University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIRECTOR's REPORT September 20, 2018 FIGHTING COMMUNITY

DIRECTOR’S REPORT September 20, 2018 FIGHTING COMMUNITY DEFICITS On July 10th, OLBPD hosted its annual Family Fun and Learning Day in Cleveland at the Lake Shore Facility. OLBPD hosted 85 registered patrons who enjoyed tours of the Sensory Garden and OLBPD, as well as guest speakers Tracy Grimm from the SLO Talking Book Program, and Beverly Cain, State Librarian of Ohio. OLBPD patrons also enjoyed listening to keynote speaker Romona Robinson, WOIO-TV evening news anchor and author of “A Dirt Road to Somewhere,” and Pam Davenport, Network Consultant from the National Library Service. Exhibitors were also on hand from the Cleveland Sight Center, Guiding Eyes for the Blind, Magnifiers and More, and others offering products and services of interest to our patrons. FORMING COMMUNITIES OF LEARNING Summer Reading Club The 2018 Summer Lit League (SLL), formerly known as Summer Reading Club provided reading and engagement activities that were thematically aligned with Yinka Shonibare’s art installation The American Library. The exhibit in Brett Hall was a part of FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art, a regional art show held in Cleveland, Oberlin and Akron. Key aspects of the collaborative exhibition include international cultural diversity, immigration and the ever- changing political climate of an American City. As it relates to summer programming, the key aspects FRONT built the programmatic foundation of the SLL programmatic experience. Programming content focused on world art and culture activities. Throughout the summer program, participants participated in a variety of enrichment activities that promoted the arts, inclusion, community building, reading, writing and other forms of creative expression. -

Case Western's Alumni Letter Opening Editorial

summer 2010 • vol. 22 • no. 2 DANIEL R. WARmington ’85 (1897/1898) * FRANK H. NEFF ’87 (1898/1899) * James T. PARDee ’88 (1899/1900) * PeRRY L. Hobbs ’86 (1900/1901) * HENRY L. PAyne ’86 (1901/1902) * FRANK H. CHAMBERlin ’92 (1902/1903) * HeRBERT H. DOW ’88 (1903/1904) * ALBERT W. SMITH ’87 (1904/1905) * ROBERT HOFFman ’93 (1905/1906) * GEORGE A. BICknell ’91(1906/1907) * William S. BIDle ’93 (1907/1908) * CHARLES A. CADWell ’95 (1908/1909) * ARTHUR L. STARk ’89 (1909/1910) * William J. CaRTER ’91 (1910/1911) * HaRRY G. SPRingsteen ’97 (1911/1912) * FRANK E. Hulett ’98 (1912/1913) * ARTHUR E. SPOONER ’86 (1913/1914) * GEORGE A. PEABODy ’02 (1914/1915) * ARTHUR F. BLASER ’05 (1915/1916) * HaRRY F. AFFELDER ’04 (1916/1917) * BERTRAM D. QUARRie ’01 (1917/1918) * SAM W. EMERson ’02 (1918/1919) * RaY KAUFFman ’04 (1919/1920) * WARNER M. SKIFF ’06 (1920/1921) * RalPH H. West ’02 (1921/1922) * HeRBERt C. Hale ’96 (1922/1923) * WilbuR J. WAtson ’98 (1923/1924) * OSCAR L. GAEDe ’08 (1924/1925) * JoHN JESTER, JR. ’08 (1925/1926) * EARL A. ROSENDale ’13 (1926/1927) * EUGENE S. DAvis ’12 (1927/1928) * FRANK KULOW ’06 (1928/1929) * ALBERT M. Higley ’17 (1929/1930) * ALBERT M. BAEHR ’16 (1930/1931) * RalPH L. HARDing ’05 (1931/1932) * SAM W. EMERson ’02 (1932/1933) * CHARLES A. HYDe ’08 (1933/1934) * LESTER S. Bale ’09 (1934/1935) * LESTER S. Bale ’09 (1935/1936) * WilbeRT J. Austin ’88 (1936/1937) * LEE M. Clegg ’18 (1937/1939) * ClaRENCE W. COURtney ’03 (1939/1940) * ELMER L. LINDSETH ’25 (1940/1941) * LEONARD E. -

The HANDS Foundation's Warm Wishes Program a Big Success!

Helping HANDS NOV / DEC 2019 A Publication of the HANDS Foundation HELPING TO ASSIST AND INFORM OLDER ADULTS AND SENIORS IN MEDINA COUNTY FOOD, FRIENDS & WARM WISHES The HANDS Foundation’s Warm Wishes Program a Big Success! A chill is in the air as autumn falls upon us. The changing of the seasons did not bother the approximately 50 seniors who joined us at Lodi Family Center on Saturday, October 26. For the inaugural session of our new Warm Wishes program, HANDS was quite pleased with the turnout. Seniors stopped by for a hot lunch of soups, rolls, and hot chocolate while listening to music played by Mark War- HANDS Foundation Executive Assistant Liz Murphy helping out at the buffet table. rick. Each senior was given a blanket to help stave off the bleak weather, and was pro- vided with an opportunity to fill out a specialized Warm Wish- es senior wish for various items to help with the season. Keep your eyes open over the coming months, as we will be doing our best to bring this program to other commu- nities all around the county! Youngsters from the Cloverleaf Youth Football Cheer Squad with Cloverleaf Youth Cheer Director Kati Kornowski and Cloverleaf Cheer Coach (and HANDS President) Christina Waller. Cloverleaf Cheerleaders stuffing the tote bags with blankets. Visit us on the Web: HANDS-Foundation.org Web: the on us Visit P.O. Box 868 | Brunswick, Ohio | 44212 | Ohio Brunswick, | 868 Box P.O. Happy HANDS Across Medina County Foundation County Medina Across HANDS Thanksgiving and Christmas A PUBLICATION OF THE HANDS FOUNDATION HANDS THE OF PUBLICATION A to Everyone! HELPING HANDS | NOVEMBER / DECEMBER 2019 | PAGE 2 HANDS FOUNDATION Mailing ............... -

Extensions of Remarks

11400 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS May 21, 1990 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS VERONICA REAGAN CARMICAL, charged with a high crime or misdemeanor, either party's logic that he appeared to be ESSAY CONTEST WINNER impeached by a majority of a quorum in the acting at least semi-independently. United States' House of Representatives, The greatest threat to the independence and convicted by the votes of two-thirds or of the American federal judiciary came HON. HAROLD ROGERS more of a quorum in the federal Senate. more than a century after death took John OF KENTUCKY Historically, federal judicial independence Marshall from the Supreme Court in 1835. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES resulted in numerous analyses. Among the In 1937 popular President Franklin D. Roo most notable of these was Number 78 of sevelt, angered because he had been unable Monday, May 21, 1990 "The Federalist Papers," written by Alexan to name even one justice of the Supreme Mr. ROGERS. Mr. Speaker, 200 years ago, der Hamilton. who favored life appoint Court during his first four years in office the Constitution of these United States was in ments for federal judges. Hamilton's only and because holdover jurists from previous its infancy. Our First President, George Wash stated reservation regarding the matter was Republican and Democrat administrations ington, had been in office just a little over a that in case of a judge who was insane or had struck down so many New Deal statutes physically incompetent to hear and rule on deemed necessary by Roosevelt for the year. Our first Congress had only begun to cases before his court. -

Refocus Nov 2019

By Jim Scanlon A REPORT OF THE CLEVELAND STROKE CLUB Nov. 2019 Cleveland Stroke Club, c/o Geri Pitts The MISSION of the Cleveland Stroke Club is 9284 Towpath Trail to enhance the lives of stroke survivors and Seville, OH 44273 their families through support, fellowship and 330-975-4320 socialization, education and advocacy. Next General Meeting Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2019 The Cleveland Stroke Club was founded on the basic self-help concept. That is, stroke survivors and their families banded together to exchange coping techniques for the many stroke-related problems they experience. Except for the months of June and August, our General Meetings are held on the third Wednesdays of each month at Disciples Christian Church at 3663 Mayfield Rd, Cleveland, OH 44121. Usually, we host Bingo at 5:30, dinner at 6:30, and a presentation by community professionals from 7:30 until 8:30. Meetings end at 8:30. In addition, our Caregiver & Survivor meetings are held on the first Wednesday of every month at Select Medical (formerly Kindred Hospital) at 11900 Fairhill Road, Cleveland, OH 44120. We dine together at 6:30 and then breakout into separate meetings for caregivers and survivors from 7:30 until 8:30. Meetings end at 8:30. Please RSVP for both meetings to Kay 440-449-3309 or Deb 440-944-6794. Look for details in this newsletter. If you or a member of your family has had a stroke, we invite you to visit our meetings anytime. New members and community professionals are always welcome. Both meetings have plenty of free handicap parking and are fully wheelchair accessible. -

1024 CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY Minutes of the Regular Board

1024 CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY Minutes of the Regular Board Meeting September 20, 2018 Trustees Room Louis Stokes Wing 12:00 Noon Present: Ms. Butts, Mr. Seifullah, Mr. Corrigan, Ms. Rodriguez, Mr. Hairston Absent: Ms. Washington, Mr. Parker Ms. Rodriguez called the meeting to order at 12:06 p.m. Approval of the Minutes REGULAR BOARD MEETING OF Mr. Corrigan moved approval of the Regular Board Meeting 06/19/18; SPECIAL of 6/19/18 and Special Board Meetings of 6/15/18 & BOARD MEETINGS 8/09/18. Mr. Seifullah seconded the motion, which passed OF 06/15/18 & unanimously by roll call vote. 08/09/18 Approved PRESENTATION: Carnegie West Historic Lamp Replacement Project - Angelo Trivisonno Mr. Trivisonno, resident of Ohio City, stated that the Carnegie West Library was built in 1911 and is one of the original Carnegie libraries. Mr. Trivisonno stated that he was looking at old photographs of Carnegie West dated 1920-1930 and noticed the iron post globe lamps positioned opposite each other atop of the branch’s front entrance stairs. After consulting local blacksmith Gavin Lehman of Cleveland Blacksmithing, it was determined that replicas of these lamps could be fabricated, donated and installed by local artisans. Mr. Trivisonno stated that he wanted to get the Board’s impressions before proceeding. Mr. Corrigan thanked Mr. Trivisonno and stated that this is the sort of neighborhood input about the branches and community involvement that the Library appreciates. In response to Mr. Corrigan’s inquiry, Mr. Trivisonno stated that Mr. Lehman has been in business for about two years. -

1024 CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY Minutes of the Regular Board

1024 CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY Minutes of the Regular Board Meeting September 20, 2018 Trustees Room Louis Stokes Wing 12:00 Noon Present: Ms. Butts, Mr. Seifullah, Mr. Corrigan, Ms. Rodriguez, Mr. Hairston Absent: Ms. Washington, Mr. Parker Ms. Rodriguez called the meeting to order at 12:06 p.m. Approval of the Minutes REGULAR BOARD MEETING OF Mr. Corrigan moved approval of the Regular Board Meeting 06/19/18; SPECIAL of 6/19/18 and Special Board Meetings of 6/15/18 & BOARD MEETINGS 8/09/18. Mr. Seifullah seconded the motion, which passed OF 06/15/18 & unanimously by roll call vote. 08/09/18 Approved PRESENTATION: Carnegie West Historic Lamp Replacement Project - Angelo Trivisonno Mr. Trivisonno, resident of Ohio City, stated that the Carnegie West Library was built in 1911 and is one of the original Carnegie libraries. Mr. Trivisonno stated that he was looking at old photographs of Carnegie West dated 1920-1930 and noticed the iron post globe lamps positioned opposite each other atop of the branch’s front entrance stairs. After consulting local blacksmith Gavin Lehman of Cleveland Blacksmithing, it was determined that replicas of these lamps could be fabricated, donated and installed by local artisans. Mr. Trivisonno stated that he wanted to get the Board’s impressions before proceeding. Mr. Corrigan thanked Mr. Trivisonno and stated that this is the sort of neighborhood input about the branches and community involvement that the Library appreciates. In response to Mr. Corrigan’s inquiry, Mr. Trivisonno stated that Mr. Lehman has been in business for about two years. -

Cleveland Architects Herman Albrecht

Cleveland Landmarks Commission Cleveland Architects Herman Albrecht Birth/Established: March 26, 1885 Death/Disolved: January 9, 1961 Biography: Herman Albrecht worked as a draftsman for the firm of Howell & Thomas. He formed the firm of Albrecht, Wilhelm & Kelly 1918 with Karl Wilhelm of Massillon and John S. Kelly of Cleveland. John Kelly left the firm in 1925 and it was knwon Albrecht & Wilhelm from 1925 until 1933. It was later known Albrecht, Wilhelm, Nosek & Frazen. Herman Albrecht was a native of Massillon. The firm, which maintained offices in both Cleveland and Massillon and was responsible for 700 commissions that are found in Cleveland suburbs of Lakewood, Rocky River, Shaker Heights; and in Massillon, Canton, Alliance, Dover, New Philadelphia, Mansfield, Wooster, Alliance and Warren, Ohio. Albrecht, Wilhelm & Kelly Birth/Established: 1918 Death/Disolved: 1925 Biography: The firm Albrecht, Wilhelm & Kelly was formed in 1918 with Herman Albrecht of Cleveland, Karl Wilhelm of Massillon and John S. Kelly of Cleveland. John Kelly left the firm in 1925 and it was knwon Albrecht & Wilhelm from 1925 until 1933. It was later known Albrecht, Wilhelm, Nosek & Frazen. The firm, which maintained offices in both Cleveland and Massillon. Building List Structure Date Address City State Status Koch Building unk Alliance OH Quinn Residence 1925 Canton OH Standing T.K. Harris Residence 1926 Canton OH Standing William H. Pacell Residence 1919 Alliance OH Standing Meyer Altschuld Birth/Established: 1879 Death/Disolved: unknown Biography: Meyer Altschuld was Polish-born, Yiddish speaking, and came to the United States in 1904. He was active as a Cleveland architect from 1914 to 1951. -

Perry's Victory and International Peace

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Department of the Interior Midwest Archeological Center Lincoln, Nebraska Perry’s Victory and International Peace Memorial, The 1993 Park-wide Archeological Survey of South Bass Island, Ottawa County, Ohio By Rose E. Pennington 2015 Archeological Report 8 PERRY’S VICTORY AND INTERNATIONAL PEACE MEMORIAL, THE 1993 PARK-WIDE ARCHEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF SOUTH BASS ISLAND, OTTAWA COUNTY, OHIO By Rose E. Pennington Archeological Report 8 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Midwest Archeological Center United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Midwest Archeological Center Lincoln, Nebraska 2015 This report has been reviewed against the criteria contained in 43CFR Part 7, Subpart A, Section 7.18 (a) (1) and, upon recommendation of the Midwest Regional Office and the Midwest Archeological Center, has been classified as AVAILABLE Making the report available meets the criteria of 43CFR Part 7, Subpart A, Section 7.18 (a) (1). ABSTRACT During early May, 1993, personnel from the Midwest Archeological Center conducted a park-wide archeological survey of Perry’s Victory and International Peace Memorial (PEVI) on South Bass Island, Ottawa County, Ohio. Much of PEVI’s 10.15 hectares (25.38 acres) rest on a heavily filled and graded tombolo, and a small portion of the park had been surveyed previously. For this reason, the 1993 investigations surveyed only a total of 5.6 hectares (14 acres). The artifact yield was low and much of the project area was found to have been previously disturbed by grading. However, one historic site was discovered. A small test trench was excavated in order to explore a structural foundation uncovered to the northeast of the memorial column. -

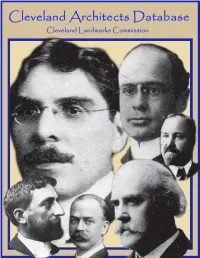

Cleveland Architects Database

Clevland Landmarks Commission Cleveland Architects Database The following is a listing of architects and master builders that have worked in Cleveland, from the 1820’s until the 1930’s. Discovering which architects designed certain buildings was determined by utilizing several sources, including the City of Cleveland Building Permits, and publications that included American Architect and Builder News, Inland Architect, Interstate Architect, the Ohio Architect and Builder, the Annals of Cleveland, the Plain Dealer, the Leader, the Press, Material Facts, the Bystander, and Cleveland Town Topics. The Cleveland Public Library card index for Architect’s in the Fine Arts Department was used. Books on Cleveland Architecture that were consulted included Cleveland Architecture 1876 – 1976, and the American Institute of Architects Guide to Cleveland Architecture were consulted. A catalogue of architectural drawings maintained by the Western Reserve Historical Society was consulted. The Cleveland Necrology file maintained by the Cleveland Public Library, the United States Census, and Cleveland City Directories were consulted in compiling this database. For the purposes of this database an architect was defined as anyone that called himself or herself as an architect. Robert Keiser compiled the Cleveland Architects as a hobby in after work hours over several years. This project terminates with 1930. Local building activity was severely curtailed by the Great Depression, and did not recover until the 1950’s. Many of the references in the database have -

The Ohio Architect and Builder

r ::=====::::=~~ The Ohio Architect and Builder ~\ \ pllbltsbe~ .mont bll? bl? '(tbe \\)btIJ arcbitfct an~ .mlltl~er <!ompanl?, at 180 St. I.!latr St., 'ale"elan~, \\)bto. In tbe tnterests of tbe arcbttects an~ .mlltl~ers of \\) bto a n~ tbe .Mt~Ne 'lIUlest. RATES OF SUBSCRIPTION: TELEPHONES, BUSINESS AND EDITORIAL ROOMS, $1.00 A YEAR IN ADVANCE, MA.IN 7. r\o. 180 ST. CLAIR STREET, TEN CENTS A COPY. CUYAHOGA C ~17~. CLEVELAND, 0 THOMAS A. KNIGHT, Editor. 'October EUGENE MARTINEAU, Bus. Man~ger. F. ~. BARNUM. 2 THE OHIO ARCHITECT· AND BUILDER -------------- EDITORIAL Welcome, Architects WeJ.come, architects, fr·om all over Ameri'ca·! Welcome, delegates of the Ameri can Institute of Ar~hitects, members' and :visitors, to Clevdand, a city which desires the feebly flickering torch of architecture hitherto kept alive 'by a few, to be rekindled into a glowing and enduring flame by your presence. Cleveland as a city ne'eds the educatioti and inspiration which the flower of the architectural 'profession in our leading cities. win bring, Cleveland architects" the local chapter of this organization, and the larger body outside of its definite organization, but in' sympathy with its aims, ne'eds also the stimu~ Ius, the broadening influence that contact with a wider horizon of thought brings, . The profession will and should be 'advanced by the coming of these men, and the learning, ambition, achievement and influence they will emanate, as well as by the. force and value 0.£ their utteranc,e's and deliberations. If the profession be stimulated, then Cleveland as a whole w.ill benefit from the stronger influence toward better things her archi tects will exert. -

Printable Version (PDF)

Cleveland Architects Database The Cleveland Architects Database was envisioned as a comprehensive listing of Cleveland’s rich history of buildings and the architects who designed them. It provides an extensive look at the output of buildings in the careers of Cleveland’s architects to help us further recognize and evaluate their bodies of work, whether well-known or unheralded. A resource for architects, historians, planners, students, and property owners, the Database is a product of the Landmarks Commission’s mandate to conduct a continuous survey of Cleveland’s architectural heritage. The Database covers the history of Cleveland’s built environment, primarily up to the 1940s. It is our intention to expand the Database to include more buildings and architects from the latter half of the twentieth century. And though the focus of the Database is on architects from Cleveland and the work they produced, more entries will be added for architects from elsewhere who designed significant buildings here. The Database went online in June of 2008, and it continues to be updated, corrected, and refined. It is not a finished document, but rather a work in progress that will continue to grow and evolve. We welcome documented additions and corrections. Award In 2014, the Cleveland Restoration Society recognized former Landmarks Commission Secretary Robert Keiser and the Cleveland Architects Database with a Cultural Resource Award at the 2014 Celebration of Preservation. Acknowledgments Robert Keiser, who conducted research for the Commission from 1983 to 2014, and architectural historian Craig Bobby are the primary contributors to its compilation, research, and editing. Additional credit belongs to those who have contributed information over the years or whose research from other projects was incorporated into the Database.