Religious Reversion in the Brethren in Christ Church in Zimbabwe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Matebeleland South

HWANGE WEST Constituency Profile MATEBELELAND SOUTH Hwange West has been stripped of some areas scene, the area was flooded with tourists who Matebeleland South province is predominantly rural. The Ndebele, Venda and the Kalanga people that now constitute Hwange Central. Hwange contributed to national and individual revenue are found in this area. This province is one of the most under developed provinces in Zimbabwe. The West is comprised of Pandamatema, Matesti, generation. The income derived from tourists people feel they have been neglected by the government with regards to the provision of education Ndlovu, Bethesda and Kazungula. Hwange has not trickled down to improve the lives of and health as well as road infrastructure. Voting patterns in this province have been pro-opposition West is not suitable for human habitation due people in this constituency. People have and this can be possibly explained by the memories of Gukurahundi which may still be fresh in the to the wild life in the area. Hwange National devised ways to earn incomes through fishing minds of many. Game Park is found in this constituency. The and poaching. Tourist related trade such as place is arid, hot and crop farming is made making and selling crafts are some of the ways impossible by the presence of wild life that residents use to earn incomes. destroys crops. Recreational parks are situated in this constituency. Before Zimbabwe's REGISTERED VOTERS image was tarnished on the international 22965 Year Candidate Political Number Of Votes Party 2000 Jelous Sansole MDC 15132 Spiwe Mafuwa ZANU PF 2445 2005 Jelous Sansole MDC 10415 Spiwe Mafuwa ZANU PF 4899 SUPPORTING DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS 218 219 SUPPORTING DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS BULILIMA WEST Constituency Profile Constituency Profile BULILIMA EAST Bulilima West is made up of Dombodema, residents' incomes. -

Zimbabwean \ Government Gazette

c,-"' 'ik."4 V' A ZIMBABWEAN \ GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority Vol. LXXI, 1^0. 60 24th SEPTEMBER, 1993 Fhice 2,50 General Notice 569 of 1993. Commencing At its junction with Majoni Road (33/171) and stands 85 and 81. ROADS ACT [CHAPTER 263] Passing through Application for Declaration of Branch Roads: Habane Township Stand Nos. 85,84, 83, 82,431 and 81. Terminating IT is hereby notified, in terms of subsection (3) of section 6 of the At its junction with Robert Mkandla Road (33/177) and stands Roads Act [Chapter 263], that application has been made for the 110 and 432. roads described hereunder, and shown on Provincial Plan RC 33/29/D to be branch roads. Reference Plan RC 23/29/D may be inspected, free of charge, at the offices 33/174 Ngubo Road. of the Secretary for Transport, Kaguvi Building, Fourth Street, Commencing Harare. At its junction with Majoni Moyo Road (33/171) and stands 92 Description of road and 117. Reference Passing through 33/170 Mtonzima Gwebu Road. Stand Nos. 93,94, 95, 115, 116, 118,119, 120, 121, 122 and 123. Commencing TermitMting 1 At its junction with Stella Coulson Road (33/104). On Stand No. 124. Passing through Reference Stand Nos. 2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, 19, 20,483,484, 22,23, 24,25, 26, 27,28,29, 30,31,32, 33, 33/175 Mtshede Road. 34, 35 and 36. Commencing Terminating At its junction with Majoni Moyo Road (33/171) and stands 125 and 109. -

Provisional Constitutional Referendum Polling Stations 16 March 2013 Matabeleland South Province

Matabeleland South Provisional Constitutional Referendum Polling Stations 16 March 2013 Matabeleland South Province DISTRICT CONSTITUENCY LOCAL AUTHORITY WARD# POLLING STATIONS FACILITY Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 1 Chikwalakwala Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 1 Chipise Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 1 Chitulipasi Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 1 Lungowe Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 1 Malabe Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 2 Chabili Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 2 Chapongwe Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 2 Dite Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 2 Lukumbwe Dip Tank Tent Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 2 Panda Mine Tent Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 2 Lukange Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 3 Chaswingo Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 3 Fula Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 3 Madaulo Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 3 Makombe Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 3 Mandate Primary School Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge West Beitbridge RDC 4 Jopembe Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge West Beitbridge RDC 4 Mgaladivha Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge West Beitbridge RDC 4 Manazwe Area Tent Beitbridge Beitbridge West Beitbridge RDC 4 Matshiloni Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge -

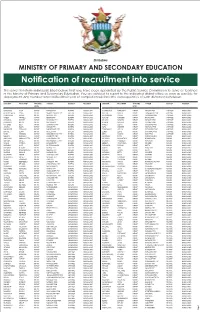

Zimlive – New Teacher Recruits

NOTIFICATION OF RECRUITMENT INTO SERVICE This serves to inform individuals listed below, that you have been appointed by the Public Service Commission to serve as teachers in the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education. You are advised to report to the indicated district office as soon as possible for deployment. T. -

Literature Review

UNIVERSITY OF ZIMBABWE Impact and sustainability of drip irrigation kits, in the semi-arid Lower Mzingwane Catchment, Limpopo Basin, Zimbabwe By Richard Moyo A thesis submitted to the University of Zimbabwe (Faculty of Engineering, Department of Civil Engineering) in partial fulfilment of requirements of Master of Science in Water Resources Engineering and Management ABSTRACT Smallholder farmers in the Mzingwane Catchment are confronted with low food productivity due to erratic rainfall and limitations to appropriate technologies. Several drip kit distribution programs were carried out in Zimbabwe as part of a global initiative aimed at 2 million poor households a year to take major step on the path out of poverty. Stakeholders have raised concerns of limitations to conditions necessary for sustainable usage of drip kits, such as continuing availability of minimum water requirement. Accordingly, a study was carried out to assess the impacts and sustainability of the drip kit program in relation to water availability, access to water and the targeting of beneficiaries. Representatives of the NGOs, local government, traditional leadership and agricultural extension officers were interviewed. Drip kit beneficiaries took part in focus group discussions that were organised on a village basis. A survey was then undertaken over 114 households in two districts, using a questionnaire developed from output of the participatory work. Data were analysed using SPSS. The results from the study show us that not only poor members of the community (defined for the purpose of the study as those not owning cattle), accounting for 54 % of the beneficiaries. This could have been a result of the condition set by some implementing NGOs that beneficiaries must have an assured water source - which is less common for poorer households. -

Archdiocese of Bulawayo Pastoral Directory 2020

ARCHDIOCESE OF BULAWAYO PASTORAL DIRECTORY 2020 SUBURB PARISH/ MISSION-Nov. 2019 ADDRESS TEL. email 108a Ninth Avenue Lobengula (029) 1 BULAWAYO CITY ARCHBISHOP'S HOUSE Street Bulawayo 63590 [email protected] P.O. Box 837 Bulawayo [email protected] [email protected] 109a Ninth Avenua Lobengula (029) 2 ST. MARY'S CATHEDRAL BASILICA Street Bulawayo 69572 [email protected] (029) P.O. Box 837 BULAWAYO 60889 (029) 2a DOMINICAN CONVENT P.O. BO 530 BULAWAYO 61485 DOMINICAN CONVENT PRIMARY (029) 2b SCHOOL P.O. BOX 530 BULAWAYO 77687 [email protected] DOMINICAN CONVENT GIRLS HIGH (029) 2c SCHOOL P.O. BOX 530 BULAWAYO 66235 [email protected] (029) 2d A.M.R. CONVENT P.O. BOX 837 BULAWAYO 60889 27 VOLSHENK DRIVE BARHAM (029) 246 3 BARHAM GREEN ST. ANTHONY'S PARISH GREEN 9652 (029) 247 3a S.M.I. HOUSE 8479 P.O. LLEWLLYN BARRACKS 4 THE BARRACKS ST. CHRISTOPHER BULAWAYO 5 COWDREY PARK HOLY TRINITY P.O. BOX 18 LUVEVE BULAWAYO 6 EMAKHANDENI ST. PADRE PIO 4266 EMAKHANDENI P.O. BOX 23 ENTUMBANE BULAWAYO 7 EMGANWINI ST. MARTIN OF TOURS 2442 EMGANWINI BULAWAYO (029) 248 0144 (029) 8 ENTUMBANE OUR LADY QUEEN OF PEACE P.O. BOX 100 ENTUMBANE BYO 241 004 Mass Centre : St. Francis 9 FAIRBRIDGE ST. IGNATIUS P.O. BOX 9006 HILLSIDE (029) 224 10 HILLSIDE CHRIST THE KING BULAWAYO 1187 [email protected] P.O. BOX 9315 HILLSIDE (029) 224 10a F.M.D.M. CONVENT BULAWAYO 0007 [email protected] 3 CHESTERTON ROAD MALINDELA BULAWAYO 11 BYRON ROAD MALINDELA (029) 224 10b A.M.R. -

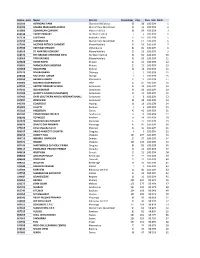

Zimbabwegrade7passrates A4

Centre_num Name District _Candidates Pass_ Pass_rate Rank 015100 ASPINDALE PARK Glenview Mufakose 38 38 100.00% 1 015785 DIVARIS MAKAHARIS JUNIOR Warren Park Mabelreign 16 16 100.00% 2 015800 DOMINICAN CONVENT Mbare Hatfield 69 69 100.00% 3 016130 HAPPY PRIMARY Northern Central 9 9 100.00% 4 017120 LUSITANIA Mabvuku Tafara 51 51 100.00% 5 017250 MARANATHA Warren Park Mabelreign 61 61 100.00% 6 017390 MOTHER PATRICK CONVENT Mbare Hatfield 53 53 100.00% 7 017590 PATHWAY PRIVATE Chitungwiza 60 60 100.00% 8 018160 ST. MARTINS CONVENT Mbare Hatfield 35 35 100.00% 9 018470 THE GRANGE CHRISTIAN SCHO Northern Central 50 50 100.00% 10 018560 TWO BRIGADE Mbare Hatfield 69 69 100.00% 11 025828 CROSS KOPJE Mutare 21 21 100.00% 12 026692 MANICALAND CHRISTIAN Mutare 15 15 100.00% 13 027008 MILESTONE Makoni 18 18 100.00% 14 027575 MVURACHENA Chipinge 5 5 100.00% 15 028400 MUTARAZI JUNIOR Nyanga 6 6 100.00% 16 035050 BARNIES JUNIOR Marondera 11 11 100.00% 17 035060 BEATRICE GOVERNMENT Seke 47 47 100.00% 18 035722 DESTINY PRIMARY SCHOOL Goromonzi 14 14 100.00% 19 037242 OLD WINDSOR Goromonzi 94 94 100.00% 20 037308 QUALITY JUNIOR (RUVHENEKO) Goromonzi 19 19 100.00% 21 037482 SAISS (SOUTHERN AFRICA INTERNATIONAL) Goromonzi 8 8 100.00% 22 037897 WINDVIEW Goromonzi 38 38 100.00% 23 045300 COALFIELDS Hwange 18 18 100.00% 24 055002 ALLETTA Kwekwe 6 6 100.00% 25 055010 ANDERSON Gweru 42 42 100.00% 26 057432 PAMAVAMBO PRIVATE Zvishavane 13 13 100.00% 27 058030 TORWOOD Kwekwe 54 54 100.00% 28 067670 NGOMAHURU PRIMARY Masvingo 27 27 100.00% 29 068870 ZIMUTO ZRP -

Evolution of Social Science Research at ICRISAT, and a Case Study in Zimbabwe

An Open Access Journal published by ICRISAT ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Evolution of Social Science Research at ICRISAT, and a Case Study in Zimbabwe Jane D Alumira, Ma Cynthia S Bantilan and Tinah Sihoma-Moyo SAT eJournal | ejournal.icrisat.org December 2007 | Volume 3 | Issue 1 An Open Access Journal published by ICRISAT ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Evolution of Social Science Research at ICRISAT Background Social science research (SSR) at ICRISAT evolved in the context of its socio-economics program, covering agricultural economics, science and technology policy, rural sociology, and anthropology (Byerlee 2001). These disciplines play complementary roles in obtaining a basic understanding of the rural economy in the semi-arid tropics (SAT), identifying priorities for research, informing policy, monitoring research impacts and helping to direct investments by ICRISAT’s partners. The first part of this paper analyzes the evolution of SSR in ICRISAT. The second part is a recent case study on livelihood diversification behavior among smallholder farm communities in Zimbabwe. It illustrates how SSR contributes to livelihood analysis, targeting of research and development, and informing policy. The structure and content of SSR at ICRISAT has been shaped by the Institute’s overall research strategies over time. Before 1996, ICRISAT’s major emphasis was on increasing production and food security through new technologies and new uses for our mandate crops. The strategy focused on more efficient use of small quantities of inputs and their timely application to enrich nutrient-poor soils. In the latter half of the 1990s, there was renewed effort on problem-based, impact-driven science and delivery of outputs. By 1997, the Institute’s strategy aimed to identify alternative uses of the natural resource base that could help reduce poverty, promote food security, and prevent environmental degradation. -

Evolution of Social Science Research at ICRISAT, and a Case Study in Zimbabwe

Working Paper Series no. 20 Socioeconomics and Policy Evolution of Social Science Research at ICRISAT, and a Case Study in Zimbabwe Jane D Alumira, Ma. Cynthia S Bantilan and Tinah Sihoma-Moyo ICRISAT International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics PO Box 776, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe www.icrisat.org International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics 596-2004 Citation: Alumira JD, Bantilan MCS, and Sihoma-Moyo T. 2005. Evolution of social science research at ICRISAT, and a case study in Zimbabwe. Working Paper Series no. 20. PO Box 776, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe: International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics. 28 pp. Titles in the Working Paper Series aim to disseminate information and stimulate feedback from the scientific community. A large number of similar and informal publications, derived from ICRISAT’s socio-economics and policy research, are also being distributed under various titles: Impact Series, Policy Briefs, Progress Reports, Discussion Papers, and Occasional Papers. Abstract About ICRISAT This paper consists of two distinct yet complementary parts. The first part analyzes the evolution of social science research (SSR) at ICRISAT. It describes the initiation of SSR, its continued recognition and incorporation in the Institute’s research strategy, its structure, staff strength, collaboration and partnerships; and the constraints faced by The semi-arid tropics (SAT) encompass parts of 48 developing countries including most of India, SSR – including debates on relevance and performance, and how these have been dealt with within the Institute. The parts of Southeast Asia, a swathe across sub-Saharan Africa, much of southern and eastern Africa, second part was motivated by the CGIAR’s thrust to enhance the contribution of SSR to sustainable agricultural and parts of Latin America. -

Notification of Recruitment Into Service

Zimbabwe Notification of recruitment into service This serves to inform individuals listed below, that you have been appointed by the Public Service Commission to serve as teachers in the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education. You are advised to report to the indicated district office as soon as possible for deployment. Any member who falsified their year of completion will face the consequences of such dishonest behaviour. -

Matabeleland South Inspection Centres

MATABELELAND SOUTH INSPECTION CENTRES BEITBRIDGE CONSTITUENCY 1 BEITBRIDGE DISTRICT REGISTRY 2 BEITBRIDGE MISSION PRIMARY SCHOOL 3 CHABETA PRIMARY SCHOOL 4 CHABILI PRIMARY SCHOOL 5 CHAMNANGA PRIMARY SCHOOL 6 CHAMNANGANA PRIMARY SCHOOL 7 CHAPFUCHE PRIMARY SCHOOL 8 CHASVINGO PRIMARY SCHOOL 9 CHITURIPASI PRIMARY SCHOOL 10 DITE PRIMARY SCHOOL 11 DUMBA PRIMARY SCHOOL 12 LIMPOPO PRIMARY SCHOOL 13 LUHWADE PRIMARY SCHOOL 14 LUTUMBA PRIMARY SCHOOL 15 MADAULO PRIMARY SCHOOL 16 MAKABULE PRIMARY SCHOOL 17 MAKOMBE PRIMARY SCHOOL 18 MALALA PRIMARY SCHOOL 19 MTETENGWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 20 MTSHILASHOKWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 21 MGALADIVHA PRIMARY SCHOOL 22 NULI (SHABWE) PRIMARY SCHOOL 23 MATSHILONI PRIMARY SCHOOL 24 RUKANGE PRIMARY SCHOOL 25 SHASHI PRIMARY SCHOOL 26 SWEREKI PRIMARY SCHOOL 27 TONGWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 28 TOPORO PRIMARY SCHOOL 29 WHUNGA PRIMARY SCHOOL 30 ZEZANI SECONDARY SCHOOL 31 VHEMBE SECONDARY SCHOOL 32 BEITBRIDGE GVT PRIMARY SCHOOL 33 MOBILE 1 i) DENDELE PRIMARY SCHOOL 19/11-22/11 ii) MADALI PRIMARY SCHOOL 23/11-26/11 iii) BWEMURA PRIMARY SCHOOL 27/11-30/11 iv) MASUNGANE PRIMARY SCHOOL 01/12-04/12 v) MSANE PRIMARY SCHOOL 05/12-09/12 34 MOBILE 2 i) CHIKWARAKWARA PRIMARY SCHOOL 19/11-23/11 ii) CHIPISE PRIMARY SCHOOL 24/11-28/11 iii) MALABE PRIMARY SCHOOL 29/11-03/12 iv) FULA PRIMARY SCHOOL 04/12-09/12 35 MOBILE 3 i) CHAPONGWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 19/11-22/11 ii) MAPAYI PRIMARY SCHOOL 23/11-26/11 iii) PENEMENE PRIMARY SCHOOL 27/11-01/12 iv) LESANTH RANCH 02/12-05/12 v) BUBI VILLAGE 06/12-09/12 36 MOBILE 4 i) AURIDIUM MINE 19/11-22/11 ii) NOTTINGHAM ESTATES -

Matabeleland South

Matabeleland South DISTRICT CONSTITUENCY LOCAL AUTHORITY WARD# POLLING STATIONS FACILITY Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 1 Chikwarakwara Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 1 Chipise Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 1 Chitulipasi Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 1 Lungowe Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 1 Malabe Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 2 Chabili Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 2 Chapongwe Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 2 Dite Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 2 Likumbwe Dip Tank Tent Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 2 Panda Mine Tent Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 2 Lukange Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 3 Chaswingo Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 3 Fula Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 3 Madaulo Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 3 Makombe Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge East Beitbridge RDC 3 Mandate Primary School Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge West Beitbridge RDC 4 Jopembe Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge West Beitbridge RDC 4 Magaladivha Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge West Beitbridge RDC 4 Manazwe Area Tent Beitbridge Beitbridge West Beitbridge RDC 4 Matshiloni Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge West Beitbridge RDC 4 Penemene Primary School Beitbridge Beitbridge West Beitbridge RDC 4 Tongwe