Uhc ^Nbian /Ifoac;A3ine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The M S University of Baroda Doctor of Philosophy Museology

An Analytical Study of Administrative and Curatorial Problems of Government Museums in Gujarat A Thesis submitted to The M S University of Baroda as partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Museology By Dhumal Rashmika Surendra Guided by Dr N R Shah Associate Professor Department of Museology Faculty of Fine Arts The Department of Museology The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Vadodara - 390 002, Gujarat, India 2012 i An Analytical Study of Administrative and Curatorial Problems of Government Museums in Gujarat Ph.D. Thesis Dhumal Rashmika Surendra July 2012 i An Analytical Study of Administrative and Curatorial Problems of Government Museums in Gujarat A thesis submitted to The M S University of Baroda as partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Museology Guide Candidate Dr N R Shah Dhumal Rashmika Surendra Associate Professor Department of Museology The Department of Museology Faculty of Fine Arts The M S University of Baroda Vadodara July 2012 ii An Analytical Study of Administrative and Curatorial Problems of Government Museums in Gujarat A thesis submitted to The M S University of Baroda as partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Museology Guide Candidate Dr N R Shah Dhumal Rashmika Surendra Associate Professor Department of Museology The Department of Museology Faculty of Fine Arts The M S University of Baroda Vadodara July 2012 iii Ph.D. Examination Certificate This is to certify that the content of this thesis is the original research work of the candidate and have at no time been submitted for any other degree or diploma. -

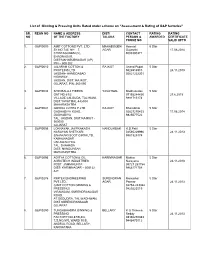

List of Ginning & Pressing Units Rated Under Scheme on “Assessment

List of Ginning & Pressing Units Rated under scheme on “Assessment & Rating of G&P factories” SR. REGN NO NAME & ADDRESS DIST/ CONTACT RATING RATING NO OF THE FACTORY TALUKA PERSON & AWARDED CERTIFICATE PHONE NO VALID UPTO 1. G&P/0009 AMIT COTTONS PVT. LTD MAHABOOBN Hemant 5 Star SY.NO.745, NH – 7, AGAR Gujarathi 17.08.2014 CHINTAGUDEM (V), 9000300371 EHADNAGAR, DIST:MAHABUBNAGAR (AP) PIN – 509 202 2. G&P/0010 JALARAM COTTON & RAJKOT Anand Popat 5 Star PROTEINS LTD 9426914910 24.11.2013 JASDAN- AHMEDABAD 02821222201 HIGHWAY, JASDAN, DIST: RAJKOT, GUJARAT, PIN: 360 050 3. G&P/0034 SHRI BALAJI FIBERS YAVATMAL Madhusudan 5 Star GAT NO:61/2 07153244430 27.6.2015 VILLAGE LALGUDA, TAL:WANI, 9881715174 DIST:YAVATMAL-445304 MAHARASHTRA 4. G&P/0041 GIRIRAJ COTEX P.LTD RAJKOT Bharatbhai 5 Star GADHADIYA ROAD, 02827270453 17.08.2014 GADHADIYA 9825077522 TAL: JASDAN, DIST;RAJKOT - 360050 GUJARAT 5. G&P/0056 LOKNAYAK JAYPRAKASH NANDURBAR R.D.Patil 5 Star NARAYAN SHETKARI 02565229996 24.11.2013 SAHAKARI SOOT GIRNI LTD, 9881925174 KAMALNAGAR UNTAWAD HOL TAL. SHAHADA DIST: NANDURBAR MAHARASHTRA 6. G&P/0096 ADITYA COTTON & OIL KARIMNAGAR Mukka 5 Star AGROTECH INDUSTRIES Narayana 24.11.2013 POST: JAMMIKUNTA 08727 253754 DIST: KARIMNAGAR – 505122 9866171754 A.P. 7. G&P/027 6 RIMTEX ENGINEERING SURENDRAN Manubhai 5 Star PVT.LTD., AGAR Parmar 24.11.2013 (UNIT COTTON GINNING & 02752-243322 PRESSING) 9825223519 VIRAMGAM, SURENDRANAGAR ROAD, AT.DEDUDRA, TAL.WADHWAN, DIST SURENDRANAGAR GUJARAT 8. G&P/0290 TUNGABHADRA GINNING & BELLARY K G Thimma 5 Star PRESSING Reddy 24.11.2013 FACTORY,NO.87/B,3/4, 08392250383 T.S.NO.970, WARD 10 B, 9448470112 ANDRAL ROAD, BELLARY, KARNATAKA 9. -

LOST TIGERS PLUNDERED FORESTS: a Report Tracing the Decline of the Tiger Across the State of Rajasthan (1900 to Present)

LOST TIGERS PLUNDERED FORESTS: A report tracing the decline of the tiger across the state of Rajasthan (1900 to present) By: Priya Singh Supervised by: Dr. G.V. Reddy IFS Citation: Singh, P., Reddy, G.V. (2016) Lost Tigers Plundered Forests: A report tracing the decline of the tiger across the state of Rajasthan (1900 to present). WWF-India, New Delhi. The study and its publication were supported by WWF-India Front cover photograph courtesy: Sandesh Kadur Photograph Details: Photograph of a mural at Garh Palace, Bundi, depicting a tiger hunt from the Shikarburj near Bundi town Design & Layout: Nitisha Mohapatra-WWF-India, 172 B, Lodhi Estate, New Delhi 110003 2 Table of Contents FOREWORD 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 INTRODUCTION 11 STATE CHAPTERS 26 1. Ajmer................................................................................................................28 2. Alwar.................................................................................................................33 3. Banswara...........................................................................................................41 4. Bharatpur..........................................................................................................45 5. Bundi.................................................................................................................51 6. Dholpur.............................................................................................................58 7. Dungarpur.........................................................................................................62 -

Name Capital Salute Type Existed Location/ Successor State Ajaigarh State Ajaygarh (Ajaigarh) 11-Gun Salute State 1765–1949 In

Location/ Name Capital Salute type Existed Successor state Ajaygarh Ajaigarh State 11-gun salute state 1765–1949 India (Ajaigarh) Akkalkot State Ak(k)alkot non-salute state 1708–1948 India Alipura State non-salute state 1757–1950 India Alirajpur State (Ali)Rajpur 11-gun salute state 1437–1948 India Alwar State 15-gun salute state 1296–1949 India Darband/ Summer 18th century– Amb (Tanawal) non-salute state Pakistan capital: Shergarh 1969 Ambliara State non-salute state 1619–1943 India Athgarh non-salute state 1178–1949 India Athmallik State non-salute state 1874–1948 India Aundh (District - Aundh State non-salute state 1699–1948 India Satara) Babariawad non-salute state India Baghal State non-salute state c.1643–1948 India Baghat non-salute state c.1500–1948 India Bahawalpur_(princely_stat Bahawalpur 17-gun salute state 1802–1955 Pakistan e) Balasinor State 9-gun salute state 1758–1948 India Ballabhgarh non-salute, annexed British 1710–1867 India Bamra non-salute state 1545–1948 India Banganapalle State 9-gun salute state 1665–1948 India Bansda State 9-gun salute state 1781–1948 India Banswara State 15-gun salute state 1527–1949 India Bantva Manavadar non-salute state 1733–1947 India Baoni State 11-gun salute state 1784–1948 India Baraundha 9-gun salute state 1549–1950 India Baria State 9-gun salute state 1524–1948 India Baroda State Baroda 21-gun salute state 1721–1949 India Barwani Barwani State (Sidhanagar 11-gun salute state 836–1948 India c.1640) Bashahr non-salute state 1412–1948 India Basoda State non-salute state 1753–1947 India -

Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India 1934-35

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE OF INDIA - 1934 35 . EDITED BY J. F. BLAKISTON, Di;aii>r General of Atchxobgt/ tn Iniia, DELHI: MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS 193T Prici! Rs. Jl-A <n ISt. Gd List of Agents in India from whom Government of India Publications are available. (a) Provinoial Government Book Depots. Madras : —Superintendent, Government Press, Mount Hoad, Madras. Bosibay : —Superintendent, Govommont Printing and Stationorj^ Queen’s Road, Bombay. Sind ; —Manager, Sind Government Book Depot and Record Office, Karachi (Sader). United Provinces : —Superintendent, Government Press, Allahabad. Punjab : —Superintendent, Government Printing, Punjab, Lahore. Central Provinces : —Superintendont, Govommont Printing, Central Provinces, Nagpur. Assam ; —Superintendent, Assam Secretariat Press, Shillong. Bihar : —Superintendent, Government Printing, P. O. Gulzarbagh, Patna. North-West Frontier Province:—Manager, Government Printing and Stationery, Peshawar. Orissa ; —Press Officer, Secretariat, Cuttack. (4) Private Book-seli.ers.' Advani Brothers, P. 0. Box 100, Cawnpore. Malhotra & Co., Post Box No. 94, Lahore, Messrs, XJ, P, Aero Stores, Karachi.* Malik A Sons, Sialkot City. Banthi3’a & Co., Ltd., Station Road, Ajmer. Minerva Book Shop, Anarkali Street, Lahore. Bengal Flying Club, Dum Dum Cantt,* Modem Book Depot, Bazar Road, Sialkot Cantonment Bhawnani & Sons, New Delhi. and Napier Road, JuUtmdor Cantonment. Book Company, Calcutta. Mohanlal Dessabhai Shah, Rajkot. Booklover’s Resort, Taikad, Trivandrum, South India* Nandkishoro k Bros,, Chowk, Bonaros City. “ Burma Book Club, Ltd., Rangoon. Now Book Co. Kitab Mahal ”, 192, Homby Road Bombay. ’ Butterworth &: Co. (India), Ltd., Calcutta. Nowman & Co., Ltd., Calcutta, Messrs. Careers, Mohini Road, Lahore. W. Oxford Book and Stationorj' Company, Delhi, Lahore, Chattorjeo Co., Bacharam Chatterjee Lane, 3, Simla, Meomt and Calcutta. Calcutta. -

Dalal Mott Macdonald

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF TOURISM & CULTURE DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM MARKET RESEARCH DIVISION FINAL REPORT ON 20 YEAR PERSPECTIVE PLAN FOR DEVELOPMENT OF SUSTAINABLE TOURISM IN GUJARAT MARCH 2003 Dalal Mott MacDonald (FORMERLY DALAL CONSULTANTS & ENGINEERS LIMITED) Study Report on Preparation of 20 Years Dalal Mott MacDonald Perspective Plan for Development of Sustainable Joint Director General (MR), in Gujarat Joint Director General (MR), Department of Tourism New Delhi 110011 India Study Report on Preparation of 20 Years Perspective Plan for Development of Sustainable Tourism in Gujarat March 2003 Dalal Mott MacDonald A-20, Sector-2, Noida – 201 301, Uttar Pradesh India 1441//A/10 March 2003 C:\websiteadd\pplan\gujarat\VOLUME 1\Report.doc/ Study Report on Preparation of 20 Years Dalal Mott MacDonald Perspective Plan for Development of Sustainable Joint Director General (MR), in Gujarat Study Report on Preparation of 20 Years Perspective Plan for Development of Sustainable Tourism in Gujarat This document has been prepared for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be relied upon or used for any other project without an independent check being carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Dalal Mott MacDonald being obtained. Dalal Mott MacDonald accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequence of this document being used for a purpose other than the purposes for which it was commissioned. Any person using or relying on the document for such other purpose agrees, and will by such use or reliance be taken to confirm his agreement to indemnify Dalal Mott MacDonald for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. -

General Population Tables, Part II-A, Vol-V

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME V GUJARAT PART II"A GENERAL POPULATION TABLES R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PVllUruED BY mE MAMOU OF l'UBUCA.11O.\'5, tl£11fi PRINTED AT SUllHMH PRrNIERY, ARMroAllAD 1963 PRICE Rs. 5.90 oP. or 13s11. 10d. at $ U.S. 2.13 0.., 0", z '" UJ ! I o ell I I ell " I Ii: o '"... (J) Z o 1-5«0 - (Y: «..., ~ (!) z z CONTENTS PAOD PREFACE iii-iv CENSUS PUBLICATIONS NOTE 3-22 TABLE A-I UNION TABLE A-I Area, Houses and Population 23-36 STATE TABLE A-I Area, Houses and Population of Talukas/Mahals and Towns 37·56 ApPENDIX I 1951 Territorial Units Constituting the present set-up of Gujarat State 57·75 SUB-ApPENDIX Area for 1951 and 1961 for those Municipal Towns which have undergone changes in Area since 1951 Census 76 ApPENDIX II Number of Villages with a Population of 5,000 and over and Towns with a Popu lation under 5,000 77·80 LIST A Places with a Population of under 5,000 treated as Towns for the First Time in 1961 81 LIST B Places with a Population of under 5,000 in 1951 which were treated as Towns in 1951 but have been omitted from the List of Towns in 1961 81 APPENDIX III . Houseless and Institutional Population 82-95 ANNEXURE A Constituent Units of Gujarat State 1901-1941 96-99 ANNEXURE B • Territorial Changes During 1941-1951 100·102 ANNEXURE C Urban Units for which the Area Figures are not separ~tely available 103 TABLE A-n TABLE A-II Variation in Population during sixty years . -

The Indian Army, 3 September 1939

The Indian Army 3 September 1939 Northern Command: HQ Rawalpindi Peshawar District: HQ Peshawar 1st, 7th Companies, The Royal Tank Regiment The Gilgit Scouts: Gilgit Chitral Force: HQ Drosh 1/9th Jat Regiment 1 Company, 1/9th Jat Regiment: Chitral Chitral Mountain Artillery Section, IA 1 Section, 22nd Field Company, Bombay Sappers and Miners Landi Kotal Brigade: HQ Landi Kotal 1st South Wales Borderers 1/1st Punjab Regiment 3/9th Jat Regiment: Bara Fort 4/11th Sikh Regiment 4/15th Punjab Regiment: Shagai 1 Company, 4/15th Punjab Regiment: Ali Masjid 2/5th Royal Gurkha Rifles Detachment, Peshawar District Signals The Kurram Militia: Parachinar Peshawar Brigade: HQ Peshawar 1st King's Regiment 16th Light Cavalry 3/6th Rajputana Rifles 4/8th Punjab Regiment 4/14th Punjab Regiment 2/19th Hyderabad Regiment 8th Anti-Aircraft Battery, RA 19th Medium Battery, RA 24th Mountain Regiment, IA (11th, 16th, 20th Batteries) (1 Battery at Nowshera, 1 Battery at Landi Kotal) (Frontier Posts, IA attached at Landi Kotal, Shagai, Chakdora) 1st Field Company, Bengal Sappers and Miners Peshawar District Signals 18th Mountain Battery, IA - Independent from 1/8/39 from 24th Mountain Regiment Nowshera Brigade: HQ Nowshera 4/5th Mahratta Light Infantry 2/11th Sikh Regiment 10/11th Sikh Regiment 1/6th Gurkha Rifles: Malakand Detachment, 1st South Wales Borderers: Cherat Detachment, 5/12th Frontier Force Regiment: Dargai Detachment, 1/6th Gurkha Rifles: Chakdora 1st Field Regiment, RA (11th, 52nd, 80th, 98th Batteries) 2nd Field Company, Bengal Sappers and Miners -

GIPE-022149.Pdf (6.338Mb)

public £lecWc;K, SMPP^I - GOVERNMENT OF INDIA I.llNISTRY OF WORKS. MINES AND POWER CENTRAL ELECTRICITY COMMISSION PUBLIC ELEGTRIGITY SUPPLY ALL INDIA STATISTICS 1947 PRIOTED IN INDIA FOR THE MANAGFR OF PUBLICATIONS DELHI BY THE MANAGER GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS SIMLA 1949 CONTENTS Foreword iv Reneral Review V—xvU SECTION I—Annual Summary Tables for All-India, Provinces and States 1-10 Details o! Individual undertakings— feECTION II—Provinces 11 Part A—Undertakings in the Provinces generating power at their own stations 12—88 Part B—Undertakings in the Provinces obtaining lulk supplies and distributing power 67-90 SECTION III-Indian States 91 Part A—Undertakings in Indian States generating power at their own stations S2-130 Part B-Undertakings in Indian States obtaining bulk supplies and distributing power 131-138 Index—Alphabetical list of all to'.vns and villages in India havin? an electricity supply with releronces I) the nmler- 139—167 takings serving them. FOREWORD The statistics ielating vO Public Electiicity Supply in India (the Indian Dominion aftei paitition, in• cluding the Hyderabad State i tor the Calendar year 1947 are presented in this volume. During the year under leport, the country was partitioned, as a result ot which a certain number ol undertakings have gone to Pakistan. Since partition, a large number oi States have acceded to the Indian Dominion and cciuJn otliers have been re-grouped or amalgamated with the Indian Dominion. As this process has not re.icbcd a stage ol finality, the States hat^e been arranged rn this book in the same mannei as berore partition. -

District Census Handbook, Sabarkantha, Part XII a & B, Series-7

CENSUS 1991 PARTS XII A & B ,VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY SERIES -7' VILLAGE & TOWNWISE GUJARAT PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT SABARKANTHA DISTRICT DISTRICT CENsus HANDBOOK N. R. VARSANI of the Indian Administrative Service, Director ofCensus Operations, Gujarat -~-~~~~!~!;~;~~~~~~~= .. ________ ... __ ."" ....... _:- 4 _- -_::::;:::.:;:;-; .~-.;. 'Nana Posh ina , area is located in the Khedbrahma Taluka ofSabarkan~ha District. The tribals of this area are known as 'Dungari Bhil'. According to one opinion the term 'Bltil' is derived from th,e.originalDravid term 'BilIu' which means bow or arrow. From ancient times the BIliis are residing in a significant part of the earth, i.e. the hills and so, are keeping with them bows and arrows for self protection. The bows and arrows are life partner oftriba Is, as they are residing in forests infested with wild animals and also as they have to maintain themselves on hunting in dire circumstances. The people of this class frequently came in clash with those ofneighbouring villages. During these skirmishes, they use bows and arrows for attack and for protection. They are adept at this through heriditery process. Women also use bows and arrows. These triba/.{j first laid-foundation ofNeolithic civilisation and these bowmen tribals became the pioneers of the Indian Culture. (Drawing by Shri AA.Saiyad Sr. Draftsman) CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 LIST OF PROPOSED PUBLICATIONS Central Government ~blicaiions - Census of India 1991, Series - 7 Gujarat are being published in the following parts: Part No. Subject Covered I-A -

Text, Power, and Kingship in Medieval Gujarat, C. 1398-1511

TEXT, POWER, AND KINGSHIP IN MEDIEVAL GUJARAT, C. 1398-1511 APARNA KAPADIA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SCHOOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON, 2010 1 ProQuest Number: 10672899 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672899 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract of Thesis Text, Power, and Kingship in Medieval Gujarat, c. 1398 -1511 Despite the growing interest in the region of Gujarat, its pre-colonial history remains a neglected area of research. The dissertation is an attempt at redressing this gap, as well as at developing an understanding of the role of literary culture in the making of local polities in pre-modern South Asia. The dissertation explores the relationship between literary texts and political power. It specifically focuses on the fifteenth century, which coincides with the rise of the regional sultanate, which, along with the sultanates of Malwa, Deccan, and the kingdoms of Mewad and Marwar, emerged as an important power in the politics of South Asia in this period. -

IMPERIAL GAZETTEER of Indli\

THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDli\ VOL. XXVI ATLAS NEW EDITION PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HIS MAJESTY 2 SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INDIA IN c(K~CIL OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS Hr:~R\ l'ROWDE, M t\ LOXDOX, EDI'<BURGII, NEW YORh TORC''iTO ,\XD \IU nOlJl<.i'lF ... PREFACE This Atlas has been prepared to accompany the new edition of The ImjJerzal Gazetteer of India. The ollgmal scheme was planned by Mr. W. S. Meyer, C.I.E., when editor for India, in co-operation with Mr. J S. Cotton, the editor in England. Mr. Meyer also drew up the lists of selected places to be inserted in the Provincial maps, which were afterwards verified by Mr. R. Burn, his suc cessor as editor for India. Great part of the materials (especially for the descriptive maps and the town plans) were supplied by the Survey of India and by the depart ments in India concerned. The geological map and that showing economical minerals were specially compiled by Sir Thomas Holland, K.C.I.E. The meteorological maps are based upon those compiled by the late Su' John Eliot, KC.I.E., for his Clzmatological Atlas of Indw The ethno logical map is based upon that compiled by Sir Herbel t Risley, KC.I.E., for the RejJort of tlte Comts of htdza, 1901. The two linguistic maps wele specially compiled by Dr. G. A. Grierson, C.I.E., to exlublt the latest results of the Linguistic Survey of India. The four historical sketch maps-~howing the relative extent of British, 1\1 uham madan, and Hindu power in 1765 (the year of the Dl\v;il1l grant), in 1805 (after Lord Wellesley), in ] 837 (the acces sion of Queen Victoria), and in 1857 (the Mutiny)-~-havc been compiled by the editor In England.