Botswana's Important Bird Areas: Status and Trends Report 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malawi Trip Report 12Th to 28Th September 2014

Malawi Trip Report 12th to 28th September 2014 Bohm’s Bee-eater by Keith Valentine Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader: Keith Valentine RBT Malawi Trip Report September 2014 2 Top 10 Birds: 1. Scarlet-tufted Sunbird 2. Pel’s Fishing Owl 3. Lesser Seedcracker 4. Thyolo Alethe 5. White-winged Apalis 6. Racket-tailed Roller 7. Blue Swallow 8. Bohm’s Flycatcher 9. Babbling Starling 10. Bohm’s Bee-eater/Yellow-throated Apalis Top 5 Mammals: 1. African Civet 2. Four-toed Elephant Shrew 3. Sable Antelope 4. Bush Pig 5. Side-striped Jackal/Greater Galago/Roan Antelope/Blotched Genet Trip Summary This was our first ever fully comprehensive tour to Malawi and was quite simply a fantastic experience in all respects. For starters, many of the accommodations are of excellent quality and are also situated in prime birding locations with a large number of the area’s major birding targets found in close proximity. The food is generally very good and the stores and lodges are for the most part stocked with decent beer and a fair selection of South African wine. However, it is the habitat diversity that is largely what makes Malawi so good from a birding point of view. Even though it is a small country, this good variety of habitat, and infrastructure that allows access to these key zones, insures that the list of specials is long and attractive. Our tour was extremely successful in locating the vast majority of the region’s most wanted birds and highlights included Red-winged Francolin, White-backed Night Heron, African Cuckoo-Hawk, Western Banded Snake -

15-Day Zimbabwe Birding and Wildlife Spectacular

15-DAY ZIMBABWE BIRDING AND WILDLIFE SPECTACULAR With optional pre-tour to Mana Pools: special Birds, African mammals, and breathtaking scenery including Victoria Falls 1 – 15 FEBRUARY 2021 Racket-tailed Roller will be searched for throughout Zimbabwe. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | ITINERARY Zimbabwe 15 (18) days Zimbabwe is an absolutely fabulous country – scenically wonderful, with very friendly people fluent in English and, surprisingly to many people, with a truly excellent infrastructure. The hundreds of miles of paved roads are in very good condition, and it is one of the few African countries of which you can see a great deal without the use of a 4x4. With an improving political leadership and the change to the US Dollar as the local currency, which has greatly improved the economy, the country is once again fast becoming a very popular destination to birders, and right now it is still possible to get very comfortable accommodation at comparatively low rates. During our 18-day tour (which includes the 3-day pre-tour) you’ll see all the major habitats, sights, and birds of this wonderful country and end up with a very good bird list and loads of Africa’s big and small mammals. We begin with your international flight arriving in Harare, from where we take a charter flight to one of Africa’s wildest game parks, Mana Pools National Park. While this is one of the few game parks in Africa you can legally explore on foot, we do not advise this because of the presence of a host of dangerous animals. -

Zambia and Zimbabwe 28 �Ovember – 6 December 2009

Zambia and Zimbabwe 28 ovember – 6 December 2009 Guide: Josh Engel A Tropical Birding Custom Tour All photos taken by the guide on this tour. The Smoke that Thunders: looking down one end of the mile-long Victoria Falls. ITRODUCTIO We began this tour by seeing one of Africa’s most beautiful and sought after birds: African Pitta . After that, the rest was just details. But not really, considering we tacked on 260 more birds and loads of great mammals. We saw Zambia’s only endemic bird, Chaplin’s Barbet , as well as a number of miombo and broad-leaf specialties, including Miombo Rock-Thrush, Racket-tailed Roller, Southern Hyliota, Miombo Pied Barbet, Miombo Glossy Starling, Bradfield’s Hornbill, Pennant-winged ightjar, and Three-banded Courser. With the onset of the rainy season just before the tour, the entire area was beautifully green and was inundated with migrants, so we were able to rack up a great list of cuckoos and other migrants, including incredible looks at a male Kurrichane Buttonquail . Yet the Zambezi had not begun to rise, so Rock Pratincole still populated the river’s rocks, African Skimmer its sandbars, and Lesser Jacana and Allen’s Gallinule its grassy margins. Mammals are always a highlight of any Africa tour: this trip’s undoubted star was a leopard , while a very cooperative serval was also superb. Victoria Falls was incredible, as usual. We had no problems in Zimbabwe whatsoever, and our lodge there on the shores of the Zambezi River was absolutely stunning. The weather was perfect throughout the tour, with clouds often keeping the temperature down and occasional rains keeping bird activity high. -

Namibia & the Okavango

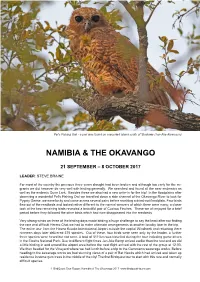

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

Private Governance of Protected Areas in Africa: Case Studies, Lessons Learnt and Conditions of Success

Program on African Protected Areas & Conservation (PAPACO) PAPACO study 19 Private governance of protected areas in Africa: case studies, lessons learnt and conditions of success @B. Chataigner Sue Stolton and Nigel Dudley Equilibrium Research & IIED Equilibrium Research offers practical solutions to conservation challenges, from concept, to implementation, to evaluation of impact. With partners ranging from local communities to UN agencies across the world, we explore and develop approaches to natural resource management that balance the needs of nature and people. We see biodiversity conservation as an ethical necessity, which can also support human wellbeing. We run our own portfolio of projects and offer personalised consultancy. Prepared for: IIED under contract to IUCN EARO Reproduction: This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission, provided acknowledgement to the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose without permission in writing from Equilibrium Research. Citation: Stolton, S and N Dudley (2015). Private governance of protected areas in Africa: Cases studies, lessons learnt and conditions of success. Bristol, UK, Equilibrium Research and London, UK, IIED Cover: Private conservancies in Namibia and Kenya © Equilibrium Research Contact: Equilibrium Research, 47 The Quays Cumberland Road, Spike Island Bristol, BS1 6UQ, UK Telephone: +44 [0]117-925-5393 www.equilibriumconsultants.com Page | 2 Contents 1. Executive summary -

2017 Namibia, Botswana & Victoria Falls Species List

Eagle-Eye Tours Namibia, Okavango and Victoria Falls November 2017 Bird List Status: NT = Near-threatened, VU = Vulnerable, EN = Endangered, CR = Critically Endangered Common Name Scientific Name Trip STRUTHIONIFORMES Ostriches Struthionidae Common Ostrich Struthio camelus 1 ANSERIFORMES Ducks, Geese and Swans Anatidae White-faced Whistling Duck Dendrocygna viduata 1 Spur-winged Goose Plectropterus gambensis 1 Knob-billed Duck Sarkidiornis melanotos 1 Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiaca 1 African Pygmy Goose Nettapus auritus 1 Hottentot Teal Spatula hottentota 1 Cape Teal Anas capensis 1 Red-billed Teal Anas erythrorhyncha 1 GALLIFORMES Guineafowl Numididae Helmeted Guineafowl Numida meleagris 1 Pheasants and allies Phasianidae Crested Francolin Dendroperdix sephaena 1 Hartlaub's Spurfowl Pternistis hartlaubi H Red-billed Spurfowl Pternistis adspersus 1 Red-necked Spurfowl Pternistis afer 1 Swainson's Spurfowl Pternistis swainsonii 1 Natal Spurfowl Pternistis natalensis 1 PODICIPEDIFORMES Grebes Podicipedidae Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis 1 Black-necked Grebe Podiceps nigricollis 1 PHOENICOPTERIFORMES Flamingos Phoenicopteridae Greater Flamingo Phoenicopterus roseus 1 Lesser Flamingo - NT Phoeniconaias minor 1 CICONIIFORMES Storks Ciconiidae Yellow-billed Stork Mycteria ibis 1 Eagle-Eye Tours African Openbill Anastomus lamelligerus 1 Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus 1 Marabou Stork Leptoptilos crumenifer 1 PELECANIFORMES Ibises, Spoonbills Threskiornithidae African Sacred Ibis Threskiornis aethiopicus 1 Hadada Ibis Bostrychia -

South-Central African and Miombo Woodland Endemics List of Birds

South-central African and Miombo woodland endemics List of birds most easily seen in southern Africa but NOT South Africa (primarily Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia, etc.) Primarily in Miombo Woodland unless other habitat stated in "Notes" column "Good places to see it" column - Many of these birds also occur in DRC, Angola and Zimbabwe Page Common Name # Good places to see it Notes Zambia Malawi Lilian's Lovebird 216 Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe Mopane woodland 1 1 Black-cheeked Lovebird 216 Zambian endemic Mopane woodland 1 Racket-tailed Roller 278 Malawi, Zambia, Mozambique 1 1 Pale-billed Hornbill 294 Malawi, Zambia, Mozambique 1 1 Anchieta's Barbet 298 Zambia 1 Whyte's Barbet 298 Malawi, Zambia, Mozambique 1 1 Chaplin's Barbet 302 Zambian endemic fig savannah 1 Miombo Pied Barbet 304 Malawi, Zambia 1 1 Pallid Honeyguide 312 Malawi, Zambia, Mozambique 1 1 Black-and-rufous Swallow 358 Zambia grassland 1 Angolan Cliff Swallow 362 Zambia rivers 1 Fülleborn's Longclaw 366 Zambia moist grassy areas 1 Rosy-throated Longclaw 368 Mozambique, Zambia, South Africa moist grassy areas 1 Grimwood's Longclaw 368 Zambia moist grassy areas 1 Woodland Pipit 372 Malawi, Zambia, Mozambique 1 1 Short-tailed Pipit 374 Zambia 1 Miombo Tit 392 Malawi, Zambia 1 1 non-miombo populations in West Spotted Creeper 396 Malawi, Zambia Africa 1 1 Boulder Chat 398 Botswana wooded rocky hillsides 1 Cabanis's Greenbul 414 Zambia forest 1 Grey-olive Greenbul 416 Malawi, Zambia forest 1 1 Black-collared Bulbul 426 Zambia forest 1 1 Miombo Rock Thrush 434 Malawi, Zambia 1 1 Miombo -

Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report

MIOMBO ECOREGION VISION REPORT Jonathan Timberlake & Emmanuel Chidumayo December 2001 (published 2011) Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 20 WWF - SARPO MIOMBO ECOREGION VISION REPORT 2001 (revised August 2011) by Jonathan Timberlake & Emmanuel Chidumayo Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 20 Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P.O. Box FM730, Famona, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe PREFACE The Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report was commissioned in 2001 by the Southern Africa Regional Programme Office of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF SARPO). It represented the culmination of an ecoregion reconnaissance process led by Bruce Byers (see Byers 2001a, 2001b), followed by an ecoregion-scale mapping process of taxa and areas of interest or importance for various ecological and bio-physical parameters. The report was then used as a basis for more detailed discussions during a series of national workshops held across the region in the early part of 2002. The main purpose of the reconnaissance and visioning process was to initially outline the bio-physical extent and properties of the so-called Miombo Ecoregion (in practice, a collection of smaller previously described ecoregions), to identify the main areas of potential conservation interest and to identify appropriate activities and areas for conservation action. The outline and some features of the Miombo Ecoregion (later termed the Miombo– Mopane Ecoregion by Conservation International, or the Miombo–Mopane Woodlands and Grasslands) are often mentioned (e.g. Burgess et al. 2004). However, apart from two booklets (WWF SARPO 2001, 2003), few details or justifications are publically available, although a modified outline can be found in Frost, Timberlake & Chidumayo (2002). Over the years numerous requests have been made to use and refer to the original document and maps, which had only very restricted distribution. -

Namibia & Botswana II 2018

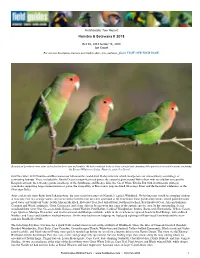

Field Guides Tour Report Namibia & Botswana II 2018 Oct 30, 2018 to Nov 18, 2018 Joe Grosel For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Rosy-faced Lovebirds were some of the first birds we saw in Namibia. We had wonderful looks at these colorful and charming little parrots at several locations, including the Erongo Wilderness Lodge. Photo by guide Joe Grosel. Our November 2018 Namibia and Botswana tour followed the established 18-day itinerary which incorporates an extraordinary assemblage of contrasting habitats. These included the Namib Desert's magnificent red dunes, the coastal region around Walvis Bay with its cold but very prolific Benguela current, the towering granite inselbergs of the Spitzkoppe and Erongo hills, the 'Great White' Etosha Pan with its numerous strategic waterholes supporting large concentrations of game, the tranquillity of Botswana's papyrus-lined Okavango River and the beautiful wilderness of the Okavango Delta. After a relatively short flight from Johannesburg, the tour started in earnest in Namibia's capital, Windhoek. No birding tour would be complete without at least one visit to a sewage works, and so we kicked off this tour on a first afternoon at the Gammams water purification works, which provided some good water and 'bushveld' birds. South African Shelduck, Hottentot Teal, Red-billed Duck, Southern Pochard, Red-knobbed Coot, African Gallinule, Common and Wood sandpipers, Great Cormorant, and a lone African Jacana were just some of the aquatic species seen. In the surrounding Acacia woodland there were Gray Go-away-birds, Rufous-vented Warbler, Pied Barbet, Cardinal Woodpecker, Brubru, Burnt-neck Eremomela, Yellow Canary, Cape Sparrow, Mariqua Flycatcher, and Scarlet-chested and Mariqua sunbirds, while in the reed beds we spotted Southern Red Bishop, African Reed Warbler, and Lesser and Southern masked-weavers. -

NESTLING MOUTH Marklngs It '" "' of OLD WORLD FINCHES ESTLLU MIMICRY and COEVOLUTION of NESTING

NESTLING MOUTH MARklNGS It '" "' OF OLD WORLD FINCHES ESTLLU MIMICRY AND COEVOLUTION OF NESTING r - .. ;.-; 5.i A&+.FINCHES .-. '4 AND THEIR VIDUA BROOD PARASITES - . , , . :.. - i ' -, ,' $*.$$>&.--: 7 -.: ',"L dt$=%>df;$..;,4;x.;b,?b;.:, ;.:. -, ! ,I Vt .., . k., . .,.-. , .is: 8, :. BY ERT B. PAYNE MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, NO. 194 Ann ntwi day, 2005 lSSN 0076-8405 PUBLICATIONS OF THE MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NO. 194 J. B. BLJR(.H,Editor JI.:NNIFERFBLMLEE, Assistcint Editor The publications of the Museum of Zoology, The University of Michigan, consist primarily of two series-the Mi.scel/aneous Pziblications and the Occa.siona1 Papers. Both series were founded by Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradshaw H. Swales, and Dr. W.W. Newcomb. Occasionally thc Museum publishes contributions outside of these series; beginning in 1990 thcsc arc titled Special Publications and arc numbered. All submitted manuscripts to any of the Museum's publications receive external review. The Occasional Papers, begun in 1913, serve as a medium for original studies based principally upon the collections in the Museum. They arc issued separately. When a sufficient number of pages has been printed to make a volume, a title page, table of contents, and an index are supplied to libraries and individuals on the mailing list for the series. The Miscellaneotls Pt~hlication.~,initiated in 1916, include monographic studies, papers on field and museum techniques, and other contributions not within the scope of the Occasional Papers, and are published separately. It is not intended that they be grouped into volurnes. Each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. -

ZIMBABWE CHECKLIST R=Rare, V=Vagrant, ?=Confirmation Required

ZIMBABWE CHECKLIST R=rare, V=vagrant, ?=confirmation required Common Ostrich Red-billed Teal Dark Chanting-goshawk Great Crested Grebe V Northern Pintail R Western Marsh-harrier Black-necked Grebe R Garganey African Marsh-harrier Little Grebe Northern Shoveler V Montagu's Harrier European Storm-petrel V Cape Shoveler Pallid Harrier Great White Pelican Southern Pochard African Harrier-hawk Pink-backed Pelican African Pygmy-goose Osprey White-breasted Cormorant Comb Duck Peregrine Falcon Reed Cormorant Spur-winged Goose Lanner Falcon African Darter Maccoa Duck Eurasian Hobby Greater Frigatebird V Secretarybird African Hobby Grey Heron Egyptian Vulture V Sooty Falcon R Black-headed Heron Hooded Vulture Taita Falcon Goliath Heron Cape Vulture Red-necked Falcon Purple Heron White-backed Vulture Red-footed Falcon Great Egret Rüppell's Vulture V Amur Falcon Little Egret Lappet-faced Vulture Rock Kestrel Yellow-billed Egret White-headed Vulture Greater Kestrel Black Heron Black Kite Lesser Kestrel Slaty Egret R Black-shouldered Kite Dickinson's Kestrel Cattle Egret African Cuckoo Hawk Coqui Francolin Squacco Heron Bat Hawk Crested Francolin Malagasy Pond-heron R European Honey-buzzard Shelley's Francolin Green-backed Heron Verreaux's Eagle Red-billed Spurfowl Rufous-bellied Heron Tawny Eagle Natal Spurfowl Black-crowned Night-heron Steppe Eagle Red-necked Spurfowl White-backed Night-heron Lesser Spotted Eagle Swainson's Spurfowl Little Bittern Wahlberg's Eagle Common Quail Dwarf Bittern Booted Eagle Harlequin Quail Eurasian Bittern V African -

Botswana-Namibia-2-Book 1.Indb

© Lonely Planet 413 Index amoebic dysentery 392 Bathoen 55 ABBREVIATIONS animals, see also Big Five, wildlife, bats 142 B Botswana individual animals Batswana people (B) 62 N Namibia Botswana 72 Battle of Moordkoppie (N) 251 Zam Zambia endangered species 74-5, 96, 227, Battle of Waterberg (N) 206 Zim Zimbabwe 297, 321 Bayei people (B) 63 Namibia 225, 321 beaches (N) 316 safety 50 Bechuanaland Democratic Party !nara melons 335 anteaters 74 (BDP) 57 /AE//Gams Arts Festival (N) 221, antelopes 115, 116, 193 Bechuanaland People’s Party (BPP) 239, 370 architecture 57 books 313 beer A Botswana 66-7 Botswana 71 aardvarks 74 Namibia 220-1, 350, 6 Namibia 223, 316 aardwolves 225 area codes, see inside front cover Bethanie (N) 345-6 abseiling 183 Arnhem Cave (N) 342-3 bicycle travel, see cycling accommodation, see also individual art galleries Big Five 50, 72, 97, 132 locations Botswana 151 Big Tree (Zim) 195 Botswana 158-9 National Art Gallery (N) 238 bilharzia (schistosomiasis) 391 Namibia 363-5 arts, see also individual arts Bird Island (N) 327 INDEX activities, see also individual activities Botswana 66-70 Bird Paradise (N) 328 Botswana 158-60 Namibia 218-22 birds 44-7 Namibia 365-6 ATMs Botswana 74 Victoria Falls 183-5 Contemporary San Art Gallery & Namibia 226 Africa fish eagles 45, 44 Craft Shop 165 bird-watching African wild dogs 116, 117, 132, Namibia 372 Botswana 103, 115, 132, 134, 136, 152 Attenborough, David 316 136 Agate Bay (N) 351 Aus (N) 347 Namibia 152, 267-8 Agricultural Museum (N) 346 Aus-Lüderitz Rd (N) 347-8 Zambia 183 Aha Hills