Gender, Genre, and Race in Post-Neo-Slave Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

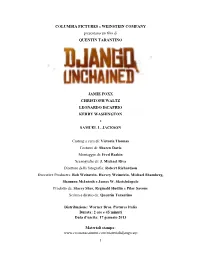

Django Unchained

COLUMBIA PICTURES e WEINSTEIN COMPANY presentano un film di QUENTIN TARANTINO JAMIE FOXX CHRISTOPH WALTZ LEONARDO DiCAPRIO KERRY WASHINGTON e SAMUEL L. JACKSON Casting a cura di: Victoria Thomas Costumi di: Sharen Davis Montaggio di: Fred Raskin Scenografie di: J. Michael Riva Direttore della fotografia: Robert Richardson Executive Producers: Bob Weinstein, Harvey Weinstein, Michael Shamberg, Shannon McIntosh e James W. Skotchdopole Prodotto da: Stacey Sher, Reginald Hudlin e Pilar Savone Scritto e diretto da: Quentin Tarantino Distribuzione: Warner Bros. Pictures Italia Durata: 2 ore e 45 minuti Data d’uscita: 17 gennaio 2013 Materiali stampa: www.cristianacaimmi.com/materialidjango.zip 1 DJANGO UNCHAINED Sinossi Ambientato nel Sud degli Stati Uniti due anni prima dello scoppio della Guerra Civile, Django Unchained vede protagonista il premio Oscar® Jamie Foxx nel ruolo di Django, uno schiavo la cui brutale storia con il suo ex padrone, lo conduce faccia a faccia con il Dott. King Schultz (il premio Oscar® Christoph Waltz), il cacciatore di taglie di origine tedesca. Schultz è sulle tracce dei fratelli Brittle, noti assassini, e solo l’aiuto di Django lo porterà a riscuotere la taglia che pende sulle loro teste. Il poco ortodosso Schultz assolda Django con la promessa di donargli la libertà una volta catturati i Brittle – vivi o morti. Il successo dell’operazione induce Schultz a liberare Django, i due uomini scelgano di non separarsi, anzi Schultz sceglie di partire alla ricerca dei criminali più ricercati del Sud con Django al suo fianco. Affinando le vitali abilità di cacciatore, Django resta concentrato su un solo obiettivo: trovare e salvare Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), la moglie che aveva perso tempo prima, a causa della sua vendita come schiava. -

Defying Conventions and Highlighting Performance 49

Defying Conventions and Highlighting Performance Within and Beyond Slavery in William Wells Brown's Clotel Eileen Moscoso English Faculty advisor: Lori Leavell As an introduction to his novel, Clotel or, The President's Daughter, William Wells Brown, an African American author and fugitive slave, includes a shortened and revised version of his autobiographical narrative titled “Narrative of the Life and Escape of William Wells Brown” (1853). African American authors in the nineteenth century often feared the skepticism they would undoubtedly receive from white readers. Therefore, in order to broaden their readership and gain a more trusting audience, African American authors routinely sought a more socially accepted and allegedly credible person, namely a white American, to authenticate their writing in the preface. Brown boldly refuses to adhere to this convention in an effort to rid his white readership of their assumptions of black inferiority. Rather, he authorizes himself. My paper illuminates Brown's defiance of authorship conventions as an act of resistance rooted in performance, one that strategically parallels other forms of resistance that take place in his literary representations of the plantation. I argue that all counts of trickery enacted by Brown can be better understood when related to the role CLA Journal 1 (2013) pp. 48-58 Defying Conventions and Highlighting Performance 49 _____________________________________________________________ of performance on the plantation. Quite revolutionarily, William Wells Brown uses his own words in the introduction to validate his authorship rather than relying on a more ostensibly qualified figure's. As bold a move that may be, Brown does so with a layer of trickery that allows it to go potentially undetected by the reader. -

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_December 13, 2006_ I, James Michael Rhyne______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: History It is entitled: Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Wayne K. Durrill_____________ _Christopher Phillips_________ _Wendy Kline__________________ _Linda Przybyszewski__________ Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 By James Michael Rhyne M.A., Western Carolina University, 1997 M-Div., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1989 B.A., Wake Forest University, 1982 Committee Chair: Professor Wayne K. Durrill Abstract Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region By James Michael Rhyne In the late antebellum period, changing economic and social realities fostered conflicts among Kentuckians as tension built over a number of issues, especially the future of slavery. Local clashes matured into widespread, violent confrontations during the Civil War, as an ugly guerrilla war raged through much of the state. Additionally, African Americans engaged in a wartime contest over the meaning of freedom. Nowhere were these interconnected conflicts more clearly evidenced than in the Bluegrass Region. Though Kentucky had never seceded, the Freedmen’s Bureau established a branch in the Commonwealth after the war. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

True Detective Episode Guide Episodes 001–024

True Detective Episode Guide Episodes 001–024 Last episode aired Sunday February 24, 2019 www.hbo.com c c 2019 www.tv.com c 2019 www.hbo.com c 2019 www.tvrage.com c 2019 celebdirtylaundry.com c 2019 www.refinery29.com The summaries and recaps of all the True Detective episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http:// www.hbo.com and http://www.tvrage.com and http://celebdirtylaundry.com and http://www.refinery29.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ! This booklet was LATEXed on February 26, 2019 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.61 Contents Season 1 1 1 The Long Bright Dark . .3 2 Seeing Things . .7 3 The Locked Room . 11 4 Who Goes There . 15 5 The Secret Fate of All Life . 19 6 Haunted Houses . 23 7 After You’ve Gone . 27 8 Form and Void . 31 Season 2 35 1 The Western Book of the Dead . 37 2 Night Finds You . 41 3 Maybe Tomorrow . 43 4 Down Will Come . 47 5 Other Lives . 51 6 Church in Ruins . 53 7 Black Maps and Motel Rooms . 55 8 Omega Station . 59 Season 3 63 1 The Great War and Modern Memory . 65 2 Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye . 67 3 The Big Never . 69 4 The Hour and the Day . 71 5 If You Have Ghosts . 75 6 Hunters in the Dark . 77 7 The Final Country . 79 8 Now Am Found . 81 Actor Appearances 85 True Detective Episode Guide II Season One True Detective Episode Guide The Long Bright Dark Season 1 Episode Number: 1 Season Episode: 1 Originally aired: Sunday January 12, 2014 Writer: Nic Pizzolatto Director: Cary Joji Fukunaga Show Stars: Woody Harrelson (Martin Hart), Matthew McConaughey (Rustin Cohle), Michelle Monaghan (Maggie Hart), Michael Potts (Det. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Why Hip-Hop Is Queer: Using Queer Theory to Examine Identity Formation in Rap Music

Why Hip-Hop is Queer: Using Queer Theory to Examine Identity Formation in Rap Music Silvia Maria Galis-Menendez Advisor: Dr. Irene Mata Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies May 2013 © Silvia Maria Galis-Menendez 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 “These Are the Breaks:” Flow, Layering, Rupture, and the History of Hip-Hop 6 Hip-Hop Identity Interventions and My Project 12 “When Hip-Hop Lost Its Way, He Added a Fifth Element – Knowledge” 18 Chapter 1. “Baby I Ride with My Mic in My Bra:” Nicki Minaj, Azealia Banks and the Black Female Body as Resistance 23 “Super Bass:” Black Sexual Politics and Romantic Relationships in the Works of Nicki Minaj and Azealia Banks 28 “Hey, I’m the Liquorice Bitch:” Challenging Dominant Representations of the Black Female Body 39 Fierce: Affirmation and Appropriation of Queer Black and Latin@ Cultures 43 Chapter 2. “Vamo a Vence:” Las Krudas, Feminist Activism, and Hip-Hop Identities across Borders 50 El Hip-Hop Cubano 53 Las Krudas and Queer Cuban Feminist Activism 57 Chapter 3. Coming Out and Keepin’ It Real: Frank Ocean, Big Freedia, and Hip- Hop Performances 69 Big Freedia, Queen Diva: Twerking, Positionality, and Challenging the Gaze 79 Conclusion 88 Bibliography 95 3 Introduction In 1987 Onika Tanya Maraj immigrated to Queens, New York City from her native Trinidad and Tobago with her family. Maraj attended a performing arts high school in New York City and pursued an acting career. In addition to acting, Maraj had an interest in singing and rapping. -

Something Akin to Freedom

ሃሁሂ INTRODUCTION I can see that my choices were never truly mine alone—and that that is how it should be, that to assert otherwise is to chase after a sorry sort of freedom. —Barack Obama, Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance n an early passage in Toni Morrison’s second novel, Sula (1973), Nel Iand Sula, two young black girls, are accosted by four Irish boys. This confrontation follows weeks in which the girls alter their route home in order to avoid the threatening boys. Although the boys once caught Nel and “pushed her from hand to hand,” they eventually “grew tired of her helpless face” (54) and let her go. Nel’s release only amplifies the boys’ power as she becomes a victim awaiting future attack. Nel and Sula must be ever vigilant as they change their routines to avoid a confrontation. For the boys, Nel and Sula are playthings, but for the girls, the threat posed by a chance encounter restructures their lives. All power is held by the white boys; all fear lies with the vulnerable girls. But one day Sula declares that they should “go on home the short- est way,” and the boys, “[s]potting their prey,” move in to attack. The boys are twice their number, stronger, faster, and white. They smile as they approach; this will not be a fi ght, but a rout—that is, until Sula changes everything: Sula squatted down in the dirt road and put everything down on the ground: her lunch pail, her reader, her mittens, and her slate. -

The Excessive Present of Abolition: the Afterlife of Slavery in Law, Literature, and Performance

iii The Excessive Present of Abolition: The Afterlife of Slavery in Law, Literature, and Performance A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Jesse Aaron Goldberg May 2018 iv © 2018 Jesse Aaron Goldberg v THE EXCESSIVE PRESENT OF ABOLITION: THE AFTERLIFE OF SLAVERY IN LAW, LITERATURE, AND PERFORMANCE Jesse Aaron Goldberg, Ph.D. Cornell University The Excessive Present of Abolition reframes timescales of black radical imaginaries, arguing that Black Atlantic literary and performative texts and traditions resist periodization into past, present, and future. Their temporalities create an excessive present, in which the past persists alongside a future that emerges concurrently through forms of daily practice. I intervene in debates in black studies scholarship between a pessimistic view that points backward, arguing that blackness is marked by social death, and an optimistic view that points forward, insisting that blackness exceeds slavery’s reach. Holding both views in tension, I illuminate the “excess” that undermines this binary. The law’s violence in its rendering of black bodies as fungible exceeds its capacity for justice, and yet blackness exceeds the reach of the law, never reducible to only the state of abjection conjured by the structuring power of white supremacy. I theorize the excessive present through literature and performance in contrast to legal discourse – notably the 1783 British case Gregson v Gilbert, which is striking because it records a massacre of 131 people as an insurance case, not a murder case. The 1781 Zong Massacre recurs through each of my chapters, via J.M.W. -

Interracial Sex and Intimacy in Contemporary Neo-Slave Narratives

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2005 (Un)conventional coupling: Interracial sex and intimacy in contemporary neo-slave narratives Colleen Doyle Worrell College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Worrell, Colleen Doyle, "(Un)conventional coupling: Interracial sex and intimacy in contemporary neo-slave narratives" (2005). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623470. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-y5ya-v603 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (UN)CONVENTIONAL COUPLING Interracial Sex and Intimacy in Contemporary Neo-Slave Narratives A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Colleen Doyle Worrell 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy CIvtuJiVjL-1 Colleen Doyle Worrell Approved by the Committee, April 2005 Leisa D. Meyer, Cd-Chalr ss, Co-Chair {Ul LI-m j y Kimberly Rae Connor University of San Francisco 11 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner.