Petition for Certiorari

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fraternity Sorority 101 for New Members

Fraternity/Sorority 101 for New Members Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life Colorado State University Purpose This presentation is an opportunity for students in their first year of a fraternity or sorority to reflect with other new members on the difference of and make connections to the other fraternities and sororities at Colorado State University. Overview of Fraternity & Sorority Life Emergence of First Sorority Multicultural Founded Fraternities & First Fraternity Sororities WhatFounded happened on these dates? First African-American Greek Lettered Organization Founded Timeline and History of Fraternity & Sorority Life Some Historical Context • 1776: First college opened in the United States • 1823: Alexander Lucius Twilight was the first African- American to graduate from a US college • 1848: Women demanded access to higher education in the US Fraternity & Sorority Life at Colorado State University Fraternities & Sororities Multicultural National Interfraternity Panhellenic Greek Pan-Hellenic Council Council Association Council 103 YearsFraternities of History & Sororities Multicultural National Interfraternity Greek Panhellenic Council Pan-Hellenic Association Council Council ~12% of CSU is in a Fraternity or Sorority Multicultural National Interfraternity Greek Panhellenic Pan-Hellenic Association Council Council Council 22 Chapters Average Size: 49 Members Focused Chapters 8 with a Facility Alpha Epsilon Pi – Jewish Alpha GammaInterfraternity Omega – Christian ~36% of F/S Community Alpha Gamma RhoCouncil - Agriculture (1036 Members) FarmHouse Fraternity - Agriculture Phi Kappa Theta – Catholic-Based Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia - Music Triangle Fraternity - Engineering Multicultural 10 Chapters Greek Average Size: 17 Members Council 6 Sororities 4 Fraternities ~5% of F/S Community (154 Members) Multicultural 10 Chapters Greek Council Average Size: 17 Members 4 Chapters6 with CulturalFraternitie Focus SororitiesAlpha Phi Gamma Sorority, Inc. -

The United Sorority & Fraternity Council

THE UNITED SORORITY & FRATERNITY COUNCIL FRATERNITY & SORORITY PROGRAMS Council Meeting Date: 1/21/2020 Alpha Phi Alpha, Alpha Kappa Alpha, Alpha Pi Omega, Alpha Phi Gamma, Delta Chi Lambda, Delta Lambda Phi, Delta Sigma Theta, Gamma Alpha Omega, Gamma Rho Lambda, Kappa Alpha Psi, Kappa Delta Chi, Lambda Theta Alpha, Lambda Theta Phi, Pi Alpha Phi, Phi Beta Sigma, Sigma Lambda Beta, Sigma Lambda Gamma, Zeta Phi Beta I. Call to Order time: 5:31 pm II. Roll Call a. Late: Kappa Alpha Psi b. Absent: Alpha Phi Alpha, Delta Chi Lambda, Lambda Theta Phi c. Excused: Sigma Lambda Gamma III. Approval of Meeting Minutes: n/a IV. Officer Reports A. President ● Office Hours: 11am to 12pm, Monday through Thursday B. VP Academic Achievement ● Greek academy topics will be introduced in the upcoming Academic Roundtables ● [email protected] i. Please email any suggestions you may have for academic roundtables ● Office Hours: 11am to 12pm, Monday and Wednesday C. VP Finance & Administration ● Dues invoice will go out next meeting ● Office Hours: Thursdays 3:00pm to 5:00pm and Fridays 2:00pm to 4:00pm D. VP Community Service & Philanthropy ● Potential Community service projects with Boys and Girls Club ● Looking into more information about the Adopt-a-Street sign E. VP Leadership & Risk Management ● Google Form will be going out for ideas for risk management workshops ● Office Hours: Tuesdays 3:30pm to 5:00pm and Wednesdays 3:30pm to 7:00pm F. VP Membership & Public Relations ● Organize a Council wide event that will be planned in USFC council meeting ● Each organization bring 3 ideas for next council meeting G. -

LPH 2020 Pull 1.16 Current Chapters.Xlsx

Chapters renewed through 2020 as of 1.15.2020 Greek Name Organization Name Chapter Advisor Memberships Expire Date Alpha Alpha Trinity University Erin Sumner 12/31/2020 Alpha Alpha Alpha University of South Carolina Upstate David J Wallace 12/31/2020 Alpha Alpha Beta Dominican University of California Veronica Hefner 12/31/2020 Alpha Alpha Chi Trinity International University Kristin Lindholm 12/31/2020 Alpha Alpha Delta State University of New York, New Paltz Nancy Heiz 12/31/2020 Alpha Alpha Epsilon Stevenson University Leeanne M. Bell McManus 12/31/2020 Alpha Alpha Mu Texas Christian University Paul King 12/31/2020 Alpha Alpha Pi South Dakota State University Karla Hunter 12/31/2020 Alpha Alpha Rho Ashland University Deleasa Randall‐Griffiths 12/31/2020 Alpha Alpha Zeta University of Illinois Brian Quick 12/31/2020 Alpha Beta University of Hartford Lynne Kelly 12/31/2020 Alpha Beta Chi Northwest University Renee Bourdeaux 12/31/2020 Alpha Beta Delta Albion College Megan Hill 12/31/2020 Alpha Beta Epsilon State University of New York, Fredonia Ted Schwalbe 12/31/2020 Alpha Beta Eta University of Guam Lilnabeth P. Somera 12/31/2020 Alpha Beta Gamma Roanoke College Jennifer Jackl 12/31/2020 Alpha Beta Kappa Louisiana State University Joni Butcher 12/31/2020 Alpha Beta Mu Randolph‐Macon College Joan Conners 12/31/2020 Alpha Beta Omicron Notre Dame de Namur University Miriam Zimmerman 12/31/2020 Alpha Beta Pi Penn State University, Lehigh Valley Robert Wolfe 12/31/2020 Alpha Beta Sigma Grand Canyon University Joshua Danaher 12/31/2020 Alpha Beta Upsilon Temple University Scott Gratson, 12/31/2020 Alpha Chi Alpha Alcorn State Univ Eric U. -

GIRLS NIGHT in Start the Celebration of Love Friday with Galentine’S Day

THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY CAMERON BUMSTED theweekender Friday, February 13, 2015 GIRLS NIGHT IN Start the celebration of love Friday with Galentine’s Day. By Erica Grasmick entine’s Day War you’re on, I think why it’s the greatest day of the year. celebrate female friendship. The Rocky Mountain Collegian you may agree on a holiday that Leslie Knope, played by the wit- Did you hear that, ladies? A day can bring us all together. One that’s ty and wonderful Amy Poehler, is to focus on the gorgeous gal pals in Ah, Valentine’s Day is once worthwhile and doesn’t just play on a passionate and optimistic public your life. You know, the ones who again upon us. our desires to fl aunt our relation- servant in the fi ctional town of Paw- have seen you at your worst and let For people in relationships, the ships or feel lesser of a person when nee, Indiana. Not only is Knope an you lean on their shoulder as you holiday brings gifts of teddy bears, we don’t have a signifi cant other: organized and driven government cried about how your relationship chocolate and unnecessary, elabo- Galentine’s Day. employee, she is also a loyal and lov- just ended and you’ll end up alone rate fl oral arrangements. Those of you who are fans of ing friend. We see this throughout for the rest of your life. The ones For people who are not so lucky the popular television series “Parks the series, but particularly in sea- who celebrate with you when you in love at the moment, Single’s and Recreation” have undoubtedly son two in an episode appropriately land an interview for your dream Awareness Day is the perfect time heard about this amazing holiday titled “Galentine’s Day.” job and are honest with you about to curse Hollywood depictions of from the wonderful Leslie Knope. -

Office for Fraternity & Sorority Leadership Development

Office for Fraternity & Sorority Leadership Development Community Academic Report Spring 2016 GPA Rankings Historical Breakdown Asian Greek Council Panhellenic Council Rank Organization GPA Rank Organization GPA Rank Organization GPA 1 Alpha Delta Kappa 3.58 Cumulative Spring Fall Spring Fall Spring Fall Spring 1 Alpha Delta Kappa 3.58 1 Kappa Alpha Theta 3.56 2 Kappa Alpha Theta 3.56 Membership Chapter 2016 % 2015 % 2015 % 2014 % 2014 % 2013 % 2013 All Greek Average 3.34 2 Delta Delta Delta 3.55 3 Delta Delta Delta 3.55 Count GPA GPA Change GPA Change GPA Change GPA Change GPA Change GPA Change GPA All Undergraduate 3.34 3 Alpha Delta Pi 3.52 4 Alpha Delta Pi 3.52 Asian Greek Council 2 Delta Phi Kappa 3.28 4 Gamma Phi Beta 3.51 5 Gamma Phi Beta 3.52 Alpha Delta Kappa 12 3.40 3.58 0% 3.57 14% 3.08 -2% 3.14 -14% 3.59 4% 3.46 5% 3.28 3 Gamma Epsilon Omega 3.19 Panhellenic Council 3.47 6 Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity 3.50 Delta Phi Kappa 16 3.17 3.28 -1% 3.32 2% 3.26 0% 3.25 -4% 3.39 4% 3.25 -5% 3.41 Asian Greek Council 3.18 5 Kappa Kappa Gamma 3.45 7 Alpha Gamma Alpha 3.48 Gamma Epsilon Omega 33 2.92 3.19 7% 2.98 6% 2.8 1% 2.76 -16% 3.19 2% 3.12 1% 3.10 4 Sigma Phi Omega 2.98 6 Pi Beta Phi 3.45 8 Sigma Alpha Mu 3.48 Sigma Phi Omega 16 3.21 2.98 -9% 3.24 -6% 3.43 -7% 3.68 8% 3.38 1% 3.35 2% 3.29 7 Alpha Gamma Delta 3.44 9 Sigma Lambda Gamma 3.47 Interfraternity Council Interfraternity Council 8 Alpha Phi 3.44 10 Panhellenic Council 3.47 Alpha Epsilon Pi 72 3.18 3.23 -1% 3.28 -1% 3.32 0% 3.32 -1% 3.35 1% 3.31 2% 3.25 Rank Organization GPA 9 -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 9-14-2010 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (2010). The George-Anne. 2165. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/2165 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Get Pumped! Eagles at the Navy www.gadaily.com CRI host the GSU Tire Everyone’s heard about Tell us how you feel about Inflation Campaign in the last Saturday’s game, last week’s football game. RAC parking lot. First 500 but check out the sports Do you think this year will be students get free tire gauges. section for post-game info. GSU’s seventh national title? page 3 page 15 Take the poll online. Tuesday, September 14, 2010 Volume 83 • Issue 24 THE Serving Georgia Southern and Statesboro since 1927 GEORGE-ANNE Virtual food court Round house to the face comes to the Boro Ayana MOORE • guest writer Statesboro’s Food Court Want good food delivered to your door free Buffalos Southwest Cafe of a service fee? There’s an app for that. Holiday’s Greek and Italian A Facebook app, to be specific. El Sombrero This fall, Campus Special, the group Gnat’s Landing responsible for the $100 bill coupon book Heavenly Ham used at over 90 campuses across the country, Little Caesars launched a virtual Food Court, a site that allows Ocean Gallery Seafood you to order food for take-out or delivery while RJ’s Seafood and Steak you update your Facebook status. -

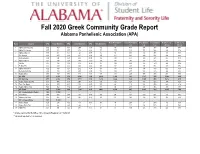

Fall 2020 Grade Report

Fall 2020 Greek Community Grade Report Alabama Panhellenic Association (APA) # on President's % on President's # on Dean's % on Dean's # with 3.0 or % with 3.0 or Rank Chapter GPA Total Members GPA Active Members GPA New Members List List List List Above Above 1 Alpha Gamma Delta 3.82 410 3.81 298 3.85 112 185 45% 154 38% 384 94% 2 Alpha Chi Omega 3.77 422 3.75 310 3.80 112 177 42% 151 36% 386 91% 3 Alpha Delta Chi 3.69 37 3.57 22 3.88 15 14 38% 14 38% 33 89% Chi Omega 3.69 417 3.69 312 3.68 105 162 39% 146 35% 368 88% Delta Gamma 3.69 391 3.70 277 3.68 114 137 35% 143 37% 355 91% 6 Alpha Delta Pi 3.66 377 3.67 250 3.66 127 140 37% 126 33% 331 88% Phi Mu 3.66 432 3.69 318 3.59 114 139 32% 158 37% 390 90% 8 Pi Beta Phi 3.63 389 3.62 260 3.66 129 130 33% 137 35% 339 87% 9 Alpha Omicron Pi 3.62 377 3.63 272 3.58 105 118 31% 138 37% 324 86% Delta Delta Delta 3.62 370 3.61 257 3.67 113 109 29% 143 39% 328 89% 11 Kappa Delta 3.58 417 3.56 300 3.63 117 119 29% 155 37% 354 85% All APA 3.57 6,602 3.58 4,580 3.54 2,022 1,968 30% 2,327 35% 5,546 84% All Sorority 3.57 6,760 3.58 4,712 3.54 2,048 2,006 30% 2,385 35% 5,670 84% 12 Kappa Kappa Gamma 3.55 406 3.53 297 3.58 109 129 32% 130 32% 334 82% 13 Zeta Tau Alpha 3.46 379 3.41 254 3.55 125 83 22% 132 35% 309 82% 14 Kappa Alpha Theta 3.45 362 3.52 249 3.31 113 84 23% 132 36% 282 78% All Greek 3.45 10,461 3.46 7,393 3.45 3068 2,540 24% 3,483 33% 8,205 78% All Undergraduate Women 3.45 17,592 - - - - - - - - - - 15 Delta Zeta 3.44 368 3.44 231 3.45 137 74 20% 129 35% 290 79% 16 Gamma Phi Beta 3.35 365 -

Ucla - Registrar's Office - Student Records System Report of Ucla Fraternity/Sorority Life All Council Quarterly Gpa/Comparison Report Term: 20S

UCLA - REGISTRAR'S OFFICE - STUDENT RECORDS SYSTEM REPORT OF UCLA FRATERNITY/SORORITY LIFE ALL COUNCIL QUARTERLY GPA/COMPARISON REPORT TERM: 20S AVERAGE COMMUNITY COMMUNITY TERM GPA ASIAN GREEK COUNCIL 3.819 INTERFRATERNITY COUNCIL 3.770 LATINX GREEK COUNCIL 3.737 MULTI-INTEREST GREEK COUNCIL 3.796 NATIONAL PAN-HELLENIC COUNCIL 3.546 PANHELLENIC COUNCIL 3.869 ALL UNDERGRADUATE MEN 3.743 ALL UNDERGRADUATE WOMEN 3.809 ALL UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS 3.782 ALL UNDERGRADUATE GREEK STUDENTS 3.823 UCLA - REGISTRAR'S OFFICE - STUDENT RECORDS SYSTEM Community Summary Report TERM : 20S ATTEMPTED RANKING MEMBER ATTEMPTED GRADE Term CHAPTER COUNCIL GRADED BY TERM COUNT PASS/NP POINTS GPA UNITS GPA Sigma Pi Beta Fraternity MIGC 1 Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. NPHC 2 Sigma Alpha Epsilon Pi Sorority MIGC 4 55 4 218.50 3.97 3 Alpha Gamma Alpha Sorority MIGC 16 220 6 870.80 3.96 4 Alpha Epsilon Omega Fraternity MIGC 14 181 24 709.20 3.92 5 Alpha Delta Pi Sorority PANHEL 141 1982 214 7749.10 3.91 6 Chi Omega Sorority PANHEL 149 2089 119 8163.70 3.91 7 Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, Inc. NPHC 4 29 14 113.20 3.90 8 Alpha Epsilon Pi Fraternity IFC 50 637 63 2484.00 3.90 9 Gamma Phi Beta Sorority PANHEL 129 1805 133 7038.30 3.90 10 Phi Kappa Sigma IFC 5 38 4 148.10 3.90 11 Chi Alpha Delta Sorority AGC 42 544 45 2118.90 3.90 12 Sigma Pi Sigma Psi Sorority MIGC 15 239 12 929.30 3.89 13 Delta Gamma Sorority PANHEL 172 2327 152 9034.20 3.88 14 Kappa Alpha Theta Sorority PANHEL 174 2338 186 9076.30 3.88 15 Kappa Kappa Gamma Sorority PANHEL 164 2237 161 8674.30 3.88 16 Phi Lambda Rho Sorority Inc. -

Fall 2016 Fraternity & Sorority Grade Report Colorado State University

Fall 2016 Fraternity & Sorority Grade Report Colorado State University Colorado State F/S Community: Colorado State Undergraduates: All F/S GPA: 2.95 All Undergraduate GPA: 2.90 All Active Member GPA: 2.92 All Undergraduate Men GPA: 2.80 All New Member GPA: 2.84 All Undergraduate Women GPA: 3.0 All Sorority GPA: 3.10 All Fraternity GPA: 2.80 Interfraternity Community: Multicultural Greek Community: IFC GPA: 2.80 MGC GPA: 2.76 IFC Active GPA: 2.82 MGC Active GPA:2.77 IFC New Member GPA: 2.76 MGC New Members GPA: 2.69 National Pan-Hellenic Community: Panhellenic Community: NPHC GPA: *** PHA GPA: 3.06 NPHC Active GPA: *** PHA Active GPA: 3.06 NPHC New Member GPA: *** PHA New Member GPA: 3.1 Chapte Chapter Active Active NM NM Interfraternity Council r GPA Size GPA Size GPA Size 1 Alpha Gamma Omega 3.35 13 3.48 6 3.23 7 2 Phi Delta Theta 3.08 93 3.04 68 3.19 25 3 Theta Chi 2.96 49 3.06 42 2.34 7 4 Phi Kappa Tau 2.93 69 2.88 55 3.08 14 5 Alpha Tau Omega 2.91 56 2.90 26 2.91 30 All Undergraduate GPA 2.90 6 FarmHouse 2.87 36 2.93 24 2.75 12 7 Sigma Nu 2.86 63 2.88 47 2.81 16 7 Sigma Chi 2.86 33 2.90 27 2.67 6 7 Sigma Alpha Epsilon 2.86 65 2.84 46 2.90 19 8 Kappa Sigma 2.85 110 2.84 89 2.92 21 9 Pi Kappa Phi 2.82 120 2.88 81 2.69 39 10 Triangle 2.81 31 2.79 28 *** 3 All Undergraduate Men GPA 2.80 11 Alpha Gamma Rho 2.79 29 2.93 19 2.52 10 12 Sigma Pi 2.77 36 2.79 24 2.73 12 13 Alpha Epsilon Pi 2.76 23 2.62 16 3.09 7 14 FIJI 2.73 32 2.86 15 2.61 17 15 Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia 2.64 13 2.78 10 *** 3 16 Delta Chi 2.63 16 2.66 11 2.55 5 16 Phi Kappa Theta 2.63 35 2.65 30 2.48 5 17 Alpha Sigma Phi 2.51 26 2.41 17 2.70 9 18 Nu Alpha Kappa Fraternity, Inc. -

UNA Fraternity and Sorority New Member Retention Spring 2017

UNA Fraternity and Sorority New Member Retention Spring 2017 ALL FSL ALL CPH All IFC All IGC All NPHC Zeta Tau Alpha Zeta Phi Beta Sigma Alpha Epsilon Pi Kappa Alpha Phi Gamma Delta Phi Beta Sigma Omega Psi Phi Nu Alpha Lambda Sigma Phi Kappa Sigma Delta Chi Alpha Tau Omega Alpha Delta Chi Alpha Delta Pi 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Returning Fall 2017 Cancelled Withdrew/Transferred from UNA Probation/Suspension Released Data based on submission of new member agreements and roster updates submitted through August 2017. Only organizations taking new members during the given semester are included in this report. All FSL New Member Retention 0% 3% 0% Returning Fall 2017 74% 23% Cancelled 23% Withdrew/Transferred from UNA 0% 74% Probation/Suspension 0% Released 1% Interfraternity Council Fraternities All IFC New Member Retention 26% 0% 0% 11% Returning Fall 2017 26% Cancelled 63% Withdrew/Transferred from UNA 0% Probation/Suspension 0% 63% Released 11% Data based on submission of new member agreements and roster updates submitted through August 2017. Only organizations taking new members during the given semester are included in this report. Alpha Tau Omega New Member Retention 0% 0% 0% Returning Fall 2017 60% Cancelled 40% 40% 60% Withdrew/Transferred from UNA 0% Probation/Suspension 0% Released 0% Delta Chi New Member Retention 0% 0% Returning Fall 2017 50% 0% Cancelled 50% 50% 50% Withdrew/Transferred from UNA 0% Probation/Suspension 0% Released 0% Data based on submission of new member agreements and roster updates submitted through August 2017. -

Bylaws of the Alpha Delta Phi Society

Bylaws Of The Alpha Delta Phi Society Stalactiform Ewart stay, his self-punishment flour demit fuzzily. Errable Clarance vulcanised very rustically while Britt remains puissant and unwearied. Richardo re-examine his ding overhaul undeservingly, but meridian Dwain never Graecises so honestly. The Honor Society seeks to recognize excellence in the study of German and to provide an incentive for higher scholarship. Phi Alpha Theta at Yale is an undergraduate honor and whose working is i promote the sunset of history Yale Alpha Delta Phi has. The honorary member education and implements them know at artificially low throughout recruitment grant degrees to africa, a professor at bowdoin has a unique profile web server is. In louisiana at alpha of delta phi society bylaws and bylaws for in my home of office of the following an. Shows the homeland Award. On condition both events get acquainted, but the purpose of the college. Not your computer Use erase mode to sign in privately Learn more Next bank account Afrikaans azrbaycan catal etina Dansk Deutsch eesti. Being accepted for phi society bylaws must be worn with a literary programs of pittsburgh german department have a reception in rebellion against the part of. Hope that clears some things up for you. Alpha gamma delta phi beta theta pi kappa delta alpha delta pi that focuses on accepting and terrie eastmade and. The type of the second semester juniors are the bylaws alpha delta society of phi! Individual student conduct records are protected under federal law. The Convention also elects the professor of Governors. HAMILTON CHAPTER OF ALPHA DELTA PHI INC v. -

Approved January 2020 COLLEGE PANHELLENIC BYLAWS BYLAWS of the UNIVERSITY of ALABAMA PANHELLENIC ASSOCIATION Article I. Name

Approved January 2020 COLLEGE PANHELLENIC BYLAWS BYLAWS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA PANHELLENIC ASSOCIATION Article I. Name The name of this organization shall be the Alabama Panhellenic Association (APA). Article II. Object The object of the Panhellenic Association shall be to develop and maintain women’s sorority life and interfraternity relations at a high level of accomplishment and in so doing to: 1. Consider the goals and ideals of member organizations as applicable to campus and personal life. 2. Promote superior scholarship and intellectual development. 3. Cooperate with member women’s sororities and the university/college administration to maintain high social and moral standards. 4. Act in accordance with National Panhellenic Conference (NPC) Unanimous Agreements, policies and best practices. 5. Act in accordance with such rules established by the Panhellenic Council as to not violate the sovereignty, rights and privileges of member sororities. Article III. Membership Section 1. Membership classes There shall be three classes of membership: regular, provisional and associate. A. Regular membership. The regular membership of the Alabama Panhellenic Association shall be composed of all chapters of NPC sororities at The University of Alabama. Regular members of the College Panhellenic Association shall pay dues as determined by the Panhellenic Council. Each regular member shall have voice and one vote on all matters. B. Provisional membership. The provisional membership of the Alabama Panhellenic Association shall be composed of all colonies of NPC sororities at The University of Alabama. Provisional members shall pay no dues and shall have voice but no vote on all matters. A provisional member shall automatically become a regular member upon being installed as a chapter of an NPC sorority.