Introduction 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artist Resale Rights Charge Applies to This Lot Lot No Description Estimate Lot No Description Estimate

Lot No Description Estimate Lot No Description Estimate 1 A quantity of electroplated flatware and £40-£60 14 A cased set of six silver teaspoons and £40-£60 table ware, including a pair of casters, tongs with Apostle finials, Sheffield milk and sugar pair, etc. (box) 1915, to/w a pair of epns sauce boats and various electroplated flatware, etc. 2 A quantity of silver and electroplated £80-£120 (box) flatware - some cased - to/w table wares including divided serving dish 15 Twelve various Georgian and Victorian £80-£120 with ebonised handle, bottle coasters, silver teaspoons and other small sugar basin, bachelor teapots, nurse's spoons, to/w a pair of sugar tongs, 9.1 buckles, etc. (box) oz total, a cased three-piece condiment set with blue glass liners, Birmingham 3 A canteen of epns Dubarry flatware and £30-£40 1935 and a cased set of six seal-top cutlery - little used, to/w a cased set of spoons, Sheffield 1937, to/w an silver coffee spoons with tongs, electroplated pint mug and various Sheffield 1914 (2) electroplated flatware, etc. (box) 4 An Indian white metal bowl on three £50-£100 16 A cut glass trinket box with engine- £50-£60 scroll supports, to/w a loaded silver turned silver cover, Deakin & Francis, candlestick, Old Sheffield plate snuffers Birmingham 1911, to/w an extensive tray with snuffer, pair of bottle coasters, part set of epns Hanoverian rat-tail epns fruit basket, candelabra, teawares, flatware, felt cutlery rolls, knives, tray, flatware, conductor's baton, etc. (box) etc. 5 A boxed set of four Sterling cocktail £40-£60 -

Portland Daily Press: September 01,1885

_PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. ESTABLISHED JUNK 23, 1862---VQL. 23. PORTLAND, TUESDAY MORNING, SEPTEMBER 1, 1885. HZredMSfflBO PRICE THREE CENTS. SPECIAL NOTICES. BUSINESS CARDS. AT BANCOR. South Abington, Mass.; John Morrison, THE MVAL YACHTS. upper floor. It was more than half off. lie THE MUSTER. time lie dropped a letter which was not had his saw from a baloon East Corinth, Me.; G. M. Gowell, Orono, manufactured case-knife secured. Two hours afterwards the and had put in his time at odd jobs. He was seen from the vessel to descend rapidly INSURANCE. Herbert G. and hundreds of others. The to Race with Criticisms by Col. Briggs, Eastern Maine and New England Puritan Selected intended to force through the window and Patch, Military and strike the water, and that was the last For the horse the exhibi- down upon a shed roof below. He was Editor of the Boston Clobe. seen or heard of the baloonist. After- Fair. depart prominent theCenesta. jump daring ATTORNEY AT LAW AND SOLICITOR Col. discovered before he had finished his job, wards tlie air ship was fallen in with off the tors are E. L. Norcross, Manchester; New 31.—The following no- York, Aug. however, and was put back into a dungeon ('oast with the ropes which connected the car —OF— AV. S. C. If. Nelson, AVater- tices were sent today to the owners of tlie The brigade camped at Augusta as in W.D. LITTLE & Tilton, Togus; on the lower floor. He had made several with the baloon cut. So we think that Fred CO., Creat of Herds of Choice G. -

Hammer Prices - Including Timed Sale to 1St Srandr10093 Tuesday, 11 December 2018

Hammer Prices - including timed sale to 1st srandr10093 Tuesday, 11 December 2018 Lot No Description 1 A quantity of electroplated flatware and table ware, including a pair of casters, milk and sugar pair, etc. (box) £70.00 2 A quantity of silver and electroplated flatware - some cased - to/w table wares including divided serving dish with ebonised handle, bottle coasters, £80.00 sugar basin, bachelor teapots, nurse's buckles, etc. (box) 3 £45.00 A canteen of epns Dubarry flatware and cutlery - little used, to/w a cased set of silver coffee spoons with tongs, Sheffield 1914 (2) 4 An Indian white metal bowl on three scroll supports, to/w a loaded silver candlestick, Old Sheffield plate snuffers tray with snuffer, pair of bottle £95.00 coasters, epns fruit basket, candelabra, teawares, flatware, conductor's baton, etc. (box) 5 A boxed set of four Sterling cocktail spoons with hollow 'straw' stems, to/w a quantity of Dixons electroplated OEP flatware and a box of bone-handled £10.00 steel knives (mostly unused) 6 A good quality canteen of epns flatware and cutlery (little used) £50.00 8 An Old Sheffield plate sauce tureen and cover on stemmed foot, to/w a Victorian electroplated cruet stand with six cut glass bottles, a plated on copper £85.00 wine jug, pair of chambersticks, etc. (box) 9 £30.00 A pair of silver on copper candelabra and other electroplated wares, including bottle coaster, goblets, silver oddments, flatware, etc. (box) 10 A quantity of Dubarry pattern flatware, four-piece tea/coffee service, etc. (box) £10.00 10a £10.00 A set of six Continental 800 grade cocktail spoons with hollow 'straw' stems, to/w a quantity of foreign 'Pack Fong' electroplated flatware, etc. -

Typologie Hüte

Tuque - Kanada Campain hat - Kanada Newsboy cap - Irland Zylinder - England Deerstalkermütze - England Uschanka - Russland Elechek - Kirgistan In Deutschland kennen wir »Tuque« Es handelt sich um eine weiterent- unter dem einfachen Begriff »Strick- Der Name Newsboy cap sorgt heutzu- Bis 1850 galt der Zylinder als unele- Die Deerstalker-Mütze ist eine im Die Bezeichnung Uschanka (von russ. Der Elechek ist ein unverzichtbares wickelte Form des Stetson, bei dem mütze«. Sie ist eine der ältesten tage für Missverständnisse. Die Kopf- gant und wurde von den höheren Stän- Vereinigten Königreich popularisierte »uschi«, Ohren) weist auf die Möglich- Attribut für jede verheiratete Frau in zwei Flächen an der Krone nach innen bekannten Kopfbedeckungen und wird bedeckung war in den 1910-1920er den allenfalls als Reithut getragen. Jagdmütze mit Augen- und Nacken- keit hin, die am Mützenrand einge- Kirgistan. Er sitzt fest auf dem Kopf gewölbt sind. Der Campain hat wird auch Bonnet genannt, da sie französi- Jahren in der unteren Arbeiterklasse Populär wurde der Zylinderhut erst in schirm sowie Ohrenklappen, die meist nähten, nach oben aufgeschlagenen und bedeckt das Haar vollständig. Sie heute von den Ausbildern des US scher Herkunft ist. weit verbreitet und wurde nicht nur den 1820ern, als er zum Hut des Bür- aus kariertem Stoff besteht. Bekannt Klappen bei großer Kälte zum Schutz tragen ihn im Winter wie im Sommer, Marine Corps getragen und ist aus von Zeitungsjungen, sondern auch gers avancierte, sogar zum Symbol wurde sie als »Detektivmütze« durch von Ohren und Nacken und eventuell denn es ist ihnen untersagt, ohne den verschiedenen Filmen bekannt. von Hafenarbeitern, Stahlarbeitern, des Bürgertums schlechthin. -

Vicki's Australian Slang Dictionary

Australian Slang Dictionary What Makes Australia Great? by @Vintuitive for Vicki Fitch in preparation for awarding the title of “Honorary Aussie” Contents A1 B2 C6 D8 E11 F12 G14 H15 I16 J17 K18 L19 M20 N21 O22 P23 Q24 R25 S26 T29 U31 V32 W33 X34 Y35 Z36 Rhyming Slang 37 Expressions 38 A Aerial ping pong: Australian Rules Football, description usually used derogatorily by Rugby Fans Eg: “”I’m going over Johnno’s to watch the aerial ping pong and knock back a few coldies.” Agro: 1. The state of being angry and aggressive. 2. Name of a well known puppet on a children's program. Eg: “That bloke’s going off like a frog in a sock, he’s fairly agro.” Alice: Alice Springs, a town in Northern Territory. Eg: “We’re heading down to the servo at Alice to fill up the ute.” Amber fluid: Beer. Eg: "Nothin' like some sweet amber fluid in the arvo after some hard yakka.” Akubra: An Australian felt hat with a wide brim. Eg: “It’s as hot as out there today, you might want to grab your sunnies and akubra.” Any tic of the clock: Very soon. Eg: "That barra's back. Any tick of the clock now she's gonna bite.” Ankle biter: Small child, also called a rug rat. Eg: "Barbie at my joint this arvo, ankle biters welcome. Bring a plate.” A over T: to fall over, from "arse over tits", adapted from "head over heels". Eg: “” Apple Eater: A Tasmanian. Also "Apple Islander". Eg: “”An Apple eater, a Crow eater, and a New South Welshman walked into a bar and ordered a pot.” Apples, she'll be apples: Everything will be alright. -

Portland Daily Press: August 01,1882

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. TUESDAY AUGUST 1, 1882. PBICE 3 CENTS. ESTABLISH El) JUNE 23, 1862--VOL.‘KR PORTLAND, MORNING, lSffS&gi2Sggt_| Hi ock Ulnrlitt. MAINE POLITICS. outposts without permission. Cipher dispatches AUGUST 1. XLVnth Session. a officer THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, SUMMER RESORTS. TUESDAY MORNING, Congress-lst EGYPT’S WAR. are forbidden, and staff supervising The following quotations of stock* are received telegrams may stop or alter them. and corrected daily by Woodbury & Moulton (inem PublUhed every day (Sunday, excepted,) by the bers of the Boston Stock Exchange), corner of Mid- of Bluff—The Fi- London, August 1.—The Telegraph has the METEOROLOGICAL. The Game independent SENATE. dlo and Exeh&nge streets: PORTLAND PUBLISH!NIG CO., Closing. LAKE AUBURNSPRINGHOTEL FOR THE NEXT TWENTY-FOUR asco—Fusion Defections and Jealousies following: Ovening. INDICATIONS Washington, July 31. 8% AT 97 Exchange Portland. Ramleh, July 31 (Evening).—A detachment Boston Land. 8% St., NO. HOURS. —Grounds of Republican Assurances, Mr. Hoar with amendments from .flEfcft AUBURN, MAINE. reported searching for Midshipman Dechair was fired WaterPower... 4% 4% Peek a: Eight Dollar, a Year. To mall aubaeilb War Dep’t Office Chief Signal ) Etc. the committee the Senate bill to pre- Flint & Pere Marquette common 24 24 judiciary upon by Arabs outside of Ramleb. The Arabs an Sevan Dollar, a Year, II paid In advance. Officer, Washington, D. C., > j (Correspondence of the Boston Journal.) vent and the Uni- Hartford & Erie 7s.. 54 V* punish.counterfeiting,within The London Times on Turkish fled on tlie approach of the cavalry patrol. A. T. & S. 93% from June to October. -

Domino's Pizza

n il M - MANCHESTER HERALD. Monday. Oct. 12. 1987 t - l Automotlva CMS CMS UoklRg for a BUSINESS & SERVICE DIRECTORY RMUIE RMSIILE Champs: Twins claw Missloniaty: Teen-ager works in India / p a ^ 13 USED CAR? RENAULT Alllancot DATSUN IIW 310 OX. Tigers for the crowr Look to Lyocfc.. 1003, 1004. Excollont 40,000 mllot. Sunroof. » TOYOTA OCmOUA condition, fully Mr- Excollont condition. TIMIOKMaAL ED vlcod. Mutt M il ono. 01500. 646-7407. in the AL / page 18 Tf TOm>F1l04lt« DATSUN 510 mo. Auto CMUCME a m m a p a ' 742-0476. RicH: Billionaires’ ranks nearly double / ^ a g ^ l TIQMCFAMVAN matic tranimifsion, ISSSHI njUFCHMOKH body In good condition, CHILDCoro. RotpentlMo m 6 n t e Carlo-1001. T - nVYVNAMIT excollont 2nd cor, now worm porton for l NAWRitTRiknmeE Top, poYvor tioorina, MCMtV CITATION THOil BUYS WHO brakot, windows, •0 FONO FAINMONT bottory, ond now tmoll cHild In our M .T .8 . Boeliol. tniok S oMppar. M FOfO OftANADA muffltr. Runt sroot. Homo. 20-25 Hours- PAINT Slump romoval. Fioo locks, and trunk. Runt DODGE 1873 Mldos Mo •0 FOND MUfTANO $750 or bott otfor. AAuit /woolc. Days. 644-307A B U IL D E R S Inlorlor and oxtorior otUmalat. Spadai aroat, looks aroat. tor Homo. 19W'. WMIHC MONARCH palnibig. Coll Ibday for a MucH moro. AAutt too. Mini Coll647-0314aftor A A kviirriR Avoiiobio. oontMarationIon teroMody* Automotle<rulM con •OFONTFIMBIK) 5. Atk tor Poul.o 6 4 6 -2 7 8 7 frto otnmalo. Tom or Ed and handiMppad. Atkino S4S00. Coll Joo Hours 2-10. -

Australian Icons

Contents Symbols of Australia 4 Australian icons 5 How do icons represent Australia? 6 Icons of the outback 8 Icons of the military 20 The Red Centre 8 Slouch hats 20 The Royal Flying Doctor Service 9 The ‘rising sun’ badge 21 The School of the Air 9 Simpson and his donkey 21 Icons of the bush 10 Icons of sport 22 Gum trees 10 The Ashes 22 Cork hats 11 The Sherrin football 23 Billies 11 Icons of the backyard 24 Icons of the beach 12 The Hills Rotary Hoist 24 Surf lifesavers 12 The Victa lawnmower 25 Thongs 13 Icons we eat 26 Icons of Indigenous Vegemite 26 Australia 14 Meat pies 27 The rainbow serpent 14 Barbecues 28 Daris 15 Bush foods 29 Dot paintings 16 Rock art 17 GLOSSARY WORDS Icons of colonial Australia 18 When a word is printed in bold, click on it to find its meaning. Ned Kelly’s helmet 18 Cobb & Co coaches 19 Try this! 30 Glossary 31 Index 32 Symbols of Australia Australian icons Symbols of Australia represent Australia and its people. They Icons can be objects, places, stories or organisations that represent our land, governments and stories. Most importantly, are special to people. Australian icons are usually things symbols reflect our shared experiences as Australians. that stand out in our culture as being uniquely Australian. They are symbols that inspire strong feelings of pride for What are symbols? our country. Symbols can take many forms, such as objects, places and events. Some symbols are official, while others are unofficial. -

Download Whole Journal

International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives Internationale Vereinigung der Schall- und audiovisuellen Archive Association Internationale d' Archives Sonores et Audiovisuelles Asociacion Internacional de Archivos 1- Contents c_" __ " ___ -==--='."' ==-'~]- Editorial 2 President's Letter 4 Articles 6 Latvia:The Current Status of Archive and Library Digitisation Andris Vilks, Director of the National Library of Latvia 06 How to Steer an Archive through Neoliberal Waters. .. Questions of Financial Sustainability Exemplified by the Osterreichische Mediathek Rainer Hubert, Osterreichischer Mediathek, Austria 28 A New Species of Sound Archive? Adapting to Survive and Prosper Simon Rooks, Multi-Media Archivist, British Broadcasting Corporation, UK 33 Who Jailed Audio? Richard Green, IASA President, Ottawa, Canada 40 Integrating Av Archival Materials into the Curriculum: The Cave Hill Experience Elizabeth F. Watson Learning Resource Centre Bridgetown, Barbados 45 Recordings in Context:The Place of Ethnomusicology Archives in the 21 st centrury janet Topp-Fargion, British Library, UK 62 Towards Integrated Archives: The Dismarc Project Pekka Gronow, YLE Radio Archives, YleisRadio, Finland 66 VideoActive - Creating Access to Europe's Television Heritage johan Oome, Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, Alexander Hecht, Osterreichischer Rundfunk, Austria and Vassilis Tzouvaras, National Technical University af Athens, Greece 71 Janus Attitude How should a national audiovisual archive handle both past and future? Isabelle Giannattasio, Departement de I'Audiovisuel, Bibliotheque nationa/e de France 78 Preservation of Lithuanian Audiovisual Heritage: Digitisation Initiatives juozas Markauskas, Head: Digitisation Department, DIZI, Lithuania 81 Audiovisual Collection in the Occupation Museum of Latvia Lelde Neimane, Museum of Occupation, Riga, Latvia 86 Tribute 89 Manifestazione 80 anni Carlo Marinelli - 24 November 2007 Giorgina Gilardi, IRTEM, Italy 89 ERRATUM IASA Journal No. -

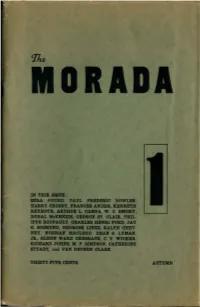

Harry Crosby, Frances Andre, Kenneth Rexroth, Arthur L

IN THIS ISSUE: EZRA POUND, PAUL FREDERIC BOWLES, HARRY CROSBY, FRANCES ANDRE, KENNETH REXROTH, ARTHUR L. CAMPA, W. C. EMORY, DONAL McKENZIE, GEORGE ST. CLAIR, PHIL IPPE SOUPAULT, CHARLES HENRI FORD, JAY G. SIGMUND, GEORGES LINZE, RALPH CHEY NEY, NORMAN MACLEOD, DEAN B. LYMAN, JR., GLENN WARD DRESBACH, C. V. WICKER. RICHARD JOHNS, M. F. SIMPSON, CATHERINE STUART, and VAN DEUSEN CLARK. THIRTY-FIVE CENTS. AUTUMN '( '! I NOTES HARRY CROSBY is an advisory editor of transition. He lives in Paris where, with Caresse Crosby, he edits the Black Sun Press. He has published five volumes of verse, Sonnets For Caresse, Red Skeletons, (illustration by Alastair), Chariot of the Sun (introduction by D. II. Lawrence), Transit of Venus, and Mad Queen and one book of prose, Shadows of the Sun. He has contributed to Blues, transition, Exchange (Paris) and Poetry. PAUL FREDERIC :BOWLES has contributed to transition (12 and 13), Tambour (4) and This Quarter (4). He attended the University of Virginia, lived ·in Paris several months, and hiked through Switzerland and Germany. I He lives in New York. FRANCES ANDRE is a peasant of Luxembourg, who is not a professional writer but a farmer. He has published one slim volume, Peasant Poems. Con tinental critics have hailed him as 01ie of the most authentic forerunners of that proletarian literature which is bound to be realized shortly. KENNETH REXROTH has been published in Blues. IIe lives in San Franeiseo. ARTHUR L. CAMPA is a fellow at the University of New Mexico. He is collect I ing the folk-lore of Nueva Mexico. -

The 2014 University of Cambridge Scavenger Hunt List

The 2014 University of Cambridge Scavenger Hunt List 11 June 2014 TEAMS AND THE RULES OF THE HUNT 1. Disclaimer. In taking part we remind you all that you are adults and responsible for your own actions. We strongly discourage the use of any illegal means for the purposes of acquiring items or completing tasks. This includes making a nuisance of yourselves to the general public. We will also not be impressed by underhand tactics, particularly involving members of other teams. Please remember this is just for fun, there is no need to get carried away and do something you will later regret. 2. Risk Assessment. We do not believe that the activities of the Scavenger Hunt present any significant hazards, require the use of any equipment that requires special safety training, require the use of or result in the production of harmful chemicals, fumes or dust, require you to enter a dangerous or confined space. 3. Control Measures. At all times consider your own safety and that of the public. No Scavenger Hunt items will require you to endanger yourself or any member of the public. If any danger should present itself or an accident should occur, contact the emergency services. If you feel that we have neglected an aspect of your safety, please inform us immediately. 4. Teams. Teams should consist of up to five players. Obviously, there’s not much we can do if you have a small team and lots of friends helping out on individual items. In fact, this is encouraged. However, if any items mention "a team member" or "the entire team", then we’re going to insist on exactly that. -

What Is the Best Way to Begin Learning About Fashion, Trends, and Fashion Designers?

★ What is the best way to begin learning about fashion, trends, and fashion designers? Edit I know a bit, but not much. What are some ways to educate myself when it comes to fashion? Edit Comment • Share (1) • Options Follow Question Promote Question Related Questions • Fashion and Style : Apart from attending formal classes, what are some of the ways for someone interested in fashion designing to learn it as ... (continue) • Fashion and Style : How did the fashion trend of wearing white shoes/sneakers begin? • What's the best way of learning about the business behind the fashion industry? • Fashion and Style : What are the best ways for a new fashion designer to attract customers? • What are good ways to learn more about the fashion industry? More Related Questions Share Question Twitter Facebook LinkedIn Question Stats • Latest activity 11 Mar • This question has 1 monitor with 351833 topic followers. 4627 people have viewed this question. • 39 people are following this question. • 11 Answers Ask to Answer Yolanda Paez Charneco Add Bio • Make Anonymous Add your answer, or answer later. Kathryn Finney, "Oprah of the Internet" . One of the ... (more) 4 votes by Francisco Ceruti, Marie Stein, Unsah Malik, and Natasha Kazachenko Actually celebrities are usually the sign that a trend is nearing it's end and by the time most trends hit magazine like Vogue, they're on the way out. The best way to discover and follow fashion trends is to do one of three things: 1. Order a Subscription to Women's Wear Daily. This is the industry trade paper and has a lot of details on what's happen in fashion from both a trend and business level.