Introduction Kenneth Mtata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Competing Views of Original Sin and Associated Arguments and Meanings

CHAPTER TWO COMPETING VIEWS OF ORIGINAL SIN AND ASSOCIATED ARGUMENTS AND MEANINGS The dispute over the definition of original sin, or more precisely, Matthias Flacius Illyricus’s1 controversial explanation of this doctrine, originated at the University of Jena in 1560 among the highest levels of the Lutheran academic world. It did not enter the territory of Mansfeld until a decade later. There it first claimed the attention of those clerics who operated in intellectual circles that went beyond the territory’s borders. But divisions within this ecclesiastical leadership soon spread throughout the territory’s entire pastorate. It may seem strange to begin a discussion of lay religiosity with elite theologians debating abstract points of doctrine in ivory towers. But in order to understand why the laity of Mansfeld became deeply involved in the controversy, it is important to start at the beginning with the central intellectual premise, and work outward to the various meanings and connotations it came to encompass. Only then can the laity’s association with one side or the other begin to make sense. The assumption here is that a purely intellectual weighing of the validity of the two definitions of original sin was not the only aspect of the debate 1 Matthias Flacius Illyricus (1520–1575) was born in Croatia, but studied in Venice, Basel, and Tübingen, before matriculating in Wittenberg in 1541. He eventu- ally became a professor of Hebrew there, where he was influenced by both Luther and Melanchthon, the former particularly with regard to pastoral care, the latter with regard to theology. After Emperor Charles V’s defeat of the Lutheran princes in the Schmalkald War (1547), as Melanchthon was urging a conciliatory policy, Flacius took up the banner of complete resistance. -

Melanchthon Versus Luther: the Contemporary Struggle

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 44, Numbers 2-3 --- - - - JULY 1980 Can the Lutheran Confessions Have Any Meaning 450 Years Later?.................... Robert D. Preus 104 Augustana VII and the Eclipse of Ecumenism ....................................... Sieg bert W. Becker 108 Melancht hon versus Luther: The Contemporary Struggle ......................... Bengt Hagglund 123 In-. Response to Bengt Hagglund: The importance of Epistemology for Luther's and Melanchthon's Theology .............. Wilbert H. Rosin 134 Did Luther and Melanchthon Agree on the Real Presence?.. ....................................... David P. Scaer 14 1 Luther and Melanchthon in America ................................................ C. George Fry 148 Luther's Contribution to the Augsburg Confession .............................................. Eugene F. Klug 155 Fanaticism as a Theological Category in the Lutheran Confessions ............................... Paul L. Maier 173 Homiletical Studies 182 Melanchthon versus Luther: the Contemporary Struggle Bengt Hagglund Luther and Melanchthon in Modern Research In many churches in Scandinavia or in Germany one will find two oil paintings of the same size and datingfrom the same time, representing Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon, the two prime reformers of the Church. From the point of view of modern research it may seem strange that Melanchthon is placed on the same level as Luther, side by side with him, equal in importance and equally worth remembering as he. Their common achieve- ment was, above all, the renewal of the preaching of the Gospel, and therefore it is deserving t hat their portraits often are placed in the neighborhood of the pulpit. Such pairs of pictures were typical of the nineteenth-century view of Melanchthon and Luther as harmonious co-workers in the Reformation. These pic- tures were widely displayed not only in the churches, but also in many private homes in areas where the Reformation tradition was strong. -

![[Formula of Concord]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9966/formula-of-concord-1099966.webp)

[Formula of Concord]

[Formula of Concord] Editors‘ Introduction to the Formula of Concord Every movement has a period in which its adherents attempt to sort out and organize the fundamental principles on which the founder or founders of the movement had based its new paradigm and proposal for public life. This was true of the Lutheran Reformation. In the late 1520s one of Luther‘s early students, John Agricola, challenged first the conception of God‘s law expressed by Luther‘s close associate and colleague, Philip Melanchthon, and, a decade later, Luther‘s own doctrine of the law. This began the disputes over the proper interpretation of Luther‘s doctrinal legacy. In the 1530s and 1540s Melanchthon and a former Wittenberg colleague, Nicholas von Amsdorf, privately disagreed on the role of good works in salvation, the bondage or freedom of the human will in relationship to God‘s grace, the relationship of the Lutheran reform to the papacy, its relationship to government, and the real presence of Christ‘s body and blood in the Lord‘s Supper. The contention between the two foreshadowed a series of disputes that divided the followers of Luther and Melanchthon in the period after Luther‘s death, in which political developments in the empire fashioned an arena for these disputes. In the months after Luther‘s death on 18 February 1546, Emperor Charles V finally was able to marshal forces to attempt the imposition of his will on his defiant Lutheran subjects and to execute the Edict of Worms of 1521, which had outlawed Luther and his followers. -

Martin Chemnitz on the Doctrine of Justification

Martin Chemnitz on the Doctrine of Justification [Presented at the Reformation Lectures, Bethany Lutheran College and Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary, October 30, 1985, Lecture II] By Dr. Jacob A. 0. Preus 1. In 1537 at Wittenberg Luther presided over a Disputatio held in connection with the academic promotion of two candidates, Palladius and Tilemann, in which he discussed the passage in Rom. 3:28, “We believe that a man is justified by faith apart from the works of the law.” Luther, in his prefatory remarks, said, “The article of justification is the master and prince, the lord and ruler and judge of all areas of doctrine. It preserves and governs the entire teaching of the church and directs our conscience before God. Without this article the world is in total death and darkness, for there is no error so small, so insignificant and isolated that it does not completely please the mind of man and mislead us, if we are cut off from thinking and meditating on this article. Therefore, because the world is so obtuse and insensitive, it is necessary to deal with this doctrine constantly and have the greatest understanding of it. Especially if we wish to advise the churches, we will fear no evil, if we give the greatest labor and diligence in teaching particularly this article. For when the mind has been strengthened and confirmed in this sure knowledge, then it can stand firm in all things. Therefore, this is not some small or unimportant matter, particularly for those who wish to stand on the battle line and contend against the devil, sin, and death and teach the churches.” 2. -

John Blahoslav, "Father and Charioteer of the Lord's People in the Unitas Fratrum"

John Blahoslav, "Father and Charioteer of the Lord's People in the Unitas Fratrum" MILOS STRUPL Brief was the span of life which the Lord had allotted to Brother John Blahoslav. When he, "of the topmost four", one of the bishops of his communion, died on the twenty-fourth day of November 1571, while on a visit near Moravsky Krumlov, he had not yet reached his forty- ninth year. "All too soon, according to our judgment", sighed Lawrence Orlik, Blahoslav's faithful co-worker, as he was recording the death of his superior in the Necrology of the Unitas Fratrum, "it pleased the Lord to take him away; he himself knows for what reason. Mysterious divine judgments!" 1 And yet, its brevity notwithstanding, it had been a full life, crowded with the most diversified activities in the service of his beloved Unitas. For Blahoslav was indeed - quoting once more from Orlik's Necrology - "a great and outstanding man, whose fame, having been carried far and wide, excelled among other nations, a great and precious jewel of the Unitas".2 In this glowing appraisal Orlik did not remain alone. Others have voiced similar opinions. To mention just one, a modern historian, Vaclav Novotny, referred to Blahoslav as "one of the noblest spirits of his time, one of the most learned of his contemporaries, and therefore one of the most celebrated sons of his nation".3 No one will seriously question that in the history of the Unitas Fratrum Blahoslav holds a truly pivotal position. His importance must be judged in comparison with that of Brother Lucas of Prague, "the second founder of the Unitas", and that of John Amos Comenius, its last great spiritual leader and a man of undeniable international stature. -

The Formula of Concord As a Model for Discourse in the Church

21st Conference of the International Lutheran Council Berlin, Germany August 27 – September 2, 2005 The Formula of Concord as a Model for Discourse in the Church Robert Kolb The appellation „Formula of Concord“ has designated the last of the symbolic or confessional writings of the Lutheran church almost from the time of its composition. This document was indeed a formulation aimed at bringing harmony to strife-ridden churches in the search for a proper expression of the faith that Luther had proclaimed and his colleagues and followers had confessed as a liberating message for both church and society fifty years earlier. This document is a formula, a written document that gives not even the slightest hint that it should be conveyed to human ears instead of human eyes. The Augsburg Confession had been written to be read: to the emperor, to the estates of the German nation, to the waiting crowds outside the hall of the diet in Augsburg. The Apology of the Augsburg Confession, it is quite clear from recent research,1 followed the oral form of judicial argument as Melanchthon presented his case for the Lutheran confession to a mythically yet neutral emperor; the Apology was created at the yet not carefully defined border between oral and written cultures. The Large Catechism reads like the sermons from which it was composed, and the Small Catechism reminds every reader that it was written to be recited and repeated aloud. The Formula of Concord as a „Binding Summary“ of Christian Teaching In contrast, the „Formula of Concord“ is written for readers, a carefully- crafted formulation for the theologians and educated lay people of German Lutheran churches to ponder and study. -

Lutheran Confessions Bible Study

A Brief Introduction to the Lutheran Confessions A Bible Study Course for Adults by Robert J. Koester Student Lessons • Lesson One—The Three Ecumenical Creeds: “The Ancient Church’s Confession” • Lesson Two—The Small and Large Catechisms: “The People’s Confession” • Lesson Three—The Augsburg Confession and the Apology: “The Princes’ Confession” • Lesson Four—The Smalcald Articles: “Luther’s Confession” • Lesson Five—The Formula of Concord, Part One: “The Theologians’ Confession” Scripture is taken from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved. All quotations from the confessions, where noted as Kolb and Wengert, are from The Book of Concord edited by Robert Kolb and Timothy Wengert, © 2000 Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. Used by permission of Augsburg Fortress Publishers. All rights reserved. Northwestern Publishing House 1250 N. 113th St., Milwaukee, WI 53226-3284 www.nph.net © 2009 by Northwestern Publishing House Published 2009 Lesson One The Three Ecumenical Creeds: “The Ancient Church’s Confession” Introduction: What Are the Lutheran Confessions? Anyone who has attended the installation of a pastor or teacher in a confessional Lutheran church has heard the officiant ask the person being installed several questions. Among them are “Do you confess the Holy Scriptures to be the inspired Word of God?” and “Do you hold to the confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran church and believe they are a correct exposition of Scripture?” Then the officiant reads off the list of the Lutheran Confessions. Unless you have received the formal training of a pastor or teacher, you may be left scratching your head. -

The Use of the Church Fathers in the Formula of Concord

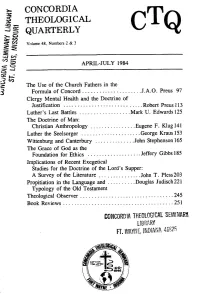

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 48. Numbers 2 & 3 APRIL-JULY 1984 The Use of the Church Fathers in the Formula of Concord .....................J.A.O. Preus 97 Clergy Mental Health and the Doctrine of Justification ............................Robert Preus 1 13 Luther's Last Battles ..................Mark U. Edwards 125 The Doctrine of Man: Christian Anthropology ................Eugene F. Klug 14 1 Luther the Seelsorger .....................George Kraus 153 Wittenburg and Canterbury ............. .John Stephenson 165 The Grace of God as the Foundation for Ethics ....... ............Jeffery Gibbs 185 Implications of Recent Exegetical Studies for the Doctrine of the Lord's Supper: A Survey of the Literature ... ............John T. Pless 203 Propitiation in the Language and ..........Douglas Judisch 22 1 Typology of the Old Testament Theological Observer .................................245 Book Reviews .......................................251 The Use of the Church Fathers in the Formula of Concord J.A.O. Preus The use of the church fathers in the Formula of Concord reveals the attitude of the writers of the Formula to Scripture and to tradition. The citation of the church fathers by these theologians was not intended to override the great principle of Lutheranism, which was so succinctly stated in the Smalcalci Ar- ticles, "The Word of God shall establish articles of faith, and no one else, not even an angel" (11, 2.15). The writers of the Formula subscribed wholeheartedly to Luther's dictum. But it is also true that the writers of the Formula, as well as the writers of all the other Lutheran Confessions, that is, Luther and Melanchthon, did not look upon themselves as operating in a theological vacuum. -

Flacius' Struggle for the Freedom of the Church

S. Jambrek: Flacius’ Struggle for the Freedom of the Church Flacius’ Struggle for the Freedom of the Church Stanko Jambrek Bible Institute, Zagreb, Croatia [email protected] UDK:261.7:262 Review paper Received: July, 2012. Accepted: September, 2012. Summary Matthias Flacius Illyricus is reputed to have been one of the most influential Croatian humanists and theologians of the 16th century. Through his numer- ous works, he gave an efficient theological, philosophical, historical, linguistic and educational contribution to European cultural history. Besides a concise review of Flacius’ life, the article discusses the truth as Flacius’ starting point in his arguments and in life in general. Then it focuses on Flacius’ spiritual/ theological struggle for the freedom of the church which contributed greatly to the defeat of the pro-Catholic politics of Emperor Charles V and the survival of the Lutheran tradition of the Reformation in the German countries. Key words: Augsburg Interim, Bible, Gospel, truth, Luther, theology, Flacius Introduction According to the notion of Radovan Ivančević (2004, 9), Matthias Flacius led only a meager group of Croatian thinkers who are now globally recognized as compelling contributors to the European cultural and scientific history of the 16th century. Ivančević has effectively and characteristically modified the expression “Stop Rojters” into the expression “Stop Flacius” because when Flacius published secret church and state documents accompanied by his direct and undisguised comments, he discovered the concealed purposes and goals of the enemies of the truth. After Luther’s death (1546), severe political, church-political, theological and cultural battles were waged in the German lands, and Flacius contributed to each one of them considerably. -

'Matthias Flacius and the Survival of Luther's Reform'

H-German Rein on Olson, 'Matthias Flacius and the survival of Luther's reform' Review published on Tuesday, July 1, 2003 Oliver K. Olson. Matthias Flacius and the survival of Luther's reform. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2002. 432 S. + 72 Abb. EUR 99.00 (gebunden), ISBN 978-3-447-04404-2. Reviewed by Nathan Rein (Department of Philosophy and Religion, Ursinus College) Published on H-German (July, 2003) The German Reformation's South European Hero The German Reformation's South European Hero For the past two decades or so, interest in the German Reformation has increasingly focused on the phenomenon known as "confessionalization," which began anywhere between 1530 and 1555. After the Wildwuchs of the 1520s, when the Reformation movement spread rapidly and uncontrollably, confessionalization represents the institutionalization and crystallization of the previous decades' changes. Against the exuberance and intensity of the early Reform movement, the later developments suggest a different flavor: consolidation of authority, creation of an orthodox consensus, the "settling down" of the Reform. Matthias Flacius Illyricus (1520-1575), born the same year that Martin Luther published his three great Reformation treatises, belongs to this period. Illyricus has always been a troubling figure in the landscape of the late Reformation. As a professor at Wittenberg and Jena as well as a staggeringly prolific religious writer, he loomed over many of the doctrinal controversies that plagued the confessionalization period. Yet he never succeeded in fitting comfortably into a party, institution or school of thought. He was a Croatian. And according to Olson's account, the Protestant Germans among whom he worked--and who saw the Reformation as their movement--never let him forget his origins. -

Distinguishing Law and Gospel: a Functional View James Arne Nestingen

Distinguishing Law and Gospel: A Functional View James Arne Nestingen As both Luther and Walther insisted, the proper distinction of Law and Gospel is fundamental to sound preaching. The contemporary experience of the church bears out the truth of their arguments. When Law and Gospel are improperly distinguished, both are undermined. Separated from the Law, the Gospel gets absorbed into an ideology of tolerance in which indiscriminateness is equated with grace. Separated from the Gospel, the Law becomes an insatiable demand hammering away at the conscience until it destroys a person. When Law and Gospel are properly distinguished, however, both are established. The Law can be set forth in its full-scale demand, so that it lights the way to order and through the work of the Spirit drives us to Christ. The Gospel can be declared in all of its purity, so that forgiveness of sins and deliverance from the powers of death and the devil are bestowed in the presence of our crucified and risen Lord. Yet even within the Reformation itself, the church experienced difficulty with the distinction. This occurred most publicly in the 1540s, when Melanchthon proposed to include the preaching of repentance within the realm of the Gospel. Flacius, ever vigilant, challenged quickly, arguing that this in fact transforms the Gospel from a gift of grace into another command. During the ensuing controversy, the issue shifted back and forth between the question of the relationship of Gospel with re pentance and the manner of definition. Pastors also experience difficulty with the distinction. It happens both ways, with Law and Gospel. -

The Formula of Concord (1576-80) and Satis Est

The Formula of Concord (1576-80) and Satis Est Nicholas Hoppmann Nicholas Hoppmann is a senior history major at Eastern Illinois University. He wrote this paper for Dr. David Smith’s undergraduate Western Civilization since the Reformation survey class in the spring of 2000. rticle VII of the Augsburg Confession (1530) has long guided Lutherans in their attempts to bring together the denominations. It defines the one holy catholic church, of which all true Christians are members, doctrinally, stating that the church is a gathering where “the Gospel is taught purely and the sacraments are administered rightly.” Article AVII’s satis est states, “it is sufficient for the true unity of the Christian church that the gospel be preached in conformity with a pure understanding of it and that the sacraments be administered in accordance with the divine word.” And yet, the Lutheran Confessions of the sixteenth century condemned the teachings of other Reformation churches as well as the Papacy. Lutherans hope that by participating in discussions with the descendants of these sixteenth- century churches, doctrinal agreements will be reached that will render the Lutheran anathemas obsolete. This process has raised many important questions about the satis est. One of the most important questions is: how do the many other doctrines presented in the Lutheran Confessions relate to the doctrine of satis est? Recently the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA, the largest Lutheran Church body in the United States), which subscribes to the Lutheran Confessions (contained in The Book of Concord), has declared that several Calvinist Churches are orthodox.