless stories of those who sacrificed everything to pull-off the largest amphibious attack in history, and ultimately secured the freedom we enjoy today. Led by local battlefield guides who are experts in the field, this Normandy travel program offers an exclusive experience that incorporates pieces from the Museum’s oral history and artifact collections into presentations that truly bring history to life. -

On Our Doorstep Parts 1 and 2

ON 0UR DOORSTEP I MEMORIAM THE SECOD WORLD WAR 1939 to 1945 HOW THOSE LIVIG I SOME OF THE PARISHES SOUTH OF COLCHESTER, WERE AFFECTED BY WORLD WAR 2 Compiled by E. J. Sparrow Page 1 of 156 ON 0UR DOORSTEP FOREWORD This is a sequel to the book “IF YOU SHED A TEAR” which dealt exclusively with the casualties in World War 1 from a dozen coastal villages on the orth Essex coast between the Colne and Blackwater. The villages involved are~: Abberton, Langenhoe, Fingringhoe, Rowhedge, Peldon: Little and Great Wigborough: Salcott: Tollesbury: Tolleshunt D’Arcy: Tolleshunt Knights and Tolleshunt Major This likewise is a community effort by the families, friends and neighbours of the Fallen so that they may be remembered. In this volume we cover men from the same villages in World War 2, who took up the challenge of this new threat .World War 2 was much closer to home. The German airfields were only 60 miles away and the villages were on the direct flight path to London. As a result our losses include a number of men, who did not serve in uniform but were at sea with the fishing fleet, or the Merchant avy. These men were lost with the vessels operating in what was known as “Bomb Alley” which also took a toll on the Royal avy’s patrol craft, who shepherded convoys up the east coast with its threats from: - mines, dive bombers, e- boats and destroyers. The book is broken into 4 sections dealing with: - The war at sea: the land warfare: the war in the air & on the Home Front THEY WILL OLY DIE IF THEY ARE FORGOTTE. -

The Anglo-Saxon Period of English Law

THE ANGLO-SAXON PERIOD OF ENGLISH LAW We find the proper starting point for the history of English law in what are known as Anglo-Saxon times. Not only does there seem to be no proof, or evidence of the existence of any Celtic element in any appreciable measure in our law, but also, notwithstanding the fact that the Roman occupation of Britain had lasted some four hundred years when it terminated in A. D. 410, the last word of scholarship does not bring to light any trace of the law of Imperial Rome, as distinct from the precepts and traditions of the Roman Church, in the earliest Anglo- Saxon documents. That the written dooms of our kings are the purest specimen of pure Germanic law, has been the verdict of one scholar after another. Professor Maitland tells us that: "The Anglo-Saxon laws that have come down to us (and we have no reason to fear the loss of much beyond some dooms of the Mercian Offa) are best studied as members of a large Teutonic family. Those that proceed from the Kent and Wessex of the seventh century are closely related to the Continental folk-laws. Their next of kin seem to be the Lex Saxonum and the laws of the Lom- bards."1 Whatever is Roman in them is ecclesiastical, the system which in course of time was organized as the Canon law. Nor are there in England any traces of any Romani who are being suffered to live under their own law by their Teutonic rulers. -

Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of Terms Used in the Documentation – Blue Files and Collection Notebooks

Book Appendix Glossary 12-02 Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of terms used in the documentation – Blue files and collection notebooks. Rosemary Shepherd: 1983 to 2003 The following references were used in the documentation. For needle laces: Therese de Dillmont, The Complete Encyclopaedia of Needlework, Running Press reprint, Philadelphia, 1971 For bobbin laces: Bridget M Cook and Geraldine Stott, The Book of Bobbin Lace Stitches, A H & A W Reed, Sydney, 1980 The principal historical reference: Santina Levey, Lace a History, Victoria and Albert Museum and W H Maney, Leeds, 1983 In compiling the glossary reference was also made to Alexandra Stillwell’s Illustrated dictionary of lacemaking, Cassell, London 1996 General lace and lacemaking terms A border, flounce or edging is a length of lace with one shaped edge (headside) and one straight edge (footside). The headside shaping may be as insignificant as a straight or undulating line of picots, or as pronounced as deep ‘van Dyke’ scallops. ‘Border’ is used for laces to 100mm and ‘flounce’ for laces wider than 100 mm and these are the terms used in the documentation of the Powerhouse collection. The term ‘lace edging’ is often used elsewhere instead of border, for very narrow laces. An insertion is usually a length of lace with two straight edges (footsides) which are stitched directly onto the mounting fabric, the fabric then being cut away behind the lace. Ocasionally lace insertions are shaped (for example, square or triangular motifs for use on household linen) in which case they are entirely enclosed by a footside. See also ‘panel’ and ‘engrelure’ A lace panel is usually has finished edges, enclosing a specially designed motif.