Stephen King and the Construction of Authorship As a Mass-Mediated Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cumulative Michigan Notable Books List

Author(s) Title Publisher Genre Year Abbott, Jim Imperfect Ballantine Books Memoir 2013 Abood, Maureen Rose Water and Orange Blossoms: Fresh & Classic Recipes from My Lebenese Kitchen Running Press Non-fiction 2016 Ahmed, Saladin Abbott Boom Studios Fiction 2019 Airgood, Ellen South of Superior Riverhead Books Fiction 2012 Albom, Mitch Have a Little Faith: A True Story Hyperion Non-fiction 2010 Alexander, Jeff The Muskegon: The Majesty and Tragedy of Michigan's Rarest River Michigan State University Press Non-fiction 2007 Alexander, Jeff Pandora's Locks: The Opening of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway Michigan State University Press Non-fiction 2010 Amick, Steve The Lake, the River & the Other Lake: A Novel Pantheon Books Fiction 2006 Amick, Steve Nothing But a Smile: A Novel Pantheon Books Fiction 2010 Anderson, Godfrey J. A Michigan Polar Bear Confronts the Bolsheviks: A War Memoir: the 337th Field Hospital in Northern Russia William B. Eerdmans' Publishing Co. Memoir 2011 Anderson, William M. The Detroit Tigers: A Pictorial Celebration of the Greatest Players and Moments in Tigers' History Dimond Communications Photo-essay 1992 Andrews, Nancy Detroit Free Press Time Frames: Our Lives in 2001, our City at 300, Our Legacy in Pictures Detroit Free Press Photography 2003 Appleford, Annie M is for Mitten: A Michigan Alphabet Book Sleeping Bear Press Children's 2000 Armour, David 100 Years at Mackinac: A Centennial History of the Mackinac Island State Park Commission, 1895-1995 Mackinac Island State Historic Parks History 1996 Arnold, Amy & Conway, Brian Michigan Modern: Designed that Shaped America Gibbs Smith Non-fiction 2017 Arnow, Harriette Louisa Simpson Between the Flowers Michigan State University Press Fiction 2000 Bureau of History, Michigan Historical Commission, Michigan Department of Ashlee, Laura R. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Town of Calumet 2020 Roadwork Rehabilitation Bid Proposal – Road Segments

Town of Calumet 2020 Roadwork Rehabilitation Bid Proposal – Road Segments Bid Date: Monday June 1, 2020 Bid Time: 6:00 P.M. Town of Calumet Town Hall W2104 County Highway HH Malone, WI 53049 Table of Contents Page(s) Description 2 Specifications and General Provisions 3-5 General Specifications 6 Asphalt Concrete 7 Basis of Payment by Ton 8-14 Bid Form (by Contractor) 15 Bid Proposal (by Contractor) 16-17 Bid Proposal Certification (by Contractor) 18 Notice of Award (by Owner) 19 Acceptance of Notice of Award (by Owner) 20-21 Agreement (by Owner and Contractor) 22 Blank 23 Change Order Form (by Owner and Contractor) 5/18/2020 5:50 PM 1 of 23 File 3 - Bid Spec-Roads- Final Town of Calumet 2020 Roadwork Rehabilitation Bid Proposal – Road Segments Town of Calumet 2020 Road Segments Specifications and Special Provisions Bid Proposals will be received until 6:00 p.m. central daylight time June 1, 2020. Bids to be opened on June 1, 2020 at 6:00 p.m. at the town board special meeting at the town hall, located at the corner of Town Hall Road and County Highway HH Malone, WI 53049. Bid Proposals will be available by contacting Don Breth or Jodie Goebel. Any contact regarding this proposal should be made to: Don Breth, Chairperson – (847) 867-6306 Jodie Goebel, Clerk - (920) 795-4040 Mailing Address: PO Box 92 Malone, WI 53049 Bids will be submitted on the bidding documents provided by the Town of Calumet with the exception that a computer-generated schedule of prices may be attached to this proposal if it is within reasonable conformity to the bidding proposal provided. -

Traci & Kimberly, to the Children's Library To

July, August, September 2008 Volume 4 Number 3 515 North Fifth Street * Bismarck, ND 58501 * www.bismarcklibrary.org * 701-355-1480 Open Mon.– Thurs. 9 a.m.—9 p.m. , Fri.—Sat. 9 a.m.—6 p.m., Sun. 1—6 p.m. Welcome, Traci & Kimberly, to the Children’s Library ur newly hired Head of Children’s Services is Traci Juhala, a Bismarck na- Lobby Displays OOO July tive. She received her Bachelors in Music and Norwegian from UND; her Masters Resurrection Collection by Research in Scandinavian Studies from the University of Edinburgh, Scotland; from Magic Photo and her Masters in Library and Information Science from the University of Illinois. Aug., Sept., Oct.: She has worked in several library environments, but she much prefers public librar- Dolls of the East: ies, and in particular, children’s services. She is looking forward to all of the fun Japan and China and wonderful perks of being a children’s librarian, including seeing all the new children’s fiction, helping young people with science project ideas, playing with Workshops puppets, and , especially, hearing laugh- Ancestry Workshops ter and happy voices every day. Traci Tues. July 8, 2-3:30 will be deeply involved in the Children’s Thurs. July 31, 6:30-8 Renovation Project. In her spare time, Thurs. Aug 21, 6:30-8 Traci enjoys being involved with the mu- Tues. Sept. 30, 2-3:30 sical community by playing cello with the Missouri Valley Chamber Orchestra Classes Offered by and the Bismarck-Mandan Symphony. the Library She takes an active role in music ministry Classes on Internet I, at her church. -

Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 414 606 CS 216 137 AUTHOR Power, Brenda Miller, Ed.; Wilhelm, Jeffrey D., Ed.; Chandler, Kelly, Ed. TITLE Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-3905-1 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 246p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 39051-0015: $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Censorship; Critical Thinking; *Fiction; Literature Appreciation; *Popular Culture; Public Schools; Reader Response; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Programs; Recreational Reading; Secondary Education; *Student Participation IDENTIFIERS *Contemporary Literature; Horror Fiction; *King (Stephen); Literary Canon; Response to Literature; Trade Books ABSTRACT This collection of essays grew out of the "Reading Stephen King Conference" held at the University of Mainin 1996. Stephen King's books have become a lightning rod for the tensions around issues of including "mass market" popular literature in middle and 1.i.gh school English classes and of who chooses what students read. King's fi'tion is among the most popular of "pop" literature, and among the most controversial. These essays spotlight the ways in which King's work intersects with the themes of the literary canon and its construction and maintenance, censorship in public schools, and the need for adolescent readers to be able to choose books in school reading programs. The essays and their authors are: (1) "Reading Stephen King: An Ethnography of an Event" (Brenda Miller Power); (2) "I Want to Be Typhoid Stevie" (Stephen King); (3) "King and Controversy in Classrooms: A Conversation between Teachers and Students" (Kelly Chandler and others); (4) "Of Cornflakes, Hot Dogs, Cabbages, and King" (Jeffrey D. -

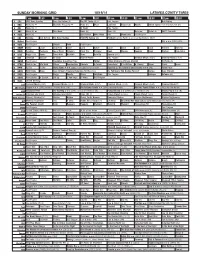

Sunday Morning Grid 10/19/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/19/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Meet LazyTown Poppy Cat Noodle Action Sports From Brooklyn, N.Y. (N) 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. ABC7 Presents 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Carolina Panthers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program I.Q. ››› (1994) (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Home Alone 4 ›› (2002, Comedia) French Stewart. -

Lisey's Story

LISEY’S STORY ABOUT THE BOOK IN BRIEF: Lisey Landon is the woman behind bestselling novelist Scott Landon - not that the world knows it. For twenty- five years she has been the light to his dark, and as his wife, she was the only one who saw the truth behind the public face of the famous author - that he was a haunted man whose bestselling novels were based on a terrifying reality. Now Scott is dead, Lisey wants to concentrate on the memories of the man she loved. But the fans and academics have a different idea, determined to pull his dark secrets into the light. IN DETAIL: King has written about writers several times before, but this is the first time he has switched focus to the writer’s wife. This allows him to explore career-long interests in a fascinating new way. As with Jack Torrance in The Shining, it’s not entirely clear whether writing is a ‘healthy’ process for Scott Landon, but it’s undoubtedly a necessary one, allowing him to deal with his disturbing life and unusual way of looking at the world. Scott Landon is a successful author (he’s won the Pulitzer and the National Book Award), and as in Misery he has problems with obsessive fans. This causes trouble in his life (when a fan shoots him), and after his death, as an academic is so desperate to get his hands on Landon’s unpublished work that he takes to threatening Lisey. But Lisey can take of herself. The novel goes on to explores Lisey’s life after Scott’s death, but it is also details the twenty-five years of their relationship, and the family secrets that have bonded the couple together. -

Four Past Midnight by Stephen King #W9TS60ZEJD2 #Free Read Online

Four Past Midnight Stephen King Click here if your download doesn"t start automatically Four Past Midnight Stephen King Four Past Midnight Stephen King The Bram Stoker Prize-winner for Best Fiction Collection—four chilling novellas from Stephen King that will “grab you and not let go” (The Washington Post). “Stephen King is a master storyteller, and you will never forget these stories,” raves the Seattle Times about Four Past Midnight. This collection, guaranteed to keep readers awake long after bedtime, features an introduction and prefatory notes to each novella by the author. One Past Midnight: “The Langoliers” takes a red-eye flight from LA to Boston into a most unfriendly sky. Only eleven passengers survive, but landing in an eerily empty world makes them wish they hadn’t. Something’s waiting for them, you see. Two Past Midnight: “Secret Window, Secret Garden” enters the suddenly strange life of writer Mort Rainey, recently divorced, depressed, and alone on the shore of Tashmore Lake. Alone, that is, until a figure named John Shooter arrives, pointing an accusing finger. Three Past Midnight: “The Library Policeman” is set in Junction City, Iowa, an unlikely place for evil to be hiding. But for small businessman Sam Peebles, who thinks he may be losing his mind, another enemy is hiding there as well—the truth. If he can find it in time, he might stand a chance. Four Past Midnight: “The Sun Dog,” a menacing black dog, appears in every Polaroid picture that fifteen- year-old Kevin Delevan takes with his new camera, beckoning him to the supernatural. -

100M Dash (5A Girls) All Times Are FAT, Except

100m Dash (5A Girls) All times are FAT, except 2 0 2 1 R A N K I N G S A L L - T I M E T O P - 1 0 P E R F O R M A N C E S 1 12 Nerissa Thompson 12.35 North Salem 1 Margaret Johnson-Bailes 11.30a Churchill 1968 2 12 Emily Stefan 12.37 West Albany 2 Kellie Schueler 11.74a Summit 2009 3 9 Kensey Gault 12.45 Ridgeview 3 Jestena Mattson 11.86a Hood River Valley 2015 4 12 Cyan Kelso-Reynolds 12.45 Springfield 4 LeReina Woods 11.90a Corvallis 1989 5 10 Madelynn Fuentes 12.78 Crook County 5 Nyema Sims 11.95a Jefferson 2006 6 10 Jordan Koskondy 12.82 North Salem 6 Freda Walker 12.04c Jefferson 1978 7 11 Sydney Soskis 12.85 Corvallis 7 Maya Hopwood 12.05a Bend 2018 8 12 Savannah Moore 12.89 St Helens 8 Lanette Byrd 12.14c Jefferson 1984 9 11 Makenna Maldonado 13.03 Eagle Point Julie Hardin 12.14c Churchill 1983 10 10 Breanna Raven 13.04 Thurston Denise Carter 12.14c Corvallis 1979 11 9 Alice Davidson 13.05 Scappoose Nancy Sim 12.14c Corvallis 1979 12 12 Jada Foster 13.05 Crescent Valley Lorin Barnes 12.14c Marshall 1978 13 11 Tori Houg 13.06 Willamette Wind-Aided 14 9 Jasmine McIntosh 13.08 La Salle Prep Kellie Schueler 11.68aw Summit 2009 15 12 Emily Adams 13.09 The Dalles Maya Hopwood 12.03aw Bend 2016 16 9 Alyse Fountain 13.12 Lebanon 17 11 Monica Kloess 13.14 West Albany C L A S S R E C O R D S 18 12 Molly Jenne 13.14 La Salle Prep 9th Kellie Schueler 12.12a Summit 2007 19 9 Ava Marshall 13.16 South Albany 10th Kellie Schueler 12.01a Summit 2008 20 11 Mariana Lomonaco 13.19 Crescent Valley 11th Margaret Johnson-Bailes 11.30a Churchill 1968 -

2006 NGA Annual Meeting

1 1 NATIONAL GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION 2 OPENING PLENARY SESSION 3 Saturday, August 5, 2006 4 Governor Mike Huckabee, Arkansas--Chairman 5 Governor Janet Napolitano, Arizona--Vice Chair 6 TRANSFORMING THE U.S. HEALTH CARE SYSTEM 7 Guest: 8 The Honorable Tommy C. Thompson, former Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and former Governor 9 of Wisconsin 10 HEALTHY AMERICA: A VIEW HEALTH FROM THE INDUSTRY 11 Facilitator: 12 Charles Bierbauer, Dean, College of Mass Communications and Information Studies, University of South Carolina 13 Guests: 14 Donald R. Knauss, President, Coca-Cola North America 15 Steven S. Reinemund, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, 16 PepsiCo, Inc. 17 Stephen W. Sanger, Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer, General Mills, Inc. 18 19 DISTINGUISHED SERVICE AWARDS 20 RECOGNITION OF 15-YEAR CORPORATE FELLOW 21 RECOGNITION OF OUTGOING GOVERNORS 22 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE BUSINESS 23 24 REPORTED BY: Roxanne M. Easterwood, RPR 25 A. WILLIAM ROBERTS, JR., & ASSOCIATES (800) 743-DEPO 2 1 APPEARANCE OF GOVERNORS 2 Governor Easley, North Carolina 3 Governor Douglas, Vermont 4 Governor Blanco, Louisiana 5 Governor Riley, Alabama 6 Governor Blunt, Missouri 7 Governor Pawlenty, Minnesota 8 Governor Owens, Colorado 9 Governor Gregoire, Washington 10 Governor Henry, Oklahoma 11 Governor Acevedo Vila, Puerto Rico 12 Governor Turnbull, Virgin Islands 13 Governor Risch, Idaho 14 Governor Schweitzer, Montana 15 Governor Manchin, West Virginia 16 Governor Vilsack, Iowa 17 Governor Fletcher, Kentucky 18 Governor Pataki, New York 19 Governor Lynch, New Hampshire 20 Governor Kaine, Virginia 21 Governor Sanford, South Carolina 22 Governor Romney, Massachusetts 23 Governor Minner, Delaware 24 25 A. -

May 2017 New Releases

MAY 2017 NEW RELEASES GRAPHIC NOVELS • MANGA • SCI-FI/ FANTASY • GAMES VORACIOUS : FEEDING TIME Hunting dinosaurs and secretly serving them at his restaurant, Fork & Fossil, has helped Chef ISBN-13: 978-1-63229-235-3 Nate Willner become a big success. But just when he’s starting to make something of his life, Price: $17.99 ($23.99 CAN) Publisher: Action Lab he discovers that his hunting trips with Captain Jim are actually taking place in an alternate Entertainment reality – an Earth where dinosaurs evolve into Saurians, a technologically advanced race that Writer: Markisan Naso rules the far future! Some of these Saurians have mysteriously started vanishing from Artist: Jason Muhr Cretaceous City and the local authorities are hell-bent on finding who’s responsible. Nate’s Page Count: 160 world is about to collide with something much, much bigger than any dinosaur he’s ever Format: Softcover, Full Color Recommended Age: Mature roasted. Readers (ages 16 and up) Genre: Science Fiction Collecting VORACIOUS: Feeding Time #1-5, this second volume of the critically acclaimed Ship Date: 6/6/2017 series serves up a colorful bowl of characters and a platter full of sci-fi adventure, mystery and heart! SELECTED PREVIOUS VOLUMES: • Voracious: Diners, Dinosaurs & Dives (ISBN-13 978-1-63229-165-3, $14.99) PROVIDENCE ACT 1 FINAL PRINTING HC Due to overwhelming demand, we offer one final printing of the Providence Act 1 Hardcover! ISBN-13: 978-1-59291-291-9 Alan Moore’s quintessential horror series has set the standard for a terrifying reinvention of Price: $19.99 ($26.50 CAN) Publisher: Avatar Press the works of H.P. -

Interview with Van Jensen, Author of Casino Royale (Dynamite, 2018, Pp

Interview with Van Jensen, author of Casino Royale (Dynamite, 2018, pp. 160) ELLEN J. STOCKSTILL In March 2018, Dynamite Entertainment published a graphic novel adaptation of Ian Fleming’s first !ames "ond novel, Casino Royale# Dynamite secured the li$ cense to adapt the novel from the Fleming estate back in 201& and slated 'riter (an !ensen and artist Dennis )alero to produce the adaptation# In the follo'ing intervie', !ensen describes the process of adapting Fleming’s novel, some of the challenges of 'or%ing 'ith an iconic character li%e !ames "ond, Fleming’s 'rit$ ing style, "ond s current and historical relevance, and the 'ays in 'hich Flem$ ing’s legacy lives on in different mediums. Ellen Stockstill: )an you explore the relevance of this particular medium to the "ond franchise? ,hy this form, and 'hy this %ind of adaptation no' in this par$ ticular period of "ond s cultural lifespan+ Van Jensen: -ltimately, the .uestion of /,hy a graphic novel+0 is one that 'as considered and ans'ered by the Fleming 1ublishing Library, as it 'as their deci$ sion to pursue the publishing partnership 'ith Dynamite Entertainment# I do Ellen J. Stockstill is Assistant Professor of English at Penn State Harrisburg where she teaches courses on British literature and critical theory. Her scholarship fo- cuses on Victorian literature and culture. She is co-author of A Research Guide to Gothic Literature in English (Row- man & Littlefield, 2018), and she has published essays in Vol. 1, Issue 2 · Spring 2018 Public Domain Review, Nineteenth-Century Prose, Victorian ISSN 2514-2178 Medicine and Popular Culture (Routledge), and The Moral DOI: 10.24877/jbs.33 Panics of Sexuality (Palgrave).