The Evolution of Syncopation and Improvising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Making Mistakes

The Art of Making Mistakes Misha Alperin Edited by Inna Novosad-Maehlum Music is a creation of the Universe Just like a human being, it reflects God. Real music can be recognized by its soul -- again, like a person. At first sight, music sounds like a language, with its own grammatical and stylistic shades. However, beneath the surface, music is neither style nor grammar. There is a mystery hidden in music -- a mystery that is not immediately obvious. Its mystery and unpredictability are what I am seeking. Misha Alperin Contents Preface (by Inna Novosad-Maehlum) Introduction Nothing but Improvising Levels of Art Sound Sensitivity Fairytales and Fantasy Music vs Mystery Influential Masters The Paradox: an Improvisation on the 100th Birthday of the genius Richter Keith Jarrett Some thoughts on Garbarek (with the backdrop of jazz) The Master on the Pedagogy of Jazz Improvisation as a Way to Oneself Main Principles of Misha's Teachings through the Eyes of His Students Words from the Teacher to his Students Questions & Answers Creativity: an Interview (with Inna Novosad-Maehlum) About Infant-Prodigies: an Interview (with Marina?) One can Become Music: an Interview (with Carina Prange) Biography (by Inna Novosad-Maehlum) Upbringing The musician’s search Alperin and Composing Artists vs. Critics Current Years Reflections on the Meaning of Life Our Search for Answers An Explanation About Formality Golden Scorpion Ego Discography Conclusion: The Creative Process (by Inna Novosad-Maehlum) Preface According to Misha Alperin, human life demands both contemplation and active involvement. In this book, the artist addresses the issues of human identity and belonging, as well as those of the relationship between music and musician. -

S Y N C O P a T I

SYNCOPATION ENGLISH MUSIC 1530 - 1630 'gentle daintie sweet accentings1 and 'unreasonable odd Cratchets' David McGuinness Ph.D. University of Glasgow Faculty of Arts April 1994 © David McGuinness 1994 ProQuest Number: 11007892 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007892 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 10/ 0 1 0 C * p I GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ERRATA page/line 9/8 'prescriptive' for 'proscriptive' 29/29 'in mind' inserted after 'his own part' 38/17 'the first singing primer': Bathe's work was preceded by the short primers attached to some metrical psalters. 46/1 superfluous 'the' deleted 47/3,5 'he' inserted before 'had'; 'a' inserted before 'crotchet' 62/15-6 correction of number in translation of Calvisius 63/32-64/2 correction of sense of 'potestatis' and case of 'tactus' in translation of Calvisius 69/2 'signify' sp. 71/2 'hierarchy' sp. 71/41 'thesis' for 'arsis' as translation of 'depressio' 75/13ff. Calvisius' misprint noted: explanation of his alterations to original text clarified 77/18 superfluous 'themselves' deleted 80/15 'thesis' and 'arsis' reversed 81/11 'necessary' sp. -

The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes In

THE USE OF THE POLISH FOLK MUSIC ELEMENTS AND THE FANTASY ELEMENTS IN THE POLISH FANTASY ON ORIGINAL THEMES IN G-SHARP MINOR FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA OPUS 19 BY IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI Yun Jung Choi, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Choi, Yun Jung, The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes in G-sharp Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 105 pp., 5 tables, 65 examples, references, 97 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to address performance issues in the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, by examining characteristics of Polish folk dances and how they are incorporated in this unique work by Paderewski. The study includes a comprehensive history of the fantasy in order to understand how Paderewski used various codified generic aspects of the solo piano fantasy, as well as those of the one-movement concerto introduced by nineteenth-century composers such as Weber and Liszt. Given that the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, as well as most of Paderewski’s compositions, have been performed more frequently in the last twenty years, an analysis of the combination of the three characteristic aspects of the Polish Fantasy, Op.19 - Polish folk music, the generic rhetoric of a fantasy and the one- movement concerto - would aid scholars and performers alike in better understanding the composition’s engagement with various traditions and how best to make decisions about those traditions when approaching the work in a concert setting. -

4 Classical Music's Coarse Caress

The End of Early Music This page intentionally left blank The End of Early Music A Period Performer’s History of Music for the Twenty-First Century Bruce Haynes 1 2007 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2007 by Bruce Haynes Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Haynes, Bruce, 1942– The end of early music: a period performer’s history of music for the 21st century / Bruce Haynes. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-518987-2 1. Performance practice (Music)—History. 2. Music—Interpretation (Phrasing, dynamics, etc.)—Philosophy and aesthetics. I. Title. ML457.H38 2007 781.4′309—dc22 2006023594 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper This book is dedicated to Erato, muse of lyric and love poetry, Euterpe, muse of music, and Joni M., Honored and Honorary Doctor of broken-hearted harmony, whom I humbly invite to be its patronesses We’re captive on the carousel of time, We can’t return, we can only look behind from where we came. -

Page | 1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. WAYNE SHORTER NEA Jazz Master (1998) Interviewee: Wayne Shorter (August 25, 1933-) Interviewer: Larry Appelbaum and audio engineer Ken Kimery Dates: September 24, 2012 Depository: Archives Center, National Music of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Description: Transcript. 26 pp. Shorter: ...his first three months’ royalty on “Sunny”... It was something... He didn’t have to play the bass. He said, “I’m not playing the bass...” He played in this club, at a restaurant... They’d shot a long scene in there, and did the...well, the thing that was...the Billy Strayhorn thing...you know, that Duke Ellington recorded... “Something in Paris.” [SINGS REFRAIN] Appelbaum: From An American In Paris? Shorter: [CONTINUES TO SING REFRAIN] That song that a lot of singers find hard to sing. Appelbaum: “Lush Life.” Shorter: “Lush Life.” There was some stuff in there. And Shawna(?—0:54) was playing the piano... She was between takes and everything. She was playing...she’s... Appelbaum: She can play. Shorter: Yeah. And tap dancing and all that. But she was like sand-dancing, and waiting for things and all that. I said, “Hey, why don’t you put her in...” Appelbaum: Did Ben Tucker co-write “I’m Comin’ Home, Baby”? Shorter: Ok. He wrote it. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] Page | 1 Appelbaum: Oh, yeah? Shorter: Do you remember the mechanicals, “Notice Of Use” thing... There was something about that. -

How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Kane, Julie Ellen, "How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6892. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6892 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been rqxroduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directfy firom the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiice, vdiile others may be from any typ e o f com pater printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^innm g at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

How to Incorporate Bebop Into Your Improvisation by Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics

How to Incorporate Bebop into Your Improvisation By Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics • Bebop Characteristics & Style • Scales & Arpeggios • Exercises & Patterns • Articulations & Accents • Listening Bebop Characteristics & Style • Developed in the early to mid 1940’s • Medium to fast tempos • Rapid chord progressions / changes • Instrumental “virtuosity” • Simple to complex harmony - altered chords / substitutions • Dominant syncopation of rhythms • New melodies over existing chord changes - Contrafacts Scales & Arpeggios • Scales and arpeggios are the building blocks for harmony • Use of the half-step interval and rapid arpeggiation are characteristic of bebop playing • Because bebop is often played at a fast tempo with rapidly changing chords, it’s crucial to practice your scales and arpeggios in ALL KEYS! Scales & Arpeggios • Scales you should be familiar with: • Major Scale - Pentatonic: 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 • Minor Scales - Pentatonic: 1, b3, 4, 5, b7; Natural Minor, Dorian Minor, Harmonic Minor, Melodic Minor • Dominant Scales - Mixolydian Mode, Bebop Scales, 5th Mode of Harmonic Minor (V7b9), Altered Dominant / Diminished Whole Tone (V7alt, b9#9b13), Dominant Diminished / Diminished starting with a half step (V7b9#9 with #11, 13) • Half-diminished scale - min7b5 (7th mode of major scale) • Diminished Scale - Starting with a whole step (WHWHWHWH) Scales & Arpeggios • Chords and Arpeggios to work in all keys: • Major triad, Maj6/9, Maj7, Maj9, Maj9#11 • Minor triad, m6/9, m7, m9, m11, minMaj7 • Dominant 7ths • Natural extensions - 9th, 13th -

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

BOP HARMONY by Contrast with the Earliest Jazz Musicians, Bop Musicians Did More Than Embellish a Song

Jazz Styles Gridley Eleventh Edition Jazz Styles Mark C. Gridley Eleventh Edition ISBN 978-1-29204-259-6 9 781292 042596 ISBN 10: 1-292-04259-1 ISBN 13: 978-1-292-04259-6 Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate Harlow Essex CM20 2JE England and Associated Companies throughout the world Visit us on the World Wide Web at: www.pearsoned.co.uk © Pearson Education Limited 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying in the United Kingdom issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. The use of any trademark in this text does not vest in the author or publisher any trademark ownership rights in such trademarks, nor does the use of such trademarks imply any affi liation with or endorsement of this book by such owners. ISBN 10: 1-292-04259-1 PEARSON® ISBN 13: 978-1-292-04259-6 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Printed in the United States of America Copyright_Pg_7_24.indd 1 7/29/13 11:28 AM uring the 1940s, a number of adventuresome D musicians showed the effects of studying the advanced swing era styles of saxophonists Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young, pianists Art Tatum and Nat Cole, trumpeter Roy Eldridge, guitarist Charlie Christian, and the Count Basie rhythm section. -

The Development of Musical Improvisation in Second Grade Children

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Graduate Research Papers Student Work 2011 The development of musical improvisation in second grade children Akiko Yoshizawa University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2011 Akiko Yoshizawa Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/grp Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Music Education Commons Recommended Citation Yoshizawa, Akiko, "The development of musical improvisation in second grade children" (2011). Graduate Research Papers. 256. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/grp/256 This Open Access Graduate Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Research Papers by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The development of musical improvisation in second grade children Abstract The purpose of this qualitative case study was to investigate if second-grade children could develop a solo improvisation on an Orff xylophone. Participants were five African-American children who attended a model school that followed an inquiry-based approach curriculum. These children also had a chance to learn music from a faculty and the researcher, who had been exploring constructivist methods of teaching music, with a special emphasis on invented songs, instruments, and notations. The three-day study focused on how children were able to create a solo improvisation. The study was guided by the following questions: (1) Can second grade children develop improvisations on a song they have just learned? (2) What kind of improvisations do they develop? (3) Can second-grade children analyze their own improvisations? If so, how do they describe them? In order to analyze their level of musical complexity, a coding, based on Music Educators National Conference (MENC) K-4 performance standard, was developed to analyze the progression of children's improvisation. -

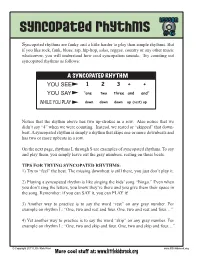

Syncopated Rhythms #6

lesson Syncopated rhythms #6 Syncopated rhythms are funky and a little harder to play than simple rhythms. But if you like rock, funk, blues, rap, hip-hop, salsa, reggae, country or any other music whatsoever, you will understand how cool syncopation sounds. Try counting out syncopated rhythms as follows: A SYNCOPATED RHYTHM YOU SEE 1 2 3 + + YOU SAY “one two three and and” WHILE YOU PLAY down down down up (rest) up Notice that the rhythm above has two up-strokes in a row. Also notice that we didn’t say “4” when we were counting. Instead, we rested or “skipped” that down- beat. A syncopated rhythm is simply a rhythm that skips one or more downbeats and has two or more upbeats in a row. On the next page, rhythms L through S are examples of syncopated rhythms. To say and play them, you simply leave out the gray numbers, resting on those beats. TIPS FOR TRYING SYNCOPATED RHYTHMS: 1) Try to “feel” the beat. The missing downbeat is still there, you just don’t play it. 2) Playing a syncopated rhythm is like singing the kids’ song “Bingo.” Even when you don’t sing the letters, you know they’re there and you give them their space in the song. Remember: if you can SAY it, you can PLAY it! 3) Another way to practice is to say the word “rest” on any gray number. For example on rhythm L: “One, two and rest and four. One, two and rest and four…” 4) Yet another way to practice is to say the word “skip” on any gray number. -

English Lute Manuscripts and Scribes 1530-1630

ENGLISH LUTE MANUSCRIPTS AND SCRIBES 1530-1630 An examination of the place of the lute in 16th- and 17th-century English Society through a study of the English Lute Manuscripts of the so-called 'Golden Age', including a comprehensive catalogue of the sources. JULIA CRAIG-MCFEELY Oxford, 2000 A major part of this book was originally submitted to the University of Oxford in 1993 as a Doctoral thesis ENGLISH LUTE MANUSCRIPTS AND SCRIBES 1530-1630 All text reproduced under this title is © 2000 JULIA CRAIG-McFEELY The following chapters are available as downloadable pdf files. Click in the link boxes to access the files. README......................................................................................................................i EDITORIAL POLICY.......................................................................................................iii ABBREVIATIONS: ........................................................................................................iv General...................................................................................iv Library sigla.............................................................................v Manuscripts ............................................................................vi Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century printed sources............................ix GLOSSARY OF TERMS: ................................................................................................XII Palaeographical: letters..............................................................xii