An Exploration of Governance and Accountability Issues Within Mutual Organisations: the Case of UK Building Societies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lender Panel List December 2019

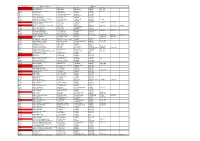

Threemo - Available Lender Panels (16/12/2019) Accord (YBS) Amber Homeloans (Skipton) Atom Bank of Ireland (Bristol & West) Bank of Scotland (Lloyds) Barclays Barnsley Building Society (YBS) Bath Building Society Beverley Building Society Birmingham Midshires (Lloyds Banking Group) Bristol & West (Bank of Ireland) Britannia (Co-op) Buckinghamshire Building Society Capital Home Loans Catholic Building Society (Chelsea) (YBS) Chelsea Building Society (YBS) Cheltenham and Gloucester Building Society (Lloyds) Chesham Building Society (Skipton) Cheshire Building Society (Nationwide) Clydesdale Bank part of Yorkshire Bank Co-operative Bank Derbyshire BS (Nationwide) Dunfermline Building Society (Nationwide) Earl Shilton Building Society Ecology Building Society First Direct (HSBC) First Trust Bank (Allied Irish Banks) Furness Building Society Giraffe (Bristol & West then Bank of Ireland UK ) Halifax (Lloyds) Handelsbanken Hanley Building Society Harpenden Building Society Holmesdale Building Society (Skipton) HSBC ING Direct (Barclays) Intelligent Finance (Lloyds) Ipswich Building Society Lambeth Building Society (Portman then Nationwide) Lloyds Bank Loughborough BS Manchester Building Society Mansfield Building Society Mars Capital Masthaven Bank Monmouthshire Building Society Mortgage Works (Nationwide BS) Nationwide Building Society NatWest Newbury Building Society Newcastle Building Society Norwich and Peterborough Building Society (YBS) Optimum Credit Ltd Penrith Building Society Platform (Co-op) Post Office (Bank of Ireland UK Ltd) Principality -

Banking in Cark-In Cartmel

An undated photograph produced by the firm of Woolfall & Eccles (later T M Alexander & Son), architects of the Midland Bank, 119, Station Rd. Cark in Cartmel1 Banking in Cark-in Cartmel In today's high street the bank is becoming a rarity and 2017 will see the closure of another branching the Cartmel Peninsula; the National Westminster Bank in Main Street, Grange over Sands.2The banks are leaving the small market town high street but in the late nineteenth and for the first half of the twentieth century they were part of the local landscape in not only market towns, but even villages and hamlets such as Cark in Cartmel. Until 1826, banks were essentially private merchant banks but the Bank Act of 1826 permitted joint stock banks of issue with unlimited liability to be established. The Lancaster Banking Co. was one such bank which was set up in 1826 and existed until 1907 when it was taken over. For over seventy years, the hamlet of Cark in Cartmel, Cumbria had three banks ; the Lancaster Banking Co. which according to the Bulmer's Directory of 19113 was located at Bank House, Station Rd. and opened initially on Fridays ; the York City and County Banking Co. which became 1 HSBC archives April 18th 2017 2 The Westmorland Gazette, Thursday, March 31st. 2017 3 Bulmer's Directory of 1911. the London and Joint Stock Bank Ltd. was also located at 119 Station Rd. ; and the Bank of Liverpool and Martin's Ltd. which was located opposite at 114 Station Rd. All three banks were characterised by the fact that the banking premises occupied only one room of the building that they occupied and in addition were staffed by one member of staff , which in the case of the Midland and Martin's banks was the bank manager from either the Ulverston or Grange branch. -

Reference Banks / Finance Address

Reference Banks / Finance Address B/F2 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F262 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F57 Abbey National Treasury Services Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F168 ABN Amro Bank 199 Bishopsgate LONDON EC2M 3TY B/F331 ABSA Bank Ltd 52/54 Gracechurch Street LONDON EC3V 0EH B/F175 Adam & Company Plc 22 Charlotte Square EDINBURGH EH2 4DF B/F313 Adam & Company Plc 42 Pall Mall LONDON SW1Y 5JG B/F263 Afghan National Credit & Finance Ltd New Roman House 10 East Road LONDON N1 6AD B/F180 African Continental Bank Plc 24/28 Moorgate LONDON EC2R 6DJ B/F289 Agricultural Mortgage Corporation (AMC) AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER Hampshire SP10 1DE B/F147 AIB Capital Markets Plc 12 Old Jewry LONDON EC2 B/F290 Alliance & Leicester Commercial Lending Girobank Bootle Centre Bridal Road BOOTLE Merseyside GIR 0AA B/F67 Alliance & Leicester Plc Carlton Park NARBOROUGH LE9 5XX B/F264 Alliance & Leicester plc 49 Park Lane LONDON W1Y 4EQ B/F110 Alliance Trust Savings Ltd PO Box 164 Meadow House 64 Reform Street DUNDEE DD1 9YP B/F32 Allied Bank of Pakistan Ltd 62-63 Mark Lane LONDON EC3R 7NE B/F134 Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc 114 Rochester Row LONDON SW1P B/F291 Allied Irish Bank Plc Commercial Banking Bankcentre Belmont Road UXBRIDGE Middlesex UB8 1SA B/F8 Amber Homeloans Ltd 1 Providence Place SKIPTON North Yorks BD23 2HL B/F59 AMC Bank Ltd AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER SP10 1DD B/F345 American Express Bank Ltd 60 Buckingham Palace Road LONDON SW1 W B/F84 Anglo Irish -

Members' Review

Make your MEMBERS’ vote count See inside REVIEW for details & Summary Financial Statement 2020 Always with your interest at heart FURNESS BUILDING SOCIETY MEMBERS’ REVIEW & SUMMARY FINANCIAL STATEMENT 2020 3 CONTENTS Performance Summary 4 Welcome from our Chief Executive 6 Directors’ Report 8-23 Strategic Review 8 Business Review 9-14 Risk Review 15-20 Our People and Members 21-22 The Year Ahead 23 Directors’ Remuneration Report 24-27 Team Biographies 28-30 Independent Auditor’s Statement 31-32 Notice of Annual General Meeting 2021 33 Summary Financial Statement 34-35 WWW.FURNESSSBS.CO.UK 4 PERFORMANCE SUMMARY Financial Strength Profit before tax Total Capital Ratio 22.06% 21.24% £4.11m 20.98% 20.25% 19.23% £3.74m £2.99m £2.35m £1.10m 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Business Summary Retail Share and Deposit Balances Mortgage Balances £1,013.39m £911.10m £920.43m £915.49m £882.49m £824.41m £818.94m £763.68m £738.70m £696.29m 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 FURNESS BUILDING SOCIETY MEMBERS’ REVIEW & SUMMARY FINANCIAL STATEMENT 2020 5 WWW.FURNESSSBS.CO.UK 6 Welcome from our Chief Executive Dear Member, In the remarkable year which also saw us reach the end of the Brexit transitional Let me begin by sending period on 31 December 2020, we’ve sincere regards to all also continued to support local charities, our members after community groups and food banks. what has been an This includes £198,000 in affinity accounts incredibly difficult year payments on your behalf, of which for everybody. -

Full Proposal for Establishing a New Unitary Authority for Barrow, Lancaster and South Lakeland

Full proposal for establishing a new unitary authority for Barrow, Lancaster and South Lakeland December 2020 The Bay Council and North Cumbria Council Proposal by Barrow Borough Council, Lancaster City Council and South Lakeland District Council Foreword Dear Secretary of State, Our proposals for unitary local government in the Bay would build on existing momentum and the excellent working relationships already in place across the three district Councils in the Bay area. Together, we can help you deliver a sustainable and resilient local government solution in this area that delivers priority services and empowers communities. In line with your invitation, and statutory guidance, we are submitting a Type C proposal for the Bay area which comprises the geographies of Barrow, Lancaster Cllr Ann Thomson Sam Plum and South Lakeland councils and the respective areas of the county councils of Leader of the Council Chief Executive Cumbria and Lancashire. This is a credible geography, home to nearly 320,000 Barrow Borough Council Barrow Borough Council people, most of whom live and work in the area we represent. Having taken into account the impact of our proposal on other local boundaries and geographies, we believe creating The Bay Council makes a unitary local settlement for the remainder of Cumbria more viable and supports consideration of future options in Lancashire. Partners, particularly the health service would welcome alignment with their footprint and even stronger partnership working. Initial discussions with the Police and Crime Commissioners, Chief Officers and lead member for Fire and Cllr Dr Erica Lewis Kieran Keane Rescue did not identify any insurmountable barriers, whilst recognising the need Leader of the Council Chief Executive for further consultation. -

UK Property Finance: Expats & Overseas Residents

UK property finance: Expats & Overseas Residents +44 (0) 20 3786 7270 [email protected] 2 Financing UK property The mortgage market has become increasingly As a result, it’s no longer the major banks who challenging for anyone based outside the UK specialise in UK mortgages for expats and other seeking finance on UK property. A few years overseas residents. Instead, it’s a range of smaller, ago, major players such as Lloyds International, niche lenders that have the appetite to lend for a Barclays, Bank of Scotland and RBS International UK purchase or remortgage. provided competitive and convenient finance to expats and other overseas residents. However, with no branches or local representation, accessing these lenders can be Recently, things have changed. The financial crisis tough. That’s where Altura comes in. With strong saw major lenders retreat to domestic, UK-based relationships with a wide range of private banks, clients. New regulations governing residential challenger banks and regional building societies, mortgages have resulted in a forensic focus on we can find the right lender for you; whatever affordability and an increasing requirement for your situation, whether for investment or as a advice. Buy to Let changes have led to tougher future home. rental stress tests and greater underwriting demands for portfolio landlords. Technology has had an impact too. Major lenders are increasingly relying on algorithms to make automated lending decisions, much of which is +44 (0) 20 3786 7270 reliant on a ‘credit footprint’ via a credit agency [email protected] such as Experian or Equifax. If, however, you’ve been in Hong Kong, Dubai or New York for the last www.alturafin.com ten years, you’re not going to show much on an Experian report. -

Lenders Who Have Signed up to the Agreement

Lenders who have signed up to the agreement A list of the lenders who have committed to the voluntary agreement can be found below. This list includes parent and related brands within each group. It excludes lifetime and pure buy-to-let providers. We expect more lenders to commit over the coming months. 1. Accord Mortgage 43. Newcastle Building Society 2. Aldermore 44. Nottingham Building Society 3. Bank of Ireland UK PLC 45. Norwich & Peterborough BS 4. Bank of Scotland 46. One Savings Bank Plc 5. Barclays UK plc 47. Penrith Building Society 6. Barnsley Building Society 48. Platform 7. Bath BS 49. Principality Building Society 8. Beverley Building Society 50. Progressive Building Society 9. Britannia 51. RBS plc 10. Buckinghamshire BS 52. Saffron Building Society 11. Cambridge Building Society 53. Santander UK Plc 12. Chelsea Building Society 54. Scottish Building Society 13. Chorley Building Society 55. Scottish Widows Bank 14. Clydesdale Bank 56. Skipton Building Society 15. The Co-operative Bank plc 57. Stafford Railway Building Society 16. Coventry Building Society 58. Teachers Building Society 17. Cumberland BS 59. Tesco Bank 18. Danske Bank 60. Tipton & Coseley Building Society 19. Darlington Building Society 61. Trustee Savings Bank 20. Direct Line 62. Ulster Bank 21. Dudley Building Society 63. Vernon Building Society 22. Earl Shilton Building Society 64. Virgin Money Holdings (UK) plc 23. Family Building Society 65. West Bromwich Building Society 24. First Direct 66. Yorkshire Bank 25. Furness Building Society 67. Yorkshire Building Society 26. Halifax 27. Hanley Economic Building Society 28. Hinckley & Rugby Building Society 29. HSBC plc 30. -

Grange-Over-Sands Civic Society

MAR 17 range now ISSUE 307 - G grangenow.co.uk Cartmel Priory is ‘Top of the Class’CLASS OF 2016 digital aerial & Shirley M. Evans LL.B satellite specialists ALAN SPEIRS Solicitor a Domestic Digital & Aerial Upgrades GENERAL BUILDER a Commerical Systems - Design & Install 5 Lowther Gardens, SPECIALISING IN RESIDENTIAL SALES ALL BUILDING WORK Grange-over-Sands, AND PROPERTY LETTINGS Sky Installation & Repairs For your FREE market appraisal contact Home Sound & Vision Systems UNDERTAKEN email: [email protected] our Grange Office on 015395 33302 r r Reg No: 18265860 Roofing, Plastering, New Builds, T: 015395 35208 F: 015395 34820 We also undertake Valuations FREESAT HD FREEVIEW for all purposes including Probate, Renovations & Joinery Work Inheritance Tax and Insurance d Grange 015395 32792 Tel: 015395 34403 “Here to Help” London House, Main St, Grange-over-Sands LA11 6DP d Mobile: 07798 697880 www.michael-cl-hodgson.co.uk Mobile: 07956 006 502 We are a family run business, Portabello with over 25 years experience. D Blinds & Curtains We pride ourselves on our reliable, PL Motors prompt and personal service. • Faux wooden interior shutters MoT & Service Centre only a three week delivery - P TYRES manufactured in the UK Free Local Collection AT TRADE PRICES • Venetian, roller, roman and & Delivery Why travel to Kendal? Save on fuel vertical blinds P and come to Flookburgh. FOR ALL YOUR SIGN REQUIREMENTS • Extensive, beautiful range of MoT’s while you wait made to measure curtains or by appointment For sizes & prices ring Leeroy or Deano Vehicle graphics • Conservatory blind specialists Love your 01524 702 111 P Free courtesy local Window graphics www.portabello.net • Approved Velux blind dealers Garage 015395 58920 cars & vans Mile Road Garage, Moor Lane, Flookburgh. -

Buckinghal\Fshire. [KELLY's JOB Masters-Continueo

270 JOB BUCKINGHAl\fSHIRE. [KELLY'S JOB MAsTERs-continueo. LACQUER MAKERS. Harris Matthew Major (to R G. W_ Clode Herbert,Fenny Stratford,Bletch- Rhus &; Co. Lim. Oxford rd. Wycmbe Tyringham esq.), Tyringham, New- ley Station port Pagnell Dancer W. Gerrard's Cross R.S.O LADDER MAKER. Harrison Cyril H. G. (to the Earl of Darvell C.I89Waterside,Cheshm.R'.S.0 Palmer Edwin; Palmer's wire sup- Roseb~~y), Ledbum, Leightn.Bzz!d *Fisher F. G. 42 Walton st. Aylesbury ported travelling cradles, 250 West- Hart PhIhp (to Leop?ld de.Rothsc.hild *Goddard William Edwd. Iver,Uxbdg minster Bridge road, London SE esq. J.P.), Moor hIlls, Wrng, LeIgh- Gough Wm. J. Market sq. Buckinghm ton Buzzard *Hall J. &; Son,Bumham, Maidenhead. LADIES' OUTFITTERS. Hay Colin (to Lord Addington), See advert See Outfitters Ladies'. Addington, Winslow Hawley Thos.High st. Stony Stratford Hepworth Montagu (to Lord Boston), Higgs W. & Son, Willow rd.Aylesbury LAGER BEER IMPORTERS. '1'he Priory, Hedsor, Bourne EndS.O Holland Joseph Senior, High street, Jacob F. &; Co. Jacob's Pilsener lager Hervey-Bathurst Fenton (to Dowager Wendover, Tring. See advert beer importers & bottlers, 77, 79 & Lady de Rothschild), Aston Clinton, tHowe Robert, Aston Clinton, Tring 81 Theobald's road, London WC Tring Innocent Lewis William Samuel,Manor Hubbard Frederick Joseph (to Alfred hotel, Datchet, Windsor LAND AGENTS. Charles de Rothschild esq.), Halton Lane T. F. High street, Beaconsfield See Agents Land, House & Estate. cottage, Halton, Tring R.S.O. ; station,Wooburn Gn.G.W.R James George Tubb (to the Earl of *Lewis Geo. -

MORTGAGE CREDIT DIRECTIVE General Information for Regulated Mortgages

In branch 0800 072 1100 saffronbs.co.uk MORTGAGE CREDIT DIRECTIVE General Information for Regulated Mortgages Saffron Building Society is authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority (Financial Services Register no. 100015) except for Commercial and Investment Buy to Let Mortgages and Will Writing. SBS_MCD_22.3.2016_a The following contains general information we are required to make available in relation to regulated mortgage contracts. 1. Address Saffron Building Society 1A Market Street, Saffron Walden, Essex CB10 1HX 2.Purpose of credit We offer Mortgages which can be used for house purchases, re-mortgage, further advance, building your own home, or consumer buy-to-let. 3.Security Mortgages offered by Saffron Building Society must be secured by a first legal charge or mortgage on a UK property. 4.Duration Our Mortgages are offered over a minimum repayment term of 5 years and a maximum term of 40 years. This does not apply to Self Build Mortgages. 5.Saffron Building Society offers the following types of interest rate: Fixed: A fixed rate mortgage provides the comfort of fixed mortgage payments until an agreed date, no matter what happens to interest rates. • Monthly Payments: these are fixed for the duration of the fixed rate period, and because the interest rate doesn’t vary, monthly payments will remain the same regardless of what happens to interest rates. • At the end of any fixed rate period the borrower will automatically move onto a variable rate. The borrower can choose to stay on this rate, or could apply for a new fixed or discounted mortgage available at that time. -

OSCRE Industry Alliance Organizations Synopsis

OSCRE Connecting the Real Estate Industry ALLIANCE ORGANIZATION SYNOPSIS OSCRE is the trading name of OSCRE Americas Inc., part of the OSCRE International global network supporting the Americas. OSCRE Americas Inc. is registered in Washington, District of Columbia. E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.oscre.org © 2003, 2004 OSCRE International. All Rights Reserved. Version History 1.0 Andy Fuhrman March 29, 2004 Document Creation 1.1 Andy Fuhrman April 4, 2004 Incorporated feedback from OSCRE International Executive Board 1.2 Chris Lees May 26, 2004 Section 2: Verbiage Modification OSCRE International OSCRE Americas PISCES Limited 2020 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW 7-8 Greenland Place Box #1024 LONDON, NW1 0AP Washington, DC 20006 www.pisces.co.uk www.oscre.org ALLIANCE ORGANIZATION SYNOPSIS © 2003-2004 OSCRE International. All Rights Reserved. 2 of 46 Contents 1 Mission ................................................................................................... 4 2 Industry Focus ......................................................................................... 4 3 Methodology ............................................................................................ 4 4 Document Purpose ................................................................................... 5 5 About OSCRE........................................................................................... 5 5.1 OSCRE International Executive Board Members ..................................... 6 5.2 Projected OSCRE Timeline ................................................................. -

Your Guide to Self Build Mortgages

Your guide to Self Build Mortgages Helping you build the home of your dreams In branch 0800 072 1100 saffronbs.co.uk CONTENTS The difference between a traditional mortgage 1 and a Self Build mortgage How a Saffron Self Build mortgage can help you 1 How much can you borrow? 1 - 2 How does the Saffron Self Build Mortgage work? 3 Next steps 3 What happens when your self build project has been 3 completed? A few final points worth considering 4 Further Information 4 Useful additional sources of information 5 Investing time and effort into building your own home enables you to specify and create your dream home from scratch, rather than looking for the next best thing on the open market. Every year, around 12,000 people build their own homes in the UK, including newly constructed 1. Purchasing the land properties, barn conversions and renovations. 2. Initial project costs and laying foundations You don’t need a detailed understanding of the house-building industry or processes. What you do 3. Construction to wall plate level (and timber need is professional guidance from an architect or frame erected, if appropriate) project manager and, most importantly, you need to maintain a tight control over your finances. 4. Building made wind and watertight Financing a self build project is not the same 5. First fix and plastering as buying an existing home with a traditional mortgage. This guide has therefore been written 6. Second fix through to completion to explain how Saffron’s specialist Self Build Mortgage works and how you can ensure you It’s important to have a detailed cashflow budget keep your finances on-track as you build your new prepared at the outset, so that you know precisely home.