Cultural Objects : an Inquiry Into Embedded Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JAY MANGALAMURTI (Aarti to Shri Ganesha)

Aartis 1 JAY MANGALAMURTI (Aarti to Shri Ganesha) Sukha Karta Dukha Harta Varta Vighnachi You are the One who offers happiness and removes sorrows at the time of danger. Nurvi Purvi Prem Krupa Jayachi You offer tender lots of love and blessings Sarvangi Sunder Uti Shendurachi You have red paste on Your body Kanthi Jhalke Mal Mukta Falanchi and wear a pearl necklace. Chorus: Jai Dev., Jai Dev., Jai Mangalamurti Victory to You, most auspicious One! Darshan Matre Mana Kamana Purti Even by Your glance You fulfill the desires in our minds. Jai Dev., Jai Dev. Victory, O God! Ratna Khachita Fara Tuza Gauri Kumara The Goddess Gauri is present by Your side Chandanachi Uti Kumkum Keshara Bedecked with gems and jewellery. Hire Jadita Muguta Shobhato Bara The diamond studded crown on Your head adds to Your gracefulness, Runjhunti Nupure Charni Ghagariya The anklets on Your feet make heavenly music. Lambodar Pitambar Fanivar Bandhana I always have in mind Your long belly, Your pitambar (silk dhoti), Kundalini on Your stomach Saral Sonda Vakratunda Trinayana Your straight trunk, Your innocent face with its three eyes. Das. Ramacha Vat. Pahe Sadana The servant of Shri Rama is waiting for You in this house (body). Sankashti Pavave Nirvani Rakshave Please protect us from calamities and sorrows. O Highest amongst Gods, we bow to You! Survar Vandana Aartis 2 ARATI NIRMALA MATA Chorus: Arati Nirmala Mata ) Aarti to Mother Nirmala > Charni Thevila Me Mata ) (x2) I have surrendered to You Arati Nirmala Mata Aarti to Mother Nirmala Adi Shakti Kundalini Oh Primordial power of the Kundalini who Sarva Vishwachi Janani is the Mother of the Universe Nirguna He Rupa Tuzhe Your form is beyond the Gunas and now Zahli Saguna Tu Ata You have become Saguna (of good qualities). -

![8`Ge F Gvz]D C'= Tc ^` Vezdrez` A]R](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7130/8-ge-f-gvz-d-c-tc-vezdrez-a-r-2377130.webp)

8`Ge F Gvz]D C'= Tc ^` Vezdrez` A]R

/ 0 !"#$ %&'! !"#$" !"#$% &' 1+''1 41 56 $+1 !23 -%#/! 5 1 / 2 (0 7/ ( ( 1 5 81 4 / 5 / ( ( 56 2 3 4 2 &(& )*+ , -'& $$ ( )(*) +)) ,', ,-,' Q estimated value corresponds to 14 per cent of the proposed outlay for Centre under the National Infrastructure Pipeline (43 lakh crore). s India is engaged in a big New Delhi: Amid deepening The end objective of this Arescue operation to bring crisis in Afghanistan after the initiative is to enable “infra- out its citizens from strife- Taliban took over the war- structure creation through torn Afghanistan, External torn nation, a large number of monetisation” wherein the Affairs Minister S Jaishankar Afghan refugees in India vocif- public and private sector col- will brief Parliamentary lead- erously protested in front of the laborate, each excelling in their ers of various political parties UNHCR office here on core areas of competence, so as on August 26 about the situ- Monday demanding release of to deliver socio-economic ation there. “support letters” from the UN inance Minister Nirmala growth and quality of life to the This forthcoming all- agency to migrate to other FSitharaman on Monday country’s citizens, she added. party interaction comes at $$ $# countries for better opportu- announced an ambitious 6 In the railways sector, as the direction of Prime *" + #( $ % nities. lakh crore National many as 400 railway stations, Minister Narendra Modi, Monetisation Pipeline (NMP) 90 passenger trains, 741-km Parliamentary Affairs Minister of Parliamentary Sources said first ever brief- aimed at unlocking value in Konkan Railways and 15 rail- Minister Pralhad Joshi said Affairs @JoshiPralhad will be ing of this sort is expected to infrastructure assets across way stadiums and colonies are here on Monday. -

Puranas, Lord Jagannath Was Originally Worshipped As Lord Neela Madhaba, by a Savar Tribal Chief, Named Viswavasu

Newsletter Archives www.dollsofindia.com Char Dham - The Four Most Sacred Pilgrimages of Hindus Copyright © 2016, DollsofIndia Char Dham, literally meaning, four pilgrimage sites, are the temples that are among the most highly venerated Hindu Vaishnavite temples in India. These four places of pilgrimage, which were defined by Adi Shankaracharya, include Puri, Rameswaram, Dwarka and Badrinath. Hindus consider it a great fortune to visit the Char Dham during their lifetime. Till the mid- 20th century, other pilgrimage sites in the Indian State of Uttarakhand, namely, Yamunotri, Gangotri and Kedarnath, were known as Chota Char Dham. But not, these sites have also been referred to as the Char Dham. The Creation of the Char Dham The Four Shankaracharya Peeths at the Char Dham school of Hinduism gave rise to at least four Hindu Mathas or monastic establishments. The great saint/seer organized the monks under the four Mathas, headquartered at Jagannatha Puri (in the East), Sringeri Sharada Peetham (in the South), Dwarka (in the West) and Badrikashrama (in the North). Each one of these Peethams was headed by one of the shishyas, who oversaw the entire functioning of his respective Matha. Let us now look at each of these temples in detail: The Puri Jagannath Temple Puri Dham Temple Puri is located in the Eastern side of India, in the state of Odisha. Puri is one of the most ancient cities in the East and is situated along the coast of the Bay of Bengal. Puri is the site of the Govardhana Matha. The main temple is about 1000 years old and was constructed in the 12th century by Raja Anantavarman Chodaganga Deva. -

Construction of Rath Yatra Chariots Allowed

Construction of Rath Yatra Chariots Allowed drishtiias.com/printpdf/construction-of-rath-yatra-chariots-allowed Why in News The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) has allowed the construction of chariots for the annual Rath Yatra at Jagannath Puri in Odisha. It has also said that the complete segregation of the construction site should be ensured and social-distancing norms be followed. The Rath Yatra is expected to be held on 23rd June 2020. Jagannath Rath Yatra Ratha Jatra, also called as Chariot Festival, is a Hindu festival associated with Lord Jagannath held at Puri, Odisha. The festival is celebrated on the 2nd day of Shukla Paksha of Ashadh, the third month, according to the traditional Oriya calendar. It is a 9 day-long event and marks the return of Lord Krishna to Vrindavan with his brother Balabhadra and sister Subhadra to Gundicha Temple via Mausi Maa Temple (maternal aunt's home) near Saradha Bali, Puri. During the festival, the three holy chariots carrying idols of Lord Jagannath, his brother Balaram (Balabhadra) and sister Subhadra are pulled by thousands of devotees from India and abroad. Jagannath Temple The temple is believed to be constructed in the 12th century by King Anatavarman Chodaganga Deva of the Eastern Ganga Dynasty. Jagannath Puri temple is called ‘Yamanika Tirtha’ where, according to the Hindu beliefs, the power of ‘Yama’, the god of death has been nullified in Puri due to the presence of Lord Jagannath. This temple was called the “White Pagoda” and is a part of Char Dham pilgrimages (Badrinath, Dwaraka, Puri, Rameswaram). 1/2 There are four gates to the temple- Eastern ‘Singhdwara’ which is the main gate with two crouching lions, Southern ‘Ashwadwara’, Western 'Vyaghra Dwara and Northern ‘Hastidwara’. -

Fading Festivals of Odisha

FADING FESTIVALS OF ODISHA Colonel JC Mahanti (Retired) FADING FESTIVALS OF ODISHA (A peep into the religious practices in Odisha) Colonel JC Mahanti (Retired) To my parents late Brajasundar Mahanti (formerly of Indian Administrative Service) and late Shanti Devi. CONTENTS Preface xiii Sankrantis, Amabasyas, Purnima and Ekadashis 1 Mythology about Surya and Chandra 2 Surya 2 Chandra 3 Surya paraga and Chandra grahana 5 Sankrantis 7 Upabasha 9 Mesha sankranti 10 Mithuna sankranti 11 Karkata sankranti 12 Kanya sankranti 12 Tula sankranti 12 Dhanu sankranti 13 Makara sankranti 14 Amabasyas, Purnimas and Ekadashis 17 Amabasyas 18 Jyestha (Savitri) amabasya 18 Srabana (Chitalagi) amabasya 18 Bhadrava (Satpuri) amabasya 19 Aswina (Mahalaya) amabasya 19 Kartika (Dipavali) amabasya 20 Pousa (Bakula) amabasya 20 Purnimas 21 Baisakha, (Budha or Chandana) purnima 21 Jyestha (Snanna) purnima 21 Ashada (Vyasa) purnima 22 Sravana (Gamha or Rakhi) purnima 22 Bhadrava purnima 23 Aswina (Kumara) purnima 24 Kartika (Rasha) purnima 24 vii Fading Festivals of Odisha Margasira (Pandu) purnima 26 Pausa purnima 26 Magha (Agira) purnima 26 Phalguna (Dolo) purnima 26 Chaitra purnima 27 Ekadashis 27 Varathani ekadashi 29 Mohini ekadashi 30 Jalakrida ekadashi 30 Nirjala ekadashi 30 Khalilagi ekadashi 31 Harisayana (Padma) ekadashi 31 Kamana ekadashi 32 Putrada ekadashi 32 Aja ekadashi 33 Vishnu parswa paribartana ekadashi 33 Indira ekadashi 34 Papankusha ekadashi 34 Rama ekadashi 34 Deba uhapana ekadashi 35 Utparna ekadashi 36 Vaikuntha ekadashi 36 Safala ekadashi -

Jagannath Temple - Overview Jagannath Temple Was Built in the City of Puri by King Chodaganhadeva in 12Th Century

COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – MONUMENTS 0 7830294949 Jagannath Temple - Overview Jagannath Temple was built in the city of Puri by King Chodaganhadeva in 12th century. He also built the Sun temple of Konark. His grandson Ananga Bhimadeva completed the construction of the temple in 12th century. There are three main deities in the temple who are put into the temple cars during the festival of Rath Yatra and these deities are Lord Jagannath, Balabhadra, and Subhadra. Puri Puri is a city in Odisha state that is popular for Jagannath Temple. That’s the reason people come here as it is one of the temples for pilgrimage during Char Dham Yatra. Jagannath Temple was plundered by Hindu and Muslim rulers 18 times to rob the treasure of the temple. Besides the Jagannath temple, many other temples are also there which the tourists can visit. THANKS FOR READING – VISIT OUR WEBSITE www.educatererindia.com COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – MONUMENTS 0 7830294949 Visiting Hours The temple is opened for the public from 5:00am in the morning to 12:00 midnight. The temple is closed from 1:00pm to 4:00pm as a long break is given. There are many rituals performed in the temple which have different timings. Tickets There is no entry fees and people can visit the temple any time during the visiting hours. As many festivals are celebrated here, people can participate in them without paying any fees. Best time to visit Jagannath Temple can be visited during the period of November to February as the climate is very pleasant. -

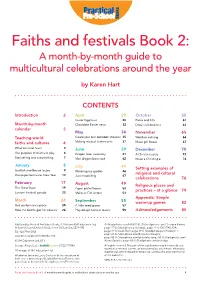

Faiths and Festivals Book 2: a Month-By-Month Guide to Multicultural Celebrations Around the Year

Books Faiths and festivals Book 2: A month-by-month guide to multicultural celebrations around the year by Karen Hart CONTENTS Introduction 2 April 29 October 60 EasterEgghunt 30 RamaandSita 61 Month-by-month ChocolateEasternests 32 Diwalicelebrations 62 calendar 3 May 34 November 65 Teaching world Createyourownkoinoboristreamer 35 Weatherwalking 66 faiths and cultures 4 Makingmusicalinstruments 37 Makegiftboxes 67 Whatwemustteach 5 June 39 December 70 6 Thepurposeofdramaticplay Dragonboatassembly 41 AChristmasplay 72 Storytellingandstorymaking 7 Minidragonboatrace 42 MakeaChristingle 74 January 8 July 44 Setting examples of Scottishshortbreadrecipe 9 46 Wateringmygarden religious and cultural Groupperformance:NewYear 13 Junkmodelling 47 celebrations 76 February 17 August 49 Religious places and TheGreatRace 19 PaperplateMoons 52 practices – at a glance 79 LanternFestivalparade 20 MakeanEidlantern 53 Appendix: Simple March 24 September 55 warm-up games 82 Holiperformancepiece 25 Alittleseedgrows 57 Howthebeetlegothercolours 26 Playdoughharvestloaves 59 Acknowledgements 85 Published by Practical Pre-School Books, A Division of MA Education Ltd, © iStockphoto.com/HAIBO BI, © iStockphoto.com/Christine Keene; St Jude’s Church, Dulwich Road, Herne Hill, London, SE24 0PB. page 17 © iStockphoto.com/jabaa; page 20 © SXC/TALUDA; Tel: 020 7738 5454 page 34 © Karen Hart; page 39 © iStockphoto.com/flytosky11; page 49 © iStockphoto.com/DistinctiveImages; www.practicalpreschoolbooks.com page 50 © iStockphoto.com/pictafolio; page 53 © iStockphoto.com/ © MA Education Ltd 2013 AtomicSparkle; page 65 © iStockphoto.com/pelvidge. Design: Alison Cutler fonthillcreative 01722 717043 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, All images © MA Education Ltd. mechanical, photocopied or otherwise, without the prior permission All photos taken by Lucie Carlier with the exception of of the publisher. -

Fullest Possible Extent “Last Time During the First Wave, Lockdown Being Implemented in Ministrations Have Been Given Ers

y k y cm SATISFYING STINT RUSSIA WARNS US MAIDEN VICTORY Actor Yami Gautam says her nine years President Putin warns the US of swift Jonny Bairstow helps Sunrisers Hyderabad win in the film industry has been an retaliation if it provokes Russia in any their 1st game in the ongoing edition of IPL against Punjab Kings incredible journey LEISURE | P2 manner INTERNATIONAL | P10 SPORTS | P12 VOLUME 11, ISSUE 22 | www.orissapost.com BHUBANESWAR | THURSDAY, APRIL 22 | 2021 12 PAGES | `4.00 They shut O2 supply, 24 dead PATIENTS WERE UNDERGOING TREATMENT AT A MUNICIPAL HOSPITAL IN NASHIK FOR CORONAVIRUS AGENCIES A SOCKET IN THE OXYGEN MAHARASHTRA ment. As far as oxygen supply is con- TANK BROKE WHICH CAUSED GOVERNMENT ANNOUNCES cerned, the NMC received dura cylin- STUDENTS’ DEMAND FULFILLED Nashik/Mumbai, April 21: Twenty- 150 ders from places where the consump- THE LEAKAGE LEADING TO `5 LAKH RELIEF FOR PATIENTS IN THE HOSPITAL four COVID-19 patients, with at least tion is less. Oxygen will be supplied to THE TRAGEDY FAMILIES OF THE DECEASED 11 of them on ventilator support, suf- WERE ON OXYGEN SUPPORT the patients from these cylinders. focated to death Wednesday when Currently, all others undergoing treat- GOVT CANCELS their oxygen supply stopped suddenly ment are stable,” he said. because of a malfunction in the main Divisional Revenue Commissioner storage at the Dr Zakir Husain Radhakrishna Game said a 13 KL Municipal Hospital in Nashik, officials (kilolitre) oxygen tank was set up on MATRIC EXAMS said. The supply was disrupted due the premises of the hospital. -

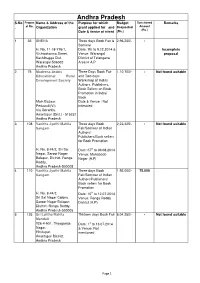

Andhra Pradesh S.No Propos Name & Address of the Purpose for Which Budget Sanctioned Remarks

Andhra Pradesh S.No Propos Name & Address of the Purpose for which Budget Sanctioned Remarks . al No. Organization grant applied for and Requested Amount (Rs.) Date & venue of event (Rs.) 1 35 SNEHA Three days Book Fair & 2,96,250/- - Seminar H. No. 11-18-776/1, Date: 7th to 9.12.2014 & Incomplete Vishwakarma Street, Venue: Warangal proposal Kashibugga Dist. District of Telangana Warangal-506002 Area in A.P Andhra Pradesh 2 75 Madeena Arabic Three Days Book Fair 1,10,700/- - Not found suitable Educational Rural and Two days Development Society Workshop of Indian Authors, Publishers, Book Sellers on Book Promotion in India/ Book Main Bazaar, Date & Venue : Not Pedaoalli(VI) intimated Via Gorantla, Anantapur (Dist.) - 515231 Andhra Pradesh 3 108 Vanitha Jyothi Mahila Three days Book 2,23,425/- - Not found suitable Sangam Fair/Seminar of Indian Authors/ Publishers/Book sellers for Book Promotion H. No. 8-44/2, Sri Sai Date: 07 th to 09.08.2014 Nagar, Saroor Nagar Venue: Mahaboob Balapur, District- Ranga Nagar (A.P) Reddy, Andhra Pradesh-500005 4 110 Vanitha Jyothi Mahila Three days Book 1,92,000/- 75,000 Sangam Fair/Seminar of Indian Authors/Publishers/ Book sellers for Book Promotion H. No. 8-44/2, Date: 10 th to 12.07.2014 Sri Sai Nagar Colony, Venue: Ranga Reddy Saroor Nagar Balapur, District (A.P) District- Ranga Reddy, Andhra Pradesh-500005 5 126 Sri Lalitha Mahila Thirteen days Book Fair 6,04,250/- - Not found suitable Mandali #26-4-901, Thyagaraja Date: 1 st to 13.07.2014 Nagar, & Venue: Not Hindupur, mentioned Anantapur District, -

RESTOUT FINAL.Xlsx

INFRATE Wa Registrat Landmark Full Name Of Father/Husband Adhar ID CH rd Sex Age Phone No. ion No (Place) Vendor Name No. sl Sl.No. No no SV/PURI/1/ Lokanath 1 1 Chudunga Sahi Amit Kumar Jena M 53 8984541357 N/A 1 0007 Behera( पता) SV/PURI/1/ Near Markandeswar Purna Chandra 2 1 Ashok Ku Sahoo M 38 8018014444 N/A 0012 Temple Sahoo( ) 2 पता SV/PURI/1/ Near Markandeswar 3 1 Chandrasekhar Jena Raj Kishor Jena( ) M 30 9090955975 N/A 0011 Temple पता 3 SV/PURI/1/ Markandeswar 5 1 Kuna Nayak Kalia Nayak( ) M 30 7539012033 N/A 4 0004 Temple Back Side पता SV/PURI/1/ 6 1 Markandeswar Sahi Kusuma Dei Rajkisor Jena( ) F 22 N/A N/A 5 0008 पता SV/PURI/1/ Chandamani 7 1 Masani Chhak Maguni Bhoi M 62 N/A N/A 6 0006 Bhoi( पता) SV/PURI/1/ Markandeswar 8 1 Manas Mohanty Bhola Mohanty( ) M 35 N/A N/A 7 0003 Temple Back Side पता SV/PURI/1/ 9 1 Markandeswar Sahi Monarama Behera Purna Prusty( ) F 32 N/A N/A 8 0010 पता SV/PURI/1/ 10 1 Markandeswar Sahi Pradeep Prusty Kalia Nayak( ) F 55 7064066229 N/A 9 0009 प त SV/PURI/1/ Near Markandeswar Gangadhar 12 1 Raj Kishor Jena M 52 9090955975 N/A 0001 Temple Jena( ) 10 पता SV/PURI/1/ Near Markandeswar 14 1 Rinki Patra Ranjan Ku Patra( ) F 25 7537804264 N/A 0013 Street प त 11 Laxmi Bazar Near SV/PURI/2/ Laxmi Dhara 17 2 Jagannath Temple Biranchi Panda M 32 9778325083 N/A 0008 Panda( ) 12 Utara Dwar पता Laxmi Bazar Near SV/PURI/2/ 19 2 Jagannath Temple Damodara Sahoo Hadu Sahoo( ) M 58 N/A N/A 0012 पता 13 Utara Dwar Laxmi Bazar Near SV/PURI/2/ Dinabandhu 24 2 Jagannath Temple Prakash Ku Lenka M 25 9583839333 N/A 0018 -

Car Festival

ODISHA REFERENCE ANNUAL - 2014 CAR FESTIVAL ‘RATHA JATRA’ or the ‘Car Festival’ is the most important festival of Lord Jagannath. This colourful festival, which draws millions of devotees from various parts of the country as well as from abroad to Puri, is held in June-July every year. Lord Jagannath, which literally means the Lord of the Universe, comes out of His sanctum sanctorum to give audience or Darshan to all devotees belonging to all sects and communities among the Hindus. Those who take part in the Car Festival earn their passage to the Heaven. ‘Snana Purnima’ marks the beginning of this festival. On this day the three deities–Lord Jagannath, Lord Balabhadra and Devi Subhadra take prolonged bath on an open platform known as ‘Snana Bedi’. Then they retire for 15 days popularly called the period of ‘Anabasara’ and remain in isolation ; the Gods come out of the temple in a colourful procession to board their respective Chariots and thereafter begin the Journey known as ‘Ratha Jatra’. Reference to Car Festival is available in various scriptures like those of Buddhists, Jains and Hindus. However, the present concept of Lord Jagannath is most popular. According to the prevailing concept, Lord Jagannath was originally worshipped by savaras, a Scheduled Tribe of Orissa. Car Festival symbolizes the Lord’s desire to come out of the temple for a brief period to give audience to the ‘Patitas’ (i.e., the lowest of the low) and redeem them. The chariots of Lord Jagannath and His brother Balabhadra and sister Subhadra are drawn by thousands of devotees in three gorgeously decorated chariots from the main gate of the temple to Gundicha Mandir near about 3 Kms. -

Annual Report 2014-2015 (English)

ANNUAL REPORT 2014-15 NATIONAL BOOK TRUST, INDIA 2015 (Saka 1937) Published by the Director, National Book Trust, India Nehru Bhawan, 5 Institutional Area, Phase-II, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi- 110 070 Typesetted & Printed by Deft Creations, 1740/6, Shersingh Bazar, Kotla Mubarakpur, New Delhi 110003 CONTENTS Introduction 5 Publishing 10 New Delhi World Book Fair, 2015 18 Book Fairs 34 Promotion of Indian Books Abroad 38 Literary Activities During 2014 - 15 46 57th Foundation Day Celebrations 49 National Book Week 51 Activities in North East 53 Activities in Jammu and Kashmir 57 Activities by National Centre for Children’s Literature 59 Regionwise List of Participation of the Trust in Various Book Fairs/Exhibitions 64 Sales & Marketing 70 National Book Trust, India Financial Assistance Programme (Nbt FAP) 72 Promotion and Sale of Books Through Mobile Exhibition Vans 74 Training Course in Book Publishing 76 Shiksha Shivir 78 List of Grantees Under Grant-In-Aid Scheme for Book Related Activities 81 Officers of the Trust 89 Members of the Executive Committee 91 Members of the Board of Trustees 92 Titles Published During 2014-15 94 Audited Annual Account 141 INTRODUCTION The National Book Trust, India is an autonomous body established by the Government of India in the year 1957 for the promotion of books and developing reading habit in the country. Publishing Publishing forms a major activity of the Trust. It publishes a wide variety of reasonably priced quality books ranging from works of fiction to books on medical sciences and cutting edge technology for all segments of the society and for all age groups, including a wide variety of illustrated books for children.