International Journal for Social Studies Status and Use Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Method and Results of Studying the Geomagnetic Field of Khiva from the Middle of the Sixteenth Century

Izvestiya, Earth Physics Vol. 14, No. 11, 1978 UDe 550.384.32 A Method and Results of Studying the Geomagnetic Field of Khiva from the Middle of the Sixteenth Century K. S. BURAKOVANDI. YEo NACHASOVA The collection gathered at Khiva is represented ;v C = --====::.' by 250 bricks from 32 dated architectural monuments il.'+I; [1]. For the purpose of obtaining information about IlC 1 [ (/xlll.x+/,Il/,)/.' ] the old geomagnetic field in this region, the collection -=- 1M + . was treated by two methods-Tellier's method [2] and C M' •• 1.'+1.' the method of thermal curves. The method of thermal curves, proposed earlier [3], was tested in this study In measuring the magnetization of a sample during on an extensive collection. heating, the sample is mounted in a holder with its y- From the bricks we sawed off cubic samples axis downward, i. e., only the projection of the I mag- xz oriented along the faces of the brick-with an edge of netization vector on the xz plane is measured, and the 24 mm for work according to Tellier's method and with coefficient C shows how many times greater the total an edge of 10 mm for work by the method of thermal moment is than its projection on this plane. curves. Before the measurement the samples were IT there is a secondary magnetization in the sample, carefully washed under a stream of water, in order arising from the time of the laying of the brick in the to remove from the faces and from the pores of the building and, as a rule, not parallel to the primary sample the clay remaining after sawing and polish- magnetization, then the vector in the xz plane will ro- ing the sample. -

Treasures of Uzbekistan

Treasures of Uzbekistan Tashkent – Urgench – Khiva – Bukhara – Shakhresabz – Samarkand – Tashkent from per pax S$1228 Day 01: Tashkent Meeting on arrival assistance and transfer to Hotel Dinner at hotel Overnight Day 02: Tashkent/Urgench – HY 1051 0700/0840 Urgench/Khiva – 30km (40 min) Breakfast at hotel Transfer to Airport for flight to Urgench On arrival proceed to Khiva On arrival transfer to Hotel Full day tour of Khiva visit – Ichan Kala ‘inner city’ historic old city, Kalta Minor Tower, Kunya Ark Fortress, Muhammad Amin-Khan, Ak-Mosque, Necropolis of Pahlavan Mahmud, Minaret and Madrasah of Islam Khodja, Avesta Museum Lunch at local restaurant Later visit Djuma Mosque, Tash-Hauli Khan Palace and Caravan Bazar Dinner at hotel Overnight Day 03: Khiva – Bukhara – 460 km (8-9hr) Breakfast at hotel Morning depart for Bukhara enroute via Kizilkum desert with few stops enroute stop at the sight of Amudarya (Oxus river) Picnic lunch enroute We shall walk up to Lyabikhauz and later stroll through Jewish quarters arrival and transfer to Hotel Dinner at hotel Overnight Day 04: Bukhara Breakfast at hotel Full day sightseeing tour of Bukhara – Visit Lyabikhauz ensemble: Khanaka and Madrassah of Nadirkhon Devanbegi, Kukeldash Madrassah, Mogaki Attari mosque, Complex Poi Kalon and madrassah Aziz Khan and Ulugbek Lunch at local restaurant Afternoon visit Ark Fortress, Balakhauz Mosque, Mausoleum of Ismail Samanid, Chasma Ayub Mausoleum and local bazaar Folk show in madrassah Nadirkhon Devonbegi Dinner at local restaurant Overnight at hotel Day -

Wikivoyage Uzbekistan March 2016 Contents

WikiVoyage Uzbekistan March 2016 Contents 1 Uzbekistan 1 1.1 Regions ................................................ 1 1.2 Cities ................................................. 1 1.3 Other destinations ........................................... 1 1.4 Understand .............................................. 1 1.4.1 History ............................................ 1 1.4.2 Climate ............................................ 2 1.4.3 Geography .......................................... 2 1.4.4 Holidays ............................................ 2 1.5 Get in ................................................. 2 1.5.1 By plane ............................................ 3 1.5.2 By train ............................................ 3 1.5.3 By car ............................................. 3 1.5.4 From Afghanistan ....................................... 3 1.5.5 From Kazakhstan ....................................... 3 1.5.6 From Kyrgyzstan ....................................... 3 1.5.7 From Tajikistan ........................................ 3 1.5.8 By bus ............................................. 4 1.5.9 By boat ............................................ 4 1.6 Get around ............................................... 4 1.6.1 By train ............................................ 4 1.6.2 By shared taxi ......................................... 4 1.6.3 By bus ............................................. 4 1.6.4 Others ............................................. 4 1.6.5 By car ............................................ -

Ministry of Higher and Special Secondary Education Samarkand State Institute of Foreign Languages Chair of Translation Theory and Practice

MINISTRY OF HIGHER AND SPECIAL SECONDARY EDUCATION SAMARKAND STATE INSTITUTE OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES CHAIR OF TRANSLATION THEORY AND PRACTICE TEXTS OF LECTURES on subject Translation of historical monuments of Uzbekistan (O`zbekiston tarixiy obidalari) Samarkand 2014 1 O`zbekiston respublikasi oily va o`rta maxsus ta`lim vazirligi Samarqand davlat chet itllar instituti Tarjima nazariyasi va amaliyoti kafedrasi O`zbekiston tarixiy obidalari fanidan MA`RUZALAR MATNI Ushbu ma`ruzalar matni Samarqand davlat chet tillar instituti ilmiy kengashining 2014 yil 27-avgustdagi 1-son qarori bilan tasdiqlandi hamda ingliz tilida o`tishga ruxsat berildi Tuzuvchi: Tarjima nazariyasi va amaliyoti kafedrasi katta o`qituvchisi, f.f.nN. Yo. Turdieva Taqrizchi: SamDChTI Ingliz tili leksikasi va stilistikasi kafedrasi katta o`qituvchisi, f.f.n. Ro`ziqulov F. Sh. Samarqand 2014 2 Bibliography 1. «UzbеkistоnMilliyentsiklоpеdiyasi» РеспубликаУзбекистан. Энциклопедический справочник. Tоshkеnt 2001. 448 b. 2. MustаqilUzbеkistоn. IndependentUzbekiston.TоshkеntIslоmUnivеrsitеti. 2006. 296 b. 3. UzbеkistоnRеspublikаsiEntsiklоpеdiyasi. Tоshkеnt. 1997. «Qоmuslаr Bоshtахririyati» 4. Sаmаrkаnd аsrlаr chоrrахаsidа. «Samarkand at the crossroads of the centuries» T. 2001 5. Tеmurning mе’mоriy mеrоsi. Puхаchеnkоvа G. А. 1996. Tоshkеnt. 128 b. 6. SuvоnqulоvI. Sаmаrkаnd qаdаmjоlаri. Sаmаrkаnd 2003.88 bеt. 7. Хоdjаеvа S. Sаgdiеvа Z. YusupоvR. ZаrgаrоvаM. “Uzbekistan at the doorstep of the third 8. Millennium.”1998. 350 bеt. 9. Ахmеdоv E. Sаydаminоvа Z. UzbеkistоnRеspublikаsi Republic of Uzbekistan» qisqаchа 10. mа’lumоtnоmа. Tоsh. «Uzbеkistоn», 1998 y 400 b. 11. СаломовГ. ТилваТаржима. - Ташкент, 1966. - 220 б. 12. Саломов Г. Таржима назарияси асослари. - Ташкент, 1970. - 196 б. 13. BеgаliеvN. B. Sаmаrqаnd tоpоnimiyasi. Sаmаrkаnd 2010. SаmDCHTI nаshr mаtbаа mаrkаzi. 128 bеt. 14. www.goldenpages.uz/en/search/%FType.. 15. -

ARAL: the History of Dying Sea

International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea Executive Committee ARAL: the history of dying sea Dushanbe - 2003 U. ASHIRBEKOV, I. ZONN To 10-th anniversary of IFAS and Dushanbe Iternational Forum of fresh water ARAL: THE HISTORY OF DYING SEA Dushanbe - 2003 ÁÁÊ 26.3+26.82+28.081+2689(2) À - 98 Ashirbekov U.A., Zonn I.S. Aral: The History of Dying Sea. Dushanbe, 2003.-86 ñ. This book gives a brief description of the Aral sea till 1960 when the sea started dying out. For the first time it presents the chronology of studying, development and attempts of conservation and reha-bilitation of the Aral sea. Shown is the participation of the world society in cooperation related to envi-ronmental catastrophe. © Ashirbekov U.A., Zonn I.S. It is issued by the decision of IFAS Executive Committee. Under the general edition of Aslov S.M. - Chairman of IFAS Executive Committee Composer: Gaybullaev H.G. Editor: Jamshedov P. The edition is carried out by the financial support of the «Natural Resource Management» Project (NRMP) and the USA Agency on International Development (USAID) «Who does not have past, that does not have future» Popular wisdom INTRODUCTION For the last decades the problem of Aral doesn't come off the pages of mass media. New works appear refreshing new aspects of "life" of drying sea, it's actively discussed on national and international levels. Ten years ago five new independent states of central Asia - Kazakh Republic, Kyrgyz Republic, Republic of Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Republic of Uzbekistan united its efforts for creation of Interstate Coordination Water Commission. -

Of Central Asia 17Sept – 06Oct 2017 (Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan & Kazakhstan)

17Sept – 06Oct 2017 The 4 ‘stans’ of Central Asia (Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan & Kazakhstan) If you’re looking for something off-path in all ways literal and figurative, Central Asia makes a good travel candidate. Filled with incredible mountain landscapes, deserts, Silk Road cities, friendly people and quirky experiences of the Soviet hangover variety, Central Asia is hard to beat when it comes to raw, discover-the-world potential. To this day, it remains one of travellers’ favourites and most fulfilling travel experiences of one of the world’s greatest road trips. This is Central Asia. The ‘Stans’. Never well understood, but absolutely worth an attempt to understand. Come, embark on this journey of discovering the 4 stunning ‘stans’ of Central Asia with us this 17Sept to 06Oct 2017. 1 Flights Schedule: Air Astana KC 17SEP KUL TSE KC 936/991 1055 2030 ( for those who opt for pre-trip extension to Astana ) 19SEP KUL ALA KC 936 1055 1655 05OCT TASALA KC 128 1420 1650 05OCT ALAKUL KC 935 2330 0940 # 06Oct Itinerary 17SEP DAY 01 KUALA LUMPUR – ASTANA @ 2030 ( pre-trip extension ) Arrive Astana airport @ 2030. Meet and greet and transfer to Hotel to check in. Welcome to Astana, capital city of Kazakhstan, one of the strangest capital cities on earth. The flashy buildings of Astana rise up implausibly from the flat plains of oil-rich Kazakhstan to form a city stuck between a Soviet past and an aspirational present. Overnite in Astana 18SEP DAY 02 ASTANA (B/L/D) ( pre-trip extension ) After breakfast, we shall start our sightseeing in this capital of Kazakhstan. -

Mb Travel Tour 212-571-2831 855-326-2840

MB TRAVEL TOUR 212-571-2831 855-326-2840 www.mbtraveltour.com 2019 10 Days/9 Nights TREASURES OF UZBEKISTAN Tashkent – Urgench – Khiva – Bukhara – Shakhresabz – Samarkand – Tashkent Day 01: Arrive Tashkent Meeting On Arrival Assistance And Transfer To Hotel Overnight Day 02: Tashkent/Urgench – Afternoon Or Evening Urgench/Khiva – 30km (40 Min) Breakfast At Hotel Morning Sightseeing Of Tashkent – Visit The Architectural Complex Khazret-Imam Incl. Necropolis Of Imam Abu Bakr Mahammad Al-Kaffal Shashi (15th C.), See Barak-Khan Madrasah, Tillya Sheikh Madrasah, Juma Mosque, Kukeldash Madrasah, Chorsu Market, Alisher Navoi Opera & Ballet Theatre (Outside) (1939-47), Amir Temur Square, Palace Of Grand Duke Nikolay Romanov (Outside) (1889-90), The Roman Catholic Church (1913-17) Transfer To Airport For Flight To Urgench On Arrival Proceed To Khiva On Arrival Transfer To Hotel Dinner With Locala Madrassah Overnight Day 03: Khiva Breakfast At Hotel Full Day Tour Of Khiva Visit – Ichan Kala ‘Inner City’ Historic Old City, Kalta Minor Tower, Kunya Ark Fortress, Muhammad Amin-Khan, Ak-Mosque, Necropolis Of Pahlavan Mahmud, Minaret And Madrasah Of Islam Khodja, Avesta Museum Later Visit Djuma Mosque, Tash-Hauli Khan Palace And Caravan Bazar Overnight Day 04: Khiva – Bukhara – 460 Km (8-9hr) Breakfast At Hotel Morning Depart For Bukhara Enroute Via Kizilkum Desert With Few Stops Enroute Stop At The Sight Of Amudarya(Oxus River) We Shall Walk Up To Lyabikhauz And Later Stroll Through Jewish Quarters Arrival And Transfer To Hotel Overnight Day05:Bukhara -

History of Kazakhstan Architecture

МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ И НАУКИ РЕСПУБЛИКИ КАЗАХСТАН МЕЖДУНАРОДНА ОБРАЗОВАТЕЛЬНАЯ КОРПОРАЦИЯ Glaudinova M.B., Glaudinov B., Galimzhanova A.S., Amandykova D.A., Samoilov K.I., Priemets O.N. HISTORY OF KAZAKHSTAN ARCHITECTURE Textbook Алматы, 2019 МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ И НАУКИ РЕСПУБЛИКИ КАЗАХСТАН МЕЖДУНАРОДНА ОБРАЗОВАТЕЛЬНАЯ КОРПОРАЦИЯ Glaudinova M.B., Glaudinov B., Galimzhanova A.S., Amandykova D.A., Samoilov K.I., Priemets O.N. HISTORY OF KAZAKHSTAN ARCHITECTURE Textbook Алматы, 2019 2 УДК 72.01 (574) (075.8) ББК Г 52 Международная образовательная корпорация Казахская головная архитектурно-строительная академия Рецензенты: доктор архитектуры, проф. Абдрасилова Г.С. доктор архитектуры, проф. А.А. Корнилова Г 52 History of Kazakhstan Architecture: Учебное пособие/ М.Б. Глаудинова, Б.Глаудинов, А.С.Галимжанова, Амандыкова Д.А., Самойлов К.И., Приемец О.Н. - КазГАСА.- Алматы, 2019. – 160 с. ISBN 978-601-7891-25-1 Рассмотрены основные этапы развития истории архитектуры Казахстана. Приведены данные о наиболее значительных памятниках, освещены их архитектурно- планировочные, объемно-пространственные, материало-конструкционные особенности, варианты традиционного декоративно-орнаментального убранства. Определены особенности исторического развития архитектуры на территории Казахстана. Дана характеристика развития архитектуры на современном этапе. УДК 72.01 (574) (075.8) © Международная образовательная корпорация, 2019 ISBN 978-601-7891-25-1 © Глаудинова М.Б. и др., 2019 3 CONTENT 1 Introduction 2 Architecture of Kazakhstan of the most ancient period 3 Architecture of Kazakhstan VIII BC – I AD 4 Architecture of Kazakhstan of the Hunnu period and Turkic khaganates (II-VIII AD) 5 Architecture of Kazakhstan of the VII-IX centuries 6 Architecture of the Karakhanid’ period (IX-XII) 7 Architecture of the Mongolian period (the XIII-XIV centuries) 8 Architecture of the Kazakh khanates period (the XV-XVIII centuries) 9 Architecture of Kazakhstan in XIX c. -

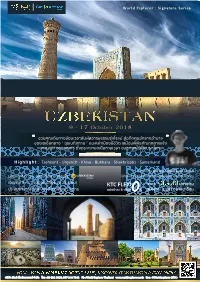

9 - 17 October 2018

World Explorer : Signature Series 9 - 17 October 2018 “ ชวนคุณเดินทางยอนเวลาสัมผัสอารยธรรมรุงโรจน สูอดีตศูนยกลางอํานาจ ” ของเอเชียกลาง “ อุซเบกิสถาน ” ชมเหลาเมืองมีชีวิต เสมือนพิพิธภัณฑกลางแจง คงเสนห ทรงคุณคา ตั้งตระหงานเหนือกาลเวลา จนถูกยกใหเปนมรกโลก Highlight : Tashkent - Urgench - Khiva - Bukhara - Shakhrisabz - Samarkand นำทริปโดย คุณากร วาณิชยวิรุฬห (อ.ตน) นอนหรู 4 ดาว + สบายดวย บินภายใน นักเขียน นักแปล นักเดินทางผูหลงใหลอารยธรรมโบราณ เดินทาง 9 - 17 ตุลาคม 2561 (9 วัน 8 คืน) KTC FLEXI ราคา บาท/ทาน ประสบการณสุดพิเศษรับจำกัดเพียง 16 ทาน แบงชำระ 6 เดือน0% แบงชำระ 11,817 บาท / เดือน บริษัท เวิลด เอ็กซพลอเรอร จำกัด โทร : 02 631 3550, 097 246 7341 Fb : World Explorer Thailand www.worldexplorer.co.th line : @Worldexplorer ( มี@ ) 9 - 17 ตุลาคม 2561 (9 วัน 8 คืน) บินตรงสูอุซเบกิสถานโดย Tashkent Khiva Bukhara Shakhrisabz Samarkand ทองโอเอซิสกลางทะเลทราย เที่ยวเมืองโบราณแหงเสนทางสายไหม“ สำรวจอาณาจักร ของจอมทัพผูสยบเอเชียกลาง ” ชอของ “อซเบกสถาน” อาจพอผานหเรากนมาบาง หลายคนรจกประเทศน ในฐานะประเทศทเกดขนใหม หลงการลมสลายของสหภาพโซเวยต แตถาถามวา ทนอยตรงไหน มอะไรนาเทยวบาง อาจไมใชเรองงายนกทจะตอบคถามน อซเบกสถาน ตงอยใจกลางของเอเชยกลาง เปนประเทศทเรยกวา Double-Landlocked มประวตศาสตรทยาวนานหลายรอยป ครงหนงเคยรงเรองในระดบทเปนศนยกลางอนาจของเอเชยกลาง เคยมผนทเกงกลาเหยมหาญขนาดพชตเอเชยกลาง ปราบสลตานผพชตกองทพครสเตยนในสงครามครเสด ขยายอาณาจกรจากตรกไปจนถงอนเดย ทนเตมไปดวยมรดกโลก มงานสถาปตยกรรมยงใหญ มเมองททงเมองเปนเสมอนพพธภณฑกลางแจง แถมยงมเมองสคญทเปนประตเชอมตะวนออกและตะวนตกบนเสนทางสายไหมอกดวย อซเบกสถาน อาจเปนประเทศทเรายงไมคอยรจก แตนารจกเปนอยางยง World Explorer รวมกบ -

Mb Travel Tour 212-571-2831 855-326-2840

MB TRAVEL TOUR 212-571-2831 855-326-2840 www.mbtraveltour.com 2019 8 Days/7 Nights UZBEKISTAN CLASSIC TOUR TASHKENT – URGENCH – KHIVA – BUKHARA – SHAKHRESABZ – SAMARKAND – TASHKENT Day 01: Tashkent Meeting On Arrival Assistance And Transfer To Hotel Dinner At Local Restaurant Overnight Day 02: Tashkent-Urgench –Khiva – 30km (40 Min) Breakfast At Hotel Transfer To Airport For Flight To Urgench On Arrival Proceed To Khiva On Arrival Transfer To Hotel Full Day Tour Of Khiva Visit – Ichan Kala ‘Inner City’ Historic Old City, Kalta Minor Tower, Kunya Ark Fortress, Muhammad Amin-Khan, Ak-Mosque, Necropolis Of Pahlavan Mahmud, Minaret And Madrasah Of Islam Khodja , Avesta Museum Lunch At Local Restaurant Later Visit Djuma Mosque, Tash-Hauli Khan Palace And Caravan Bazar Dinner At Hotel Overnight Day 03: Khiva – Bukhara – 460 Km (8-9hr) Breakfast At Hotel Morning Depart For Bukhara Enroute Via Kizilkum Desert With Few Stops Enroute Stop At The Sight Of Amudarya(Oxus River) Picnic Lunch Enroute We Shall Walk Upto Lyabikhauz And Later Stroll Through Jewish Quarters Arrival And Transfer To Hotel Dinner At Hotel Overnight Day 04: Bukhara Breakfast At Hotel Full Day Sightseeing Tour Of Bukhara – Visit Lyabikhauz Ensemble: Khanaka And Madrassah Of Nadirkhon Devanbegi, Kukeldash Madrassah, Mogaki Attari Mosque, Complex Poi Kalon And Madrassah Aziz Khan And Ulugbek Lunch At Local Restaurant Afternoon Visit Ark Fortress, Balakhauz Mosque, Mausoleum Of Ismail Samanid, Chasma Ayub Mausoleum And Local Bazaar Folk Show In Madrassah Nadirkhon Devonbegi Dinner -

GEOPOLITICAL and ECONOMIC INTERESTS of the RUSSIAN EMPIRE in the SECOND HALF of the 19Th PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) CENTURY in CENTRAL ASIA

GEOPOLITICAL AND ECONOMIC INTERESTS OF THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE 19th PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) CENTURY IN CENTRAL ASIA GEOPOLITICAL AND ECONOMIC INTERESTS OF THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE 19th CENTURY IN CENTRAL ASIA 1Chinpulat Minasidinovich Kurbanov, 1Sharif Safarovich Shaniyazov, 1Jaloliddin Bakhromovich Nurfayziev, 1Mukhriddin Azimmurod-ugli Sherboboev 1Assistants of the Department "Social Sciences with a course of bioethics" Faculty of International Education, Tashkent State Dental Institute, Tashkent, Uzbekistan Email: [email protected] 1Chinpulat Minasidinovich Kurbanov, 1Sharif Safarovich Shaniyazov, 1Jaloliddin Bakhromovich Nurfayziev, 1Mukhriddin Azimmurod-ugli Sherboboev: Geopolitical And Economic Interests Of The Russian Empire In The Second Half Of The 19th Century In Central Asia-- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(7). ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: Geopolitics, border detachment, industry, capitalist development path, sales market, intermediary role, transit, tariff, economic interests, foreign policy. ABSTRACT In this scientific article, the author examines such issues as Russian industry entered the capitalist path of development, how the importance of Central Asia as a sales market has grown many times. In addition, what a huge intermediary role Central Asia played in the transit of Russian goods to Afghanistan, Iran, India and China. The problems of conquering through the accession and development of new Central Asian markets of the second half of the 19th century became the primary task of the foreign policy of the Russian Empire. The development of new markets led to the gradual blurring of the borders between domestic and foreign markets, which, in turn, contributed to the pulling of many countries into the world market. -

The Marble Bases of Kunya Ark and Tash-Hauli Palaces in Khiva During the 13Th AH/ 19Th AD Century

Journal of the General Union of Arab Archaeologists Volume 4 Issue 2 issue 2 Article 2 2019 The Marble Bases of Kunya Ark and Tash-hauli Palaces in Khiva During the 13th AH/ 19th AD Century Huda Salah El-Deen Omar Lecturer at islamic archaeology department , Faculty of Archaeology- Cairo University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.aaru.edu.jo/jguaa Part of the History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Omar, Huda Salah El-Deen (2019) "The Marble Bases of Kunya Ark and Tash-hauli Palaces in Khiva During the 13th AH/ 19th AD Century," Journal of the General Union of Arab Archaeologists: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.aaru.edu.jo/jguaa/vol4/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Arab Journals Platform. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the General Union of Arab Archaeologists by an authorized editor. The journal is hosted on Digital Commons, an Elsevier platform. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Omar: The Marble Bases of Kunya Ark and Tash-hauli Palaces in Khiva D (JOURNAL OF The General Union OF Arab Archaeologists (5 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ The Marble Bases of Kunya Ark and Tash-hauli Palaces in Khiva During the 13th AH/ 19th AD Century Huda Salah El-Deen Omar Abstract: Khiva is one of the most important cities in Central Asia and it has great geographical, historical, commercial and cultural significance.