Bulletin 162 Phoyo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart in the Jungle

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Avatars of the Work Ethic: The Figure of the Classical Musician in Discourses of Work Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/71g9n4gd Author Sim, Yi Hong Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Avatars of the Work Ethic: The Figure of the Classical Musician in Discourses of Work A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Yi Hong Sim Committee in charge: Professor Robert Horwitz, Chair Professor Akosua Boatema Boateng Professor Amy Cimini Professor Nancy Guy Professor Daniel Hallin Professor Stefan Tanaka 2019 The Dissertation of Yi Hong Sim is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California San Diego 2019 iii EPIGRAPH On one side, the artist is kept to the level of the workingman, of the animal, of the creature whose sole affair is to get something to eat and somewhere to sleep. This is through necessity. On the other side, he is exalted to the height of beings who have no concern but with the excellence of their work, which they were born and divinely authorized to do. William Dean Howells, A Traveler from Altruria (1894) iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ...................................................................................................................... -

Furman Alumni News Furman University

Furman Magazine Volume 49 Article 25 Issue 4 Winter 2007 1-1-2007 Furman Alumni News Furman University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarexchange.furman.edu/furman-magazine Recommended Citation University, Furman (2007) "Furman Alumni News," Furman Magazine: Vol. 49 : Iss. 4 , Article 25. Available at: https://scholarexchange.furman.edu/furman-magazine/vol49/iss4/25 This Regular Feature is made available online by Journals, part of the Furman University Scholar Exchange (FUSE). It has been accepted for inclusion in Furman Magazine by an authorized FUSE administrator. For terms of use, please refer to the FUSE Institutional Repository Guidelines. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALUMNI IN POLITICAL SPOTLIGHT BRING ATTENTION TO ALMA MATER . .................. ........... .. It's always a point of pride when I see had served in Congress from 1998 to alumni making their marks. From music 2004, when he lost in a bid for a fourth to medicine to teaching to literature term to Republican Mike Sodrel. The whatever the profession, members of the 2006 election marked their third close Furman fa mily consistently help to better race - Hill had edged Sodrel in 2002 - the world. In doing so, they bring great and this time the Furman alumnus rode honor to alma mater. the wave of disenchantment with In recent months, three alumni who Republican leadership back into office. are no strangers to readers of university Hill is part of the "Blue Dog publications have earned extensive Mike McConnell Mark Sanford Baron Hill Coalition," a group of conservative-to attention in the political arena. moderate Democrats who, according The new year had barely begun before the Sanford, who was kind enough to invite the to their Web site, strive "to bridge the gap between announcement came that President Bush had named Furman Singers to perform at both of his inaugurations, ideological extremes." Perhaps he and his colleagues retired Vice Adm. -

Talking Book Topics July-August 2017

Talking Book Topics July–August 2017 Volume 83, Number 4 About Talking Book Topics Talking Book Topics is published bimonthly in audio, large-print, and online formats and distributed at no cost to participants in the Library of Congress reading program for people who are blind or have a physical disability. An abridged version is distributed in braille. This periodical lists digital talking books and magazines available through a network of cooperating libraries and carries news of developments and activities in services to people who are blind, visually impaired, or cannot read standard print material because of an organic physical disability. The annotated list in this issue is limited to titles recently added to the national collection, which contains thousands of fiction and nonfiction titles, including bestsellers, classics, biographies, romance novels, mysteries, and how-to guides. Some books in Spanish are also available. To explore the wide range of books in the national collection, visit the NLS Union Catalog online at www.loc.gov/nls or contact your local cooperating library. Talking Book Topics is also available in large print from your local cooperating library and in downloadable audio files on the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site at https://nlsbard.loc.gov. An abridged version is available to subscribers of Braille Book Review. Library of Congress, Washington 2017 Catalog Card Number 60-46157 ISSN 0039-9183 About BARD Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics are available to eligible readers for download. To use BARD, contact your cooperating library or visit https://nlsbard.loc.gov for more information. -

Virtual BACH FESTIVAL OREGON BACH FESTIVAL 2021

LISTENING GUIDE June 25- July 11, 2021 OREGONVirtual BACH FESTIVAL OREGON BACH FESTIVAL 2021 Welcome to the 2021 Oregon Bach Festival In times of uncertainty, music is a constant in our lives. Music offers catharsis. It keeps us entertained, conjures memories, and expresses our deepest emotions.Music is everywhere. And during this divisive and tumultuous moment, we’re grateful that music is a powerful and relentless force that universally connects us. As we continue to fight a world-wide pandemic together, OBF invites you to join the global community of music lovers who will listen and watch the 2021 virtual Festival from the comfort and safety of their own spaces.All events are presented free and on-demand. A new concert is posted every day at noon and, unless otherwise noted, will remain available throughout the Festival. Whether you’re watching at home alone or you’re gathered with a socially distanced group of friends for a watch party, we hope you enjoy the 2021 slate of brilliant works. We’ll see you for a return to live music in 2022! June 25 Bach Listening Room with Matt Haimovitz June 25 Dunedin Consort: Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos 5 & 6 June 26 Paul Jacobs: Handel & Bach Recital June 27 To the Distant Beloved with Tyler Duncan June 28 Visions of the Future Part 1: Miguel Harth-Bedoya (48 hours only) June 29 Dunedin Consort: Lagrime Mie June 30 Visions of the Future Part 2: Eric Jacobsen (48 hours only) July 1 Emerson String Quartet July 2 Visions of the Future Part 3: Julian Wachner (48 hours only) July 3 Lara Downes presents -

HENRY and LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL of MUSIC SPRING 2017 Fanfare

HENRY AND LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC SPRING 2017 fanfare 124488.indd 1 4/19/17 5:39 PM first chair A MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN One sign of a school’s stature is the recognition received by its students and faculty. By that measure, in recent months the eminence of the Bienen School of Music has been repeatedly reaffirmed. For the first time in the history of the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, this spring one of the contestants will be a Northwestern student. EunAe Lee, a doctoral student of James Giles, is one of only 30 pianists chosen from among 290 applicants worldwide for the prestigious competition. The 15th Van Cliburn takes place in May in Ft. Worth, Texas. Also in May, two cello students of Hans Jørgen Jensen will compete in the inaugural Queen Elisabeth Cello Competition in Brussels. Senior Brannon Cho and master’s student Sihao He are among the 70 elite cellists chosen to participate. Xuesha Hu, a master’s piano student of Alan Chow, won first prize in the eighth Bösendorfer and Yamaha USASU Inter national Piano Competition. In addition to receiving a $15,000 cash prize, Hu will perform with the Phoenix Symphony and will be presented in recital in New York City’s Merkin Concert Hall. Jason Rosenholtz-Witt, a doctoral candidate in musicology, was awarded a 2017 Northwestern Presidential Fellowship. Administered by the Graduate School, it is the University’s most prestigious fellowship for graduate students. Daniel Dehaan, a music composition doctoral student, has been named a 2016–17 Field Fellow by the University of Chicago. -

Fox Life Presenta Segunda Temporada De Mozart in the Jungle En Exclusiva En Claro Video

FOX LIFE PRESENTA SEGUNDA TEMPORADA DE MOZART IN THE JUNGLE EN EXCLUSIVA EN CLARO VIDEO La nueva temporada de la serie ganadora de los Golden Globes 2016 como “Mejor Serie de Televisión de Comedia” ya se encuentra a disposición de los suscriptores de su servicio Claro video Los usuarios disfrutarán de un nuevo episodio cada martes Lima, enero de 2016.- El mundo de las grandes orquestas sinfónicas parece ser uno de extrema educación, sobriedad y armonía, pero, ¿qué ocurre cuando cae el telón después de un concierto? Los suscriptores de Claro video podrán descubrirlo con el estreno de la segunda temporada de la miniserie Mozart In The Jungle que Fox Life presenta de forma exclusiva a través de la pantalla de Claro video antes de su estreno oficial. Además, los usuarios podrán disfrutar cada martes de un nuevo episodio de la producción ganadora de los Golden Globes 2016 como “Mejor Serie de Televisión de Comedia”, y con la que el actor mexicano Gael García Bernal logró el premio a “Mejor Actor en una Serie de Comedia” en los Golden Globe Award. Mozart In The Jungle cuenta la historia de Rodrigo (García Bernal), un talentoso y excéntrico director de orquesta que es contratado para hacerse cargo de la Orquesta Sinfónica de Nueva York. Con un particular espíritu e ideas revolucionarias, la llegada de Rodrigo a la Orquesta implicará grandes cambios que muchos de los miembros actuales rechazarán con recelo. Sin embargo, para Haley (Lola Kirke), una joven y dotada oboísta, significará una gran oportunidad en su incipiente carrera como ejecutante. La segunda temporada de la serie continuará la tensión que dejó el impactante final de la primera entrega. -

Amazon to Debut the Highly-Anticipated Dramatic Comedy Mozart in the Jungle on 23Rd December in the UK, Germany and US

Amazon to Debut the Highly-Anticipated Dramatic Comedy Mozart in the Jungle on 23rd December in the UK, Germany and US November 20, 2014 All ten episodes will be available on Prime Instant Video Mozart in the Jungle stars Gael Garcia Bernal (Rosewater), Saffron Burrows (Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.), Hannah Dunne (Frances Ha), Lola Kirke (Gone Girl), and Peter Vack (I Just Want My Pants Back), and is Executive Produced by Roman Coppola (Moonrise Kingdom), Jason Schwartzman (The Darjeeling Limited), Paul Weitz (About a Boy), and John Strauss (There’s Something About Mary) Series guest stars include Malcolm McDowell (The Mentalist), Bernadette Peters (Smash), Debra Monk (Damages), Wallace Shawn (Gossip Girl), Mackenzie Leigh (General Hospital), Nora Arnezeder (Safe House), Jerry Adler (Good Wife), John Hodgman (Arthur), and Santino Fontana (Frozen) LONDON — 20th November 2014— Amazon today announced it will premiere all ten episodes of the highly-anticipated dramatic comedy series Mozart in the Jungle on Tuesday 23rd December on Prime Instant Video in the UK, Germany and US. Starring Gael Garcia Bernal (Rosewater), Saffron Burrows (Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.), Hannah Dunne (Frances Ha), Lola Kirke (Gone Girl), and Peter Vack (I Just Want My Pants Back), Mozart in the Jungle draws back the curtain at the New York Symphony, where artistic dedication and creativity collide with mind games, politicking and survival instincts. The series guest stars include Malcolm McDowell (The Mentalist) and Bernadette Peters (Smash), and is Executive Produced by Roman Coppola (Moonrise Kingdom), Jason Schwartzman (The Darjeeling Limited), Paul Weitz (About a Boy), and John Strauss (There’s Something About Mary). -

Mario Lavista

Música para charlar Música para charlar is the title of a piece by Silvestre Revueltas, and can be translated as “chit-chat” or “background music.” Hopefully, the music on this concert will mark the beginning of a fruitful dialogue between those who make music on both sides of the border: some small talk over the picket fence that separates our neighboring backyards or, as Revueltas would have liked it, a frank exchange of ideas over, let’s say, a few glasses of tequila. —Carlos Sanchez-Gutierrez This concert is made possible in part by major grants from the US-Mexico San Francisco Contemporary Music Players Fund for Culture and the Clarence E. Heller Charitable Foundation. We thank also the Zellerbach Family Fund and the William and Flora Hewlett Monday, May 13, 2002 at 8 pm Foundation for their support of this evening’s program. Center for the Arts Theater Carlos Sanchez-Gutierrez’s Clyde Beatty is Dead was commissioned with a grant from the Fromm Music Foundation at Harvard University, which has also helped to underwrite this premiere performance. Música para charlar JAVIER TORRES MALDONADO Performers Figuralmusik II (1996) U.S. Premiere Tod Brody, flute William Wohlmacher, clarinet RICARDO ZOHN-MULDOON Blair Tindall, oboe Danza Nocturna (1986, rev. 1989) Rufus Olivier, bassoon Gianna Abondolo, cello Lawrence Ragent, horn Julie Steinberg, piano Charles Metzger, trumpet I William Winant, percussion Ralph Wagner, trumpet II Hall Goff, trombone UAN RIGOS Peter Wahrhaftig, tuba J T Roy Malan, violin I Ricercare II (1993, rev. 1998) -

Berkeleysymphonyprogram2016

Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. We are now able to provide all funeral, cremation and celebratory services for our families and our community at our 223 acre historic location. For our families and friends, the single site combination of services makes the difficult process of making funeral arrangements a little easier. We’re able to provide every facet of service at our single location. We are also pleased to announce plans to open our new chapel and reception facility – the Water Pavilion in 2018. Situated between a landscaped garden and an expansive reflection pond, the Water Pavilion will be perfect for all celebrations and ceremonies. Features will include beautiful kitchen services, private and semi-private scalable rooms, garden and water views, sunlit spaces and artful details. The Water Pavilion is designed for you to create and fulfill your memorial service, wedding ceremony, lecture or other gatherings of friends and family. Soon, we will be accepting pre-planning arrangements. For more information, please telephone us at 510-658-2588 or visit us at mountainviewcemetery.org. Berkeley Symphony 2016/17 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 14 Season Sponsors 18 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 21 Program 23 Program Notes 35 Music Director: Joana Carneiro 39 Guest Conductor: Elim Chan 41 Artists’ Biographies 51 Berkeley Symphony 55 Music in the Schools 57 2016/17 Membership Benefits 59 Annual Membership Support 66 Broadcast Dates Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of 69 Contact Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. -

L O T H a R O S T E R B U

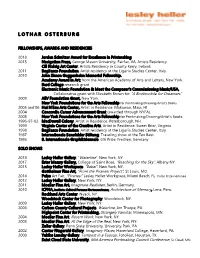

L O T H A R O S T E R B U R G FELLOWSHIPS, AWARDS AND RESIDENCIES 2018 Jordan Schnitzer Award for Excellence in Printmaking 2013 Navigation Press, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, Artists Residency. Cill Rialaig Art Center, Artists Residency in County Kerry, Ireland. 2011 Bogliasco Foundation, Artist residency at the Liguria Studies Center, Italy. 2010 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship. Academy Award in Art; from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York. Bard College research grant Electronic Music Foundation & Meet the Composer's Commissioning Music/USA, Collaborative grant with Elizabeth Brown for “A Bookmobile for Dreamers” 2009 AEV Foundation Grant, New York. New York Foundations for the Arts Fellowship for Printmaking/Drawing/Artist’s Books. 2005 and’06 Hui N’Eau Arts Center, Artist in Residence. Makawao, Maui, HI 2004 Concordia Career Advancement Grant (awarded through NYFA). 2003 New York Foundations for the Arts Fellowship for Printmaking/Drawing/Artist’s Books. 1996-97-02 MacDowell Colony, Artist in Residence. Peterborough, NH. 1999 Virginia Center of the Creative Arts, Artist in Residence. Sweet Briar, Virginia. 1998 Bogliasco Foundation, Artist residency at the Liguria Studies Center, Italy. 1987 Internationale Senefelder Stiftung, Traveling show of the Ten Best. 1986 8. Internationale Graphiktriennale, 6th Prize. Frechen, Germany. SOLO SHOWS 2018 Lesley Heller Gallery, “Waterline”. New York, NY. 2017 Ester Massry Gallery, College of Saint Rose, “Reaching for the Sky”, Albany NY. 2015 Lesley Heller Workspace, “Babel”. New York, NY. Gottheimer Fine Art, “From the Piranesi Project”, St Louis, MO. 2014 Pulse Art Fair, “Piranesi” Lesley Heller Workspace, Miami Beach, FL. -

The New York Times > Arts > Music > Better Playing Through Chemistry

Bron: http://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/17/arts/music/17tind.html October 17, 2004 Better Playing Through Chemistry By BLAIR TINDALL RUTH ANN McCLAIN, a flutist from Memphis, used to suffer from debilitating onstage jitters. "My hands were so cold and wet, I thought I'd drop my flute," Ms. McClain said recently, remembering a performance at the National Flute Convention in the late 1980's. Her heart thumped loudly in her chest, she added; her mind would not focus, and her head felt as if it were on fire. She tried to hide her nervousness, but her quivering lips kept her from performing with sensitivity and nuance. However much she tried to relax before a concert, the nerves always stayed with her. But in 1995, her doctor provided a cure, a prescription medication called propranolol. "After the first time I tried it," she said, "I never looked back. It's fabulous to feel normal for a performance." Ms. McClain, a grandmother who was then teaching flute at Rhodes College in Memphis, started recommending beta-blocking drugs like propranolol to adult students afflicted with performance anxiety. And last year she lost her job for doing so. College officials, who declined to comment for this article, said at the time that recommending drugs fell outside the student-instructor relationship and charged that Ms. McClain asked a doctor for medication for her students. Ms. McClain, who taught at Rhodes for 11 years, says she merely recommended that they consult a physician about obtaining a prescription. Ms. McClain is hardly the only musician to rely on beta blockers, which, taken in small dosages, can quell anxiety without apparent side effects. -

Amazon Renews 'Mozart in the Jungle' for Third Season

Search HOME FILM TV AWARDSLINE BOX OFFICE BUSINESS INTL VIDEO JOBS GOT A TIP? FILM BUSINESS TV FILM Johnny Depp Materializes In Hollywood Dems Eye Biden NBCUni Restructures Network ‘Fast 8’ Will Ride With A New Uni’s ‘Invisible Man’ Remake After New Hampshire Result Group & Top Execs Female Villain Amazon Renews ‘Mozart In The Jungle’ For Third Season ▶ TV ▶ BREAKING NEWS by Denise Petski ▶ AMAZON February 9, 2016 6:20am ▶ MOZART IN THE 3 JUNGLE USA Network Amazon has renewed Golden Globe-winning Mozart In The Jungle for a third season. Production will begin later this year. 'The Interestings': Jessica Collins & Corey Cott Join Related Amazon Drama Pilot Starring Gael García Bernal, Lola Kirke and Bernadette Peters, Mozart In The Jungle will continue the story of the talented, contentious musicians who perform (and live) with passion under the baton of its spirited single-name conductor Rodrigo (Bernal). Executive produced by Roman Coppola, Jason Schwartzman, Alex Timbers and Paul Weitz, Season 3 will see Rodrigo and many musicians take their talents to Europe. Based on Blair Tindall’s critically acclaimed memoir Mozart In The Jungle: Sex, Drugs & Classical Music, the series draws back the curtain at the New York Symphony, where artistic dedication and creativity collide with mind games, politicking and survival instincts. The series also stars Saffron Burrows, Malcolm McDowell, Hannah Dunne and Schwartzman. RECENT COMMENTS 4 hours HAP kerzondax It's been good at 12 hours 18 hours times, mostly in the Agree, and it's unlike BRILLIANT show. John Hodgeman arc, anything else on TV. ADD COMMENT but it's just as often 3 People Commenting corny..