Application for Inclusion of Fludrocortisone Tablets in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children (July 2008)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Progesterone: an Enigmatic Ligand for the Mineralocorticoid Receptor

Progesterone: An Enigmatic Ligand for the Mineralocorticoid Receptor Michael E. Baker1 Yoshinao Katsu2 1Division of Nephrology-Hypertension Department of Medicine, 0735 University of California, San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, CA 92093-0735 2Graduate School of Life Science Hokkaido University Sapporo, Japan Correspondence to: M. E. Baker; E-mail: [email protected] Y. Katsu; E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The progesterone receptor (PR) mediates progesterone regulation of female reproductive physiology, as well as gene transcription in non-reproductive tissues, such as brain, bone, lung and vasculature, in both women and men. An unusual property of progesterone is its high affinity for the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), which regulates electrolyte transport in the kidney in humans and other terrestrial vertebrates. In humans, rats, alligators and frogs, progesterone antagonizes activation of the MR by aldosterone, the physiological mineralocorticoid in terrestrial vertebrates. In contrast, in elephant shark, ray-finned fishes and chickens, progesterone activates the MR. Interestingly, cartilaginous fishes and ray-finned fishes do not synthesize aldosterone, raising the question of which steroid(s) activate the MR in cartilaginous fishes and ray-finned fishes. The simpler synthesis of progesterone, compared to cortisol and other corticosteroids, makes progesterone a candidate physiological activator of the MR in elephant sharks and ray-finned fishes. Elephant shark and ray-finned fish MRs are expressed in diverse tissues, including heart, brain and lung, as well as, ovary and testis, two reproductive tissues that are targets for progesterone, which together suggests a multi-faceted physiological role for progesterone activation of the MR in elephant shark and ray-finned fish. -

Adrenal Disorders

Adrenal Disorders Dual-release Hydrocortisone in Addison’s Disease— A Review of the Literature Roberta Giordano, MD,1 Federica Guaraldi, MD,2 Rita Berardelli, MD,2 Ioannis Karamouzis, MD,2 Valentina D’Angelo, MD,2 Clizia Zichi, MD,2 Silvia Grottoli, MD,2 Ezio Ghigo, PhD2 and Emanuela Arvat, PhD3 1. Department of Clinical and Biological Sciences; 2. Division of Endocrinology, Diabetology and Metabolism, Department of Medical Sciences; 3. Division of Oncological Endocrinology, Department of Medical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin, Italy Abstract In patients with adrenal insufficiency, glucocorticoids (GCs) are insufficiently secreted and GC replacement is essential for health and, indeed, life. Despite GC-replacement therapy, patients with adrenal insufficiency have a greater cardiovascular risk than the general population, and suffer from impaired health-related quality of life. Although the aim of the replacement GC therapy is to reproduce as much as possible the physiologic pattern of cortisol secretion by the normal adrenal gland, the pharmacokinetics of available oral immediate-release hydrocortisone or cortisone make it impossible to fully mimic the cortisol rhythm. Therefore, there is an unmet clinical need for the development of novel pharmaceutical preparations of hydrocortisone, in order to guarantee a more physiologic serum cortisol concentration time-profile, and to improve the long-term outcome in patients under GC substitution therapy. Keywords Addison’s disease, glucocorticoids, hydrocortisone, Plenadren®, limits, advantages Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Received: June 28, 2013 Accepted: August 9, 2013 Citation: US Endocrinology 2013;9(2):177–80 DOI: 10.17925/USE.2013.09.02.177 Correspondence: Roberta Giordano, MD, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetology and Metabolism, Department of Medical Sciences, Azienda Ospedaliera Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino, C so Dogliotti 14, 10126 Turin, Italy. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0221245 A1 Kunin (43) Pub

US 2010O221245A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0221245 A1 Kunin (43) Pub. Date: Sep. 2, 2010 (54) TOPICAL SKIN CARE COMPOSITION Publication Classification (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventor: Audrey Kunin, Mission Hills, KS A 6LX 39/395 (2006.01) (US) A6II 3L/235 (2006.01) A638/16 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: (52) U.S. Cl. ......................... 424/133.1: 514/533: 514/12 HUSCH BLACKWELL SANDERS LLP (57) ABSTRACT 4801 Main Street, Suite 1000 - KANSAS CITY, MO 64112 (US) The present invention is directed to a topical skin care com position. The composition has the unique ability to treat acne without drying out the user's skin. In particular, the compo (21) Appl. No.: 12/395,251 sition includes a base, an antibacterial agent, at least one anti-inflammatory agent, and at least one antioxidant. The (22) Filed: Feb. 27, 2009 antibacterial agent may be benzoyl peroxide. US 2010/0221 245 A1 Sep. 2, 2010 TOPCAL SKIN CARE COMPOSITION stay of acne treatment since the 1950s. Skin irritation is the most common side effect of benzoyl peroxide and other anti BACKGROUND OF THE INVENTION biotic usage. Some treatments can be severe and can leave the 0001. The present invention generally relates to composi user's skin excessively dry. Excessive use of some acne prod tions and methods for producing topical skin care. Acne Vul ucts may cause redness, dryness of the face, and can actually garis, or acne, is a common skin disease that is prevalent in lead to more acne. Therefore, it would be beneficial to provide teenagers and young adults. -

Lymphoid Organs of Neonatal and Adult Mice Preferentially Produce Active Glucocorticoids from Metabolites, Not Precursors ⇑ Matthew D

Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 57 (2016) 271–281 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Brain, Behavior, and Immunity journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ybrbi Full-length Article Lymphoid organs of neonatal and adult mice preferentially produce active glucocorticoids from metabolites, not precursors ⇑ Matthew D. Taves a,b, , Adam W. Plumb c, Anastasia M. Korol a, Jessica Grace Van Der Gugten d, Daniel T. Holmes d, Ninan Abraham b,c,1, Kiran K. Soma a,b,e,1 a Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, 2136 West Mall, Vancouver V6T 1Z4, Canada b Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, 4200-6270 University Blvd, Vancouver V6T 1Z4, Canada c Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of British Columbia, 1365-2350 Health Sciences Mall, Vancouver V6T 1Z3, Canada d Department of Laboratory Medicine, St Paul’s Hospital, 1081 Burrard St, Vancouver, BC V6Z 1Y6, Canada e Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health, University of British Columbia, 2215 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3, Canada article info abstract Article history: Glucocorticoids (GCs) are circulating adrenal steroid hormones that coordinate physiology, especially the Received 4 March 2016 counter-regulatory response to stressors. While systemic GCs are often considered immunosuppressive, Received in revised form 22 April 2016 GCs in the thymus play a critical role in antigen-specific immunity by ensuring the selection of competent Accepted 7 May 2016 T cells. Elevated thymus-specific GC levels are thought to occur by local synthesis, but the mechanism of Available online 7 May 2016 such tissue-specific GC production remains unknown. Here, we found metyrapone-blockable GC produc- tion in neonatal and adult bone marrow, spleen, and thymus of C57BL/6 mice. -

Mineralocorticoid Receptor Mutations

234 1 M-C ZENNARO and MR mutations 234:1 T93–T106 Thematic Review F FERNANDES-ROSA 30 YEARS OF THE MINERALOCORTICOID RECEPTOR Mineralocorticoid receptor mutations Maria-Christina Zennaro1,2,3 and Fabio Fernandes-Rosa1,2,3 Correspondence 1INSERM, Paris Cardiovascular Research Center, Paris, France should be addressed 2Université Paris Descartes, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Paris, France to M-C Zennaro 3Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Service de Génétique, Email Paris, France maria-christina.zennaro@ inserm.fr Abstract Aldosterone and the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) are key elements for maintaining Key Words fluid and electrolyte homeostasis as well as regulation of blood pressure. Loss-of- f mineralocorticoid function mutations of the MR are responsible for renal pseudohypoaldosteronism type receptor 1 (PHA1), a rare disease of mineralocorticoid resistance presenting in the newborn with f pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1- PHA1 weight loss, failure to thrive, vomiting and dehydration, associated with hyperkalemia f aldosterone and metabolic acidosis, despite extremely elevated levels of plasma renin and f hormone receptors aldosterone. In contrast, a MR gain-of-function mutation has been associated with a f nuclear receptor familial form of inherited mineralocorticoid hypertension exacerbated by pregnancy. In Endocrinology addition to rare variants, frequent functional single nucleotide polymorphisms of the of MR are associated with salt sensitivity, blood pressure, stress response and depression in the general population. This review will summarize our knowledge on MR mutations in Journal PHA1, reporting our experience on the genetic diagnosis in a large number of patients performed in the last 10 years at a national reference center for the disease. -

Endocrine Drugs

PharmacologyPharmacologyPharmacology DrugsDrugs thatthat AffectAffect thethe EndocrineEndocrine SystemSystem TopicsTopicsTopics •• Pituitary Pituitary DrugsDrugs •• Parathyroid/Thyroid Parathyroid/Thyroid DrugsDrugs •• Adrenal Adrenal DrugsDrugs •• Pancreatic Pancreatic DrugsDrugs •• Reproductive Reproductive DrugsDrugs •• Sexual Sexual BehaviorBehavior DrugsDrugs FunctionsFunctionsFunctions •• Regulation Regulation •• Control Control GlandsGlandsGlands ExocrineExocrine EndocrineEndocrine •• Secrete Secrete enzymesenzymes •• Secrete Secrete hormoneshormones •• Close Close toto organsorgans •• Transport Transport viavia bloodstreambloodstream •• Require Require receptorsreceptors NervousNervous EndocrineEndocrine WiredWired WirelessWireless NeurotransmittersNeurotransmitters HormonesHormones ShortShort DistanceDistance LongLong Distance Distance ClosenessCloseness ReceptorReceptor Specificity Specificity RapidRapid OnsetOnset DelayedDelayed Onset Onset ShortShort DurationDuration ProlongedProlonged Duration Duration RapidRapid ResponseResponse RegulationRegulation MechanismMechanismMechanism ofofof ActionActionAction HypothalamusHypothalamusHypothalamus HypothalamicHypothalamicHypothalamic ControlControlControl PituitaryPituitaryPituitary PosteriorPosteriorPosterior PituitaryPituitaryPituitary Target Actions Oxytocin Uterus ↑ Contraction Mammary ↑ Milk let-down ADH Kidneys ↑ Water reabsorption AnteriorAnteriorAnterior PituitaryPituitaryPituitary Target Action GH Most tissue ↑ Growth TSH Thyroid ↑ TH secretion ACTH Adrenal ↑ Cortisol Cortex -

Agonistic and Antagonistic Properties of Progesterone Metabolites at The

European Journal of Endocrinology (2002) 146 789–800 ISSN 0804-4643 EXPERIMENTAL STUDY Agonistic and antagonistic properties of progesterone metabolites at the human mineralocorticoid receptor M Quinkler, B Meyer, C Bumke-Vogt, C Grossmann, U Gruber, W Oelkers, S Diederich and V Ba¨hr Department of Endocrinology, Klinikum Benjamin Franklin, Freie Universita¨t Berlin, Hindenburgdamm 30, 12200 Berlin, Germany (Correspondence should be addressed to M Quinkler; Email: [email protected]) Abstract Objective: Progesterone binds to the human mineralocorticoid receptor (hMR) with nearly the same affinity as do aldosterone and cortisol, but confers only low agonistic activity. It is still unclear how aldosterone can act as a mineralocorticoid in situations with high progesterone concentrations, e.g. pregnancy. One mechanism could be conversion of progesterone to inactive compounds in hMR target tissues. Design: We analyzed the agonist and antagonist activities of 16 progesterone metabolites by their binding characteristics for hMR as well as functional studies assessing transactivation. Methods: We studied binding affinity using hMR expressed in a T7-coupled rabbit reticulocyte lysate system. We used co-transfection of an hMR expression vector together with a luciferase reporter gene in CV-1 cells to investigate agonistic and antagonistic properties. Results: Progesterone and 11b-OH-progesterone (11b-OH-P) showed a slightly higher binding affinity than cortisol, deoxycorticosterone and aldosterone. 20a-dihydro(DH)-P, 5a-DH-P and 17a-OH-P had a 3- to 10-fold lower binding potency. All other progesterone metabolites showed a weak affinity for hMR. 20a-DH-P exhibited the strongest agonistic potency among the metabolites tested, reaching 11.5% of aldosterone transactivation. -

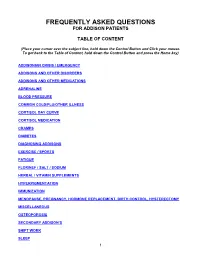

Frequently Asked Questions for Addison Patients

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS FOR ADDISON PATIENTS TABLE OF CONTENT (Place your cursor over the subject line, hold down the Control Button and Click your mouse. To get back to the Table of Content, hold down the Control Button and press the Home key) ADDISONIAN CRISIS / EMERGENCY ADDISONS AND OTHER DISORDERS ADDISONS AND OTHER MEDICATIONS ADRENALINE BLOOD PRESSURE COMMON COLD/FLU/OTHER ILLNESS CORTISOL DAY CURVE CORTISOL MEDICATION CRAMPS DIABETES DIAGNOSING ADDISONS EXERCISE / SPORTS FATIGUE FLORINEF / SALT / SODIUM HERBAL / VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTS HYPERPIGMENTATION IMMUNIZATION MENOPAUSE, PREGNANCY, HORMONE REPLACEMENT, BIRTH CONTROL, HYSTERECTOMY MISCELLANEOUS OSTEOPOROSIS SECONDARY ADDISON’S SHIFT WORK SLEEP 1 STRESS DOSING SURGICAL, MEDICAL, DENTAL PROCEDURES THYROID TRAVEL WEIGHT GAIN 2 ADDISONIAN CRISIS / EMERGENCY How do you know when to call an ambulance? If you are careful, you should not have to call an ambulance. If someone with adrenal insufficiency has gastrointestinal problems and is unable to keep down their cortisol or other glucocorticoid for more than 24 hrs, they should be taken to an emergency department so they can be given intravenous solucortef and saline. It is not appropriate to wait until they are so ill that they cannot be taken to the hospital by a family member. If the individual is unable to retain anything by mouth and is very ill, or if they have had a sudden stress such as a fall or an infection, then it would be necessary for them to go by ambulance as soon as possible. It is important that you should have an emergency kit at home and that someone in the household knows how to use it. -

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

NINDS Custom Collection II

ACACETIN ACEBUTOLOL HYDROCHLORIDE ACECLIDINE HYDROCHLORIDE ACEMETACIN ACETAMINOPHEN ACETAMINOSALOL ACETANILIDE ACETARSOL ACETAZOLAMIDE ACETOHYDROXAMIC ACID ACETRIAZOIC ACID ACETYL TYROSINE ETHYL ESTER ACETYLCARNITINE ACETYLCHOLINE ACETYLCYSTEINE ACETYLGLUCOSAMINE ACETYLGLUTAMIC ACID ACETYL-L-LEUCINE ACETYLPHENYLALANINE ACETYLSEROTONIN ACETYLTRYPTOPHAN ACEXAMIC ACID ACIVICIN ACLACINOMYCIN A1 ACONITINE ACRIFLAVINIUM HYDROCHLORIDE ACRISORCIN ACTINONIN ACYCLOVIR ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE ADENOSINE ADRENALINE BITARTRATE AESCULIN AJMALINE AKLAVINE HYDROCHLORIDE ALANYL-dl-LEUCINE ALANYL-dl-PHENYLALANINE ALAPROCLATE ALBENDAZOLE ALBUTEROL ALEXIDINE HYDROCHLORIDE ALLANTOIN ALLOPURINOL ALMOTRIPTAN ALOIN ALPRENOLOL ALTRETAMINE ALVERINE CITRATE AMANTADINE HYDROCHLORIDE AMBROXOL HYDROCHLORIDE AMCINONIDE AMIKACIN SULFATE AMILORIDE HYDROCHLORIDE 3-AMINOBENZAMIDE gamma-AMINOBUTYRIC ACID AMINOCAPROIC ACID N- (2-AMINOETHYL)-4-CHLOROBENZAMIDE (RO-16-6491) AMINOGLUTETHIMIDE AMINOHIPPURIC ACID AMINOHYDROXYBUTYRIC ACID AMINOLEVULINIC ACID HYDROCHLORIDE AMINOPHENAZONE 3-AMINOPROPANESULPHONIC ACID AMINOPYRIDINE 9-AMINO-1,2,3,4-TETRAHYDROACRIDINE HYDROCHLORIDE AMINOTHIAZOLE AMIODARONE HYDROCHLORIDE AMIPRILOSE AMITRIPTYLINE HYDROCHLORIDE AMLODIPINE BESYLATE AMODIAQUINE DIHYDROCHLORIDE AMOXEPINE AMOXICILLIN AMPICILLIN SODIUM AMPROLIUM AMRINONE AMYGDALIN ANABASAMINE HYDROCHLORIDE ANABASINE HYDROCHLORIDE ANCITABINE HYDROCHLORIDE ANDROSTERONE SODIUM SULFATE ANIRACETAM ANISINDIONE ANISODAMINE ANISOMYCIN ANTAZOLINE PHOSPHATE ANTHRALIN ANTIMYCIN A (A1 shown) ANTIPYRINE APHYLLIC -

6. Endocrine System 6.1 - Drugs Used in Diabetes Also See SIGN 116: Management of Diabetes, 2010

1 6. Endocrine System 6.1 - Drugs used in Diabetes Also see SIGN 116: Management of Diabetes, 2010 http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/116 Insulin Prescribing Guidance in Type 2 Diabetes http://www.fifeadtc.scot.nhs.uk/media/6978/insulin-prescribing-in-type-2-diabetes.pdf 6.1.1 Insulins (Type 2 Diabetes) 6.1.1.1 Short Acting Insulins 1st Choice S – Insuman ® Rapid (Human Insulin) S – Humulin S ® S – Actrapid ® 2nd Choice S – Insulin Aspart (NovoRapid ®) (Insulin Analogues) S – Insulin Lispro (Humalog ®) 6.1.1.2 Intermediate and Long Acting Insulins 1st Choice S – Isophane Insulin (Insuman Basal ®) (Human Insulin) S – Isophane Insulin (Humulin I ®) S – Isophane Insulin (Insulatard ®) 2nd Choice S – Insulin Detemir (Levemir ®) (Insulin Analogues) S – Insulin Glargine (Lantus ®) Biphasic Insulins 1st Choice S – Biphasic Isophane (Human Insulin) (Insuman Comb ® ‘15’, ‘25’,’50’) S – Biphasic Isophane (Humulin M3 ®) 2nd Choice S – Biphasic Aspart (Novomix ® 30) (Insulin Analogues) S – Biphasic Lispro (Humalog ® Mix ‘25’ or ‘50’) Prescribing Points For patients with Type 1 diabetes, insulin will be initiated by a diabetes specialist with continuation of prescribing in primary care. Insulin analogues are the preferred insulins for use in Type 1 diabetes. Cartridge formulations of insulin are preferred to alternative formulations Type 2 patients who are newly prescribed insulin should usually be started on NPH isophane insulin, (e.g. Insuman Basal ®, Humulin I ®, Insulatard ®). Long-acting recombinant human insulin analogues (e.g. Levemir ®, Lantus ®) offer no significant clinical advantage for most type 2 patients and are much more expensive. In terms of human insulin. The Insuman ® range is currently the most cost-effective and preferred in new patients. -

Steroid Use in Prednisone Allergy Abby Shuck, Pharmd Candidate

Steroid Use in Prednisone Allergy Abby Shuck, PharmD candidate 2015 University of Findlay If a patient has an allergy to prednisone and methylprednisolone, what (if any) other corticosteroid can the patient use to avoid an allergic reaction? Corticosteroids very rarely cause allergic reactions in patients that receive them. Since corticosteroids are typically used to treat severe allergic reactions and anaphylaxis, it seems unlikely that these drugs could actually induce an allergic reaction of their own. However, between 0.5-5% of people have reported any sort of reaction to a corticosteroid that they have received.1 Corticosteroids can cause anything from minor skin irritations to full blown anaphylactic shock. Worsening of allergic symptoms during corticosteroid treatment may not always mean that the patient has failed treatment, although it may appear to be so.2,3 There are essentially four classes of corticosteroids: Class A, hydrocortisone-type, Class B, triamcinolone acetonide type, Class C, betamethasone type, and Class D, hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and clobetasone-17-butyrate type. Major* corticosteroids in Class A include cortisone, hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone, and prednisone. Major* corticosteroids in Class B include budesonide, fluocinolone, and triamcinolone. Major* corticosteroids in Class C include beclomethasone and dexamethasone. Finally, major* corticosteroids in Class D include betamethasone, fluticasone, and mometasone.4,5 Class D was later subdivided into Class D1 and D2 depending on the presence or 5,6 absence of a C16 methyl substitution and/or halogenation on C9 of the steroid B-ring. It is often hard to determine what exactly a patient is allergic to if they experience a reaction to a corticosteroid.