Conservation and Development of Military Sites on Kinmen Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xiamen Government Requirements and Control Measures for Ships in Waters of Xiamen Port Area

MEMBER ALERT Shipowners Claims Bureau, Inc., Manager One Battery Park Plaza 31st Fl., New York, NY 10004 USA Tel: +1 212 847 4500 Fax: +1 212 847 4599 www.american-club.com AUGUST 9, 2017 PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA: XIAMEN GOVERNMENT REQUIREMENTS AND CONTROL MEASURES FOR SHIPS IN WATERS OF XIAMEN PORT AREA The Xiamen People’s Government recently issued a Notice on Implementing Temporary Requirements and Control Measures over Ships in Waters of the Port Area of Xiamen Bay during the Major International Event. This is aimed at ensuring the smoothness of the BRICS summit, which will be held in Xiamen between September 3 and 5, 2017. In this connection, reference is made to the attached circular from the Club’s correspondent, Huatai Insurance Agency & Consultant Service Ltd. Members are encouraged to note this requirement and take action accordingly. Your Managers thank Huatai Insurance Agency & Consultant Service Ltd., Qingdao Branch, People’s Republic of China, for this information. 7 , 201 9 August – American Club Member Alert Alert Member Club American 1 Circular Ref No.: PNI1707 Date: 4 August 2017 Dear Sirs or Madam, Subject: Xiamen People’s Government Issued a Notice on Temporary Requirements and Control Measures over Ships in Waters of Xiamen Port area during the Major International Event (This circular is prepared by Huatai Xiamen office) On 28 June 2017, Xiamen People’s Government issued a Notice on Implementing Temporary Requirements and Control Measures over Ships in Waters of the Port Area of Xiamen Bay during the Major International Event for ensuring the smoothness of the BRICS summit, which will be held in Xiamen between 03 and 05 September 2017. -

Taiwan and China's Cross-Strait Relations" (2018)

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-18-2018 Contending Identities: Taiwan and China's Cross- Strait Relations Jing Feng [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Recommended Citation Feng, Jing, "Contending Identities: Taiwan and China's Cross-Strait Relations" (2018). Master's Projects and Capstones. 777. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/777 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Contending Identities: Taiwan and China’s Cross-Strait Relationship Jing Feng Capstone Project APS 650 Professor Brian Komei Dempster May 15, 2018 2 Abstract Taiwan’s strategic geopolitical position—along with domestic political developments—have put the country in turmoil ever since the post-Chinese civil war. In particular, its antagonistic, cross-strait relationship with China has led to various negative consequences and cast a spotlight on the country on the international diplomatic front for close to over six decades. After the end of the Cold War, the democratization of Taiwan altered her political identity and released a nation-building process that was seemingly irreversible. Taiwan’s nation-building efforts have moved the nation further away from reunification with China. -

Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations: What Are the Legitimate Expectations from the WTO Qingjiang Kong

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Journal of International Law 2005 Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations: What Are the Legitimate Expectations from the WTO Qingjiang Kong Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjil Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kong, Qingjiang, "Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations: What Are the Legitimate Expectations from the WTO" (2005). Minnesota Journal of International Law. 220. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjil/220 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Journal of International Law collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations: What are the Legitimate Expectations from the WTO? Qingjiang Kong* INTRODUCTION On December 11, 2001, China acceded to the World Trade Organization (WTO).1 Taiwan followed on January 1, 2002 as the "Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu."2 Accession of both China and Taiwan to the world trading body has triggered a fever of activities by Taiwanese businesses, but the governments on both sides of the Taiwan Strait have been slow to make policy adjustments. The coexis- tence of business enthusiasm and governmental indifference * Professor of International Economic Law, Zhejiang Gongshang University (previ- ously: Hangzhou University of Commerce), China. His recent book is China and the World Trade Organization:A Legal Perspective (New Jersey, London, Singapore, Hong Kong, World Scientific Publishing, 2002). Questions or comments may be e- mailed to Professor Kong at [email protected]. -

Counterguerrilla Operation

FM 90-8 counterguerrilla operation/ AUGUST 1986 This publication contains technical or operational information that is for official government use only. Distribution is limited to US Government agencies Requests from outside the US Government for release of this publication under the Freedom of Information Act or the Foreign Military Sales Program must be made to: HO TR ADOC, Fort Monroe, VA 23651 ... HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION- Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. FM 90-8 CHAPTER 6. COMBAT SUPPORT Section I. General ............................................ 6-1 II. Reconnaissance and Surveillance Units ............. 6-2 Ill. Fire Support Units ................................. 6-7 CHAPTER 7. COMBAT SERVICE SUPPORT Section I. General ............................................ 7-1 II. Bases ............................................. 7-1 Ill. Use of Assets ...................................... 7-3 APPENDIX A. SUBSURFACE OPERATIONS Section I. General ............................................ A-1 II. Tunneling .......................................... A-2 Ill. Destroying Underground Facilities ................. A-12 APPENDIX B. THE URBAN GUERRILLA Section I. General ............................................ B-1 II. Techniques to Counter the Urban Guerrilla .......... B-2 APPENDIX C. AMBUSH PATROLS Section I. General ............................................ C-1 II. Attack Fundamentals .............................. C-2 Ill. Planning .......................................... -

Chen Muddies Cross-Strait Waters

China-Taiwan Relations: Chen Muddies Cross-Strait Waters by David G. Brown Associate Director, Asian Studies The Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies On Aug. 3, President Chen Shui-bian told a video conference with independence supporters in Tokyo that there was “one country on each side” of the Taiwan Strait. Taiwan government officials, Washington, and Beijing were caught by surprise and concerned. Taipei quickly sent out assurances that policy has not changed, Washington reiterated that it did not support independence, and President Chen refrained from repeating this remark publicly. While no crisis occurred, the remarks appear in part to reflect Chen’s conclusion that Beijing’s cool response to Taipei’s goodwill offers means there is little near-term prospect for progress on cross-Strait issues. Taipei has pressed ahead with efforts to strengthen ties with the U.S., but its efforts to increase Taiwan’s international standing have suffered setbacks. Minor steps continue to be taken to ease restrictions on cross-Strait economic ties, which are again expanding rapidly. “Three Links” in Limbo This quarter opened with considerable attention on both sides of the Strait to ways the recently concluded extension of the Taiwan-Hong Kong Air Services Agreement could provide a model for how private groups might handle the opening of direct travel across the Strait − the so-called “three links.” President Chen seemed intent on opening direct travel before the 2004 presidential elections in order to demonstrate his ability to successfully manage cross-Strait relations. Bureaucrats in Taipei were working on the modalities for authorizing private groups to negotiate. -

Spatial Construction, Form and Effectiveness Analysis of Large

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 12 September 2020 Spatial Construction, Form and Effectiveness Analysis of Large-scale Waterfront Park System in Island-type Cities ——The case of Xiamen, China SANGXIAOLEI Chih-Hong Huang Abstract: The bay is a space barrier for the development of island-type cities and a high-quality waterfront landscape resource. This study takes Xiamen a typical island city in China as an example. First, It use the method of satellite telemetry technology combined with GIS software and spatial syntax, respectively, from the material space level and social space level, to summarize the rapid urbanization process of this city since 1990-2018, focusing on the construction process of three large-scale waterfront park systems in the transition period of inter-island development in it, and comparing the similarities and differences of their spatial forms. Further, from the choice of the axis model and the integrated analysis results, we discuss the spatial efficiency changes. The construction of the three major bay waterfront park systems in this city reflects a huge change in development pattern from lagging construction, synchronous planning, to advanced layout, providing a continuous and variable spatial form for the development of the bay region and improving space efficiency, which one of the important ways to develop and transform island-type cities. We hope to provide the reference for the development including sustainable development of other island cities around the world. Keywords: island-type city, city park, waterfront area, space syntax Foreword There are huge differences in the spatial level between island-type cities and other inland- type cities, leading to different ways of urban park system construction and development characteristics. -

Scoring One for the Other Team

FIVE TURTLES IN A FLASK: FOR TAIWAN’S OUTER ISLANDS, AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE HOLDS A CERTAIN FATE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES MAY 2018 By Edward W. Green, Jr. Thesis Committee: Eric Harwit, Chairperson Shana J. Brown Cathryn H. Clayton Keywords: Taiwan independence, offshore islands, strait crisis, military intervention TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables ................................................................................................................ ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 II. Scope and Organization ........................................................................................... 6 III. Dramatis Personae: The Five Islands ...................................................................... 9 III.1. Itu Aba ..................................................................................................... 11 III.2. Matsu ........................................................................................................ 14 III.3. The Pescadores ......................................................................................... 16 III.4. Pratas ....................................................................................................... -

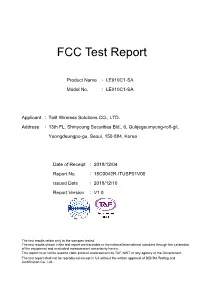

FCC Test Report

FCC Test Report Product Name : LE910C1-SA Model No. : LE910C1-SA Applicant : Telit Wireless Solutions CO., LTD. Address : 13th FL. Shinyoung Securities Bld., 6, Gukjegeumyung-ro8-gil, Yeongdeungpo-gu, Seoul, 150-884, Korea Date of Receipt : 2018/12/04 Report No. : 18C0042R-ITUSP01V00 Issued Date : 2018/12/10 Report Version : V1.0 The test results relate only to the samples tested. The test results shown in the test report are traceable to the national/international standard through the calibration of the equipment and evaluated measurement uncertainty herein. This report must not be used to claim product endorsement by TAF, NIST or any agency of the Government. The test report shall not be reproduced except in full without the written approval of DEKRA Testing and Certification Co., Ltd.. Report No:18C0042R-ITUSP01V00 Test Report Certification Issued Date : 2018/12/10 Report No. : 18C0042R-ITUSP01V00 Product Name : LE910C1-SA Applicant : Telit Wireless Solutions CO., LTD. Address : 13th FL. Shinyoung Securities Bld., 6, Gukjegeumyung-ro8-gil, Yeongdeungpo-gu, Seoul, 150-884, Korea Manufacturer : Telit Wireless Solutions CO., LTD. Model No. : LE910C1-SA EUT Voltage : DC 3.8V Trade Name : Applicable Standard : FCC CFR Title 47 Part 15 Subpart B: 2017 Class B, CISPR 22: 2008, ICES-003 Issue 6: 2016 Class B, ANSI C63.4: 2014 Test Result : Complied Laboratory Name : Hsin Chu Laboratory Address : No.372-2, Sec. 4, Zhongxing Rd., Zhudong Township, Hsinchu County 310, Taiwan, R.O.C. TEL: +886-3-582-8001 / FAX: +886-3-582-8958 Documented By : ( Demi Chang / Senior Engineering Adm. Specialist ) Tested By : ( Hornet Liu / Senior Engineer ) Approved By : ( Arthur Liu / Deputy Manager ) Page: 2 of 22 Report No:18C0042R-ITUSP01V00 Laboratory Information We , DEKRA Testing and Certification Co., Ltd., are an independent EMC and safety consultancy that was established the whole facility in our laboratories. -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Relative Timing of Human Migration and Land-Cover and Land-Use Change — An Evaluation of Northern Taiwan from 1990 to 2015 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8t5432st Author Shih, Hsiao-chien Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California SAN DIEGO STATE UNIVERSITY AND UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara The Relative Timing of Human Migration and Land-Cover and Land-Use Change — An Evaluation of Northern Taiwan from 1990 to 2015 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Geography by Hsiao-chien Shih Committee in charge: Professor Douglas A. Stow, Chair Professor John R. Weeks Professor Dar A. Roberts Professor Konstadinos G. Goulias June 2020 The dissertation of Hsiao-chien Shih is approved. ____________________________________________ Konstadinos G. Goulias ____________________________________________ Dar A. Roberts ____________________________________________ John R. Weeks ____________________________________________ Douglas A. Stow, Committee Chair May 2020 The Relative Timing of Human Migration and Land-Cover and Land-Use Change — An Evaluation of Northern Taiwan from 1990 to 2015 Copyright © 2020 by Hsiao-chien Shih iii Dedicated to my grandparents, my mother, and Yi-ting. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study was funded by Yin Chin Foundation of U.S.A., STUF United Fund Inc., the Long Jen-Yi Travel fund, William & Vivian Finch Scholarship, and a doctoral stipend through San Diego State University. I would like to thank for the committee members of my dissertation, Drs. Stow, Weeks, Roberts, and Goulias along with other professors. -

The Checklist of Inland-Water and Mangrove Fish Fauna of Kinmen Island, Fujian Province, Taiwan with Comments on Ecological Conservation of Native Fishes

316 Journal of Marine Science and Technology, Vol. 21, Suppl., pp. 316-319 (2013) DOI: 10.6119/JMST-013-1226-1 THE CHECKLIST OF INLAND-WATER AND MANGROVE FISH FAUNA OF KINMEN ISLAND, FUJIAN PROVINCE, TAIWAN WITH COMMENTS ON ECOLOGICAL CONSERVATION OF NATIVE FISHES I-Shiung Chen1, Chia-Jun Weng2, Yi-Ru Chen2, Shih-Pin Huang1, Zong-Han Wen1, Nian-Hong Jang-Liaw1, and Tsung-Hsien Tsai1 Key words: fish fauna, new record, endangered species, fish con- I. INTRODUCTION servation. The Kinmen island is located in the river mouth opening of Julongjiang River basin of Fujian Province, the territory be- ABSTRACT longing to Taiwan, ROC. In the earlier stage of 1960, the fauna of inlandwater fishes has been formally reported by The ecological status of the lowland freshwater and brack- Cheng TR [5] and he firstly mentioned about the occurrence of ish fish fauna traditionally got better protected since long time Rasborinus takakii (Oshima) [7] which found from Kinmen for military protect region without great human and agricul- waters. However, Rasborinus takakii (Oshima) has been re- ture impact in last few decades. However, many human garded as a junior synonym of Metzia mesembrinum (Jordan & reconstruction of river habitats, pollution and overuse of irri- Evermann) [6]. gation from river water have become great impact for fish In this island, the ecological status of the lowland fresh- survival in Kinmen. So far, there are totally 27 families, 57 water and brackish fish fauna traditionally got better protected genera and 68 species have been collected and recorded by our since long time for military protect region without great hu- intensive survey for those freshwater habitats in inlandwater man and agriculture impact in last few decades. -

Kinmen County Tourist Map(.Pdf)

Kinmen Northeaest Port Channel Houyu Island Xishan Islet (Hou Islet) Mashan Observation Station Fongsueijiao Index Mashan Broadcast Station Mashan Mr. Tianmo Guijiaowei Houyupo Scenic Spots\Historic Spots Caoyu Island Three Widows Chastity Arch Kuige (Kuixing Tower) West Reef Mr. Caoyu Victory Memorial of August 23 Artillery Battle Maoshan Pagoda Guanaojiao Reef Jhenwutou August 23 Artillery Battle Daoying Pagoda Kinmen Temple Dongge Museum M Guanao Victory Memorial of August 23 Liaoluo Seashore Park Kinmen County Tourist Map CM M Artillery Battle Fanggang Fishing Port Shaqing Rd. Yunei Reef Bada Tower Pubian Chou/Zhou Residence Qingyu The 11-Generations Ancestral Siyuanyu Island Haiyin Temple Longfong Temple Mashan-Yongshih Fort Shrine Tangtou Sun Yat-sen Memorial Forest Chaste Maiden Temple Famous monasteries and temples Airport Market / Supermarkets Decorated archway Military bunker / Ancient arch Legend Topography Administrative Division Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Lieyu North Wind God• Mr. Wulong Shumei E.S. Dongge Bay Forest Wind Chicken Rocky Coast Provincial Government Park Port / Lighthouse Gas Station / Bus Station Monument Bird-watching area Wuhushan Hiking Trail Scholar Wu’s Abode, Lieyu Martyr Garden Main road Air Line County / City Hall Cinema / Stadium Chunghwa Telecom Bus stop Cemetery Flower District Xiyuan Beach Guanghua Rd. Sec. 2 Tomb of Wang Shijie Victory Gate, Leiyu College/University Junior/ TAIWAN STRAIT Township Office Broadcast / TV station Tour bus stop Checkpoints Maple District Xiyuan Rd. Generally path Dike Senior High School The 6-Generations and Mr. Sanshih 10-Generations Ancestral Shrines Lieyu Township Cultural Hall Suspension bridge Shishan Beach Police Agency Elementary School Auto repair center display Public toilets Travel leisure Ranch / Farm Xiyuan Jingshan Temple Mt. -

![[カテゴリー]Location Type [スポット名]English Location Name [住所](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8080/location-type-english-location-name-1138080.webp)

[カテゴリー]Location Type [スポット名]English Location Name [住所

※IS12TではSSID"ilove4G"はご利用いただけません [カテゴリー]Location_Type [スポット名]English_Location_Name [住所]Location_Address1 [市区町村]English_Location_City [州/省/県名]Location_State_Province_Name [SSID]SSID_Open_Auth Misc Hi-Life-Jingrong Kaohsiung Store No.107 Zhenxing Rd. Qianzhen Dist. Kaohsiung City 806 Taiwan (R.O.C.) Kaohsiung CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc Family Mart-Yongle Ligang Store No.4 & No.6 Yongle Rd. Ligang Township Pingtung County 905 Taiwan (R.O.C.) Pingtung CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc CHT Fonglin Service Center No.62 Sec. 2 Zhongzheng Rd. Fenglin Township Hualien County Hualien CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc FamilyMart -Haishan Tucheng Store No. 294 Sec. 1 Xuefu Rd. Tucheng City Taipei County 236 Taiwan (R.O.C.) Taipei CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc 7-Eleven No.204 Sec. 2 Zhongshan Rd. Jiaoxi Township Yilan County 262 Taiwan (R.O.C.) Yilan CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc 7-Eleven No.231 Changle Rd. Luzhou Dist. New Taipei City 247 Taiwan (R.O.C.) Taipei CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Restaurant McDonald's 1F. No.68 Mincyuan W. Rd. Jhongshan District Taipei CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Restaurant Cobe coffee & beauty 1FNo.68 Sec. 1 Sanmin Rd.Banqiao City Taipei County Taipei CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc Hi-Life - Taoliang store 1F. No.649 Jhongsing Rd. Longtan Township Taoyuan County Taoyuan CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc CHT Public Phone Booth (Intersection of Sinyi R. and Hsinsheng South R.) No.173 Sec. 1 Xinsheng N. Rd. Dajan Dist. Taipei CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc Hi-Life-Chenhe New Taipei Store 1F. No.64 Yanhe Rd. Anhe Vil. Tucheng Dist. New Taipei City 236 Taiwan (R.O.C.) Taipei CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc 7-Eleven No.7 Datong Rd.