What Is It About Judy Blume? (Under the Direction of Mary Helen Thuente.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children Entering Fourth Grade ~

New Canaan Public Schools New Canaan, Connecticut ~ Summer Reading 2018 ~ Children Entering Fourth Grade ~ 2018 Newbery Medal Winner: Hello Universe By Erin Entrada Kelly Websites for more ideas: http://booksforkidsblog.blogspot.com (A retired librarian’s excellent children’s book blog) https://www.literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/reading-lists/childrens- choices/childrens-choices-reading-list-2018.pdf Children’s Choice Awards https://www.bankstreet.edu/center-childrens-literature/childrens-book-committee/best- books-year/2018-edition/ Bank Street College Book Recommendations (All suggested titles are for reading aloud and/or reading independently.) Revised by Joanne Shulman, Language Arts Coordinator joanne,[email protected] New and Noteworthy (Reviews quoted from amazon.com) Word of Mouse by James Patterson “…a long tradition of clever mice who accomplish great things.” Fish in a Tree by Lynda Mallaly Hunt “Fans of R.J. Palacio’s Wonder will appreciate this feel-good story of friendship and unconventional smarts.”—Kirkus Reviews Secret Sisters of the Salty Seas by Lynne Rae Perkins “Perkins’ charming black-and-white illustrations are matched by gentle, evocative language that sparkles like summer sunlight on the sea…The novel’s themes of family, friendship, growing up and trying new things are a perfect fit for Perkins’ middle grade audience.”—Book Page Dash (Dogs of World War II) by Kirby Larson “Historical fiction at its best.”—School Library Journal The Penderwicks at Last by Jean Birdsall “The finale you’ve all been -

Richard Peck Lois Duncan Robert Cormier Judy Blume Gary Paulsen

Margaret A. Edwards Award winners: S.E. Hinton The publication of S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders (1967) is often heralded as the birth of modern YA. Appropri- ately, the first Margaret A. Edwards committee named Hinton the inaugu- ral recipient of the award. 1988 Sweet Valley High Pascal Scorpions Walter Dean Myers Richard Peck Robert Cormier Lois Duncan No winner in 1989, as it was originally conceived to be a The Chocolate War Cormier biennial award. Rudine Sims Bishop coins “windows, mirrors, & sliding doors.” 1990–1991 1992 Fear Street Stine M.E. Kerr Walter Dean Myers Cynthia Voigt I Hadn’t Meant to Tell You This Woodson 1993 Amazon is born, and soon emerges The Giver 1994 as a book-buying 1995 Lowry resource. Judy Blume Gary Paulsen Madeleine L’Engle The Golden Compass Pullman A boy wizard from 1996 across the pond starts to work his magic in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by 1997–1998 newbie J.K. Rowling. Anne McCaffrey Chris Crutcher The Princess Diaries In 1999 the first Cabot Michael In 2000, past L. Printz MAE winner “The thing I like best Award Walter Dean about winning the committee Myers’s Margaret A. Edwards convenes. Monster wins the first is the company in award for a book that which it puts me.” —Chris Crutcher 1999 “exemplifies literary excellence in young adult 2000 Someone Like You Heaven literature.” Stargirl Dessen Johnson Spinelli CONTINUED Robert Lipsyte Paul Zindel The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants Brashares 9/11 2001 2002 Hole in My Life Gantos Nancy Garden Ursula LeGuin Looking A banner year for LGBTQ in for Alaska YA—David Levithan’s ground- Green breaking Boy Meets Boy pub- lishes the same year Nancy Garden receives the MAE. -

Judy Blume's Printable Author

Random House Children’s Books presents . Judy Blume “When I was growing up, I dreamed about becoming a cowgirl, a detective, a spy, a great actress, or a ballerina. Not a dentist, like my father, or a homemaker, like my mother—and certainly not a writer, although I always loved to read. I didn’t know anything about writers. It never occurred to me they were regular people and that I could grow up to become one.” —Judy Blume Photo © Sigrid Estrada. Judy Blume is known and loved by millions of readers for her funny, honest, always believable stories. Among her hugely popular books are Freckle Juice, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret, and Just As Long As We’re Together. www.randomhouse.com/teachers www.randomhouse.com/teachers/themes www.randomhouse.com/librarians A Conversation with the Author When were you born? February 12, 1938. How old were you when your first book was published and which book was, it? I was 27 when I began to write seriously Where were you born? Elizabeth, New Jersey. and after two years of rejections my first book, The One in the Middle Is the Green Kangaroo, was accepted for publication. Where did you go to school? Public schools in Elizabeth, New Jersey; B.S., New York University, 1961. How long does it take you to write a book? At least a year, if there are no disruptions in my personal life and other Were you a good student? Yes, especially when the teacher professional obligations don’t get in the way. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Wednesday, March 18, 2009 2:36:33PM School: Churchland Academy Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 9318 EN Ice Is...Whee! Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 9340 EN Snow Joe Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 36573 EN Big Egg Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 99 F 9306 EN Bugs! McKissack, Patricia C. LG 0.4 0.5 69 F 86010 EN Cat Traps Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 95 F 9329 EN Oh No, Otis! Frankel, Julie LG 0.4 0.5 97 F 9333 EN Pet for Pat, A Snow, Pegeen LG 0.4 0.5 71 F 9334 EN Please, Wind? Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 55 F 9336 EN Rain! Rain! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 63 F 9338 EN Shine, Sun! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 66 F 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 171 F 9305 EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Stevens, Philippa LG 0.5 0.5 100 F 7255 EN Can You Play? Ziefert, Harriet LG 0.5 0.5 144 F 9314 EN Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol LG 0.5 0.5 58 F 9382 EN Little Runaway, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 196 F 7282 EN Lucky Bear Phillips, Joan LG 0.5 0.5 150 F 31542 EN Mine's the Best Bonsall, Crosby LG 0.5 0.5 106 F 901618 EN Night Watch (SF Edition) Fear, Sharon LG 0.5 0.5 51 F 9349 EN Whisper Is Quiet, A Lunn, Carolyn LG 0.5 0.5 63 NF 74854 EN Cooking with the Cat Worth, Bonnie LG 0.6 0.5 135 F 42150 EN Don't Cut My Hair! Wilhelm, Hans LG 0.6 0.5 74 F 9018 EN Foot Book, The Seuss, Dr. -

Superfudge by Judy Blume

Superfudge By Judy Blume Grades 4-6 Written by Nat Reed Illustrated by S&S Learning Materials About the author: Nat Reed is a retired teacher living in Southern Ontario, Canada. He has written a number of magazine articles and short stories, as well as the children’s novel Thunderbird Gold (Journey Forth Books). ISBN: 978-1-55035-936-3 Copyright 2008 All Rights Reserved * Printed in Canada Published in the U.S.A by: Published in Canada by: On The Mark Press S&S Learning Materials 3909 Witmer Road PMB 175 15 Dairy Avenue Niagara Falls, New York Napanee, Ontario 14305 K7R 1M4 www.onthemarkpress.com www.sslearning.com Permission to Reproduce Permission is granted to the individual teacher who purchases one copy of this book to reproduce the student activity material for use in his/ her classroom only. Reproduction of these materials for an entire school or for a school system, or for other colleagues or for commercial sale is strictly prohibited. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. “We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for this project.” © On The Mark Press • S&S Learning Materials 1 OTM-14273 • SSN1-273 Superfudge by Table of Contents At A GlanceTM…………………………………………………....................……………….................. 2 Overall Expectations ……..…………………………………………………...........................…......... 4 List of Skills -

Lesson Plans to Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing

Lesson Plans for Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing by JUDY BLUME Teach the Fudge series in your classroom with these integrated lesson plans and extension activities.* 978-0-14-240881-0 (PB) • $5.99 ($6.99 CAN) Ages 7 up *All plans are aligned with the Common Core Initiative. Included in this unit are: • Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing lesson plans broken down by weekly reading sessions. The book is divided into 5 reading sessions with (free) online technology integrations for most of the plans in this unit. • Writing entries to correspond with the weekly reading schedule. Teachers can use these journal ideas for students to reflect on weekly reading assignments. They can be completed in a hard copy packet or online (e.g., wiki, online course program, or other interactive online tool). • Extension activities for the four other books in the Fudge series: Otherwise known as Sheila the Great, Superfudge, Fudge-a-mania, and Double Fudge • An interview with Judy Blume! • Recommendations for additional Web 2.0 programs Lesson Ideas for Lesson Ideas for Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing Week 1: Chapters 1 and 2 Week 2: Chapters 3 and 4 1. Character Catcher: Split students into two teams. Have each team brainstorm words that 1. Infomercial Mania: Fudge refuses to eat, which worries his mother, who feels he is not getting describe characteristics (e.g., traits, motivations, or feelings) of Peter, Fudge, Mother, Father, the proper nutrition. Have students research the food pyramid. Then have students select an Mr. -

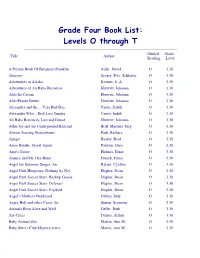

Grade Four Book List: Levels O Through T

Grade Four Book List: Levels O through T Guided Grade Title Author Reading Level A Picture Book Of Benjamin Franklin Adler, David O 3.30 Abiyoyo Seeger, Pete Schlastic O 3.30 Adventures in Alaska Kramer, S. A. O 3.30 Adventures of Ali Baba Bernstein Hurwitz, Johanna O 3.30 Aldo Ice Cream Hurwitz, Johanna O 3.30 Aldo Peanut Butter Hurwitz, Johanna O 3.30 Alexander and the ... Very Bad Day Viorst, Judith O 3.30 Alexander Who... Rich Last Sunday Viorst, Judith O 3.30 Ali Baba Bernstein, Lost and Found Hurwitz, Johanna O 3.30 Allen Jay and the Underground Railroad Brill, Marlene Targ O 3.30 Almost Starring Skinnybones Park, Barbara O 3.30 Amigo Baylor, Byrd O 3.30 Amos Binder, Secret Agent Paulsen, Gary O 3.30 Amy's Goose Holmes, Efner O 3.30 Anancy and Mr. Dry-Bone French, Fiona O 3.30 Angel for Solomon Singer, An Rylant, Cynthia O 3.30 Angel Park Hoopstars: Nothing by Net Hugher, Dean O 3.30 Angel Park Soccer Stars: Backup Goalie Hugher, Dean O 3.30 Angel Park Soccer Stars: Defense! Hugher, Dean O 3.30 Angel Park Soccer Stars: Psyched Hugher, Dean O 3.30 Angel's Mother's Boyfriend Delton, Judy O 3.30 Angry Bull and other Cases, the Simon, Seymour O 3.30 Animals Born Alive and Well Heller, Ruth O 3.30 Ant Cities Dorros, Arthur O 3.30 Baby Animal Zoo Martin, Ann M. O 3.30 Baby Sitters Club Mystery series Martin, Ann M. O 3.30 Back Home Pinkey, Gloria Jean O 3.30 Back Yard Angel Delton, Judy O 3.30 Baseball Challenge and Other Cases, the Simon, Seymour O 3.30 Baseball Fever Hurwitz, Johanna O 3.30 Baseball Megastars Weber, Bruce O 3.30 Baseball Saved Us Mochizuki, Ken O 3.30 Baseball's Best:Five True Stories Gutelle, Andrew O 3.30 Bats Gibbons, Gail O 3.30 Bats Holmes, Kevin J. -

Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing.Pdf

My biggest problem is my brother, Farley Drexel Hatcher. Everybody calls him Fudge. I feel sorry for him if he’s going to grow up with a name like Fudge, but I don’t say a word. It’s none of my business. Fudge is always in my way. He messes up everything he sees. And when he gets mad he throws himself flat on the floor and he screams. And he kicks. And he bangs his fists. The only time I really like him is when he’s sleeping. He sucks four fingers on his left hand and makes a slurping noise. When Fudge saw Dribble he said, “Ohhhhh . see!” And I said, “That’s my turtle, get it? Mine! You don’t touch him.” Fudge said, “No touch.” Then he laughed like crazy. BOOKS BY JUDY BLUME The Pain and the Great One Soupy Saturdays with the Pain and the Great One Cool Zone with the Pain and the Great One Going, Going, Gone! with the Pain and the Great One Friend or Fiend? with the Pain and the Great One The One in the Middle Is the Green Kangaroo Freckle Juice THE FUDGE BOOKS Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing Otherwise Known as Sheila the Great Superfudge Fudge-a-Mania Double Fudge Blubber Iggie’s House Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret It’s Not the End of the World Then Again, Maybe I Won’t Deenie Just as Long as We’re Together Here’s to You, Rachel Robinson Tiger Eyes Forever Letters to Judy Places I Never Meant to Be: Original Stories by Censored Writers (edited by Judy Blume) PUFFIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Young Readers Group, 345 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. -

Talking with Judy Blume by Judy Freeman

Talking With Judy Blume By Judy Freeman he believable voices of Judy Contribution to American Letters (in to be cyclical. (Or maybe it’s publish- Blume’s characters—such as 2004, Blume became the first chil- ing that tends to be cyclical.) In the T the troublemaking Fudge from dren’s author to receive this honor). 1970s series books were out. Fantasy Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing and Read on to discover what else this was out. Rhyming picture books were freckle-less Andrew from Freckle well-loved writer has to say! out. Kids need choices. There are Juice—have charmed readers since always some who want to read about Blume published her first book, Why do you think that, after 35 real life. I write for those readers. The One in the Middle Is the Green years, your books are so popular? Kangaroo, in 1969. In fact, Blume’s JUDY BLUME: I’ve no idea. I’d guess What children’s writers have first fans are all grown up and sharing it’s that young readers continue to influenced you? her stories with a new generation. identify with my characters. Some JB: When I began to write I’d go to In Instructor’s recent reader survey, things never change. the public library and carry home teachers named her one of their top armloads of books. I laughed so hard 10 favorite children’s authors. Are kids’ interests today different I fell off the sofa reading Beverly That’s why we wanted to talk to from those of kids in the 1970s? Cleary. -

Dec 2005 NEWSLETTER

THE VISION OF THE FRIENDS IS AN OUTSTANDING KEY WEST LIBRARY WITH STRONG COMMUNITY SUPPORT JANUARY 2016 PRESIDENT’S NOTES BOARD MEMBERS Happy 2016! So many books, so little time! Do you have a plan for Kathleen Bratton your reading this year? As a lawyer, I used to read so much technical mate- President rial that I limited my recreational reading almost exclusively to fiction. Marsha Williams Several years ago, however, after I stopped practicing, I began to feel very Vice President guilty about all the unread non-fiction books sitting on my shelves. (As Marny Heinen you may have guessed, I am a compulsive book buyer. I admit it. When I Secretary work at the Friends’ book sales, I only permit myself to bring $5 so I will Tom Clements not go too crazy with purchases.) Treasurer I decided to develop a plan for reading that would include a variety of non-fiction in addition to my usual fiction. The first year of my plan I came up with 19 cat- Joyce Drake egories. I listed them in a notebook, leaving spaces between each for what I call for Jennifer Franke “mysteries” but in fact includes every variety of crime-related literature—hard-boiled, proce- Judith Gaddis durals, cozies, thrillers, suspense, classics—everything. By 2015, I had expanded to 36 Arlo Haskell categories! I have included some classic literature as well. I have been making my way Mark Hedden through the Brontes and should finish up with Villette this year. I am also reading Trollope Roberta Isleib in chronological order; in 2016 I expect to reread Framley Parsonage. -

Book Title Author Reading Level Approx. Grade Level

Approx. Reading Book Title Author Grade Level Level Anno's Counting Book Anno, Mitsumasa A 0.25 Count and See Hoban, Tana A 0.25 Dig, Dig Wood, Leslie A 0.25 Do You Want To Be My Friend? Carle, Eric A 0.25 Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Growing Colors McMillan, Bruce A 0.25 In My Garden McLean, Moria A 0.25 Look What I Can Do Aruego, Jose A 0.25 What Do Insects Do? Canizares, S.& Chanko,P A 0.25 What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith, Brain B 0.5 Getting There Young B 0.5 Hats Around the World Charlesworth, Liza B 0.5 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, Eric B 0.5 Have you seen my Duckling? Tafuri, Nancy/Greenwillow B 0.5 Here's Skipper Salem, Llynn & Stewart,J B 0.5 How Many Fish? Cohen, Caron Lee B 0.5 I Can Write, Can You? Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 Look, Look, Look Hoban, Tana B 0.5 Mommy, Where are You? Ziefert & Boon B 0.5 Runaway Monkey Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 So Can I Facklam, Margery B 0.5 Sunburn Prokopchak, Ann B 0.5 Two Points Kennedy,J. & Eaton,A B 0.5 Who Lives in a Tree? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Who Lives in the Arctic? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Apple Bird Wildsmith, Brain C 1 Apples Williams, Deborah C 1 Bears Kalman, Bobbie C 1 Big Long Animal Song Artwell, Mike C 1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Martin, Bill C 1 Found online, 7/20/2012, http://home.comcast.net/~ngiansante/ Approx. -

Title Author Gr Elementary Approved Literature List by Title

Elementary Approved Literature List by Title Title Author Gr 10 for Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 3 100 Book Race: Hog Wild in the Reading Room, The Giff, Patricia Reilly 1 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 4 12 Ways to Get to 11 Merriam, Eve 2 26 Fairmount Avenue dePaola, Tomie 2 3D Modeling Zizka, Theo 3 3D Printing O'Neill, Ternece 3 4 Valentines In A Rainstorm Bond, Felicia 1 5th of March Rinaldi, Ann 5 6 Titles: Eagles, Bees and Wasps, Alligators and Crocodiles, Giraffes,Morgan, SallySharks, Tortoises and Turtles1 A Likely Place Fox, Paula 4 A Long Walk to Water Park, Linda Sue 5 A Nightmare in History: The Holocaust 1933-1945 Chaikin, Miriam 5 A Rock is Lively Aston, Diana Hutts 1 A, My Name Is Alice Bayer, Jane 2 Abandoned Puppy Costello, Emily 3 ABC Bunny, The Gag, Wanda 1 Abe Lincoln Goes to Washington Harness, Cheryl 2 Abe Lincoln's Hat Brenner, Martha 2 Abel's Island Steig, William 3 Abigail Adams, Girl of Colonial Days Wagoner, Jean Brown 2 Abraham Lincoln Cashore, Kristen 2 Abraham Lincoln, Lawyer, Leader, Legend Fontes, Justine & Ron 2 Abraham Lincoln: Great Man, Great Words Cashore, Kristen 5 Updated November 20, 2019 *previously approved at higher grade level 1 Elementary Approved Literature List by Title Title Author Gr Abraham Lincoln: Our 16th President Luciano, Barbara L. 4 Absolutely Lucy Cooper, Ilene 2 Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4 Accident, The Carrick, Carol 3 Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 5 Across the Stream Ginsburg, Mirra 1 Across the Wild River Gutman, Bill 4 Addie Across the Prairie Lawler, Laurie 4 Adrian Simcox