UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Forum

The newsletter for the Education Section of the BSHS No 42 Education February 2004 Forum Edited by Martin Monk 32, Rainville Road, Hammersmith, London W6 9HA Tel: 0207-385-5633. e-mail: [email protected] Contents Editorial 1 Articles - Poems of science: Chaucer’s doctor of physic 1 - Deadening uniformity or liberated pluralism: 5 can we learn from the past? - A tale of two teachers? 8 News Items 12 Forthcoming Events 14 Reviews - Great Physicists: the life and times of leading physicists from Galileo to Hawking 15 - Mercator: the man who mapped the planet 17 - The Lunar Men: the friends who made the future 19 - Gods in the Sky: Astronomy from the ancients to the Renaissance 21 Resources - Wright Brothers and flight 22 - Darwin and Design 22 - How to Win The Nobel Prize 22 - 1 - Editorial Martin Monk I have been helping Kate Buss with the editing for the past year. Now she has asked me to take over. I wish to thank Kate for more than four years of patience and skill in editing Education Forum. I think we all wish her well in the future. So this is the first issue of Education Forum for which I take sole responsibility Tuesday 4th May is the deadline for copy for the next issue of Education Forum. [email protected] Articles Poems of science John Cartwright In this new series John Cartwright takes a poem each issue of Forum and examines its scientific content. With last year’s BBC screening of an updated version of the Canterbury Tales there is more than one reason to start with Chaucer. -

Birmingham 2020 – Think Big, Think BACO

FEATURE Birmingham 2020 – think big, think BACO BY LUCY DALTON When Richard Irving and Ann-Louise McDermott made their successful bid to host BACO 2020 in Birmingham, they knew it had far more going for it than the International Conference Centre! Lucy Dalton tells us a little more about the attractions of England’s second city and interviews the two local organisers. ver thought of England’s growth? Back in the Domesday Book era (geographical) waist as a skinny of 1086, the Manor of Birmingham was no-man’s-land? Well think again: sparsely populated and poor. Valued at 20 EEngland’s midriff is big. Not the ugly, shillings, it would hardly have featured on liposuction-inspiring, blobby fat; rather, that William the Conqueror’s tax-hunting radar. enviable bulky, athletic big that comes with Scattered habitation and gentle waterways years of determination, guts and training. punctuated rolling hills. Enter Peter de Why? Birmingham. Birmingham, new Lord of the Manor. In the Birmingham, UK, is the heavyweight mid-12th century he began holding markets centre of Mid-England. As the UK’s second at his castle, from whence developed a largest city (1.2 million inhabitants), market town. Little did the farmers of the and sistered with cities such as Chicago, time realise that the ring in the ground used Frankfurt, Milan, Johannesburg and for tethering bulls on market days would Changchun, it contends in a league of turn into one of Birmingham’s most iconic its own. Though Spaghetti Junction, a (shopping) landmarks almost a millennium Lucy Dalton convoluted local road network with a later: The Bullring. -

William Blake “The Chimney Sweeper” 1 When My Mother Died I

William Blake “The Chimney Sweeper” 1 “The Chimney Sweeper” 2 When my mother died I was very young. A little black thing among the snow: And my father sold me while yet my tongue Crying weep, weep, in notes of woe! Could scarcely cry “ ‘weep! ‘weep! ‘weep! ‘weep!” Where are thy father & mother? say? So your chimneys I sweep & in soot I sleep. They are both gone up to the church to pray. There’s little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head, Because I was happy upon the heath, That curl’d like a lamb’s back, was shav’d: so I said: And smil’d among the winters snow: “Hush, Tom! never mind it, for when your head’s bare They clothed me in the clothes of death, You know that the soot cannot spoil your white hair.” And taught me to sing the notes of woe. And so he was quiet & that very night, And because I am happy, & dance & sing, As Tom was a-sleeping, he had such a sight! They think they have done me no injury: That thousands of sweepers, Dick, Joe, Ned & Jack, And are gone to praise God & his Priest & King Were all of them lock’d up in coffi ns of black. Who make up a heaven of our misery. And by came an Angel who had a bright key, And he open’d the coffi ns & set them all free; Then down a green plain leaping, laughing, they run, And wash in a river, and shine in the Sun. Then naked & white, all their bags left behind, They rise upon clouds and sport in the wind; And the Angel told Tom, if he’d be a good boy, 1 Songs of Innocence He’d have God for his father & never want joy. -

Mary Shelley: Teaching and Learning Through Frankenstein Theresa M

Forum on Public Policy Mary Shelley: Teaching and Learning through Frankenstein Theresa M. Girard, Adjunct Professor, Central Michigan University Abstract In the writing of Frankenstein, Mary Shelley was able to change the course of women’s learning, forever. Her life started from an elite standpoint as the child of Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin. As such, she was destined to grow to be a major influence in the world. Mary Shelley’s formative years were spent with her father and his many learned friends. Her adult years were spent with her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and their literary friends. It was on the occasion of the Shelleys’ visit to Lord Byron at his summer home that Mary Shelley was to begin her novel which changed the course of women’s ideas about safety and the home. No longer were women to view staying in the home as a means to staying safe and secure. While women always knew that men could be unreliable, Mary Shelley openly acknowledged that fact and provided a forum from which it could be discussed. Furthermore, women learned that they were vulnerable and that, in order to insure their own safety, they could not entirely depend upon men to rescue them; in fact, in some cases, women needed to save themselves from the men in their lives, often with no one to turn to except themselves and other women. There are many instances where this is shown throughout Frankenstein, such as: Justine’s prosecution and execution and Elizabeth’s murder. Mary Shelley educated women in the most fundamental of ways and continues to do so through every reading of Frankenstein. -

The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18Th Century Great Britain

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain Scott H. Zurawel Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Zurawel, Scott H., "The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain" (2011). Honors Theses. 1092. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1092 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i THE LUNAR SOCIETY OF BIRMINGHAM AND THE PRACTICE OF SCIENCE IN 18TH CENTURY GREAT BRITAIN: A STUDY OF JOSPEH PRIESTLEY, JAMES WATT AND WILLIAM WITHERING By Scott Henry Zurawel ******* Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE March, 2011 ii ABSTRACT Zurawel, Scott The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in Eighteenth-Century Great Britain: A Study of Joseph Priestley, James Watt, and William Withering This thesis examines the scientific and technological advancements facilitated by members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham in eighteenth-century Britain. The study relies on a number of primary sources, which range from the regular correspondence of its members to their various published scientific works. The secondary sources used for this project range from comprehensive books about the society as a whole to sources concentrating on particular members. -

British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 12-1-2019 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century Beverley Rilett University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Rilett, Beverley, "British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century" (2019). Zea E-Books. 81. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/81 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. CHARLOTTE SMITH WILLIAM BLAKE WILLIAM WORDSWORTH SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE GEORGE GORDON BYRON PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY JOHN KEATS ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING ALFRED TENNYSON ROBERT BROWNING EMILY BRONTË GEORGE ELIOT MATTHEW ARNOLD GEORGE MEREDITH DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI CHRISTINA ROSSETTI OSCAR WILDE MARY ELIZABETH COLERIDGE ZEA BOOKS LINCOLN, NEBRASKA ISBN 978-1-60962-163-6 DOI 10.32873/UNL.DC.ZEA.1096 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. University of Nebraska —Lincoln Zea Books Lincoln, Nebraska Collection, notes, preface, and biographical sketches copyright © 2017 by Beverly Park Rilett. All poetry and images reproduced in this volume are in the public domain. ISBN: 978-1-60962-163-6 doi 10.32873/unl.dc.zea.1096 Cover image: The Lady of Shalott by John William Waterhouse, 1888 Zea Books are published by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries. -

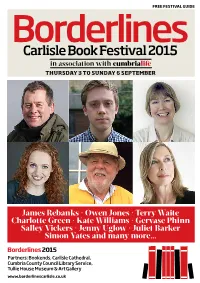

Borderlines 2015

FREE FESTIVAL GUIDE BorderlinesCarlisle Book Festival 2015 in association with cumbrialife THURSDAY 3 TO SUNDAY 6 SEPTEMBER James Rebanks � Owen Jones � Terry Waite Charlotte Green � Kate Williams � Gervase Phinn Salley Vickers � Jenny Uglow � Juliet Barker Simon Yates and many more... Borderlines 2015 Partners: Bookends, Carlisle Cathedral, Cumbria County Council Library Service, Tullie House Museum & Art Gallery www.borderlinescarlisle.co.uk President’s welcome city strolling Rigby Phil Photography The Lanes Carlisle ell done to everyone at The growth in literary festivals in the last image courtesy of BHS Borderlines for making it decade has partly been because the such a resounding reading public, in fact the general public, success, for creating a do like to hear and see real live people for Wliterary festival and making it well and a change, instead of staring at some sort truly a part of the local community, nay, of inanimate box or computer contrap- part of national literary life. It is now so tion. The thing about Borderlines is that well established and embedded that it it is totally locally created and run, a feels as if it has been going for ever, not- for- profit event, from which no one though in fact it only began last year… gets paid. There is a committee of nine yes, only one year ago, so not much to who include representatives from boast about really, but existing- that is an Cumbria County Council, Bookends, achievement in itself. There are now Tullie House and the Cathedral. around 500 annual literary festivals in So keep up the great work. -

Erasmus Darwin - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Erasmus Darwin - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Erasmus Darwin(12 December 1731 – 18 April 1802) Erasmus Darwin was an English physician who turned down George III's invitation to be a physician to the King. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, abolitionist, inventor and poet. His poems included much natural history, including a statement of evolution and the relatedness of all forms of life. He was a member of the Darwin–Wedgwood family, which includes his grandsons Charles Darwin and Francis Galton. Darwin was also a founding member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, a discussion group of pioneering industrialists and natural philosophers. <b>Early Life</b> Born at Elston Hall, Nottinghamshire near Newark-on-Trent, England, the youngest of seven children of Robert Darwin of Elston (12 August 1682–20 November 1754), a lawyer, and his wife Elizabeth Hill (1702–1797). The name Erasmus had been used by a number of his family and derives from his ancestor Erasmus Earle, Common Sergent of England under Oliver Cromwell. His siblings were: Robert Darwin (17 October 1724–4 November 1816) Elizabeth Darwin (15 September 1725–8 April 1800) William Alvey Darwin (3 October 1726–7 October 1783) Anne Darwin (12 November 1727–3 August 1813) Susannah Darwin (10 April 1729–29 September 1789) John Darwin, rector of Elston (28 September 1730–24 May 1805) He was educated at Chesterfield Grammar School, then later at St John's College, Cambridge. He obtained his medical education at the University of Edinburgh Medical School. -

Inseparable Interplay Between Poetry and Picture in Blake's Multimedia Art

PETER HEATH All Text and No Image Makes Blake a Dull Artist: Inseparable Interplay Between Poetry and Picture in Blake's Multimedia Art W.J.T. Mitchell opens his book Blake's Composite Art by saying that “it has become superfluous to argue that Blake's poems need to be read with their accompanying illustrations” (3); in his mind, the fact that Blake's work consists of both text and image is obvious, and he sets out to define when and how the two media function independently of one another. However, an appraisal of prominent anthologies like The Norton Anthology of English Literature and Duncan Wu's Romanticism shows that Mitchell's sentiment is not universal, as these collections display Blake's Songs of Innocence and Experience as primarily poetic texts, and include the illuminated plates for very few of the works.1 These seldom-presented pictorial accompaniments suggests that the visual aspect is secondary; 1 The Longman Anthology of British Literature features more of Blake's illuminations than the Norton and Romanticism, including art for ten of Blake's Songs. It does not include all of the “accompanying illustrations,” however, suggesting that the Longman editors still do not see the images as essential. at the EDGE http://journals.library.mun.ca/ate Volume 1 (2010) 93 clearly anthology editors, who are at least partially responsible for constructing canons for educational institutions, do not agree with Mitchell’s notion that we obviously must (and do) read Blake’s poems and illuminations together. Mitchell rationalizes the segregated study of Blake by suggesting that his “composite art is, to some extent, not an indissoluble unity, but an interaction between two vigorously independent modes of expression” (3), a statement that in fact undoes itself. -

The Last Man"

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2016 Renegotiating the Apocalypse: Mary Shelley’s "The Last Man" Kathryn Joan Darling College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Darling, Kathryn Joan, "Renegotiating the Apocalypse: Mary Shelley’s "The Last Man"" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 908. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/908 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The apocalypse has been written about as many times as it hasn’t taken place, and imagined ever since creation mythologies logically mandated destructive counterparts. Interest in the apocalypse never seems to fade, but what does change is what form that apocalypse is thought to take, and the ever-keen question of what comes after. The most classic Western version of the apocalypse, the millennial Judgement Day based on Revelation – an absolute event encompassing all of humankind – has given way in recent decades to speculation about political dystopias following catastrophic war or ecological disaster, and how the remnants of mankind claw tooth-and-nail for survival in the aftermath. Desolate landscapes populated by cannibals or supernatural creatures produce the awe that sublime imagery, like in the paintings of John Martin, once inspired. The Byronic hero reincarnates in an extreme version as the apocalyptic wanderer trapped in and traversing a ruined world, searching for some solace in the dust. -

Non-Native Plants Add to the British Flora Without Negative Consequences for Native Diversity

This is a repository copy of Non-native plants add to the British flora without negative consequences for native diversity. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/85229/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Thomas, Chris D orcid.org/0000-0003-2822-1334 and Palmer, Georgina orcid.org/0000- 0001-6185-7583 (2015) Non-native plants add to the British flora without negative consequences for native diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 201423995. pp. 4387-4392. ISSN 1091-6490 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1423995112 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Thomas, C. D., & Palmer, G. (2015). Non-native plants add to the British flora without negative consequences for native diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 112 (14), 4387–4392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423995112 AUTHOR FINAL COPY Short title: Non-natives increase floral diversity C D Thomas1* and G Palmer1 Author affiliation: 1Department of Biology, University of York, Wentworth Way, York YO10 5DD, UK * [email protected] Keywords: alien, biodiversity, conservation, invasive species 1 Abstract Plants are commonly listed as invasive species, presuming that they cause harm at both global and regional scales; ~40% of species listed as invasive within Britain are plants. -

Articles Set in Albuquerque and Wolfgang Von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, Ludwig Tieck, Some in Rochester

N E W S De-Faced Blake Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 20, Issue 3, Winter 1986-87, p. 110 PAGE 110 BLAKE/AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY WINTER 1986-87 CALL FOR PLAYS NEWSLETTER Actors Theatre of Louisville is now conducting a nation- wide search for unpublished translations and adapta- tions of plays for next season's (1987-88) Classics in Con- text Festival — "The Romantics," which will celebrate DE-FACED BLAKE the ideals and influence of Romanticism on the stage. Readers may have noticed a certain patchiness in the Though plays by any dramatist whose work is associated type of our fall issue, the unfortunate but unavoidable with Romanticism will be considered, plays byjohann result of having some articles set in Albuquerque and Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, Ludwig Tieck, some in Rochester. The patchiness will continue until all Alexander Pushkin, and Michael Lermontov are of par- articles set in New Mexico have been published, perhaps ticular interest. New plays (either original or adapta- as late as the summer and fall issues next year. tions of novels) that deal with the people, ideas, and events connected with Romanticism will also be con- ERRATA'S ERRATA sidered. Please submit plays by 1 November 1987 to Actors Theatre of Louisville, Literary Department, 316 Our readers might like to note these corrections to "Im- West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. proving the Text of The Complete Poetry & Prose of William Blake' {Blake, fall 1986): Blake p. 50: ENERGY AND THE IMAGINATION p. xvii canterbury should read Canterbury Morton D. Paley would like to purchase a clean, un- *p.