Download No More Bloody Bundles for Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 2 Wednesday 05 December 2012 10:30 Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers The Clive Pavilion Ludlow Racecourse Ludlow SY8 2BT Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers (Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 2) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1001 Rugby League tickets, postcards and handbooks Rugby 1922 S C R L Rugby League Medal C Grade Premiers awarded League Challenge Cup Final tickets 6th May 1950 and 28th to L McAuley of Berry FC. April 1956 (2 tickets), 3 postcards – WS Thornton (Hunslet), Estimate: £50.00 - £65.00 Hector Crowther and Frank Dawson and Hunslet RLFC, Hunslet Schools’ Rugby League Handbook 1963-64, Hunslet Schools’ Rugby Union 1938-39 and Leicester City v Sheffield United (FA Cup semi-final) at Elland Road 18th March 1961 (9) Lot: 1002 Estimate: £20.00 - £30.00 Keighley v Widnes Rugby League Challenge Cup Final programme 1937 played at Wembley on 8th May. Widnes won 18-5. Folded, creased and marked, staple rusted therefore centre pages loose. Lot: 1009 Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 A collection of Rugby League programmes 1947-1973 Great Britain v New Zealand 20th December 1947, Great Britain v Australia 21st November 1959, Great Britain v Australia 8th October 1960 (World Cup Series), Hull v St Helens 15th April Lot: 1003 1961 (Challenge Cup semi-final), Huddersfield v Wakefield Rugby League Championship Final programmes 1959-1988 Trinity 19th May 1962 (Championship final), Bradford Northern including 1959, 1960, 1968, 1969, 1973, 1975, 1978 and -

The Sydney Cricket Ground: Sport and the Australian Identity

The Sydney Cricket Ground: Sport and the Australian Identity Nathan Saad Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney This paper explores the interrelationship between sport and culture in Australia and seeks to determine the extent to which sport contributes to the overall Australian identity. It uses the Syndey Cricket Ground (SCG) as a case study to demonstrate the ways in which traditional and postmodern discourses influence one’s conception of Australian identity and the role of sport in fostering identity. Stoddart (1988) for instance emphasises the utility of sports such as cricket as a vehicle through which traditional British values were inculcated into Australian society. The popularity of cricket in Australia constitutes perhaps what Markovits and Hellerman (2001) coin a “hegemonic sports culture,” and thus represents an influential component of Australian culture. However, the postmodern discourse undermines the extent to which Australian identity is based on British heritage. Gelber (2010) purports that contemporary Australian society is far less influenced by British traditions as it was prior to WWII. The influence of immigration in Australia, and the global ascendency of Asia in recent years have led to a shift in national identity, which is reflected in sport. Edwards (2009) and McNeill (2008) provide evidence that traditional constructions of Australian sport minimise the cultural significance of indigenous athletes and customs in shaping national identity. Ultimately this paper argues that the role of sport in defining Australia’s identity is relative to the discourse employed in constructing it. Introduction The influence of sport in contemporary Australian life and culture seems to eclipse mere popularity. -

The Australian Women's Health Movement and Public Policy

Reaching for Health The Australian women’s health movement and public policy Reaching for Health The Australian women’s health movement and public policy Gwendolyn Gray Jamieson Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Gray Jamieson, Gwendolyn. Title: Reaching for health [electronic resource] : the Australian women’s health movement and public policy / Gwendolyn Gray Jamieson. ISBN: 9781921862687 (ebook) 9781921862670 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Birth control--Australia--History. Contraception--Australia--History. Sex discrimination against women--Australia--History. Women’s health services--Australia--History. Women--Health and hygiene--Australia--History. Women--Social conditions--History. Dewey Number: 362.1982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents Preface . .vii Acknowledgments . ix Abbreviations . xi Introduction . 1 1 . Concepts, Concerns, Critiques . 23 2 . With Only Their Bare Hands . 57 3 . Infrastructure Expansion: 1980s onwards . 89 4 . Group Proliferation and Formal Networks . 127 5 . Working Together for Health . 155 6 . Women’s Reproductive Rights: Confronting power . 179 7 . Policy Responses: States and Territories . 215 8 . Commonwealth Policy Responses . 245 9 . Explaining Australia’s Policy Responses . 279 10 . A Glass Half Full… . 305 Appendix 1: Time line of key events, 1960–2011 . -

RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1

rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 RFL Official Guide 201 2 rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 2 The text of this publication is printed on 100gsm Cyclus 100% recycled paper rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 CONTENTS Contents RFL B COMPETITIONS Index ........................................................... 02 B1 General Competition Rules .................. 154 RFL Directors & Presidents ........................... 10 B2 Match Day Rules ................................ 163 RFL Offices .................................................. 10 B3 League Competition Rules .................. 166 RFL Executive Management Team ................. 11 B4 Challenge Cup Competition Rules ........ 173 RFL Council Members .................................. 12 B5 Championship Cup Competition Rules .. 182 Directors of Super League (Europe) Ltd, B6 International/Representative Community Board & RFL Charities ................ 13 Matches ............................................. 183 Past Life Vice Presidents .............................. 15 B7 Reserve & Academy Rules .................. 186 Past Chairmen of the Council ........................ 15 Past Presidents of the RFL ............................ 16 C PERSONNEL Life Members, Roll of Honour, The Mike Gregory C1 Players .............................................. 194 Spirit of Rugby League Award, Operational Rules C2 Club Officials ..................................... -

Leigh Rugby Club Was Formed in 1878 and Has Been the Heartbeat of the Community Ever Since

Leigh Rugby Club was formed in 1878 and has been the heartbeat of the community ever since. One of the few towns in England where Rugby League is the dominant sport, Leigh’s own history is intrinsically linked with the fortunes of its rugby league club. Indeed, our town’s crest features a Latin motto which means ‘Progress with Unity’ something we always strive to instil. If you visit Leigh on a Sunday morning you will witness hundreds of children playing the game of rugby league. At our community clubs like Leigh Miners Rangers and Leigh East you will find entire families committed encouraging the disciplines and togetherness of our sport. It is a story reflected in Leigh’s own history where generations of the same family have pulled on the hooped shirt with pride. Both Leigh East and Leigh Miners play a kick away from Leigh Sports Village, a facility which has regenerated the town since it opened more than 10 years ago. More than just a stadium, this is a complex which has welcomed Champions League winners Bayern Munich and Rugby League World Champions Australia for training. Next year, the stadium will host several matches in the Rugby League World Cup and will also be a host venue for the Women’s European Football Championships. Manchester United Women have played their games at the stadium since their formation and global TV coverage means the name of the Leigh Sports Village is now a familiar one with sports fans across the world. It is a stadium which ‘Leythers’ are happy to call home and the atmosphere on match days can take your breath away. -

Diasporic Belonging, Masculine Identity and Sports: How Rugby League Affects the Perceptions and Practices of Pasifika Peoples in Australia

Diasporic Belonging, Masculine Identity and Sports: How rugby league affects the perceptions and practices of Pasifika peoples in Australia A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Gina Louise Hawkes BA (Hons) University of Sydney School of Global Urban and Social Studies College of Design and Social Context RMIT University April 2019 i I certify that except where due acknowledgement has been made, the work is that of the author alone; the work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award; the content of the thesis is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program; any editorial work, paid or unpaid, carried out by a third party is acknowledged; and, ethics procedures and guidelines have been followed. I acknowledge the support I have received for my research through the provision of an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Gina Hawkes 11/04/19 ii Acknowledgements To RMIT University for accepting and funding me and to all the staff who helped along the way, thank you. To my family and friends who have endured me, encouraged me, questioned me, and lifted me up when I needed it most, you are the light in my life. I want to particularly give thanks to Ashleigh Wardell, Frances Morrice, Megan Donker, Lara Williams and Mark Ashmore for being my ride or dies. To Sophia Hanover, Rob Larsen, Sam Burkley and Anoushka Klaus, thank you for always welcoming me into your homes on my numerous visits to Melbourne. -

Vs Dewsbury Moor

NATIONAL CONFERENCE LEAGUE TWO 2018 SEASON OFFICIAL MATCH DAY PROGRAMME S T C A L N R NI SA NGLEY Vs Saddleworth Rangers Vs DewsburySaturday 24th March Moor 2018 Match Ball Sponsored by The Crown & Anchor Rodley ADMISSION & PROGRAMME £2.50 www.stanningleyrugby.co.uk www.stanningleyrugby.co.uk The Crown & Anchor pub promises that you will be assured of a warm welcome and a friendly service. We offer the finest selection of beers and real ales. A great venue for special events with a relaxing Beer Garden to the rear. Come and have a drink - we look forward to seeing you soon. Football, rugby and horse racing on 5 large TV screens Saturday DJ 80’s and 90’s, 8pm - 12am Livemost FridayBands nights! S T C A L N R N SA INGLEY S T C VIEW FROM A L N R N SA THE CHAIR INGLEY SATURDAY 24TH MARCH 2018 Welcome to the players, officials and supporters from Saddleworth for this afternoons NCL Division 2 game. Honours were even last time we played in 2016, Saddleworth winning at their place 42 – 22 and we got the points at home 16 – 10. The season has really had a shocking start weather wise for some clubs, this is only Saddleworths second game of the season and no doubt they will be hoping to get off the mark after a defeat at Askam two weeks ago. We have been more fortunate with no postponements but after our flier in the first game away at Leigh East we have come a bit unstuck with defeats at home to Dewsbury Moor and away last week at Wigan St Judes. -

Download the Trophy Cabinet

ACT Heritage Library Heritage ACT Captain of the Canberra Raiders Mal Meninga holding up the Winfield Cup to proud fans after the team won the club’s first premiership against Balmain, 1989. The Trophy CabINeT Guy Hansen Rugby league is a game that teaches you lessons. My big lesson Looking back to those days I realise that football was very much came in 1976 when the mighty Parramatta Eels were moving in part of the fabric of the Sydney in which I grew up. The possibility a seemingly unstoppable march towards premiership glory. As of grand final glory provided an opportunity for communities to a 12-year-old, the transformation of Parramatta from perennial take pride in the achievements of the local warriors who went cellar-dwellers was a formative event. I had paid my dues with into battle each weekend. Winning the premiership for the first fortnightly visits to Cumberland Oval and was confident that a time signalled the coming of age for a locality and caused scenes Parramatta premiership victory was just around the corner. In the of wild celebration. Parramatta’s victory over Newtown in 1981 week before the grand final I found myself sitting on a railway saw residents of Sydney’s western city spill onto the streets in bridge above Church Street, Parramatta, watching Ray Higgs, a spontaneous outpouring of joy. Children waved flags from the the legendary tackling machine and Parramatta captain, lead family car while Dad honked the horn. Some over-exuberant fans the first-grade team on a parade through the city. -

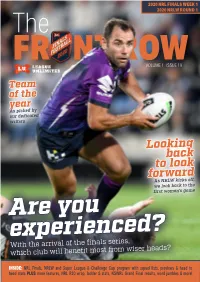

Looking Back to Look Forward

2020 NRL FINALS WEEK 1 The 2020 NRLW ROUND 1 FRONT ROW VOLUME 1 · ISSUE 19 Team of the year As picked by our dedicated writers Looking back to look forward As NRLW kicks off, we look back to the first women's game Are you experienced? With the arrival of the finals series, which club will benefit most from wiser heads? INSIDE: NRL Finals, NRLW and Super League & Challenge Cup program with squad lists, previews & head to head stats PLUS more features, NRL R20 wrap, ladder & stats, NSWRL Grand Final results, word jumbles & more! What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - ISSUE 19 Tim Costello From the editor 2 We made it! It's finals time in the NRL and there are plenty of intriguing storylines tailing into the business end of the Feature LU team of the year 3 season. Can the Roosters overcome a record loss to record Feature NRL Finals experience 4-5 a three-peat? Will Penrith set a new winning streak record to claim their third premiership? What about the evergreen Feature First women's game 6-7 Melbourne Storm - can they grab yet another title... and in Feature Salford's "private hell" 8 all likelihood top Cameron Smith's illustrious career? That and many more questions remain to be answered. Stay Feature Knights to remember 9 tuned. Word Jumbles, Birthdays 9 This week we have plenty to absorb in the pages that follow. THE WRAP · NRL Round 20 10-14 From analysis of the most Finals experience among the top eight sides, to our writers' team of the year, to a look back at Match reports 10-12 the first women's game in Australia some 99 years ago.. -

Sample Download

NO HELMETS REQUIRED Pitch PublishingPublishing LtdLtd A2 Yeomanoman GaGatete Yeomann WayWay Durringtongton BN13 3QZ3QZ Email: [email protected]@pitchpublishing.co.uk Web: www.pitchpublishing.co.ukwww.pitchpublishing.co.uk First publishedd by PitchPitch PublishingPublishing 20132013 Text © 2013 Gavin Willacy Gavin Willacy has asserted his rights in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identifi ed as the author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher and the copyright owners, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization.Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the terms stated here should be sent to the publishers at the UK address printed on this page. The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 13-digit ISBN: 9781909178472 Design and typesetting by Duncan Olner Managed and Manufactured by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY LMETS UIRED THE REMARKABLEB STORY OF AN ALL STARS GAVIN WILLACY INTRODUCTION I can clearly picture the moment this all started: I was on a platform at West Hampstead station in London, on my way to work as a sports journalist. I was reading Our Game magazine and became engrossed in a feature by Tony Collins about Mike Dimitro and his American All Stars. -

Clive Sullivan Story

THE CLIVE SULLIVAN STORY TRUE PROFESSIONAL JAMES ODDY Contents Foreword 8 Acknowledgements 9 A World Cup 11 A Proper Introduction 19 Setting the Scene 22 Clive Sullivan Arrives 34 The Airlie Bird Catches the Worm 40 Dicing With Death 53 Meeting Rosalyn 59 Beauty and Brutality 65 A Clear Run – Finally 74 Breakthrough and Breakdown 79 Married Life 85 Down and Out 94 Triumph, at Last 101 Upheaval 113 French Flair 122 World Cup and Coach Clive 130 The Second Division 140 Making the Switch 148 Family Man 163 Indian Summer 167 Close to the Promised Land 177 ‘Turn off the lights’ 187 Moving On 195 The Ecstasy 204 The Agony 210 Never Forgotten 217 Legacy 221 Bibliography 223 A World Cup HE Stade de Gerland in Lyon, France, was not the most obvious choice for the Rugby League World Cup Final Even in 1972, Twhen the French were much more of a force in the international game than in 2017, Lyon was a long way from the game’s heartlands in the south of the country When Great Britain and Australia emerged into the vast stadium, led by captains Clive Sullivan and Graeme Langlands respectively, they were met with nearly empty stands The official attendance was said to be 4,000, leaving large pockets of concrete stand exposed in a venue capable of holding over 40,000 Aside from the location, the French had also had a largely disappointing tournament, dampening what little interest might have remained Even the chill of this mid-November afternoon was unappealing, making the grey of the terraces appear even bleaker on BBC’s television coverage The crowd -

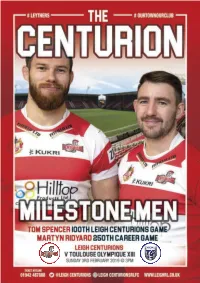

1Toulouse.Pdf

aaa Leigh v Toulouse 56pp.qxp_Layout 1 01/02/2019 08:49 Page 1 aaa Leigh v Toulouse 56pp.qxp_Layout 1 01/02/2019 08:39 Page 2 # LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB# OURTOWNOURCLUB aaa Leigh v Toulouse 56pp.qxp_Layout 1 01/02/2019 08:39 Page 3 # LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB# OURTOWNOURCLUB MIKEFROM LATHAM THE TOP CHAIRMAN,Welcome to Leigh Sports Village OPERATIONAL for that day would soon be our BOARD Messiah. Chris Hall came along and filmed the this afternoon’s Betfred On 1 November we had to file our new-look Leigh, working to put the Championship opener against preliminary 2019 squad list to the RFL. pride back into the club. His fantastic Toulouse Olympique. On it were just two names. By three-minute feature on ITV Granada It’s great to be back isn’t it? Last Christmas we had 20 and the reached out to 750k viewers. Sunday’s Warm Up game against metamorphosis was almost complete. The last few weeks have been hectic, London Broncos was a really The key to it all, appointing John Duffy preparing for the season and at the worthwhile exercise and it was great to as coach. He immediately injected Championship launch at York there was see over 2,000 Leigh fans in the positivity, local knowledge and a ready a palpable air of excitement for the ground, despite the bitterly cold smile, a bulging contacts book and with prospects of a great competition to weather. it a long list of players who were come. We are extremely grateful to our bursting to play for the club.