Jus Algoritmi: How the National Security Agency Remade Citizenship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Xkeyscore, and Can It 'Eavesdrop on Everyone, Everywhere'? (+Video) - Csmonitor.Com

8/3/13 What is XKeyscore, and can it 'eavesdrop on everyone, everywhere'? (+video) - CSMonitor.com The Christian Science Monitor CSMonitor.com What is XKeyscore, and can it 'eavesdrop on everyone, everywhere'? (+video) XKeyscore is apparently a tool the NSA uses to sift through massive amounts of data. Critics say it allows the NSA to dip into people's 'most private thoughts' – a claim key lawmakers reject. This photo shows an aerial view of the NSA's Utah Data Center in Bluffdale, Utah. The long, squat buildings span 1.5 million square feet, and are filled with super powered computers designed to store massive amounts of information gathered secretly from phone calls and emails. (Rick Bowmer/AP/File) By Mark Clayton, Staff writer / August 1, 2013 at 9:38 pm EDT Topsecret documents leaked to The Guardian newspaper have set off a new round of debate over National Security Agency surveillance of electronic communications, with some cyber experts saying the trove reveals new and more dangerous means of digital snooping, while some members of Congress suggested that interpretation was incorrect. The NSA's collection of "metadata" – basic call logs of phone numbers, time of the call, and duration of calls – is now wellknown, with the Senate holding a hearing on the subject this week. But the tools discussed in the new Guardian documents apparently go beyond mere collection, allowing the agency to sift through the www.csmonitor.com/layout/set/print/USA/2013/0801/What-is-XKeyscore-and-can-it-eavesdrop-on-everyone-everywhere-video 1/4 8/3/13 What is XKeyscore, and can it 'eavesdrop on everyone, everywhere'? (+video) - CSMonitor.com haystack of digital global communications to find the needle of terrorist activity. -

The Right to Privacy and the Future of Mass Surveillance’

‘The Right to Privacy and the Future of Mass Surveillance’ ABSTRACT This article considers the feasibility of the adoption by the Council of Europe Member States of a multilateral binding treaty, called the Intelligence Codex (the Codex), aimed at regulating the working methods of state intelligence agencies. The Codex is the result of deep concerns about mass surveillance practices conducted by the United States’ National Security Agency (NSA) and the United Kingdom Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). The article explores the reasons for such a treaty. To that end, it identifies the discriminatory nature of the United States’ and the United Kingdom’s domestic legislation, pursuant to which foreign cyber surveillance programmes are operated, which reinforces the need to broaden the scope of extraterritorial application of the human rights treaties. Furthermore, it demonstrates that the US and UK foreign mass surveillance se practices interferes with the right to privacy of communications and cannot be justified under Article 17 ICCPR and Article 8 ECHR. As mass surveillance seems set to continue unabated, the article supports the calls from the Council of Europe to ban cyber espionage and mass untargeted cyber surveillance. The response to the proposal of a legally binding Intelligence Codexhard law solution to mass surveillance problem from the 47 Council of Europe governments has been so far muted, however a soft law option may be a viable way forward. Key Words: privacy, cyber surveillance, non-discrimination, Intelligence Codex, soft law. Introduction Peacetime espionage is by no means a new phenomenon in international relations.1 It has always been a prevalent method of gathering intelligence from afar, including through electronic means.2 However, foreign cyber surveillance on the scale revealed by Edward Snowden performed by the United States National Security Agency (NSA), the United Kingdom Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) and their Five Eyes partners3 1 Geoffrey B. -

Advocating for Basic Constitutional Search Protections to Apply to Cell Phones from Eavesdropping and Tracking by Government and Corporate Entities

University of Central Florida STARS HIM 1990-2015 2013 Brave New World Reloaded: Advocating for Basic Constitutional Search Protections to Apply to Cell Phones from Eavesdropping and Tracking by Government and Corporate Entities Mark Berrios-Ayala University of Central Florida Part of the Legal Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIM 1990-2015 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Berrios-Ayala, Mark, "Brave New World Reloaded: Advocating for Basic Constitutional Search Protections to Apply to Cell Phones from Eavesdropping and Tracking by Government and Corporate Entities" (2013). HIM 1990-2015. 1519. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/1519 BRAVE NEW WORLD RELOADED: ADVOCATING FOR BASIC CONSTITUTIONAL SEARCH PROTECTIONS TO APPLY TO CELL PHONES FROM EAVESDROPPING AND TRACKING BY THE GOVERNMENT AND CORPORATE ENTITIES by MARK KENNETH BERRIOS-AYALA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Legal Studies in the College of Health and Public Affairs and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2013 Thesis Chair: Dr. Abby Milon ABSTRACT Imagine a world where someone’s personal information is constantly compromised, where federal government entities AKA Big Brother always knows what anyone is Googling, who an individual is texting, and their emoticons on Twitter. -

A Failure of Intelligence: the Echelon Interception System & the Fundamental Right to Privacy in Europe

Pace International Law Review Volume 14 Issue 2 Fall 2002 Article 7 September 2002 Post-Sept. 11th International Surveillance Activity - A Failure of Intelligence: The Echelon Interception System & the Fundamental Right to Privacy in Europe Kevin J. Lawner Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr Recommended Citation Kevin J. Lawner, Post-Sept. 11th International Surveillance Activity - A Failure of Intelligence: The Echelon Interception System & the Fundamental Right to Privacy in Europe, 14 Pace Int'l L. Rev. 435 (2002) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr/vol14/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace International Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POST-SEPT. 11TH INTERNATIONAL SURVEILLANCE ACTIVITY - A FAILURE OF INTELLIGENCE: THE ECHELON INTERCEPTION SYSTEM & THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT TO PRIVACY IN EUROPE Kevin J. Lawner* I. Introduction ....................................... 436 II. Communications Intelligence & the United Kingdom - United States Security Agreement ..... 443 A. September 11th - A Failure of Intelligence .... 446 B. The Three Warning Flags ..................... 449 III. The Echelon Interception System .................. 452 A. The Menwith Hill and Bad Aibling Interception Stations .......................... 452 B. Echelon: The Abuse of Power .................. 454 IV. Anti-Terror Measures in the Wake of September 11th ............................................... 456 V. Surveillance Activity and the Fundamental Right to Privacy in Europe .............................. 460 A. The United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union... 464 B. -

Case3:08-Cv-04373-JSW Document174-2 Filed01/10/14 Page1 of 7 Exhibit 2

Case3:08-cv-04373-JSW Document174-2 Filed01/10/14 Page1 of 7 Exhibit 2 Exhibit 2 1/9/14 Case3:08-cv-04373-JSWNew Details S Document174-2how Broader NSA Surveil la n Filed01/10/14ce Reach - WSJ.com Page2 of 7 Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit www.djreprints.com See a sample reprint in PDF Order a reprint of this article now format. U.S. NEWS New Details Show Broader NSA Surveillance Reach Programs Cover 75% of Nation's Traffic, Can Snare Emails By SIOBHAN GORMAN and JENNIFER VALENTINO-DEVRIES Updated Aug. 20, 2013 11:31 p.m. ET WASHINGTON—The National Security Agency—which possesses only limited legal authority to spy on U.S. citizens—has built a surveillance network that covers more Americans' Internet communications than officials have publicly disclosed, current and former officials say. The system has the capacity to reach roughly 75% of all U.S. Internet traffic in the hunt for foreign intelligence, including a wide array of communications by foreigners and Americans. In some cases, it retains the written content of emails sent between citizens within the U.S. and also filters domestic phone calls made with Internet technology, these people say. The NSA's filtering, carried out with telecom companies, is designed to look for communications that either originate or end abroad, or are entirely foreign but happen to be passing through the U.S. -

Bulk Powers in the Investigatory Powers Bill: the Question of Trust Remains Unanswered

Bulk Powers In The Investigatory Powers Bill: The Question Of Trust Remains Unanswered BULK POWERS IN THE INVESTIGATORY POWERS BILL: The Question Of Trust Remains Unanswered September 2016 1/10 Bulk Powers In The Investigatory Powers Bill: The Question Of Trust Remains Unanswered Introduction We are on the brink of introducing the most pervasive and intrusive surveillance legislation of any democratic country in the world. The Investigatory Powers Bill sought to answer important questions about the place that modern and highly intrusive surveillance capabilities have in a democratic society, questions that were raised by the Edward Snowden disclosures in 2013 and subsequent reports produced by David Anderson QC, the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) and the Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) in 2015. But just a matter of weeks before the new law is enacted, significant questions of trust remain unanswered. This paper highlights some of the key flaws Privacy International sees in the current incarnation of the Investigatory Powers Bill, and urges the House of Lords to put the brakes on the bulk powers, about which many important questions remain unanswered. In this paper we set out how: • the Bill fails to provide sufficient clarity, which was promised at the outset of the legislative process, to alleviate confusion around the UK’s surveillance laws; • the Bill has not advanced transparency to the degree needed, still leaving most of the public in the dark about the extent of the surveillance powers; • significant questions remain about the Bill’s safeguards and oversight regime; and • major questions also remain regarding the bulk powers, even in light of David Anderson QC’s recent report. -

Summary of U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Law, Practice, Remedies, and Oversight

___________________________ SUMMARY OF U.S. FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE LAW, PRACTICE, REMEDIES, AND OVERSIGHT ASHLEY GORSKI AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION AUGUST 30, 2018 _________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS QUALIFICATIONS AS AN EXPERT ............................................................................................. iii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 I. U.S. Surveillance Law and Practice ................................................................................... 2 A. Legal Framework ......................................................................................................... 3 1. Presidential Power to Conduct Foreign Intelligence Surveillance ....................... 3 2. The Expansion of U.S. Government Surveillance .................................................. 4 B. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 ..................................................... 5 1. Traditional FISA: Individual Orders ..................................................................... 6 2. Bulk Searches Under Traditional FISA ................................................................. 7 C. Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act ........................................... 8 D. How The U.S. Government Uses Section 702 in Practice ......................................... 12 1. Data Collection: PRISM and Upstream Surveillance ........................................ -

Mass Surveillance

Mass Surveillance Mass Surveillance What are the risks for the citizens and the opportunities for the European Information Society? What are the possible mitigation strategies? Part 1 - Risks and opportunities raised by the current generation of network services and applications Study IP/G/STOA/FWC-2013-1/LOT 9/C5/SC1 January 2015 PE 527.409 STOA - Science and Technology Options Assessment The STOA project “Mass Surveillance Part 1 – Risks, Opportunities and Mitigation Strategies” was carried out by TECNALIA Research and Investigation in Spain. AUTHORS Arkaitz Gamino Garcia Concepción Cortes Velasco Eider Iturbe Zamalloa Erkuden Rios Velasco Iñaki Eguía Elejabarrieta Javier Herrera Lotero Jason Mansell (Linguistic Review) José Javier Larrañeta Ibañez Stefan Schuster (Editor) The authors acknowledge and would like to thank the following experts for their contributions to this report: Prof. Nigel Smart, University of Bristol; Matteo E. Bonfanti PhD, Research Fellow in International Law and Security, Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna Pisa; Prof. Fred Piper, University of London; Caspar Bowden, independent privacy researcher; Maria Pilar Torres Bruna, Head of Cybersecurity, Everis Aerospace, Defense and Security; Prof. Kenny Paterson, University of London; Agustín Martin and Luis Hernández Encinas, Tenured Scientists, Department of Information Processing and Cryptography (Cryptology and Information Security Group), CSIC; Alessandro Zanasi, Zanasi & Partners; Fernando Acero, Expert on Open Source Software; Luigi Coppolino,Università degli Studi di Napoli; Marcello Antonucci, EZNESS srl; Rachel Oldroyd, Managing Editor of The Bureau of Investigative Journalism; Peter Kruse, Founder of CSIS Security Group A/S; Ryan Gallagher, investigative Reporter of The Intercept; Capitán Alberto Redondo, Guardia Civil; Prof. Bart Preneel, KU Leuven; Raoul Chiesa, Security Brokers SCpA, CyberDefcon Ltd.; Prof. -

Meeting the Privacy Movement

-----BEGIN PGP MESSAGE----- Charset: utf-8 Version: GnuPG v2 hQIMA5xNM/DISSENT7ieVABAQ//YbpD8i8BFVKQfbMy I3z8R8k/ez3oexH+sGE+tPRIVACYMOVEMENTRvU+lSB MY5dvAkknydTOF7xIEnODLSq42eKbrCToDMboT7puJSlWr W Meeting the Privacy Movement d 76hzgkusgTrdDSXure5U9841B64SwBRzzkkpLra4FjR / D z e F Dissent in the Digital Age 0 M 0 0 m BIPhO84h4cCOUNTERREVOLUTION0xm17idq3cF5zS2 GXACTIVISTSXvV3GEsyU6sFmeFXNcZLP7My40pNc SOCIALMOVEMENTgQbplhvjN8i7cEpAI4tFQUPN0dtFmCu h8ZOhP9B4h5Y681c5jr8fHzGNYRDC5IZCDH5uEZtoEBD8 FHUMANRIGHTSwxZvWEJ16pgOghWYoclPDimFCuIC 7K0dxiQrN93RgXi/OEnfPpR5nRU/Qv7PROTESTaV0scT nwuDpMiAGdO/byfCx6SYiSURVEILLANCEFnE+wGGpKA0rh C9Qtag+2qEpzFKU7vGt4TtJAsRc+5VhNSAq8OMmi8 n+i4W54wyKEPtkGREENWALDk41TM9DN6ES7sHtA OfzszqKTgB9y10Bu+yUYNO2d4XY66/ETgjGX3a7OY/vbIh Ynl+MIZd3ak5PRIVACYbNQICGtZAjPOITRAS6E ID4HpDIGITALAGEBhcsAd2PWKKgHARRISON4hN4mo7 LIlcr0t/U27W7ITTIEpVKrt4ieeesji0KOxWFneFpHpnVcK t4wVxfenshwUpTlP4jWE9vaa/52y0xibz6az8M62rD9F/ XLigGR1jBBJdgKSba38zNLUq9GcP6YInk5YSfgBVsvTzb VhZQ7kUU0IRyHdEDgII4hUyD8BERLINmdo/9bO/4s El249ZOAyOWrWHISTLEBLOWINGrQDriYnDcvfIGBL 0q1hORVro0EBDqlPA6MOHchfN+ck74AY8HACKTIVISMy 8PZJLCBIjAJEdJv88UCZoljx/6BrG+nelwt3gCBx4dTg XqYzvOSNOWDENTEahLZtbpAnrot5APPELBAUMzAW Qn6tpHj1NSrAseJ/+qNC74QuXYXrPh9ClrNYN6DNJGQ +u8ma3xfeE+psaiZvYsCRYPTOGRAPHYwkZFimy R9bjwhRq35Fe1wXEU4PNhzO5muDUsiDwDIGITAL A Loes Derks van de Ven X o J 9 1 H 0 w J e E n 2 3 S i k k 3 W Z 5 s XEGHpGBXz3njK/Gq+JYRPB+8D5xV8wI7lXQoBKDGAs -----END PGP MESSAGE----- Meeting the Privacy Movement Dissent in the Digital Age by Loes Derks van de Ven A thesis presented to the -

We Only Spy on Foreigners": the Myth of a Universal Right to Privacy and the Practice of Foreign Mass Surveillance

Chicago Journal of International Law Volume 18 Number 2 Article 3 1-1-2018 "We Only Spy on Foreigners": The Myth of a Universal Right to Privacy and the Practice of Foreign Mass Surveillance Asaf Lubin Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cjil Recommended Citation Lubin, Asaf (2018) ""We Only Spy on Foreigners": The Myth of a Universal Right to Privacy and the Practice of Foreign Mass Surveillance," Chicago Journal of International Law: Vol. 18: No. 2, Article 3. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cjil/vol18/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “We Only Spy on Foreigners”: The Myth of a Universal Right to Privacy and the Practice of Foreign Mass Surveillance Asaf Lubin Abstract The digital age brought with it a new epoch in global political life, one neatly coined by Professor Philip Howard as the “pax technica.” In this new world order, government and industry are “tightly bound” in technological and security arrangements that serve to push forward an information and cyber revolution of unparalleled magnitude. While the rise of information technologies tells a miraculous story of triumph over the physical constraints that once shackled mankind, these very technologies are also the cause of grave concern. Intelligence agencies have been recently involved in the exercise of global indiscriminate surveillance, which purports to go beyond their limited territorial jurisdiction and sweep in “the telephone, internet, and location records of whole populations.” Today’s political leaders and corporate elites are increasingly engaged in these kinds of programs of bulk interception, collection, mining, analysis, dissemination, and exploitation of foreign communications data that are easily susceptible to gross abuse and impropriety. -

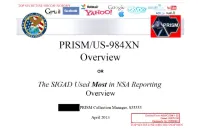

PRISM/US-984XN Overview

TOP SFCRF.T//SI//ORCON//NOFORX a msn Hotmail Go« „ paltalk™n- Youffl facebook Gr-iai! AOL b mail & PRISM/US-984XN Overview OR The SIGAD Used Most in NSA Reporting Overview PRISM Collection Manager, S35333 Derived From: NSA/CSSM 1-52 April 20L-3 Dated: 20070108 Declassify On: 20360901 TOP SECRET//SI// ORCON//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI//ORCON//NOEÛEK ® msnV Hotmail ^ paltalk.com Youi Google Ccnmj<K8t« Be>cnö Wxd6 facebook / ^ AU • GM i! AOL mail ty GOOglC ( TS//SI//NF) Introduction ILS. as World's Telecommunications Backbone Much of the world's communications flow through the U.S. • A target's phone call, e-mail or chat will take the cheapest path, not the physically most direct path - you can't always predict the path. • Your target's communications could easily be flowing into and through the U.S. International Internet Regional Bandwidth Capacity in 2011 Source: Telegeographv Research TOP SECRET//SI// ORCON//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI//ORCON//NOEQBN Hotmail msn Google ^iïftvgm paltalk™m YouSM) facebook Gm i ¡1 ^ ^ M V^fc i v w*jr ComnuMcatiw Bemm ^mmtmm fcyGooglc AOL & mail  xr^ (TS//SI//NF) FAA702 Operations U « '«PRISM/ -A Two Types of Collection 7 T vv Upstream •Collection of ;ommujai£ations on fiber You Should Use Both PRISM • Collection directly from the servers of these U.S. Service Providers: Microsoft, Yahoo, Google Facebook, PalTalk, AOL, Skype, YouTube Apple. TOP SECRET//SI//ORCON//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI//ORCON//NOEÛEK Hotmail ® MM msn Google paltalk.com YOUE f^AVi r/irmiVAlfCcmmjotal«f Rhnnl'MirBe>coo WxdS6 GM i! facebook • ty Google AOL & mail Jk (TS//SI//NF) FAA702 Operations V Lfte 5o/7?: PRISM vs. -

SURVEILLE NSA Paper Based on D2.8 Clean JA V5

FP7 – SEC- 2011-284725 SURVEILLE Surveillance: Ethical issues, legal limitations, and efficiency Collaborative Project This project has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no. 284725 SURVEILLE Paper on Mass Surveillance by the National Security Agency (NSA) of the United States of America Extract from SURVEILLE Deliverable D2.8: Update of D2.7 on the basis of input of other partners. Assessment of surveillance technologies and techniques applied in a terrorism prevention scenario. Due date of deliverable: 31.07.2014 Actual submission date: 29.05.2014 Start date of project: 1.2.2012 Duration: 39 months SURVEILLE WorK PacKage number and lead: WP02 Prof. Tom Sorell Author: Michelle Cayford (TU Delft) SURVEILLE: Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Seventh Framework Programme Dissemination Level PU Public X PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) Commission Services) Executive summary • SURVEILLE deliverable D2.8 continues the approach pioneered in SURVEILLE deliverable D2.6 for combining technical, legal and ethical assessments for the use of surveillance technology in realistic serious crime scenarios. The new scenario considered is terrorism prevention by means of Internet monitoring, emulating what is known about signals intelligence agencies’ methods of electronic mass surveillance. The technologies featured and assessed are: the use of a cable splitter off a fiber optic backbone; the use of ‘Phantom Viewer’ software; the use of social networking analysis and the use of ‘Finspy’ equipment installed on targeted computers.