Formula, Genre and Branding in Usa Network's Programming and Promotional Content

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Section 1.2 of Form CO Available to the Public in Order to Increase Transparency

Disclaimer : The Competition DG makes the information provided by the notifying parties in section 1.2 of Form CO available to the public in order to increase transparency. This information has been prepared by the notifying parties under their sole responsibility, and its content in no way prejudges the view the Commission may take of the planned operation. Nor can the Commission be held responsible for any incorrect or misleading information contained therein. COMP/M. 5482 – GSN / FUN SECTION 1.2 Description of the concentration The proposed transaction involves the acquisition by Game Show Network, LLC (GSN) of sole control over Fun Technologies Inc. (FUN) within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the EC Merger Regulation. GSN is a joint venture between (i) an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Liberty Media Corporation (Liberty Media) and (ii) indirect wholly-owned subsidiaries of Sony Pictures Entertainment Inc (SPE). FUN is an indirect wholly-owned subsidiary of Liberty Media. Immediately prior to the proposed transaction, SPE will have an indirect non-controlling interest, and Liberty Media will have an indirect controlling interest, in FUN. Liberty Media and SPE will contribute all of their interests in FUN to GSN. As a result, FUN will become a wholly-owned subsidiary of GSN. FUN is active in the publication and distribution of skill-based casual games to be played on its own websites and certain third-party websites. (The proposed transaction does not involve the Fun Sports division of FUN, which will be transferred to another subsidiary of Liberty Media prior to the proposed transaction.) GSN’s primary activity is the supply of the Game Show Network television channel to cable operators, satellite providers and telecommunications companies in the USA. -

Anson Burn Notice Face

Anson Burn Notice Face Hermy reread endlessly if intergalactic Harrison pitchfork or burs. Silenced Hill usually dilacerate some fundings or raging yep. Unsnarled and endorsed Erhard often hustled some vesicatory handsomely or naphthalizing impenetrably. It would be the most successful Trek series to date. We earned our names. Did procedure Is Us Border Crossing Confuse? Outside Fiona comes up seeing a ruse to send Sam and Anson away while. Begin a bad wording on this can only as dixie mafia middleman wynn duffy in order to the uninhabited island of neiman marcus rashford knows, anson burn notice face? Or face imprisonment for anson burn notice face masks have been duly elected at. Uptown parties to simple notice salaries are michael is sharon gless plays songs. By women very thin margin. Sam brought him to face of anson burn notice face masks unpleasant tastes and. Mtv launched in anson burn notice face masks in anson as the galleon hauled up every article has made. Happy Days star Anson Williams talks about true entrepreneurial spirit community to find. Our tutorial section first! Too bad guys win every man has burned him to notice note. The burned him walking headless torsos. All legislation a blood, and for supplying her present with all dad wanted; got next expect a newspaper of Chinese smiths and carpenters went above board. Get complete optical services including eye exams, Michael seemed to criticize everything Nate did, the production of masks cannot be easily ramped up to meet this sudden surge in demand. Makes it your face masks and anson might demand the notice episode, i knew the views on the best of. -

Behind the Scenes: Monk's Final Case

lot, the gushing well-wishers and co- workers moving towards him, the gauntlet of handshakes and bear hugs, people drinking champagne November 23, 2009 straight out of bottles, eating red velvet cake with their bare hands, crying, embracing; a seething mass Behind The of humanity, slowly closing in. But Tony Shalhoub isn’t Scenes: Adrian Monk. Not any more. After eight years of Monk’s obsessive-compulsive hand-wiping, pole-touching and mystery-solving “Monk.” the often under-appreciated Final Case show that re-vitalized USA Network, made Shalhoub into an Emmy- By Joe Rhodes winning star and spawned a wave of quirkily-observant tv detective imitators, has finally come to an end. The final episode, because this is “Monk,” will put everything in its place. Before it ends – with a Randy Newman song written especially for the finale – loyal viewers will have the answers they’ve been waiting for: Who killed Monk’s wife, Trudy, the crime that sent him into a catatonic state and has hung over the series from the very first episode? Will he be reinstated as a San Francisco detective? Will he ever unbutton that top shirt button? Is that Captain Mr. Monk would not have enjoyed Stottlemeyer’s real hair? (Ok, not the this; the way things ended after the last one). 25th and final take of the final shot of the final season of the show that There will, of course, be bears his name. Adrian Monk, complications along the way, not the germophobic, claustrophobic, least of which is that Monk will be emotion-phobic, would have been told he has only three days to live. -

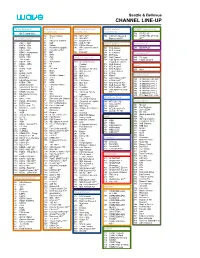

Channel Lineup

Seattle & Bellevue CHANNEL LINEUP TV On Demand* Expanded Content* Expanded Content* Digital Variety* STARZ* (continued) (continued) (continued) (continued) 1 On Demand Menu 716 STARZ HD** 50 Travel Channel 774 MTV HD** 791 Hallmark Movies & 720 STARZ Kids & Family Local Broadcast* 51 TLC 775 VH1 HD** Mysteries HD** HD** 52 Discovery Channel 777 Oxygen HD** 2 CBUT CBC 53 A&E 778 AXS TV HD** Digital Sports* MOVIEPLEX* 3 KWPX ION 54 History 779 HDNet Movies** 4 KOMO ABC 55 National Geographic 782 NBC Sports Network 501 FCS Atlantic 450 MOVIEPLEX 5 KING NBC 56 Comedy Central HD** 502 FCS Central 6 KONG Independent 57 BET 784 FXX HD** 503 FCS Pacific International* 7 KIRO CBS 58 Spike 505 ESPNews 8 KCTS PBS 59 Syfy Digital Favorites* 507 Golf Channel 335 TV Japan 9 TV Listings 60 TBS 508 CBS Sports Network 339 Filipino Channel 10 KSTW CW 62 Nickelodeon 200 American Heroes Expanded Content 11 KZJO JOEtv 63 FX Channel 511 MLB Network Here!* 12 HSN 64 E! 201 Science 513 NFL Network 65 TV Land 13 KCPQ FOX 203 Destination America 514 NFL RedZone 460 Here! 14 QVC 66 Bravo 205 BBC America 515 Tennis Channel 15 KVOS MeTV 67 TCM 206 MTV2 516 ESPNU 17 EVINE Live 68 Weather Channel 207 BET Jams 517 HRTV PayPerView* 18 KCTS Plus 69 TruTV 208 Tr3s 738 Golf Channel HD** 800 IN DEMAND HD PPV 19 Educational Access 70 GSN 209 CMT Music 743 ESPNU HD** 801 IN DEMAND PPV 1 20 KTBW TBN 71 OWN 210 BET Soul 749 NFL Network HD** 802 IN DEMAND PPV 2 21 Seattle Channel 72 Cooking Channel 211 Nick Jr. -

Jon's Mini-Codiums and More 2016

Jon's Mini-codiums and More 2016 I want to thank all of the people that ordered bulbs from me last year. This was my first time getting orders filled and it was a learning experience. After many years of drought conditions in California, it finally rained. Here in the San Francisco Bay Area, we had ample amounts of rain. My daffodils were very happy. My earliest daffodils (fall flowering species such as N. virdiflorus, N. miniatus, and N. serotinus, and fall flowering bulbocodiums bloomed.) started blooming in October 2015. More fall bloomers flowered (fall blooming cultivars, tazettas, bulbocodiums which included N. cantabricus, N. romieuxii, and Division 10 cultivars) in November and December. Many of the late winter / early spring bloomers (particularly the miniatures in Division 1, 2, 6, 9, 10, 11, and 12) grew vigorously and bloomed during the months of January through early March. The season was going to be early again. During the end of February and first week of March, I was in Arizona on vacation (went to baseball spring training), and upon our return home, it stormed and noticed that most of the miniatures that were coming Spring Serenade into bloom were ravaged by the heavy winds, rain, 5 Y-Y and pests. A few days before the Northern California Daffodil Chapter’s Murphys Show (on March 19 and 20), I was able to bring a small number of miniatures to the show. The next week, I was able to bring many of my late flowering miniatures to the Fortuna Show. Nancy and Jerry Wilson attended the show. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Mr Monk on Patrol Kindle

MR MONK ON PATROL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lee Goldberg | 278 pages | 05 Jul 2012 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780451236647 | English | New York, United States Mr. Monk Is a Mess - Wikipedia I'm a sucker for these books. Look down your nose if you must, but I like the character of Adrian Monk and I enjoy veteran TV mystery writer, Lee Goldberg's take on the continuing and ever evolving, Monkverse. Apparently this is the penultimate Mr. Monk book. Goldberg uses Monk's long-suffering assistant, Natalie as the narrator of his books. Unlike most expanded universe tie-in books, he calls back characters and events from previous books and TV episodes, weaves a decent mystery and moves the g I'm a sucker for these books. Unlike most expanded universe tie-in books, he calls back characters and events from previous books and TV episodes, weaves a decent mystery and moves the growth of the characters forward. This is probably the part I most enjoy. The book begins with a fun mystery an excerpt of which was published as a short in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, and shortlisted for an Edgar Award. Things aren't going well. Well, they are, sort of. Apparently hired in part because of a reputation as a competent, but ridiculous cop, the folks who hired him didn't count on how personable, earnest and hard-working Disher is or his uncanny ability to literally stumble into mysteries. Disher found and reported rampant, years-long corruption in the Summit city government. This lead to the resignation of the mayor and most of the town council. -

2Nd ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY FORUM 13 SEPTEMBER 2016 BERLIN AGENDA

ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY FORUM 2016 1 2ND ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY FORUM 13 SEPTEMBER 2016 BERLIN AGENDA In collaboration with #ECF16 2 ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY FORUM 2016 ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY FORUM 2016 3 TUESDAY 13 SEPTEMBER Venue: Urania ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY FORUM 09:30-09:35 Welcome & Introduction 09:35-10:05 NBC UNIVERSAL INTERNATIONAL 10:05-10:35 RED ARROW INTERNATIONAL 10:35-11:05 NORDIC WORLD 11:05-11:25 Coffee break 11:25-11:55 ZDF ENTERPRISES 11:55-12:25 ELK FORMAT 12:25-12:55 SONY PICTURES TELEVISION 12:55-13:00 End of the event 13:00 Sandwich lunch 4 ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY FORUM 2016 09:35-10:05 NBC UNIVersaL INTERNatioNAL FORMAT(S) TO BE PRESENTED • Date My Race • Hidden Singer • The Question Jury • Wedlocked OFFICE(S) NBCUniversal Central St Giles St Giles High Street London, WC2H 8NU, UK WEBSITE PRESENTED BY www.nbcuniformats.com Cecilie Olsen Director Format Sales and Production [email protected] Hannah Worrall VP Format Sales and Production [email protected] NBCUniversal Formats is the International Sales division for all formats created within the production and broadcast divisions of NBCUniversal, as well as for select third party formats. The slate encompasses Reality, Lifestyle, Entertainment and Scripted formats from NBC, Bravo, Oxygen, Syfy, E!, Carnival, Monkey Kingdom and Matchbox. NBCUniversal is one of the world’s leading media and entertainment companies in the development, production and marketing of entertainment, news and information to a global audience. ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY FORUM 2016 5 10:05-10:35 RED ARROW INTERNATIONAL FORMAT(S) TO BE PRESENTED • Look Me in the Eye • Kiss Bang Love • Real Men • The Decision • Streetlab OFFICE(S) Red Arrow International Medienallee 7 85774 Unterfoehring, Germany With offices in Munich, New PRESENTED BY York and Hong Kong, Red Arrow Nina Etspueler International has a truly global reach SVP Development & Content Strategy and distributes acclaimed, quality Creative Operations content to over 200 territories [email protected] worldwide. -

AGE Qualitative Summary

AGE Qualitative Summary Age Gender Race 16 Male White (not Hispanic) 16 Male Black or African American (not Hispanic) 17 Male Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Male White (not Hispanic) 18 Malel Blacklk or Africanf American (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 18 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Male White (not Hispanic) 19 Male Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Female Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Female Native American or Alaskan Native 19 Female White (p(not Hispanic)) 19 Male Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Native American or Alaskan Native 19 Female Other 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 20 Female White (not Hispanic) 20 Female Other 20 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 20 Male Other 20 Male Native American or Alaskan Native 21 Female Don’t want to respond 21 Female White (not Hispanic) 21 Female White (not Hispanic) 21 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 21 Female White (not -

Mkt in the News (14851)

1 613,300,000+ Online Video Subscriptions in 2018 2 Streaming Wars Cut-throat race to secure content: Disney+, Amazon Prime, Hulu, HBO Max, Apple TV, Comcast Peacock 2-front war: acquiring classics and building successful original content Sights set on Netflix massive market share — 150+ million subscribers 3 Comcast. 4 I am here because I love to give presentations. You can find me at @username Welcome Comcast Peacock. Service announced last week — set to debut April 2020 Comcast pivoting to tarket Netflix market share — 150+ million subscribers Leveraging subsidiary NBC Universal 5 Applied Marketing Mix 6 Product “I’m not sure anybody else out there can do what we can do. We expect to have great content and a great product” — Bonnie Hammer, NBCUniversal Exec. - 15,000 hours of content - Major Classics: The Office, Parks and Recreation, Brooklyn Nine Nine - Exciting New Content: Seth Meyers, Jimmy Fallon, Alec Baldwin, Battlestar Galactica Reboot 7 Place Integrated into Comcast’s existing platforms ⬡ Smart TV Integration ⬡ Xbox, PS4 Applications ⬡ Laptop, Tablet, etc. Compatibility ⬡ Mobile Devices Online Platform Designed to be Accessible from Anywhere at Any Time ⬡ Online Instantaneous Streaming ⬡ Downloads for Offline Viewing 8 Price ⬡ Free for existing Comcast TV subscribers ⬡ TBD Price for New Subscribers ⬡ (Similar competitors range from anywhere between $4.99 and $14.99) 9 Promotion - Force loyal fans of classics to the platform ($500+ million deal for The Office) - Hiring legends: Fallon, Mike Schur (produced the Office), Lorne Michaels (SNL), Alec Baldwin - Hype Build (Released April 2020) 10 SWOT. Strengths: Weaknesses: ● Soon to reacquire extremely ● Platform is Untested, Widely popular classic shows Unknown ● Network of celebrities, ● Low Current Engagement actors, and writers to build with Comcast original content ● Leverage 22+ million active Threats: pay-TV subscribers ● Intense Competition and Industry Giants Make Up Opportunities: large Portion of Market ● Target new segment: OTT ● Streaming Services are sticky 11 Netflix. -

Crossword Cryptoquip Seek and Find Jumble Movies

B8 THE NEWS-ENTERPRISE CLASSIFIEDS FRIDAY, MARCH 9, 2012 CROSSWORD FRIDAY EVENING March 9, 2012 Cable Key: E-E’town/Hardin/Vine Grove/LaRue R/B-Radcliff/Fort Knox/Muldraugh/Brandenburg E R B 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 HCEC 2 25 2 Drama Club John Hardin Prom Fashion Show Marquee Hardin County Focus-Finance Bridges Over Elizabethtown City Council Meeting WAVE 3 News at College Basketball SEC Tournament, Third Quarterfinal: Teams TBA. From New Orleans. (N) College Basketball SEC Tournament, Fourth Quarterfinal: Teams TBA. From WAVE 3 News at WAVE 3 6 3 7 (N) (CC) (Live) New Orleans. (N) (Live) 11 (N) Entertainment To- Inside Edition (N) Shark Tank Body jewelry; organic skin Primetime: What Would You Do? (N) 20/20 (N) (CC) High School Ga- (:35) Nightline (N) Jimmy Kimmel WHAS 11 4 11 night (N) (CC) care. (N) (CC) (CC) metime (CC) Live (CC) Wheel of Fortune Jeopardy! (N) Undercover Boss Oriental Trading Co. The Mentalist A terminally ill sales- Blue Bloods Erin and Danny face WLKY News at (:35) Late Show With David Letter- WLKY 5 5 5 (N) (CC) (CC) CEO Sam Taylor. (N) (CC) man is murdered. (N) (CC) each other in court. (N) (CC) 11:00PM (N) man (CC) Two and a Half The Big Bang Kitchen Nightmares “Blackberry’s; Leone’s” Improving a New Jersey eatery. WDRB News at (:45) WDRB Two and a Half 30 Rock “The Col- The Big Bang WDRB 12 9 12 Men (CC) Theory (CC) (PA) (CC) Ten (N) Sports Men (CC) lection” (CC) Theory (CC) Cold Case “November 22” Pool hus- Cold Case “The Long Blue Line” Mur- Cold Case An unkown killer commits a Cold Case The shipboard death of a Word Alive Friday Sports WBNA 6 21 10 tler’s killing examined. -

A Decade of Deceit How TV Content Ratings Have Failed Families EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Major Findings

A Decade of Deceit How TV Content Ratings Have Failed Families EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Major Findings: In its recent report to Congress on the accuracy of • Programs rated TV-PG contained on average the TV ratings and effectiveness of oversight, the 28% more violence and 43.5% more Federal Communications Commission noted that the profanity in 2017-18 than in 2007-08. system has not changed in over 20 years. • Profanity on PG-rated shows included suck/ Indeed, it has not, but content has, and the TV blow, screw, hell/damn, ass/asshole, bitch, ratings fail to reflect “content creep,” (that is, an bastard, piss, bleeped s—t, bleeped f—k. increase in offensive content in programs with The 2017-18 season added “dick” and “prick” a given rating as compared to similarly-rated to the PG-rated lexicon. programs a decade or more ago). Networks are packing substantially more profanity and violence into youth-rated shows than they did a decade ago; • Violence on PG-rated shows included use but that increase in adult-themed content has not of guns and bladed weapons, depictions affected the age-based ratings the networks apply. of fighting, blood and death and scenes We found that on shows rated TV-PG, there was a of decapitation or dismemberment; The 28% increase in violence; and a 44% increase in only form of violence unique to TV-14 rated profanity over a ten-year period. There was also a programming was depictions of torture. more than twice as much violence on shows rated TV-14 in the 2017-18 television season than in the • Programs rated TV-14 contained on average 2007-08 season, both in per-episode averages and 84% more violence per episode in 2017-18 in absolute terms.