The Just Intonation Automat – a Musically Adaptive Interface

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

WORKSHOP: Around the World in 30 Instruments Educator’S Guide [email protected]

WORKSHOP: Around The World In 30 Instruments Educator’s Guide www.4shillingsshort.com [email protected] AROUND THE WORLD IN 30 INSTRUMENTS A MULTI-CULTURAL EDUCATIONAL CONCERT for ALL AGES Four Shillings Short are the husband-wife duo of Aodh Og O’Tuama, from Cork, Ireland and Christy Martin, from San Diego, California. We have been touring in the United States and Ireland since 1997. We are multi-instrumentalists and vocalists who play a variety of musical styles on over 30 instruments from around the World. Around the World in 30 Instruments is a multi-cultural educational concert presenting Traditional music from Ireland, Scotland, England, Medieval & Renaissance Europe, the Americas and India on a variety of musical instruments including hammered & mountain dulcimer, mandolin, mandola, bouzouki, Medieval and Renaissance woodwinds, recorders, tinwhistles, banjo, North Indian Sitar, Medieval Psaltery, the Andean Charango, Irish Bodhran, African Doumbek, Spoons and vocals. Our program lasts 1 to 2 hours and is tailored to fit the audience and specific music educational curriculum where appropriate. We have performed for libraries, schools & museums all around the country and have presented in individual classrooms, full school assemblies, auditoriums and community rooms as well as smaller more intimate settings. During the program we introduce each instrument, talk about its history, introduce musical concepts and follow with a demonstration in the form of a song or an instrumental piece. Our main objective is to create an opportunity to expand people’s understanding of music through direct expe- rience of traditional folk and world music. ABOUT THE MUSICIANS: Aodh Og O’Tuama grew up in a family of poets, musicians and writers. -

The Applachian Mountain Dulcimer: Examining the Creation of an “American Tradition”

CFA MU 755, Boston University Steve Eulberg The Applachian Mountain Dulcimer: Examining the Creation of an “American Tradition” In a nation composed dominantly of immigrants, or people who are not “from” here, one can expect the cultural heritage in general, and the musical heritage in particular, to be based on the many strands of immigrant tradition. At some point, however, that which was brought from the old country begins to “belong” to the children of the immigrants, who pass this heritage on to their children. These strands are the woof that is woven into the warp of the new land—a process that continues until the tradition rightly belongs to the new setting as well. This is the case for the Applachian Mountain (or fretted, lap, plucked, strummed1) dulcimer. This instrument has been called by some “The Original American Folk Instrument.”2 Because other instruments have also laid claim to this appellation (most notably the banjo), this paper will explore whether or not it deserves such a name by describing the dulcimer, exploring its antecedent instruments, or “cousins”, tracing its construction and use by some people associated with the dulcimer, and examining samples of the music played on the instrument from 3 distinct periods of its use in the 20th century. What is the dulcimer? The Appalachian Mountain Dulcimer3 consists of a diatonic fretboard which is mounted on top of a soundbox. It is generally strung with three or four strings arranged in a pattern of three (with one pair of strings doubled and close together, to be played as one.) Its strings are strummed or plucked either with the fingers or a plectrum while the other hand is fretting the strings at different frets using either fingers or a wooden stick called a “noter.” The shape of the body or soundbox varies from hourglass, boat, diamond and lozenge, to teardrop and rectangular box style. -

The Mathematics of Musical Instruments

The Mathematics of Musical Instruments Rachel W. Hall and Kreˇsimir Josi´c August 29, 2000 Abstract This article highlights several applications of mathematics to the design of musical instru- ments. In particular, we consider the physical properties of a Norwegian folk instrument called the willow flute. The willow flute relies on harmonics, rather than finger holes, to produce a scale which is related to a major scale. The pitches correspond to fundamental solutions of the one-dimensional wave equation. This \natural" scale is the jumping-off point for a discussion of several systems of scale construction|just, Pythagorean, and equal temperament|which have connections to number theory and dynamical systems and are crucial in the design of keyboard instruments. The willow flute example also provides a nice introduction to the spectral theory of partial differential equations, which explains the differences between the sounds of wind or stringed instruments and drums. 1 Introduction The history of musical instruments goes back tens of thousands of years. Fragments of bone flutes and whistles have been found at Neanderthal sites. Recently, a 9; 000-year-old flute found in China was shown to be the world's oldest playable instrument.1 These early instruments show that humans have long been concerned with producing pitched sound|that is, sound containing predominantly a single frequency. Indeed, finger holes on the flutes indicate that these prehistoric musicians had some concept of a musical scale. The study of the mathematics of musical instruments dates back at least to the Pythagoreans, who discovered that certain combinations of pitches which they considered pleasing corresponded to simple ratios of frequencies such as 2:1 and 3:2. -

The Legacy of Virdung: Rare Books on Music from the Collection of Frederick R

THE LEGACY OF VIRDUNG: RARE BOOKS ON MUSIC FROM THE COLLECTION OF FREDERICK R. SELCH March 2006 – June 2006 INTRODUCTION FREDERICK R. SELCH (1930-2002) Collector, scholar, performer, advertising executive, Broadway musical producer, magazine publisher, and editor (Ovation); organizer of musical events, including seven exhibitions (two at the Grolier Club), president and artistic director of the Federal Music Society, music arranger, musical instrument repairer and builder; book binder; lecturer and teacher; and most of all, beloved raconteur who knew something about almost every subject. He earned a Ph.D. from NYU in American studies just before his death, writing a highly praised dissertation: “Instrumental Accompaniments for Yankee Hymn Tunes, 1760-1840.” In short, Eric (as he was known) did it all. Eric was a practitioner of material culture, studying the physical and intellectual evidence found in objects, images, the written word, oral history, sound, and culture. Consequently, his interpretations and conclusions about musical topics are especially immediate, substantive, and illuminating. He has left a great legacy for those of us interested in organology (the scientific study of musical instruments) and in particular, American music history. As a collector, Eric’s first serious instrument purchase (aside from those he regularly played) was a seventeenth-century European clavichord he acquired from an extraordinary dealer, Sydney Hamer, in Washington, D.C., where Eric was stationed during the Korean War. Hamer helped focus his eye and develop his taste. Following his service, he worked in London, then studied music and opera stage production and set design in Milan, and opera staging and voice in Siena. -

Romanian Traditional Musical Instruments

GRU-10-P-LP-57-DJ-TR ROMANIAN TRADITIONAL MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS Romania is a European country whose population consists mainly (approx. 90%) of ethnic Romanians, as well as a variety of minorities such as German, Hungarian and Roma (Gypsy) populations. This has resulted in a multicultural environment which includes active ethnic music scenes. Romania also has thriving scenes in the fields of pop music, hip hop, heavy metal and rock and roll. During the first decade of the 21st century some Europop groups, such as Morandi, Akcent, and Yarabi, achieved success abroad. Traditional Romanian folk music remains popular, and some folk musicians have come to national (and even international) fame. ROMANIAN TRADITIONAL MUSIC Folk music is the oldest form of Romanian musical creation, characterized by great vitality; it is the defining source of the cultured musical creation, both religious and lay. Conservation of Romanian folk music has been aided by a large and enduring audience, and by numerous performers who helped propagate and further develop the folk sound. (One of them, Gheorghe Zamfir, is famous throughout the world today, and helped popularize a traditional Romanian folk instrument, the panpipes.) The earliest music was played on various pipes with rhythmical accompaniment later added by a cobza. This style can be still found in Moldavian Carpathian regions of Vrancea and Bucovina and with the Hungarian Csango minority. The Greek historians have recorded that the Dacians played guitars, and priests perform songs with added guitars. The bagpipe was popular from medieval times, as it was in most European countries, but became rare in recent times before a 20th century revival. -

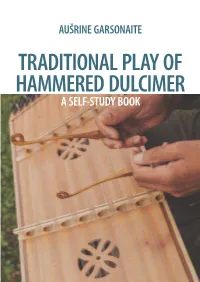

Traditional Play of Hammered Dulcimer a Self-Study Book Traditional Play of Hammered Dulcimer

AUŠRINE GARSONAITE TRADITIONAL PLAY OF HAMMERED DULCIMER A SELF-STUDY BOOK TRADITIONAL PLAY OF HAMMERED DULCIMER Turinys About the book ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 A Brief Overview of the History of Traditional Music: What Has Changed Over Time? .................................................................................................................... 3 The Dulcimer: Then and Now .................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter One: General Knowledge and Striking Strings in a Row 1.1. Correctly Positioning the Dulcimer and Holding the Hammers; First Sounds ....................................... 10 1.2. Playing on the Left Side of the Treble Bridge 1.2.1. First Compositions in A Major ................................................................................................................. 15 1.2.2. Playing Polka in D ........................................................................................................................................ 17 1.3. Playing on the Right Side of the Treble Bridge 1.3.1. Performing Compositions You Already Know in D Major ............................................................. 20 1.3.2. Performing a Composition You Already Know in G Major ............................................................ 22 1.4. Playing on the Left Side of the Bass Bridge -

The Influence of Bulgarian Folk Music on Petar Christoskov's Suites And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Louisiana State University Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2004 The influence of Bulgarian folk music on Petar Christoskov's Suites and Rhapsodies for solo violin Blagomira Paskaleva Lipari Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lipari, Blagomira Paskaleva, "The influence of Bulgarian folk music on Petar Christoskov's Suites and Rhapsodies for solo violin" (2004). LSU Major Papers. 47. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/47 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF BULGARIAN FOLK MUSIC ON PETAR CHRISTOSKOV’S SUITES AND RHAPSODIES FOR SOLO VIOLIN Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The Department of Music by Blagomira Paskaleva Lipari B. M., State Academy of Music, Sofia, Bulgaria, June 1996 M. M., Louisiana State University, May 1998 August, 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project could not have been possible without the support and encouragement of several people. Thanks to my violin professor Kevork Mardirossian for providing the initial inspiration for this project and for his steady guidance throughout the course of its completion. -

The 'Adaptability' of the Balalaika: an Ethnomusicological Investigation Of

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses Undergraduate Theses 2015 The ‘Adaptability’ of the Balalaika: An Ethnomusicological Investigation of the Russian Traditional Folk Instrument Nicolas Chlebak University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses Recommended Citation Chlebak, Nicolas, "The ‘Adaptability’ of the Balalaika: An Ethnomusicological Investigation of the Russian Traditional Folk Instrument" (2015). UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses. 14. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses/14 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. !1 of !71 The ‘Adaptability’ of the Balalaika: An Ethnomusicological Investigation of the Russian Traditional Folk Instrument Nicolas Chlebak The University of Vermont’s German and Russian Department Thesis Advisor: Kevin McKenna !2 of !71 INTRODUCTION According to the Hornbostel-Sachs system of characterizing instruments, the balalaika is considered a three stringed, triangular lute, meaning its strings are supported by a neck and a bridge that rest over a resonating bout or chamber, like a guitar or violin.1 Many relegate the balalaika solely to its position as the quintessential icon of traditional Russian music. Indeed, whether in proverbs, music, history, painting or any number of other Russian cultural elements, the balalaika remains a singular feature of popular recognition. Pity the student trying to find a Russian tale that doesn’t include a balalaika-playing character. -

Instrument Glossary

AGA KHAN TRUST FOR CULTURE Music Initiative in Central Asia Instrument Glossary 1 2 Glossary of Instruments Choor Chopo Choor Daf Dayra Choor Chopo Choor Daf End-blown flute made from A clay ocarina with 3-6 holes A small frame drum with reed or wood with four or found in southern Kyrgyzstan jingles used to accompany five holes. Under various and most commonly played both popular and classical names and in various sizes, by children. There is music in Azerbaijan. such end-blown flutes are evidence that horse herders widespread among Inner used ocarinas as signalling Dap Asian pastoralists, e.g., tsuur instruments in thick forests, (Mongolian), chuur (Tuvan), where they would often graze Uyghur name for a frame sybyzghy (Kazakh), and kurai their horses at night. drum. (Bashkir). Dayra A frame drum with jingles, commonly played by both men and women among sedentary populations in Central Asia. 3 3 Dombra Dutar Garmon Kemanche Dombra Dutar Ghijak Refers to different types of Designates different kinds Round-bodied spike fiddle two-stringed long-necked of two-stringed long- with 3 or 4 metal strings and lutes, best known of which necked fretted lutes among a short, fretless neck used by is the Kazakh dombra – a Uzbeks, Tajiks, Turkmens, Uzbeks, Tajiks, Turkmens, and fretted lute that is considered Qaraqalpaks, Uyghurs, and Qaraqalpaks. Kazakhstan’s national other groups. instrument. Its large and Kemanche varied repertory centres Garmon around solo instrumental Spike fiddle identical to a pieces, known as kui, which, A small accordion used in the ghijak, important in Iranian like the analogous Caucasus and among female and Azeri classical music and Kyrgyz kuu, are typically wedding entertainers known in the popular music of Iran. -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

Northern Junket, Vol. 11, No. 7

OTK JAM Artf^Jd page Take it Or Leave It .. - ~ ~ - 1 jk Square Dance Foundation - 2 The Three G f s of Square Dancing ~ ^ The Folk Music of Sweden - 6 ^ Quickies -..—.-.*-* - 17 L, Wiy Blame the Fids? 2. Dancing Is An Expression 3. is This the Way Yon Want It? Murphy's Laws - ~ - - — 2f News -------21 Square Dance Four In Line You Travel - 2b Contra Dance - - Long Valley - 25 Folk Demce Zi^uener Polka - 27 Folk Song The Parting Glass - - 27 ' More News - - - ^ 28 Book Reviews *.*.--- 2} Record Reviews - * - 31 More News - - -32 It f s Fun To Hunt * - 33 Painless Folklore - - 38 Colonial Folklore - ^1 Remember When? - ~ kk Old-Timers' Corner - ^5 Good Food - - ^7 Cranberry Ham Slice Blueberry Buckle ' T 4 K E IT OR LEAVE IT Word is trickling in that a great many square dance clubs plan to pat on at least one night r s pro- gram during the coming months of our -.*• ,/t,A>v—Cs f T country s Bi-Centennial . I m proud of them wherever they may "be. And on the same line of thought there will, hopefully, he a revival in interest of dancing to live music. It is already happening here in the East especially at our festivals, conventions and BIG- dances. To me, that is another positive" bit of news. There are unt old thou- sands of young musicians in the country and some of them are sq-uare dancers; the law of averages makes it so! Teach some of the young people a few square dance tunes and let them play them a few times for your club dances.