Honduras: Information Gathering Mission Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIFE and WORK in the BANANA FINCAS of the NORTH COAST of HONDURAS, 1944-1957 a Dissertation

CAMPEÑAS, CAMPEÑOS Y COMPAÑEROS: LIFE AND WORK IN THE BANANA FINCAS OF THE NORTH COAST OF HONDURAS, 1944-1957 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Suyapa Gricelda Portillo Villeda January 2011 © 2011 Suyapa Gricelda Portillo Villeda CAMPEÑAS Y CAMPEÑOS: LIFE AND WORK IN THE BANANA FINCAS OF THE NORTH COAST OF HONDURAS, 1944-1957 Suyapa Gricelda Portillo Villeda, Ph.D. Cornell University 2011 On May 1st, 1954 banana workers on the North Coast of Honduras brought the regional economy to a standstill in the biggest labor strike ever to influence Honduras, which invigorated the labor movement and reverberated throughout the country. This dissertation examines the experiences of campeños and campeñas, men and women who lived and worked in the banana fincas (plantations) of the Tela Railroad Company, a subsidiary of the United Fruit Company, and the Standard Fruit Company in the period leading up to the strike of 1954. It describes the lives, work, and relationships of agricultural workers in the North Coast during the period, traces the development of the labor movement, and explores the formation of a banana worker identity and culture that influenced labor and politics at the national level. This study focuses on the years 1944-1957, a period of political reform, growing dissent against the Tiburcio Carías Andino dictatorship, and worker agency and resistance against companies' control over workers and the North Coast banana regions dominated by U.S. companies. Actions and organizing among many unheralded banana finca workers consolidated the powerful general strike and brought about national outcomes in its aftermath, including the state's institution of the labor code and Ministry of Labor. -

Overcoming Violence and Impunity: Human Rights Challenges in Honduras

OVERCOMING VIOLENCE AND IMPUNITY: HUMAN RIGHTS CHALLENGES IN HONDURAS Report of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development Dean Allison Chair Subcommittee on International Human Rights Scott Reid Chair MARCH 2015 41st PARLIAMENT, SECOND SESSION Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. Nothing in this permission abrogates or derogates from the privileges, powers, immunities and rights of the House of Commons and its Committees. For greater certainty, this permission does not affect the prohibition against impeaching or questioning the proceedings of the House of Commons in courts or otherwise. The House of Commons retains the right and privilege to find users in contempt of Parliament if a reproduction or use is not in accordance with this permission. -

Political Culture of Democracy in Honduras and in the Americas, 2014

The Political Culture of Democracy in Honduras and in the Americas, 2014: Democratic Governance across 10 Years of the AmericasBarometer By: Orlando J. Pérez, Ph.D. Millersville University Elizabeth J. Zechmeister, Ph.D. LAPOP Director and Series Editor Vanderbilt University This study was performed with support from the Program in Democracy and Governance of the United States Agency for International Development. The opinions expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the point of view of the United States Agency for International Development. January 2015 Table of Contents Table of Contents List of Figures ....................................................................................................................................... vii List of Maps ............................................................................................................................................ xi List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................... xi Preface .................................................................................................................................................. xiii Prologue: Background to the Study .................................................................................................... xv Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. xxv Introduction -

Cure Violence Using a Health Approach

VIOLENCE IS CONTAGIOUS; WE CAN TREAT AND, ULTIMATELY, CURE VIOLENCE USING A HEALTH APPROACH cureviolence.org I #cureviolence REPORT ON THE CURE VIOLENCE MODEL ADAPTATION IN SAN PEDRO SULA, HONDURAS FreeImages.com/ Benjamin Earwicker FreeImages.com/ Charles Ransford, MPP R. Brent Decker, MSW, MPH Gary Slutkin, MD Cure Violence University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health Abstract: San Pedro Sula, Honduras has had the highest levels of killing of any city around the world for several years. Violence in San Pedro is multi-faceted and has become normalized by those forced to live with it. The Cure Violence model to stopping violence is an epidemic control model that reduces violence by changing norms and behaviors and has been proven effective in the community setting. In 2012, Cure Violence conducted an extensive assessment of the violence in several potential program zones in San Pedro Sula and in April 2013 began implementing an adapted version of the model. In 2014, the first three zones implementing the model experienced a 73% reduction in shootings and killings compared to the same 9-month period in 2013. In the first 5 months of 2015, five program zones experienced an 88% reduction in shootings and killing, including one site that went 17 months without any shootings. November 2016 Violence in Honduras The Americas are the most violent region in the world with an average homicide rate of 28.5 per 100,000 and an estimated 165,617 killing in 2012.1 In total, the Americas account for roughly 36% of global homicides.2 Within this most violent region, violence is most severe in the Northern Triangle of Latin Amer- ica, an area that includes El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. -

Basques in the Americas from 1492 To1892: a Chronology

Basques in the Americas From 1492 to1892: A Chronology “Spanish Conquistador” by Frederic Remington Stephen T. Bass Most Recent Addendum: May 2010 FOREWORD The Basques have been a successful minority for centuries, keeping their unique culture, physiology and language alive and distinct longer than any other Western European population. In addition, outside of the Basque homeland, their efforts in the development of the New World were instrumental in helping make the U.S., Mexico, Central and South America what they are today. Most history books, however, have generally referred to these early Basque adventurers either as Spanish or French. Rarely was the term “Basque” used to identify these pioneers. Recently, interested scholars have been much more definitive in their descriptions of the origins of these Argonauts. They have identified Basque fishermen, sailors, explorers, soldiers of fortune, settlers, clergymen, frontiersmen and politicians who were involved in the discovery and development of the Americas from before Columbus’ first voyage through colonization and beyond. This also includes generations of men and women of Basque descent born in these new lands. As examples, we now know that the first map to ever show the Americas was drawn by a Basque and that the first Thanksgiving meal shared in what was to become the United States was actually done so by Basques 25 years before the Pilgrims. We also now recognize that many familiar cities and features in the New World were named by early Basques. These facts and others are shared on the following pages in a chronological review of some, but by no means all, of the involvement and accomplishments of Basques in the exploration, development and settlement of the Americas. -

Deportation, Circular Migration and Organized Crime Honduras Case Study

Deportation, Circular Migration and Organized Crime Honduras Case Study by Geoff Burt, Michael Lawrence, Mark Sedra, James Bosworth, Philippe Couton, Robert Muggah and Hannah Stone RESEARCH REPORT: 2016–R006 RESEARCH DIVISION www.publicsafety.gc.ca Abstract This research report examines the impact of criminal deportation to Honduras on public safety in Canada. It focuses on two forms of transnational organized crime that provide potential, though distinct, connections between the two countries: the youth gangs known as the maras, and the more sophisticated transnational organized crime networks that oversee the hemispheric drug trade. In neither case does the evidence reveal direct links between criminal activity in Honduras and criminality in Canada. While criminal deportees from Canada may join local mara factions, they are unlikely to be recruited by the transnational networks that move drugs from South America into Canada. The relatively small numbers of criminal deportees from Canada, and the difficulty of returning once deported, further impede the development of such threats. As a result, the direct threat to Canadian public safety posed by offenders who have been deported to Honduras is minimal. The report additionally examines the pervasive violence and weak institutional context to which deportees return. The security and justice sectors of the Honduran government are clearly overwhelmed by the violent criminality afflicting the country, and suffer from serious corruption and dysfunction. Given the lack of targeted reintegration programs for criminal returnees, deportation from Canada and the United States likely exacerbates the country’s insecurity. The report concludes with a number of possible policy recommendations by which Canada can reduce the harm that criminal deportation poses to Honduras, and strengthen state institutions so that they can prevent the presently insignificant threats posed to Canada by Honduran crime from growing in the future. -

Capitulo 1:Contexto Fisico

1 CAPITULO 1:CONTEXTO FISICO 1.1 CARACTERIZACION GENERAL DEL MUNICIPIO 1.1.1 Antecedentes Históricos Las primeras poblaciones del Municipio de Potrerillos datan del año 1843, siendo los primeros habitantes las familias Godoy, Castro y Triminio. En ese entonces existían únicamente 18 champas hechas de manaca y bambú y establecidas en las cercanías del río Ulúa. La actividad principal era la pesca, la caza y el cultivo del banano en las vegas del mismo río. Se ocupaban también de la exportación de la mora y de madera preciosa. Estas comunidades formaban parte del Departamento de Santa Bárbara y fue al General Luis Bográn, gobernador político, quien creó el nuevo municipio el 3 de marzo de 1875 -aunque de hecho ya existencia desde el año 1871. 1.1.2 Ubicación, Tamaño y Límites Territoriales Actualmente el Municipio de Potrerillos pertenece al Departamento de Cortés (ver mapa de la siguiente página) y está ubicado en la parte Sur del Valle de Sula, siendo el segundo más pequeño en extensión territorial, seguido de Pimienta en el contexto departamental. Es atravesado por la carretera interoceánica que va desde el norte hasta el sur del país. La superficie territorial es de 88.4 kilómetros cuadrados, de los cuales 6% de la superficie corresponden al casco urbano y 94% al área rural. El casco urbano cuenta con 23 barrios y colonias y el área rural, con 8 aldeas y 5 caseríos. En el anexo No. 1 se lista los barrios, colonias, aldeas y caseríos del término municipal. En cuanto a los límites territoriales, el municipio limita al norte con los municipios de Pimienta y Villanueva, Departamento de Cortés; al este, con el municipio de Santa Rita, Departamento de Yoro; al oeste, con el Municipio de San Antonio de Cortés, Departamento de Cortés; y al sur, con el Municipio de Santa Cruz de Yojoa, Departamento de Cortés. -

Global Shelter Cluster Meeting 2021 the SHELTER CLUSTER in HONDURAS Wednesday, 18 August 2021 – 14:00 CEST/06:00 CST Agenda

Country Presentations - Global Shelter Cluster Meeting 2021 THE SHELTER CLUSTER IN HONDURAS Wednesday, 18 August 2021 – 14:00 CEST/06:00 CST Agenda Time (CEST) Subject Who 14.00-14.05 Introduction Lilia Blades 14.05-14.15 Background & Key figures Toni Ros & Lilia Blades 14.15-14.20 Main issues Cluster partners 14.20-14.30 Strategy Cluster coordinators 14.30-14.40 Questions so Far All 14.40-14.55 Projects by Proyecto Aldea Global and NRC Chester Thomas and Esther Menduiña 14.55-15 Wrap-Up Cluster coordinators 15.00 End of Meeting Mesa de coordinación de Alojamiento de Emergencia - Honduras Coordinando el alojamiento de emergencia www.sheltercluster.org/node/19986 2 Timeline of the response Eta - Category 4 hurricane Activation of the Shelter working group More than 42,000 displaced people 82,307 damaged houses (COPECO-Permanent Committee for More than 9,000 houses completely Contingencies in Honduras) destroyed Shelter needs assessments focused on 12,495 families remained in damaged families in collective centers houses 174,241 people remain in collective centers (COPECO) HCT reactivates the COVID-19 sectoral working groups Nov 17, 2020 January 2021 Nov 3, 2020 Dec 3, 2020 Iota - Category 5 hurricane Official activation of the IASC Cluster coordination system in Honduras Further flooding, landslides, several communities are completely inaccessible Displaced families unable to return Ad-hoc Meeting of local and international shelter agencies 3 Mesa de coordinación de Alojamiento de Emergencia - Honduras Coordinando el alojamiento de emergencia www.sheltercluster.org/node/19986 Honduras Shelter cluster Jointly led by IFRC and Global Communities 19 active members ● 3 government agencies: CENISS, CONVIVIENDA, AMHON ● 3 national organizations: Proyecto Aldea Global, CRH, FUNADEH, ● 10 international NGOs: HFHI, TECHO, NRC, Save the Children, ShelterBox, CRS, Global Communities, CARE, GOAL, GER3. -

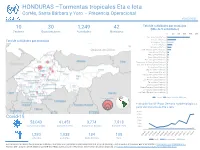

Presentación De Powerpoint

HONDURAS –Tormentas tropicales Eta e Iota Cortés, Santa Bárbara y Yoro – Presencia Operacional al 2021/01/25 Total de actividades por municipio 10 30 1,249 42 (Más de 5 actividades) Sectores Organizaciones Actividades Municipios 0 100 200 300 400 500 San Pedro Sula (Cortés) Choloma (Cortés) Total de actividades por municipio El Progreso (Yoro) La Lima (Cortés) Villanueva (Cortés) Océano Atlántico Santa Bárbara (Santa Bárbara) San Manuel (Cortés) Atima (Santa Bárbara) Ilama (Santa Bárbara) Macuelizo (Santa Bárbara) Concepción del Norte (Santa Bárbara) San José de Colinas (Santa Bárbara) Arada (Santa Bárbara) Ceguaca (Santa Bárbara) Puerto Cortés (Cortés) Nuevo Celilac (Santa Bárbara) Gualala (Santa Bárbara) San Nicolás (Santa Bárbara) Petoa (Santa Bárbara) Chinda (Santa Bárbara) Nueva Frontera (Santa Bárbara) San Marcos (Santa Bárbara) San Pedro Zacapa (Santa Bárbara) Cortés Santa Bárbara Yoro Total de actividades 350 350150 Evolución Covid-19 por Semana Epidemiológica a 30 partir del impacto de Eta e Iota 3,000 2,500 Covid-19 2,000 1,500 53,043 41,451 3,774 7,818 1,000 Casos acumulados Casos en Cortés Casos en S. Bárbara Casos en Yoro 500 - 1,280 1,038 134 108 Fallecidos en Cortés Santa Bárbara Yoro Cortés Santa Bárbara Yoro Las fronteras, nombres y designaciones utilizadas no implica una ratificación o aceptación oficial de parte de Naciones Unidas. Fecha de creación: Enero 25 de 2020 / [email protected] [email protected] Fuentes: EHP, Sistema 345W, Monitor Covid19 OPS-OMS, Secretaría Salud Honduras. Información detallada disponible en: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/honduras -

China-Venezuela Economic Relations: Hedging Venezuelan Bets with Chinese Characteristics1

Latin American Program | Kissinger Institute | February 2019 Chinese President Xi Jinping, right, shakes hands with Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro, Sept. 22, 2013. © Lintao Zhang / AP Photo China-Venezuela Economic Relations: 1 Hedging Venezuelan Bets with Chinese Characteristics LATIN AMERICAN PROGRAM LATIN AMERICAN PROGRAM Stephen B. Kaplan and Michael Penfold KISSINGER INSTITUTE Tens of thousands of Venezuelans raised their hands toward the sky on January 23, 2019, to offer solidarity to legislative leader, Juan Guaidó, who declared himself interim president of LATIN AMERICAN PROGRAM Venezuela during a rally demanding President Nicolás Maduro’s resignation. Refusing to rec- ognize the legitimacy of Maduro’s May 2018 re-election, Guaidó cited his constitutional duty as the head of the National Assembly to fill the presidential vacancy until new elections were called. Hand in hand with Guaidó, the United States unequivocally supported his declaration, recognizing him as Venezuela’s head of state. Backed by Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Co- lombia, Israel, and Peru, President Trump said he would “use the full weight of United States economic and diplomatic power to press for the restoration of Venezuelan democracy.” More recently, Spain, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany also recognized Guaidó as interim president after Maduro failed to call new elections. The United States also backed its position with some economic muscle, imposing sanctions on Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PdVSA), saying that all PdVSA assets, including its oil sale pro- ceeds, will be frozen in U.S. jurisdictions. 1 The authors would like to thank Cindy Arnson and Robert Daly for their insightful commentary about China-Latin American relations, Marcin Jerzewski, Beverly Li, and Giorgos Morakis for their superb research assistance, and Orlando Ochoa, Francisco Monaldi, and Francisco Rodríguez for invaluable conversations about the current state of the Venezuelan economy and oil sector. -

Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR12197 Implementation Status & Results Honduras Second Land Administration Project (P106680) Operation Name: Second Land Administration Project (P106680) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 5 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 20-Nov-2013 Country: Honduras Approval FY: 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: LATIN AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN Lending Instrument: Adaptable Program Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Board Approval Date 30-Jun-2011 Original Closing Date 30-Jan-2017 Planned Mid Term Review Date 08-Sep-2014 Last Archived ISR Date 24-Apr-2013 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 21-Nov-2011 Revised Closing Date 30-Jan-2017 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) Provide the population in the Project Area with improved, decentralized land administration services, including better access to and more accurate information on property records and transactions. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Policy and Institutional Strengthening 9.00 Cadastral Surveying and Land Regularization 18.00 Demarcation of Protected Areas 0.50 Strengthening of Miskito People's Land Rights 1.80 Project Management and Monitoring and Evaluation 3.50 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Public Disclosure Authorized Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Substantial Substantial Implementation Status Overview Public Disclosure Copy The Project is the second phase of a long-term program of the Government of Honduras aimed at modernizing the land administration system of the country. -

Municipio De Santa Cruz De Yojoa Departamento De Cortés Plan Municipal De Gestión De Riesgo Y Propuesta De Zonificaci

REPÚBLICA DE HONDURAS COMISIÓN PERMANENTE DE CONTINGENCIAS (COPECO) CRÉDITO AIF No. 5190-HN PROYECTO GESTIÓN DE RIESGOS DE DESASTRES Plan Municipal de Gestión de Riesgo y Propuesta de Zonificación Territorial Municipio de Santa Cruz de Yojoa Departamento de Cortés Marzo, 2017 REPÚBLICA DE HONDURAS COMISIÓN PERMANENTE DE CONTINGENCIAS (COPECO) CRÉDITO AIF No. 5190-HN PROYECTO GESTIÓN DE RIESGOS DE DESASTRES CONTENIDO SIGLAS Y ACRÓNIMOS .................................................................................................................................................. 7 PRESENTACIÓN ............................................................................................................................................................ 9 INTRODUCCIÓN .......................................................................................................................................................... 10 ANTECEDENTES .......................................................................................................................................................... 12 1. ASPECTOS GENERALES ....................................................................................................................................... 15 1.1. MARCO CONCEPTUAL ...................................................................................................................................... 15 1.2. CONSIDERACIONES METODOLÓGICAS .................................................................................................................