Mitchell Black- Hyrule Warriors: Age of Calamity As Zelda's Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hyrule Warriors™ Es Un Juego De Acción Táctica Ambientado En El Universo De the Legend of Zelda™

Hyrule Warriors 1 Infor maci ón impo rtan te Cgonfi urnació 2 Coontr les y acce sori os 3 Func ion es en lín ea 4 Aviso para padres o tuto res Inicio 5 Acerca del jue go 6 Comenz ar a jug ar 7 Guar dar la parti da Comenzar la aventura 8 Selec ción de escenar io 9 Contro les básic os 10 Cont rol es de a taq ue WUP-P-BWPE-02 11 Pant all a prin cip al 12 Baat lsla 13 Bastion es y puestos de avanz ada 14 Anfieidead sl e emtn asled ya h biil dase 15 Ojtb ecoos enotan r dse ne l cmoa p de batlaal Hace rse más f uer te 16 Sidub r eil n ve 17 Aument ar la sal ud 18 Tnraiisrfe ra h bil deadtmsn e rae rsa 19 Caire r nsnsig ia 20 Caere r liix re s El mod o Aventu ra 21 Sobre el modo Av entu ra 22 Pantal la del ma pa 23 Bqús uesda 24 Lkvin s irastu le Cont eni do adic ion al 25 Contenido a dicional (de pa go) Acerc a de este pr oduc to 26 Asvi os laseg le Solución de problem as 27 Informaci ón de asisten cia 1 Infor maci ón impo rtan te Información importante Lee detenidamente este manual antes de usar este programa. Si un niño va a utilizar este programa, un adulto debe leerle y explicarle el contenido de este manual. Además, antes de usar este programa asegúrate de leer el contenido de la aplicación Información sobre salud y seguridad ( ) a la que puedes acceder desde el menú de Wii U. -

An Exploration of Zombie Narratives and Unit Operations Of

Acta Ludologica 2018, Vol. 1, No. 1 ABSTRACT: This document details the abstract for a study on zombie narratives and zombies as units and their translation from cinemas to interactive mediums. Focusing on modern zombie mythos and aesthetics as major infuences in pop-culture; including videogames. The main goal of this study is to examine the applications The Infectious Aesthetic of zombie units that have their narrative roots in traditional; non-ergodic media, in videogames; how they are applied, what are their patterns, and the allure of Zombies: An Exploration of their pervasiveness. of Zombie Narratives and Unit KEY WORDS: Operations of Zombies case studies, cinema, narrative, Romero, unit operations, videogames, zombie. in Videogames “Zombies to me don’t represent anything in particular. They are a global disaster that people don’t know how to deal with. David Melhart, Haryo Pambuko Jiwandono Because we don’t know how to deal with any of the shit.” Romero, A. George David Melhart, MA University of Malta Institute of Digital Games Introduction 2080 Msida MSD Zombies are one of the more pervasive tropes of modern pop-culture. In this paper, Malta we ask the question why the zombie narrative is so infectious (pun intended) that it was [email protected] able to successfully transition from folklore to cinema to videogames. However, we wish to look beyond simple appearances and investigate the mechanisms of zombie narratives. To David Melhart, MA is a Research Support Ofcer and PhD student at the Institute of Digital do this, we employ Unit Operations, a unique framework, developed by Ian Bogost1 for the Games (IDG), University of Malta. -

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for the Nine-Month Period Ended December 2013 (Briefing Date: 1/30/2014) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2010 FY3/2011 FY3/2012 FY3/2013 FY3/2014 Apr.-Dec.'09 Apr.-Dec.'10 Apr.-Dec.'11 Apr.-Dec.'12 Apr.-Dec.'13 Net sales 1,182,177 807,990 556,166 543,033 499,120 Cost of sales 715,575 487,575 425,064 415,781 349,825 Gross profit 466,602 320,415 131,101 127,251 149,294 (Gross profit ratio) (39.5%) (39.7%) (23.6%) (23.4%) (29.9%) Selling, general and administrative expenses 169,945 161,619 147,509 133,108 150,873 Operating income 296,656 158,795 -16,408 -5,857 -1,578 (Operating income ratio) (25.1%) (19.7%) (-3.0%) (-1.1%) (-0.3%) Non-operating income 19,918 7,327 7,369 29,602 57,570 (of which foreign exchange gains) (9,996) ( - ) ( - ) (22,225) (48,122) Non-operating expenses 2,064 85,635 56,988 989 425 (of which foreign exchange losses) ( - ) (84,403) (53,725) ( - ) ( - ) Ordinary income 314,511 80,488 -66,027 22,756 55,566 (Ordinary income ratio) (26.6%) (10.0%) (-11.9%) (4.2%) (11.1%) Extraordinary income 4,310 115 49 - 1,422 Extraordinary loss 2,284 33 72 402 53 Income before income taxes and minority interests 316,537 80,569 -66,051 22,354 56,936 Income taxes 124,063 31,019 -17,674 7,743 46,743 Income before minority interests - 49,550 -48,376 14,610 10,192 Minority interests in income -127 -7 -25 64 -3 Net income 192,601 49,557 -48,351 14,545 10,195 (Net income ratio) (16.3%) (6.1%) (-8.7%) (2.7%) (2.0%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games

The Princess and the Platformer: The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games Katharine Phelps Humanities 497W December 15, 2007 Just remember that my being a woman doesn't make me any less important! --Faris Final Fantasy V 1 The Princess and the Platformer: The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games Female characters, even as a token love interest, have been a mainstay in adventure games ever since Nintendo became a household name. One of the oldest and most famous is the princess of the Super Mario games, whose only role is to be kidnapped and rescued again and again, ad infinitum. Such a character is hardly emblematic of feminism and female empowerment. Yet much has changed in video games since the early 1980s, when Mario was born. Have female characters, too, changed fundamentally? How much has feminism and changing ideas of women in Japan and the US impacted their portrayal in console games? To address these questions, I will discuss three popular female characters in Nintendo adventure game series. By examining the changes in portrayal of these characters through time and new incarnations, I hope to find a kind of evolution of treatment of women and their gender roles. With such a small sample of games, this study cannot be considered definitive of adventure gaming as a whole. But by selecting several long-lasting, iconic female figures, it becomes possible to show a pertinent and specific example of how some of the ideas of women in this medium have changed over time. A premise of this paper is the idea that focusing on characters that are all created within one company can show a clearer line of evolution in the portrayal of the characters, as each heroine had her starting point in the same basic place—within Nintendo. -

Fall 2014 Concert Series

Fall 2014 ConCert SerieS NIGEL HORNE, MUSIC DIRECTOR LAURA STAYMAN, CONCERT LEADER Saturday, December 13 - Herndon, VA Saturday, December 20 - Rockville, MD [Classical Music. Play On!] WMGSO.org | @WMGSO | fb/MetroGSO about the WMGSo The WMGSO is a community orchestra and choir whose mis- sion is to share and celebrate video game music with as wide an audience as possible, primarily by putting on affordable, accessi- ble concerts in the area. Game music weaves a complex, melodic thread through the traditions, values, and mythos of an entire culture, and yet it largely escapes recognition in professional circles. Game music has powerful meaning to millions of people. In it, we find deep emotion and basic truths about life. We find ourselves — and we find new ways of thinking about and expressing ourselves. We find meaning that transcends the medium itself and stays with us for life. WMGSO showcases this emerging genre and highlights its artistry. Incorporated in December 2012, WMGSO grew from the spirit of the GSO at the University of Maryland. About a dozen members showed up at WMGSO’s inaugural rehearsal. Since then, the group has grown to more than 60 musicians. The WMGSO’s debut at Rockville High School in June attracted an audience of more than 500. Also in June, the IRS accepted WMGSO’s appli- cation to become a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization, opening even more opportunities for the orchestra to grow. adMiniStration Music Director, Nigel Horne Chorusmaster, Jacob Coppage-Gross President, Ayla Hurley Vice President, Joseph Wang Secretary, Laura Stayman Treasurer, Chris Apple Public Relations, Robert Garner Webmaster, Jason Troiano Event Coordinator, Diana Taylor Assistant Treasurer, Patricia Lucast supporters From securing rehearsal space and equipment rentals, to print- ing concert programs and obtaining music licenses, we rely on the support of our members and donors. -

Concert: Ithaca College Gamer Symphony Orchestra Vivian Becker

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 11-1-2017 Concert: Ithaca College Gamer Symphony Orchestra Vivian Becker Raul Dominguez Keehun Nam Henry Scott mithS Ithaca College Gamer Symphony Orchestra Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Becker, Vivian; Dominguez, Raul; Nam, Keehun; Smith, Henry Scott; and Ithaca College Gamer Symphony Orchestra, "Concert: Ithaca College Gamer Symphony Orchestra" (2017). All Concert & Recital Programs. 4072. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/4072 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College Gamer Symphony Orchestra Conductors: Vivian Becker Raul Dominguez Keehun Nam Henry Scott Smith Ford Hall Wednesday, November 1st, 2017 8:15 pm Program Kid Icarus (1986) Hirokazu Ando arr. Jeremy Werner Vivian Becker, Conductor The Great Journey: Themes from the Martin O'Donnell & Michael Halo Series (2001) Salvatori arr. Nicolas Chlebak Henry Scott Smith, Conductor Prayers in the Temple of Time (1998) Koji Kondo arr. Rebecca Tripp Raul Dominguez, Conductor Fantasy for Kirby (1992) Jun Ishikawa & Hirokazu Ando arr. Alexander Rosetti Vivian Becker, Conductor "Remix 10" Clinton Edward Strother & Tsunku from Rhythm Heaven Fever (2011) arr. Frankie DiLello Henry Scott Smith, Conductor Intermission Monster Hunter: Proof of a Hero (2004) Masato Kouda arr. Griffin Charyn Vivian Becker, Conductor "Oh! One True Love" Toby Fox from Undertale (2015) arr. Anna Marcus-Hecht Raul Dominguez, Conductor Selections from Ninja Gaiden (1988) Mikio Saitou, Ichiro Nakagawa, Ryuichi Nitta, Tamotsu Ebisawa arr. -

Game Review | the Legend of Zelda file:///Users/Denadebry/Desktop/Hpsresearch/Papersfromgreen

Game Review | The Legend of Zelda file:///Users/denadebry/Desktop/HPSresearch/PapersFromGreen... Matt Waddell STS 145: Game Review Table of Contents: Da Game Story Line & Game-play Technical Stuff Game Design Success Endnotes In 1984 President Hiroshi Yamauchi asked apprentice game designer Sigeru Miyamoto to oversee R&D4, a new research and development team for Nintendo Co., Ltd. Miyamoto's group, Joho Kaihatsu, had one assignment: "to come up with the most imaginative video games ever." 1 On February 21, 1986, Nintendo Co., Ltd. published The Legend of Zelda (hereafter abbreviated LoZ) for the Famicom in Japan. It was Miyamoto's first autonomous attempt at game design. In July 1987, Nintendo of America published LoZ for the Nintendo Entertainment System in the United States, this time with a shiny gold cartridge. Origins: where did LoZ come from? Miyamoto admits that LoZ is partly based on Ridley Scott's movie Legend. Indeed, Miyamoto's video game shares more than just a title with Scott's 1985 production. But Miyamoto's fundamental inspiration for LoZ remains his childhood home, with its maze of rooms, sliding shoji screens, and "hallways, from which there seemed to be a medieval castle's supply of hidden rooms." 2 Story Line: a brief synopsis. In the land of Hyrule, the legend of the "Triforce" was being passed down from generation to generation; golden triangles possessing mystical powers. One day, an evil army attacked Hyrule and stole the Triforce of Power. This army was led by Gannon, the powerful Prince of Darkness. Fearing his wicked rule, Zelda, the princess of Hyrule, split the remaining Triforce of Wisdom into eight fragments and hid them throughout the land. -

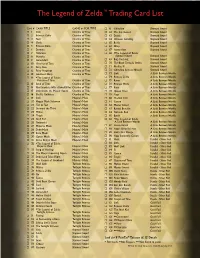

The Legend of Zelda™ Trading Card List

The Legend of Zelda™ Trading Card List Card # CARD TITLE GAME or FOIL TYPE ¨ 61 Ghirahim Skyward Sword ¨ 1 Link Ocarina of Time ¨ 62 The Imprisoned Skyward Sword ¨ 2 Princess Zelda Ocarina of Time ¨ 63 Demise Skyward Sword ¨ 3 Navi Ocarina of Time ¨ 64 Crimson Loftwing Skyward Sword ¨ 4 Sheik Ocarina of Time ¨ 65 Beetle Skyward Sword ¨ 5 Princess Ruto Ocarina of Time ¨ 66 Whip Skyward Sword ¨ 6 Darunia Ocarina of Time ¨ 67 Scattershot Skyward Sword ¨ 7 Twinrova Ocarina of Time ¨ 68 *The Legend of Zelda: ¨ 8 Morpha Ocarina of Time Skyward Sword Skyward Sword ¨ 9 Ganondorf Ocarina of Time ¨ 69 Bug Catching Skyward Sword ¨ 10 Ocarina of Time Ocarina of Time ¨ 70 The Black Tornado Strikes Skyward Sword ¨ 1 1 Fairy Bow Ocarina of Time ¨ 7 1 Finding Fi Skyward Sword ¨ 12 Fairy Slingshot Ocarina of Time ¨ 72 Ghirahim Reveals Himself Skyward Sword ¨ 13 Goddess’s Harp Ocarina of Time ¨ 73 Link A Link Between Worlds ¨ 14 *The Legend of Zelda: ¨ 74 Princess Zelda A Link Between Worlds Ocarina of Time Ocarina of Time ¨ 75 Ravio A Link Between Worlds ¨ 15 Song of Time Ocarina of Time ¨ 76 Princess Hilda A Link Between Worlds ¨ 16 First Encounter With a Powerful Foe Ocarina of Time ¨ 77 Irene A Link Between Worlds ¨ 17 Link Draws the Master Sword Ocarina of Time ¨ 78 Queen Oren A Link Between Worlds ¨ 18 Sheik’s Guidance Ocarina of Time ¨ 79 Yuga A Link Between Worlds ¨ 19 Link Majora’s Mask ¨ 80 Shadow Link A Link Between Worlds ¨ 20 Happy Mask Salesman Majora’s Mask ¨ 8 1 Ganon A Link Between Worlds ¨ 2 1 Tatl & Tael Majora’s Mask ¨ 82 Master Sword -

Wind Waker Manual

OFFICIAL NINTENDO POWER PLAYER'S GUIDE AVAILABLE AT YOUR NEAREST RETAILER! WWW.NINTENDO.COM Nintendo of America Inc. P.O. Box 957, Redmond, WA 98073-0957 U.S.A. www.nintendo.com IN S T R U C T IO N B O O K LET 50520A IN S T R U C T IO N B O O K LET PRINTED IN USA W A R N IN G : P L E A S E C A R E FU L L Y R E A D T HE S E P A R A T E P R E C A U T IO N S B O O K L E T IN C L U D E D W IT H T HIS P R O D U C T WARNING - Electric Shock B E FO R E U S IN G Y O U R N IN T E N D O ® HA R D W A R E S Y S T E M , To avoid electric shock when you use this system: G A M E D IS C O R A C C E S S O R Y . T HIS B O O K L E T C O N T A IN S IM P O R T A N T S A FE T Y IN FO R M A T IO N . Use only the AC adapter that comes with your system. Do not use the AC adapter if it has damaged, split or broken cords or wires. -

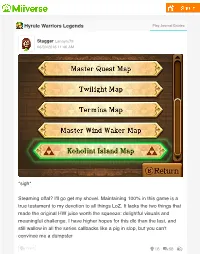

I'll Go Get My Shovel. Maintaining 100% in This Game Is a True Testament to My Devotion to All Things Loz

Hyrule Warriors Legends Play Journal Entries Stagger Lanayru79 06/30/2016 11:46 AM *sigh* Steaming offal? I'll go get my shovel. Maintaining 100% in this game is a true testament to my devotion to all things LoZ. It lacks the two things that made the original HW juice worth the squeeze: delightful visuals and meaningful challenge. I have higher hopes for this dlc than the last, and still wallow in all the series callbacks like a pig in slop, but you can't convince me a dumpster E Yeah! e 16 r 68 D Advertisement Share this Post 1 Tweet 2 Share Embed Comment Stagger 06/30/2016 11:49 AM fire is pretty or beneficial no matter what you add to the blaze. Fortunately, I'm at a nice stopping point in Ni no Kuni. Otherwise I'd put off savagely shredding another map even more than a work weekend and a few imminent errands will delay the assault. Hate away, HWL supporters. The only argument I can see that supports the existence of this hogwash is poverty or reluctance to own a Wii U. E Yeah! e 1 D Sciz 06/30/2016 1:59 PM Notifications, maybe? At least Marin's interesting. Wind Fish! E Yeah! e 2 D Ed™ 06/30/2016 2:07 PM I'd take a dumpster fire over a Christmas tree, but that's probably just my Southern upbringing talking. I'll admit, the LA DLC has generated more interest for me than anything in HW thus far. Not enough to make me get the game, but enough that I wouldn't mind notifs if this turns into a log. -

Game Narrative Review

Game Narrative Review ==================== Your name (one name, please): Mostafa Haque Your school: New York University Your email: [email protected] Month/Year you submitted this review: December 2017 ==================== Game Title: The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild Platform: Nintendo Switch/Wii U Genre: Action-Adventure Release Date: March 3rd, 2017 Developer: Nintendo EPD Publisher: Nintendo Director: Hidemaro Fujibayashi Game Writer: Akihito Toda Overview Deep inside an ancient shrine, the Eternal Hero of Hyrule awakens to a familiar voice, calling out across time and space. A century of slumber may have muddled his mind, but there is one thing Link is still certain of. Princess Zelda calls for aid, and neither the great Calamity nor death itself will keep her Champion from her. Despite being around for over thirty years, The Legend of Zelda series continues to engage audiences with its latest installment, Breath of the Wild (BotW). Using a carefully sculpted world, interlinking low-level systems, and non-sequential exploration of the Monomyth, BotW manages to transfer ownership of authored story moments to the players themselves – integrating carefully designed narrative progression with the type of emergence at which open world games excel. Characters • Zelda – Fiercely independent, inquisitive, and dutiful, the franchise’s eponymous princess returns as the deuteragonist of Breath of the Wild. Unable to completely control the magical powers granted to her as the avatar of the goddess Hylia, Zelda resorted to studying and utilizing ancient technology to combat the inevitable return of Calamity Ganon. A stark contrast to her saintlier incarnations, this version of Hyrule’s princess is initially portrayed as skeptical towards her people’s faith – often to the point of agnosticism - despite, or perhaps because of, her alleged role as a divine vessel.