The Whipping Man by Matthew Lopez

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

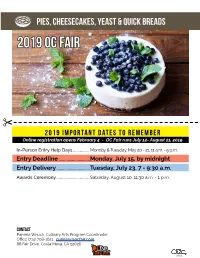

2019 OC Fair

Pies, Cheesecakes, Yeast & Quick Breads 2019 OC Fair 2019 IMPORTANT DATES to remember Online registration opens February 4 - OC Fair runs July 12- August 11, 2019 In-Person Entry Help Days ....................Monday & Tuesday, May 20 - 21, 11 a.m. - 5 p.m. Entry Deadline ............................Monday, July 15, by midnight Entry Delivery ..............................Tuesday, July 23, 7 - 9:30 a.m. Awards Ceremony .......................................Saturday, August 10, 11:30 a.m. - 1 p.m. CONTACT Pamela Wnuck, Culinary Arts Program Coordinator Office (714) 708-1621 [email protected] 88 Fair Drive, Costa Mesa, CA 92626 2019 Pies, Cheesecakes, Yeast & Quick Breads TABLE OF CONTENTS Rules ............................................................................................................................... 1 Eligibility / Entry Limit / Exhibitor Ticket ............................................2 How to Enter / Help with Entering ..........................................................3 Entry Delivery ...........................................................................................................4 Judging .........................................................................................................................5 Awards / Awards Ceremony ........................................................................6 Adult Divisions ...................................................................................................... 7-9 Division 1060 Quick Breads Division 1061 Muffins, Biscuits & Scones -

A Taste of Food in the Civil War

Ellie Schweiker Jolene Onorati Manning school A Taste of Food in the Civil War What’s the way to keep a soldier alive? Strategy? Weaponry? Medicine? Or is it something as basic as food? While many of us take our meals for granted, the Civil War was impacted by the distribution and intake of food. Contrary to popular belief, most Union soldiers had plenty of food. The restrictions experienced by both the Union and Confederate soldiers were the types of food available during the civil war. The army with the soldiers well nourished gained an advantage. Societal norms regarding who prepared the food was also a factor and differed between slave states and free states. Without kitchens with experienced chefs or slaves, soldiers had to cope with the unvaried and insufficient rations they received. As the war began, Union soldiers started to realize the bleak reality of the food they were given. The United States Sanitary Commission, also known as Sanitary, supported and supervised all food allocation in the North. Captain James Sanderson was a notable volunteer who worked for the Sanitary. He noticed the importance of food in a man’s body and how advantageous an ablebodied man can be. After authoring the first cookbook distributed to soldiers, Sanderson helped raise awareness about meals on the battlefield. In Sanderson’s cookbook it was evident he was passionate about soldiers’ nutrition on the battlefield. “Remember that beans, badly boiled, kill more than bullets; and fat is more fatal than powder. In cooking, more than in anything else in this world, always make haste slowly. -

Hardtack – a Cowboy’S Snack

Hardtack – A Cowboy’s Snack It has often been said that “an army marches on its stomach”, showing the importance of staying well supplied and fed. The same could be said of the cowboy and the need for those men riding in the saddle to stay well fed while they made their way up the trail. While at the end of a hard days ride the cowboy would have a chance to fill their stomach when they were able to stop for the night and gather around the chuck wagon for dinner, during the days work there weren’t many chances to stop and take a snack break. If the cowboy wanted to eat something while on their horse working, it required something that was easily carried and could stand up to the stress of the trail. For many a snack, the cowboy turned to a traditional food item that had served many an explorer and soldier alike for a few hundred years…the hardtack cracker. Hardtack: Not quite bread, note quite a biscuit While not sounding very appetizing, hardtack has been found in many a pocket and knapsack throughout history. Having been around since the Crusades, the version of hardtack most commonly found on the American frontier was created in 1801 by Josiah Bent. Bent called his creation a “water cracker” that contained only two ingredients, water and flour. These ingredients would then be mixed into a paste, rolled out, cut into squares, and finally baked. Once the cooking process was over, you’d be left with a dry cracker that would stand up to the elements for a long time, while also not being the most appetizing snack. -

Army Hardtack Recipe

Army Hardtack Recipe Ingredients: •4 cups flour (preferably whole wheat) •4 teaspoons salt •Water (about 2 cups) Preheat oven to 375 degrees. Mix the flour and salt together in a bowl. Add just enough water (less than two cups, so that the mixture will stick together, producing a dough that won’t stick to hands. Mix the dough by hand. Roll the dough out, shaping it roughly into a rectangle. Cut the dough into squares about 3 x 3 inches and ½ inch thick. After cutting the squares, press a pattern of four rows of four holes into each square, using a nail, or other such object. Do not punch all the way through the dough. It should resemble a modern saltine cracker. Turn the square over and do the same to the other side. Place the squares on an ungreased cookie sheet in the oven and bake for 30 minutes. Turn each piece over and bake for another 30 minutes. The crackers should be slightly brown on both sides. Makes about 10 squares. This legendary cracker, consisting of flour, water, and salt, was the main staple of the soldier’s diet. If kept dry, it could be preserved almost indefinitely. Before a campaign, troops were typically issued three day’s worth of rations, including thirty pieces of hardtack. Hardtack was sometimes jokingly referred to as “tooth dullers” or “sheet iron”. The preferred way to prepare hardtack was to soften them in water, and then fry them in bacon grease. However, on the march, soldiers ate them “raw” with a piece of salt pork, bacon, or some sugar. -

Congressional -Record- House

l912 . CONGRESSIONAL -RECORD- HOUSE. '8451 hi House bill 24023, relative to five-year tenure of office for Greailer New Y,ork, against passage of bills restricting immigra Go-v.ernment -employees; to the Committee on Appropda tion; to the :Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. · tions. Also, imemorial of United Garment Workers of America, favor By Mr. BARNHART: Memorial of St. Urban Society, No. , ing passage of the seamen's :om No. 22673, :celative to safety :fo--r 399, of Otis, Ind., against passage of bills restricting 'immigra crew m11d passengers on vessels ; to the Committee on the Mer tion; io the Committee on Immigration and Naturaliza chant l\larine and Fisheries. tion. By Mr. REILLY : Memorial of Trenton Chamber of Com By Mr. BROWN: Papers to accompany a bill for the relief merce, of Trenton, N. J., against passage of Senate bil1 5458. of the heirs of Bryson Hamilton; to the Committee on War relative to placing of bridge by Pennsylvania Railroad Co. 01er Claims. the Delaware lliver -near Trenton; to the Committee on Inter Also, papers to accompany bill for the relief of the heirs of state and 'Foreign Cammerce. Alexander Stolmaker; to the Committee on War Claims. Also, petition of citizens of Bridgeport, Conn., against passage By Mr. CANNON: Memorial of Polish-American citizens of of the Bmton-Littleto.ri bill relative to celebrating 100 years of Chicago, ID., and Polish National Alliance of the United Stutes peace with England; to the Committee on Industrial Arts and of America, against -pas"'age of bills restricting immigration; to Expositions. -

Rhode Island Ewish Historical Notes

RHODE ISLAND EWISH HISTORICAL NOTES VOLUME 5 NOVEMBER. 1968 NUMBER 2 To-uro Synagogue, Newport, R. 1. The oldest .synagogue building in the United States. Dedicated a National Shrine August 31,1947. Origi- nal wood-en graving by Bernard Brussel-Smith for the National Infor- mation Bureau for Jewish Life. Courtesy of Melvin L. Zurier. RHODE ISLAND JEWISH HISTORICAL VOLUME 5, NUMBER 2 NOVEMBER, 1968 Copyright November, 1968 by the RHODE ISLAND JEWISH HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 209 ANGELL STREET, PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND 02906 RHODE ISLAND JEWISH HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 209 ANGELL STREET, PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND DAVID CHARAK ADELMAN, Founder TABLE OF CONTENTS TOURO SYNAGOGUE Front Cover SOUVENIR PROGRAMS Back Covers MYER BENJAMIN AND HIS DESCENDANTS . 133 By Malcolm H. Stern EARLY JEWS OF EAI.L RIVER, MASSACHUSETTS 145 By Rabbi Malcolm H. Stem THE YEAR 1905 IN RHODE ISLAND .... 147 By Beryl Segal SOME OUTSTANDING JEWISH ATHLETES IN R. I. 153 By Benton H. Rosen LONGFELLOW AND THE JEWISH CEMETERY AT NEWPORT By Rev. J. K. Packard, S.J. 168 TEMPLE BETH-EL SEEKS A RABBI .... 175 AHAVATH SHALOM IN WEST WARWICK . 178 By Paul IV. Slreicker FOURTEENTH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE ASSOCIATION . 183 NECROLOGY 185 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS OF THE ASSOCIATION BERNARD SEGAL President JEROME B. SPUNT Vice President MRS. SEEBERT J. GOLDOWSKY .... Secretary MRS LOUIS I. SWEET Treasurer MEMBERS-AT-LARGE OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE RABBI WILLIAM G. BRAUDE WILLIAM L. ROBIN SEEBERT J. GOLDOWSKY, M.D. ERWIN STRASMICH SIDNEY GOLDSTEIN LOUIS I. SWEET MRS. CHARLES POTTER MELVIN L. ZURIF.R SEEBERT JAY GOLDOWSKY, M.D., Editor MISS DOROTHY M. -

Scandinavian Ideas for a South Dakota Christmas Leslie Smith

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Extension Circulars SDSU Extension 9-1949 Scandinavian Ideas for a South Dakota Christmas Leslie Smith Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/extension_circ Recommended Citation Smith, Leslie, "Scandinavian Ideas for a South Dakota Christmas" (1949). Extension Circulars. Paper 425. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/extension_circ/425 This Circular is brought to you for free and open access by the SDSU Extension at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Extension Circulars by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Extension Circular 4 5 3 September 1949 , Scandina'>'ian Ideas for a South Dakota Christmas EXTENSION SERVICE SOUTH DAKOTA STATE COLLEGE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE COOPERATING / Scandinac-vian Ide as Ior a South Dakota Christmas LESLIE SMITH As members of Home Extension Clubs, it is entirely fitting that we extend our policy of "Harmony Around the World" to in clude an appreciation and use of the designs and crafts of other people of other lands. It is hoped that this booklet which presents Scandinavian ideas may be the first of a series of Christmas gift circulars based on that appreciation. It is planned that Christmas gift circulars of coming years will tell of Christmas customs of German, Eastern Europe, English, Irish, French and other peoples who make up our South Dakota ancestry. Wlii.at is Christmas like in the Scandinavian countries? In your In FINLAND, observance starts at five o'clock the day before group you may find many of Scandinavian descent, or those who have Christmas. -

Hardtack Pilot Crackers

Hardtack Pilot Crackers The traditional staple of early missionaries traveling by ship to new lands went by a variety of names— oyster crackers, pilot biscuits, pilot crackers, saloon pilots, ship bread, ship biscuit, sea bread, hardtack, and hard bread. The bakers of the time made biscuits as hard as possible, as the biscuits would soften and become more palatable with time due to exposure to humidity and other weather elements. Because it is hard and dry, hardtack (when properly stored and transported) will survive rough handling and temperature extremes. To soften, hardtack was often dunked in tea, coffee, or some other liquid, or cooked into a skillet meal. Because it was baked hard, it would stay intact for years if kept dry. For long voyages, hardtack was baked four times, rather than the more common two, and prepared six months before sailing. CAL/SERV: 28 YIELDS: 4 DOZEN PREP TIME: 15MINS COOK TIME: 30MINS TOTAL TIME: 45MINS INGREDIENTS 2 c. all-purpose flour plus more for rolling out the crackers 1 1/2 tsp. brown sugar 1 1/2 tsp. salt 3/4 c. milk 2 tbsp. unsalted butter DIRECTIONS Preheat the oven to 400 degrees. Line a baking sheet with parchment. Combine the flour, brown sugar, and salt in a medium bowl and mix. Make a well in the center and add the milk and butter. Stir with a fork until a dough forms; turn out on a lightly floured work surface. Roll out to a 1/2- to 3/4-inch thickness and cut into bite-size squares or pieces. -

Southern Jewish History

SOUTHERN JEWISH HISTORY Journal of the Southern Jewish Historical Society Mark K. Bauman, Editor Rachel Heimovics Braun, Managing Editor Scott M. Langston, Primary Sources Section Editor Stephen J. Whitfield, Book Review Editor Phyllis Leffler, Exhibit Review Editor Dina Pinsky, Website Review Editor 2 0 1 2 Volume 15 Southern Jewish History Editorial Board Dianne Ashton Adam Mendelsohn Ronald Bayor Dan Puckett Hasia Diner David Patterson Kirsten Fermalicht Jonathan Sarna Alan Kraut Lee Shai Weissbach Stephen J. Whitfield Southern Jewish History is a publication of the Southern Jewish Historical Society available by subscription and a benefit of membership in the Society. The opinions and statements expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the journal or of the Southern Jewish Historical Society. Southern Jewish Historical Society OFFICERS: Stuart Rockoff, President; Dale Rosengarten, President Elect; Phyllis Leffler, Secretary; Les Bergen, Treasurer; Jean Roseman, Corresponding Secretary; Bernard Wax, Board Member Emeritus; Leonard Rogoff, Immediate Past President. BOARD OF TRUSTEES: Rachel Bergstein, P. Irving Bloom, Maryann Friedman, Gil Halpern, Allen Krause (z’l), May Lynn Mans- bach, Beth Orlansky, Dan Puckett, Ellen M. Umansky, Lee Shai Weissbach. EX- OFFICIO: Rayman L. Solomon. For authors’ guidelines, queries, and all editorial matters, write to the Edi- tor, Southern Jewish History, 2517 Hartford Dr., Ellenwood, GA 30294; e-mail: [email protected]. For journal subscriptions and advertising, write Rachel Heimovics -

Bisques and Biscuits

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Bisques and Biscuits The word biscuit (from the Middle French bescuit) is derived from the Latin words bis (twice) and coquere, coctus (to cook, cooked). The crustaceans in a French bisque are twice-cooked, as well, first sautéed lightly in their shells, then simmered in a mixture of wine and aromatic ingredients (before being strained), followed by the addition of cream. But in New Orleans, things are different. First of all, the etymology of the word bisque (meaning that cream- ladened Gallic variety) is thought to have originated from Biscay, as in the Bay of Biscay (and not from the same roots as biscuit). On some medieval maps, the Bay of Biscay is designated as El Mar del los Vascos (the Basque Sea). It’s that seafood-rich body of water nestled between Spain and France. Secondly, the classical French culinary traditions of bisque preparation have been superseded by South Louisiana’s dark roux-based soup, brimming with butter, but devoid of the cream as in the European variety. And like a prize in a box of Cracker Jack, our local version has flavorful stuffing encased in each crawfish head (the large red thorax shell), unsuccessfully hiding in our bowl. The famed international writer Lafcadio Hearn, who spent a decade in New Orleans, wrote about stuffing the heads and preparing the bisque “A LA CREOLE” back in 1885 in his popular La Cuisine Créole, a fine collection of culinary recipes from leading New Orleans Creole chefs and housewives. -

Hardtack Recipe to Try out at Home!

History of Hardtack “Tis the song that is uttered in camp by night and day, ‘Tis the wail that is mingled with each snore; ‘Tis the sighing of the soul for spring chickens far away, ‘Oh hard crackers, come again no more!’ ‘Tis the song of the soldier, weary, hungry and faint, Hard crackers, hard crackers, come again no more; Many days have I chewed you and uttered no complaint, Hard crackers, hard cracker, come again no more!” -from a soldier’s poem called “Hard Times” During the Civil War, the food given to soldiers was called rations. These rations usually consisted of salt pork, hardtack, coffee and sugar. Salt pork is made from pig bellies preserved with salt, which prevents it from rotting or molding. Hardtack is a type of hard cracker. The ingredients for making hardtack are flour, salt, water, and a bit of fat. Hardtack became a very important ration because the food could last for years. Soldiers could put the hardtack in their haversack (a bag carried over the shoulder to hold food) and not have to worry that the hardtack would spoil. Sometimes, hardtack became infested with weevils. Weevils were a small bug that enjoyed eating the tough biscuit. Due to the frequent weevil infestations, soldiers called the hardtack “worm castles.” Other names soldiers used for the hardtack were “tooth dullers” and “sheet iron crackers.” Soldiers invented these names because hardtack was so hard it could break the soldier’s teeth! Look on the back of this sheet for a hardtack recipe to try out at home! CIVIL WAR! Information Sheets Go to archives.alabama.gov for more information about Alabama! Hardtack Recipe Ingredients • 6 pinches of salt • 2 c. -

Civil War Traveling Trunk Inventory List “Artifake” Descriptions

CIVIL WAR TRAVELING TRUNK INVENTORY LIST “ARTIFAKE” DESCRIPTIONS What are “artifakes”? The items in this traveling trunk are not really from the 1860s. Those valuable items are kept safely in museums around the world and are called “artifacts.” They are very fragile and people are usually not allowed to touch them. The items we have assembled for you are reproductions of those artifacts. Since they are made today, anyone can touch and examine them! Given that they are not artifacts, we call them “artifakes.” Federal Uniform The “blue suit” issued to Union soldiers was made primarily of wool, which made the uniform very durable. However, this also made it heavy and itchy, which could be unbearable in the spring and summer heat. The four-button “sack coat” was simple to make and issued to thousands of Federal troops. The sky-blue trousers were worn with suspenders. The “kepi” hat was based on a French design and was used extensively throughout the army. Brass numbers and letters were placed on the top of the hat to show the regiment with which the soldier was serving. Confederate Uniform Though commonly associated with the color grey, Southern uniforms also came in shades of tan or brown, which was partially the result of crude attempts to re- move blue dye from captured Northern uniforms. Confederate uniforms were much more ad hoc than Federal uniforms, combining Union pieces, items brought from home, supplies purchased from England, and items made in the Confederacy. The trousers of this uniform are made from “jean cloth”, a combination of wool and cotton fibers that gave clothing the durability of wool with the breathability of cotton.