Carnegie Institution of Washington Support for Mathematics from 1902 to 1921

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics Is a Gentleman's Art: Analysis and Synthesis in American College Geometry Teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2000 Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K. Ackerberg-Hastings Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Ackerberg-Hastings, Amy K., "Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 " (2000). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 12669. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/12669 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margwis, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 10:06:53AM Via Free Access 268 Revue De Synthèse : TOME 139 7E SÉRIE N° 3-4 (2018) Chercheur Pour IBM

REVUE DE SYNTHÈSE : TOME 139 7e SÉRIE N° 3-4 (2018) 267-288 brill.com/rds A Task that Exceeded the Technology: Early Applications of the Computer to the Lunar Three-body Problem Allan Olley* Abstract: The lunar Three-Body problem is a famously intractable problem of Newtonian mechanics. The demand for accurate predictions of lunar motion led to practical approximate solutions of great complexity, constituted by trigonometric series with hundreds of terms. Such considerations meant there was demand for high speed machine computation from astronomers during the earliest stages of computer development. One early innovator in this regard was Wallace J. Eckert, a Columbia University professor of astronomer and IBM researcher. His work illustrates some interesting features of the interaction between computers and astronomy. Keywords: history of astronomy – three body problem – history of computers – Wallace J. Eckert Une tâche excédant la technologie : l’utilisation de l’ordinateur dans le problème lunaire des trois corps Résumé : Le problème des trois corps appliqué à la lune est un problème classique de la mécanique newtonienne, connu pour être insoluble avec des méthodes exactes. La demande pour des prévisions précises du mouvement lunaire menait à des solutions d’approximation pratiques qui étaient d’une complexité considérable, avec des séries tri- gonométriques contenant des centaines de termes. Cela a très tôt poussé les astronomes à chercher des outils de calcul et ils ont été parmi les premiers à utiliser des calculatrices rapides, dès les débuts du développement des ordinateurs modernes. Un innovateur des ces années-là est Wallace J. Eckert, professeur d’astronomie à Columbia University et * Allan Olley, born in 1979, he obtained his PhD-degree from the Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science Technology (IHPST), University of Toronto in 2011. -

Janko's Sporadic Simple Groups

Janko’s Sporadic Simple Groups: a bit of history Algebra, Geometry and Computation CARMA, Workshop on Mathematics and Computation Terry Gagen and Don Taylor The University of Sydney 20 June 2015 Fifty years ago: the discovery In January 1965, a surprising announcement was communicated to the international mathematical community. Zvonimir Janko, working as a Research Fellow at the Institute of Advanced Study within the Australian National University had constructed a new sporadic simple group. Before 1965 only five sporadic simple groups were known. They had been discovered almost exactly one hundred years prior (1861 and 1873) by Émile Mathieu but the proof of their simplicity was only obtained in 1900 by G. A. Miller. Finite simple groups: earliest examples É The cyclic groups Zp of prime order and the alternating groups Alt(n) of even permutations of n 5 items were the earliest simple groups to be studied (Gauss,≥ Euler, Abel, etc.) É Evariste Galois knew about PSL(2,p) and wrote about them in his letter to Chevalier in 1832 on the night before the duel. É Camille Jordan (Traité des substitutions et des équations algébriques,1870) wrote about linear groups defined over finite fields of prime order and determined their composition factors. The ‘groupes abéliens’ of Jordan are now called symplectic groups and his ‘groupes hypoabéliens’ are orthogonal groups in characteristic 2. É Émile Mathieu introduced the five groups M11, M12, M22, M23 and M24 in 1861 and 1873. The classical groups, G2 and E6 É In his PhD thesis Leonard Eugene Dickson extended Jordan’s work to linear groups over all finite fields and included the unitary groups. -

Publications of Members, 1930-1954

THE INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY PUBLICATIONS OF MEMBERS 1930 • 1954 PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY . 1955 COPYRIGHT 1955, BY THE INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, PRINCETON, N.J. CONTENTS FOREWORD 3 BIBLIOGRAPHY 9 DIRECTORY OF INSTITUTE MEMBERS, 1930-1954 205 MEMBERS WITH APPOINTMENTS OF LONG TERM 265 TRUSTEES 269 buH FOREWORD FOREWORD Publication of this bibliography marks the 25th Anniversary of the foundation of the Institute for Advanced Study. The certificate of incorporation of the Institute was signed on the 20th day of May, 1930. The first academic appointments, naming Albert Einstein and Oswald Veblen as Professors at the Institute, were approved two and one- half years later, in initiation of academic work. The Institute for Advanced Study is devoted to the encouragement, support and patronage of learning—of science, in the old, broad, undifferentiated sense of the word. The Institute partakes of the character both of a university and of a research institute j but it also differs in significant ways from both. It is unlike a university, for instance, in its small size—its academic membership at any one time numbers only a little over a hundred. It is unlike a university in that it has no formal curriculum, no scheduled courses of instruction, no commitment that all branches of learning be rep- resented in its faculty and members. It is unlike a research institute in that its purposes are broader, that it supports many separate fields of study, that, with one exception, it maintains no laboratories; and above all in that it welcomes temporary members, whose intellectual development and growth are one of its principal purposes. -

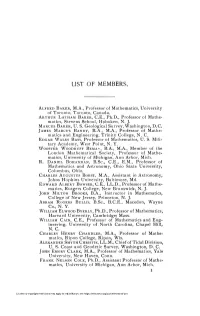

List of Members

LIST OF MEMBERS, ALFRED BAKER, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. ARTHUR LATHAM BAKER, C.E., Ph.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Stevens School, Hpboken., N. J. MARCUS BAKER, U. S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. JAMES MARCUS BANDY, B.A., M.A., Professor of Mathe matics and Engineering, Trinit)^ College, N. C. EDGAR WALES BASS, Professor of Mathematics, U. S. Mili tary Academy, West Point, N. Y. WOOSTER WOODRUFF BEMAN, B.A., M.A., Member of the London Mathematical Society, Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. R. DANIEL BOHANNAN, B.Sc, CE., E.M., Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. CHARLES AUGUSTUS BORST, M.A., Assistant in Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md. EDWARD ALBERT BOWSER, CE., LL.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Rutgers College, New Brunswick, N. J. JOHN MILTON BROOKS, B.A., Instructor in Mathematics, College of New Jersey, Princeton, N. J. ABRAM ROGERS BULLIS, B.SC, B.C.E., Macedon, Wayne Co., N. Y. WILLIAM ELWOOD BYERLY, Ph.D., Professor of Mathematics, Harvard University, Cambridge*, Mass. WILLIAM CAIN, C.E., Professor of Mathematics and Eng ineering, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N. C. CHARLES HENRY CHANDLER, M.A., Professor of Mathe matics, Ripon College, Ripon, Wis. ALEXANDER SMYTH CHRISTIE, LL.M., Chief of Tidal Division, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Washington, D. C. JOHN EMORY CLARK, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. FRANK NELSON COLE, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. -

Oswald Veblen

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES O S W A L D V E B LEN 1880—1960 A Biographical Memoir by S A U N D E R S M A C L ANE Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1964 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. OSWALD VEBLEN June 24,1880—August 10, i960 BY SAUNDERS MAC LANE SWALD VEBLEN, geometer and mathematical statesman, spanned O in his career the full range of twentieth-century Mathematics in the United States; his leadership in transmitting ideas and in de- veloping young men has had a substantial effect on the present mathematical scene. At the turn of the century he studied at Chi- cago, at the period when that University was first starting the doc- toral training of young Mathematicians in this country. He then continued at Princeton University, where his own work and that of his students played a leading role in the development of an outstand- ing department of Mathematics in Fine Hall. Later, when the In- stitute for Advanced Study was founded, Veblen became one of its first professors, and had a vital part in the development of this In- stitute as a world center for mathematical research. Veblen's background was Norwegian. His grandfather, Thomas Anderson Veblen, (1818-1906) came from Odegaard, Homan Con- gregation, Vester Slidre Parish, Valdris. After work as a cabinet- maker and as a Norwegian soldier, he was anxious to come to the United States. -

Academic Genealogy of the Oakland University Department Of

Basilios Bessarion Mystras 1436 Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 Università di Padova 1444 Academic Genealogy of the Oakland University Vittorino da Feltre Marsilio Ficino Cristoforo Landino Università di Padova 1416 Università di Firenze 1462 Theodoros Gazes Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Angelo Poliziano Florens Florentius Radwyn Radewyns Geert Gerardus Magnus Groote Università di Mantova 1433 Università di Mantova Università di Firenze 1477 Constantinople 1433 DepartmentThe Mathematics Genealogy Project of is a serviceMathematics of North Dakota State University and and the American Statistics Mathematical Society. Demetrios Chalcocondyles http://www.mathgenealogy.org/ Heinrich von Langenstein Gaetano da Thiene Sigismondo Polcastro Leo Outers Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Rudolf Agricola Thomas von Kempen à Kempis Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Accademia Romana 1452 Université de Paris 1363, 1375 Université Catholique de Louvain 1485 Università di Firenze 1493 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1478 Mystras 1452 Jan Standonck Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Johannes von Gmunden Nicoletto Vernia Pietro Roccabonella Pelope Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Jean Tagault François Dubois Janus Lascaris Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Matthaeus Adrianus Alexander Hegius Johannes Stöffler Collège Sainte-Barbe 1474 Universität Basel 1477 Universität Wien 1406 Università di Padova Università di Padova Université Catholique de Louvain 1504, 1515 Université de Paris 1516 Università di Padova 1472 Università -

EJC Cover Page

Early Journal Content on JSTOR, Free to Anyone in the World This article is one of nearly 500,000 scholarly works digitized and made freely available to everyone in the world by JSTOR. Known as the Early Journal Content, this set of works include research articles, news, letters, and other writings published in more than 200 of the oldest leading academic journals. The works date from the mid-seventeenth to the early twentieth centuries. We encourage people to read and share the Early Journal Content openly and to tell others that this resource exists. People may post this content online or redistribute in any way for non-commercial purposes. Read more about Early Journal Content at http://about.jstor.org/participate-jstor/individuals/early- journal-content. JSTOR is a digital library of academic journals, books, and primary source objects. JSTOR helps people discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content through a powerful research and teaching platform, and preserves this content for future generations. JSTOR is part of ITHAKA, a not-for-profit organization that also includes Ithaka S+R and Portico. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. PUBLICATIONS OF THE AstronomicalSociety of the Pacific. Vol. XXI. San Francisco, California, April 10, 1909. No. 125 ADDRESS OF THE RETIRING PRESIDENT OF THE SOCIETY, IN AWARDING THE BRUCE MEDAL TO DR. GEORGE WILLIAM HILL. By Charles Burckhalter. The eighthaward of the BruceGold Medal of thisSociety has beenmade to Dr. GeorgeWilliam Hill. To thosehaving understanding of the statutes,and the methodgoverning the bestowal of the medal,it goes without sayingthat it is always worthilybestowed. -

January 2013 Prizes and Awards

January 2013 Prizes and Awards 4:25 P.M., Thursday, January 10, 2013 PROGRAM SUMMARY OF AWARDS OPENING REMARKS FOR AMS Eric Friedlander, President LEVI L. CONANT PRIZE: JOHN BAEZ, JOHN HUERTA American Mathematical Society E. H. MOORE RESEARCH ARTICLE PRIZE: MICHAEL LARSEN, RICHARD PINK DEBORAH AND FRANKLIN TEPPER HAIMO AWARDS FOR DISTINGUISHED COLLEGE OR UNIVERSITY DAVID P. ROBBINS PRIZE: ALEXANDER RAZBOROV TEACHING OF MATHEMATICS RUTH LYTTLE SATTER PRIZE IN MATHEMATICS: MARYAM MIRZAKHANI Mathematical Association of America LEROY P. STEELE PRIZE FOR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT: YAKOV SINAI EULER BOOK PRIZE LEROY P. STEELE PRIZE FOR MATHEMATICAL EXPOSITION: JOHN GUCKENHEIMER, PHILIP HOLMES Mathematical Association of America LEROY P. STEELE PRIZE FOR SEMINAL CONTRIBUTION TO RESEARCH: SAHARON SHELAH LEVI L. CONANT PRIZE OSWALD VEBLEN PRIZE IN GEOMETRY: IAN AGOL, DANIEL WISE American Mathematical Society DAVID P. ROBBINS PRIZE FOR AMS-SIAM American Mathematical Society NORBERT WIENER PRIZE IN APPLIED MATHEMATICS: ANDREW J. MAJDA OSWALD VEBLEN PRIZE IN GEOMETRY FOR AMS-MAA-SIAM American Mathematical Society FRANK AND BRENNIE MORGAN PRIZE FOR OUTSTANDING RESEARCH IN MATHEMATICS BY ALICE T. SCHAFER PRIZE FOR EXCELLENCE IN MATHEMATICS BY AN UNDERGRADUATE WOMAN AN UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT: FAN WEI Association for Women in Mathematics FOR AWM LOUISE HAY AWARD FOR CONTRIBUTIONS TO MATHEMATICS EDUCATION LOUISE HAY AWARD FOR CONTRIBUTIONS TO MATHEMATICS EDUCATION: AMY COHEN Association for Women in Mathematics M. GWENETH HUMPHREYS AWARD FOR MENTORSHIP OF UNDERGRADUATE -

A History of Mathematics in America Before 1900.Pdf

THE BOOK WAS DRENCHED 00 S< OU_1 60514 > CD CO THE CARUS MATHEMATICAL MONOGRAPHS Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Publication Committee GILBERT AMES BLISS DAVID RAYMOND CURTISS AUBREY JOHN KEMPNER HERBERT ELLSWORTH SLAUGHT CARUS MATHEMATICAL MONOGRAPHS are an expression of THEthe desire of Mrs. Mary Hegeler Carus, and of her son, Dr. Edward H. Carus, to contribute to the dissemination of mathe- matical knowledge by making accessible at nominal cost a series of expository presenta- tions of the best thoughts and keenest re- searches in pure and applied mathematics. The publication of these monographs was made possible by a notable gift to the Mathematical Association of America by Mrs. Carus as sole trustee of the Edward C. Hegeler Trust Fund. The expositions of mathematical subjects which the monographs will contain are to be set forth in a manner comprehensible not only to teach- ers and students specializing in mathematics, but also to scientific workers in other fields, and especially to the wide circle of thoughtful people who, having a moderate acquaintance with elementary mathematics, wish to extend their knowledge without prolonged and critical study of the mathematical journals and trea- tises. The scope of this series includes also historical and biographical monographs. The Carus Mathematical Monographs NUMBER FIVE A HISTORY OF MATHEMATICS IN AMERICA BEFORE 1900 By DAVID EUGENE SMITH Professor Emeritus of Mathematics Teacliers College, Columbia University and JEKUTHIEL GINSBURG Professor of Mathematics in Yeshiva College New York and Editor of "Scripta Mathematica" Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA with the cooperation of THE OPEN COURT PUBLISHING COMPANY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS THE OPEN COURT COMPANY Copyright 1934 by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMKRICA Published March, 1934 Composed, Printed and Bound by tClfe QlolUgUt* $Jrr George Banta Publishing Company Menasha, Wisconsin, U. -

Moon-Earth-Sun: the Oldest Three-Body Problem

Moon-Earth-Sun: The oldest three-body problem Martin C. Gutzwiller IBM Research Center, Yorktown Heights, New York 10598 The daily motion of the Moon through the sky has many unusual features that a careful observer can discover without the help of instruments. The three different frequencies for the three degrees of freedom have been known very accurately for 3000 years, and the geometric explanation of the Greek astronomers was basically correct. Whereas Kepler’s laws are sufficient for describing the motion of the planets around the Sun, even the most obvious facts about the lunar motion cannot be understood without the gravitational attraction of both the Earth and the Sun. Newton discussed this problem at great length, and with mixed success; it was the only testing ground for his Universal Gravitation. This background for today’s many-body theory is discussed in some detail because all the guiding principles for our understanding can be traced to the earliest developments of astronomy. They are the oldest results of scientific inquiry, and they were the first ones to be confirmed by the great physicist-mathematicians of the 18th century. By a variety of methods, Laplace was able to claim complete agreement of celestial mechanics with the astronomical observations. Lagrange initiated a new trend wherein the mathematical problems of mechanics could all be solved by the same uniform process; canonical transformations eventually won the field. They were used for the first time on a large scale by Delaunay to find the ultimate solution of the lunar problem by perturbing the solution of the two-body Earth-Moon problem. -

Hilbert in Missouri Author(S): David Zitarelli Reviewed Work(S): Source: Mathematics Magazine, Vol

Hilbert in Missouri Author(s): David Zitarelli Reviewed work(s): Source: Mathematics Magazine, Vol. 84, No. 5 (December 2011), pp. 351-364 Published by: Mathematical Association of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.4169/math.mag.84.5.351 . Accessed: 22/01/2012 11:15 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Mathematical Association of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Mathematics Magazine. http://www.jstor.org VOL. 84, NO. 5, DECEMBER 2011 351 Hilbert in Missouri DAVIDZITARELLI Temple University Philadelphia, PA 19122 [email protected] No, David Hilbert never visited Missouri. In fact, he never crossed the Atlantic. Yet doctoral students he produced at Gottingen¨ played important roles in the development of mathematics during the first quarter of the twentieth century in what was then the southwestern part of the United States, particularly in that state. It is well known that Felix Klein exerted a primary influence on the emerging American mathematical research community at the end of the nineteenth century by mentoring students and educating professors in Germany as well as lecturing in the U.S.