Requiem for a Man with Two First Names by Jesse Raub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December People Band Biographies

December People Band Biographies Robert Berry: Robert Berry was born into a musical family. His father had a dance band that travelled the ballroom circuit in the late 40's and 50's, where his mother was the featured vocalist. When Berry was born his father opened a music store. There, through the busy store’s affiliation with Vox guitars and amps - the brand the Beatles used, Robert was introduced to many of the local musicians. Local hit makers like the Count Five, Syndicate of Sound, Harper’s Bizarre and others often frequented the store. Berry began studying piano in earnest at 6 years old and by age 12 was recruited to join his first rock band with 4 older high school seniors. He continued classical and jazz studies before entering San Jose State University, as a music major. Berry first gained international attention with San Francisco based Hush, and headed to the UK to play in GTR along with Steve Howe of Yes fame, and then achieved a top ten charting single and toured with 3, his partnership with Keith Emerson and Carl Palmer. Before launching December People, Robert played with Sammy Hagar and toured with Ambrosia. When not touring with December People Robert is the bass player with the Greg Kihn Band. Gary Pihl: Raised in the suburbs of Chicago for the first 12 years of his life, Gary Pihl relocated to the San Francisco Bay area. Gary had his recording debut at age 19 with Day Blindness. He says, “After my time in Day Blindness, I was in a band called Fox with Roy Garcia and Johnny V (Vernazza), who went on to play in Elvin Bishop’s band. -

Inyo National Forest Visitor Guide

>>> >>> Inyo National Forest >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> Visitor Guide >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> $1.00 Suggested Donation FRED RICHTER Inspiring Destinations © Inyo National Forest Facts “Inyo” is a Paiute xtending 165 miles Bound ary Peak, South Si er ra, lakes and 1,100 miles of streams Indian word meaning along the California/ White Mountain, and Owens River that provide habitat for golden, ENevada border between Headwaters wildernesses. Devils brook, brown and rainbow trout. “Dwelling Place of Los Angeles and Reno, the Inyo Postpile Nation al Mon ument, Mam moth Mountain Ski Area National Forest, established May ad min is tered by the National Park becomes a sum mer destination for the Great Spirit.” 25, 1907, in cludes over two million Ser vice, is also located within the mountain bike en thu si asts as they acres of pris tine lakes, fragile Inyo Na tion al For est in the Reds ride the chal leng ing Ka mi ka ze Contents Trail from the top of the 11,053-foot mead ows, wind ing streams, rugged Mead ow area west of Mam moth Wildlife 2 Sierra Ne va da peaks and arid Great Lakes. In addition, the Inyo is home high Mam moth Moun tain or one of Basin moun tains. El e va tions range to the tallest peak in the low er 48 the many other trails that transect Wildflowers 3 from 3,900 to 14,494 feet, pro vid states, Mt. Whitney (14,494 feet) the front coun try of the forest. Wilderness 4-5 ing diverse habitats that sup port and is adjacent to the lowest point Sixty-five trailheads provide Regional Map - North 6 vegetation patterns ranging from in North America at Badwater in ac cess to over 1,200 miles of trail Mono Lake 7 semiarid deserts to high al pine Death Val ley Nation al Park (282 in the 1.2 million acres of wil der- meadows. -

265 Edward M. Christian*

COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT ANALYSIS IN MUSIC: KATY PERRY A “DARK HORSE” CANDIDATE TO SPARK CHANGE? Edward M. Christian* ABSTRACT The music industry is at a crossroad. Initial copyright infringement judgments against artists like Katy Perry and Robin Thicke threaten millions of dollars in damages, with the songs at issue sharing only very basic musical similarities or sometimes no similarities at all other than the “feel” of the song. The Second Circuit’s “Lay Listener” test and the Ninth Circuit’s “Total Concept and Feel” test have emerged as the dominating analyses used to determine the similarity between songs, but each have their flaws. I present a new test—a test I call the “Holistic Sliding Scale” test—to better provide for commonsense solutions to these cases so that artists will more confidently be able to write songs stemming from their influences without fear of erroneous lawsuits, while simultaneously being able to ensure that their original works will be adequately protected from instances of true copying. * J.D. Candidate, Rutgers Law School, January 2021. I would like to thank my advisor, Professor John Kettle, for sparking my interest in intellectual property law and for his feedback and guidance while I wrote this Note, and my Senior Notes & Comments Editor, Ernesto Claeyssen, for his suggestions during the drafting process. I would also like to thank my parents and sister for their unending support in all of my endeavors, and my fiancée for her constant love, understanding, and encouragement while I juggled writing this Note, working full time, and attending night classes. 265 266 RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. -

OUTIS the NEWIN Memphis Pride Fest Powered by a 3-DAY GRAND CELEBRATION!

OUTIS THE NEWIN Memphis Pride fest Powered by A 3-DAY GRAND CELEBRATION! FRIDAY, SEPT 23 Saturday, SEPT 24 Sunday, SEPT 25 The Pride Concert Pride Festival Pride Brunch crawl 7p q Handy Park 10a - 5p q Robert Church Park Starts at 1 - 4p in Cooper Young Page 6 Page 12 Page 3 Pride Parade 1 - 2p q Beale Street Page 13 PROUD SPONSOR OF THE LGBT PRIDE PARADE MGM Resorts named one of the “Best Places to Work for LGBT Equality” #GoldStrikeMGM © 2016 MGM Resorts International®. Gambling Problem? Call 1.888.777.9696 Table of contents 4 ........................Welcome to the 13th Annual 15 ..................Performing Artists Memphis Pride Fest The Zoo Girls Midtown Queers 6 ........................Pride Concert Lisa Michaels 7 ........................2016 Grand Marshals 16 ..................Festival Vendors 8 ........................Meet the Board 17 ..................Drum Circle Project 10 ..................2016 Mister & Miss Mid-South Pride OUTMacc Onner IS THE18 ..................Q&A Aubrey Ombre NEW Queer Youth from Playhouse ..................Performing Artists 12 ..................Festival Layout 18 Melanie P. & Mixx Talent ..................Parade Route 13 Mike Hewlett & the Racket 14 ..................Meet Your 2016 Event Hosts ..................After Parties Jaiden Diore Fierce 19 Fannie Mae 20 .................2016IN Sponsors Welcome to the 13th Annual Memphis Pride Fest From your President, Sept 23rd at 7:00pm, followed by the Festival and Parade on I want to welcome you to your 13th Annual Memphis Pride Fest Saturday Sept 24th from 10:00am to 5:00pm with the parade at and Parade with this year’s theme as “OUT is the New IN.” This 1:00pm going down the historic Beale Street, finally we end the year has been an amazing year of growth and expansion for fun-filled weekend with a brunch crawl through Cooper Young The Mid-South Pride Organization. -

Feature Guitar Songbook Series

feature guitar songbook series 1465 Alfred Easy Guitar Play-Along 1484 Beginning Solo Guitar 1504 The Book Series 1480 Boss E-Band Guitar Play-Along 1494 The Decade Series 1464 Easy Guitar Play-Along® Series 1483 Easy Rhythm Guitar Series 1480 Fender G-Dec 3 Play-Along 1497 Giant Guitar Tab Collections 1510 Gig Guides 1495 Guitar Bible Series 1493 Guitar Cheat Sheets 1485 Guitar Chord Songbooks 1494 Guitar Decade Series 1478 Guitar Play-Along DVDs 1511 Guitar Songbooks By Notation 1498 Guitar Tab White Pages 1499 Legendary Guitar Series 1501 Little Black Books 1466 Hal Leonard Guitar Play-Along® 1502 Multiformat Collection 1481 Play Guitar with… 1484 Popular Guitar Hits 1497 Sheet Music 1503 Solo Guitar Library 1500 Tab+: Tab. Tone. Technique 1506 Transcribed Scores 1482 Ultimate Guitar Play-Along Please see the Mixed Folios section of this catalog for more2015 guitar collections. 1464 EASY GUITAR PLAY-ALONG® SERIES The Easy Guitar Play-Along® Series features 9. ROCK streamlined transcriptions of your favorite SONGS FOR songs. Just follow the tab, listen to the CD or BEGINNERS Beautiful Day • Buddy Holly online audio to hear how the guitar should • Everybody Hurts • In sound, and then play along using the back- Bloom • Otherside • The ing tracks. The CD is playable on any CD Rock Show • Use Somebody. player, and is also enhanced to include the Amazing Slowdowner technology so MAC and PC users can adjust the recording to ______00103255 Book/CD Pack .................$14.99 any tempo without changing the pitch! 10. GREEN DAY Basket Case • Boulevard of Broken Dreams • Good 1. -

Eddie Van Halen 1955–2020 Remembering

FEATURE EDDIE VAN HALEN 1955–2020 REMEMBERING Eddie Van Halen passed on 6 October at the age of 65, and the outpouring of emotion from fans and musicians alike only serves to confirm what a unique guitar talent he was. Rock Candy Mag pays tribute to EVH with a heartfelt opinion piece from respected Los Angeles-based critic Bob Lefsetz, a personal appreciation of Eddie’s craft by legendary guitarist Steve Vai, Rock Candy boss Derek Oliver’s insightful recollections of seeing The Great Man in action back in the ’70s, and a technical explanation of Eddie’s abilities from our in-house shredder Oliver Fowler… AND THE CRADLE WILL no longer rock. That’s my ‘1984’ that broke the band wide, I mean to everybody. favourite Van Halen song. It sounds so alive, but Eddie Van Halen isn’t. He paid his dues. You’ve got to be a AND DAVID Lee Roth thought he was the act, but it virtuoso. When no one is watching, no one is paying was always Eddie Van Halen, always. Van Halen could attention, you’re on a mission. continue with a new lead singer, but not without Eddie. Van Halen was one of the very few bands that could AND THEN they started knocking around town. Most succeed at the same level with a new lead singer. That’s bands fermented in their local burb and ultimately pulled testimony to Van Halen’s skills. Sammy Hagar has the up roots and moved to Hollywood. Van Halen started pipes, but look at the venues Hagar’s playing now. -

Van Halen to Tour North America Summer/Fall 2015

VAN HALEN TO TOUR NORTH AMERICA SUMMER/FALL 2015 – VAN HALEN to Perform March 30 on Hollywood Boulevard for Jimmy Kimmel Live in Rare Television Concert Appearance – - Songs from the Concert to Air March 30 and March 31 – LOS ANGELES (March 24, 2015) – In celebration of a 2015 Summer/Fall North American tour, VAN HALEN will perform a special concert for Jimmy Kimmel Live March 30 on Hollywood Boulevard. Featuring some of the band’s essential rock ‘n’ roll classics, the concert will be broadcast over two nights, March 30 and March 31, on the late night talk show and marks VAN HALEN's first U.S. television performance with original lead singer David Lee Roth. Jimmy Kimmel Live airs weeknights at 11:35 p.m. / 10:35 p.m. Central Time on ABC. VAN HALEN is touring North America beginning July 5 in Seattle, Washington at the White River Amphitheatre, with concerts scheduled through Oct. 2 in Los Angeles, California at the legendary Hollywood Bowl. Special guest Kenny Wayne Shepherd Band will support all dates along the tour. Tickets for the Live Nation-promoted tour go on sale beginning April 4 at www.ticketmaster.com and www.livenation.com, with special pre-sale information being announced locally. A complete list of tour dates can be found below. The special Hollywood Boulevard concert will be a hit-heavy set of songs featured on TOKYO DOME LIVE IN CONCERT, the first-ever live album to feature original singer David Lee Roth. Recorded on June 21, 2013 in Tokyo, Japan, TOKYO DOME LIVE IN CONCERT includes 23 songs, spanning all seven of the band’s albums with Roth. -

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. November 30, 2020 to Sun. December 6, 2020 Monday November 30, 2020

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. November 30, 2020 to Sun. December 6, 2020 Monday November 30, 2020 4:00 PM ET / 1:00 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT Final 24 Tom Green Live Keith Moon - On his last night alive, Keith Moon heads to a star-studded party, hosted by his Chris Kattan & Super Dave Osborne - Mirth and monkey business are in store for Tom Green Live friend, Paul McCartney. Surrounded by temptation, he makes an uncharacteristically early with actor/comedian Chris Kattan and hapless daredevil Super Dave Osborne as Tom’s guests. departure from the party, returning home where he takes several handfuls of Hemineverin and falls asleep. Waking up early and disorientated Moon pops more pills and falls asleep again, but 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT this time he won’t wake again. The Very VERY Best of the 70s Crime Movies - From fraud to mobsters, these movies had audiences of the 70s flocking to 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT theaters. Find out which 70s crime movies made our list as Morgan Fairchild, Fred Willard, Anson The Day The Rock Star Died Williams, John Schneider, and more give us their opinions! Keith Moon - Keith Moon was an English drummer for the rock music band The Who. Noted for his unique style, alcohol addiction and his eccentric, often self-destructive behaviour, Moon 7:30 AM ET / 4:30 AM PT developed a reputation for smashing his kit on stage and destroying hotel rooms on tour. His TrunkFest with Eddie Trunk drumming continues to be praised by critics and musicians to this day. -

Agenda Report

Agenda Report October 26, 2020 TO: Honorable Mayor and City Council FROM: City Manager SUBJECT: CONSIDERATION OF LOCAL OPPORTUNITIES TO COMMEMORATE EDWARD L. VAN HALEN RECOMMENDATION: It is recommend that the City Council consider providing direction as to an appropriate means of commemorating Edward L. Van Halen. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: This staff report provides information regarding potential efforts that the City can undertake to recognize and honor Eddie Van Halen, a former Pasadena resident who went on to become one of the all-time greatest guitar players in Rock & Roll history. BACKGROUND: On October 6, 2020, the legendary guitarist Eddie Van Halen succumbed to his battle with throat cancer. Van Halen was the co-founder and main songwriter of the award winning band, Van Halen, a rock group that got its start in Pasadena in the 1970s. Since his passing, the City has received several requests and suggestions from the community to do or name something in Mr. Van Halen's honor to recognize both his local connection to Pasadena, as well as the impact that his artistry had on music. The Van Halen family emigrated from the Netherlands to Pasadena in 1962 and settled in a house on Las Lunas Street. The two Van Halen children, Eddie and Alex, attended Hamilton Elementary School where they performed for the first time in a student band called "The Broken Combs." By the early 1970s, the Van Halen boys attended Pasadena City College where, in a scoring· & arranging class, they met future Van Halen front man David Lee Roth. Together, with Arcadia resident Michael Anthony, they formed the group Van Halen and began playing local venues from backyard parties to the Civic Auditorium. -

2021 Nightclub & Bar Show Announces Newly Added Speakers & Events For

DRAFT RELEASE: June 24, 2021 2021 NIGHTCLUB & BAR SHOW ANNOUNCES NEWLY ADDED SPEAKERS & EVENTS FOR THREE DAY SHOW LAS VEGAS – The 2021 Nightclub & Bar Show is marking its highly anticipated return to Las Vegas next week, and to celebrate the resiliency of the nightlife, restaurant and bar industries, new speakers and exclusive events have been added to the already highly esteemed lineup for this year’s show. Taking place June 28-30, attendees will have the opportunity to hear from notable industry veterans, enjoy experiential classes in the Expo Hall, and mix and mingle with other attendees at various social events. Event Highlights Include: Fireside Chat with Sammy Hagar - ‘Red Rocker’ and Godfather of Celebrity Tequila Tuesday, June 29 at 1:15 p.m. on the NxT Stage Sammy Hagar will return to Nightclub & Bar Show this year for an exclusive one-on-one interview on the NxT Stage to discuss his incredible journey from rock ‘n roll star to philanthropist and godfather of celebrity spirits. One of the most iconic rock stars of all time, Hagar is also an industry entrepreneur with award winning restaurants and spirits under his belt and is the founder of Cabo Wabo Tequila, Sammy’s Beach Bar Rum and Santo Mezquila (the world’s first tequila-mezcal hybrid). Score Big at the Sports Bar Tuesday, June 29 from 12pm-6pm & Wednesday, June 30 from 12pm-5pm on the Expo Hall Floor New for this year, guests are invited to interact with mixologists and industry leaders for an experiential master class hosted by Bob Peters of Innovative Cocktails & Consulting LLC. -

University of Cincinnati

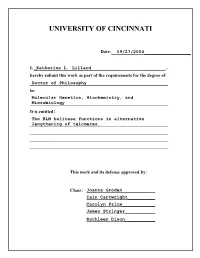

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:__09/27/2004_________________ I, _Katherine L. Lillard___________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: Molecular Genetics, Biochemistry, and Microbiology It is entitled: The BLM helicase functions in alternative lengthening of telomeres. This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Joanna Groden____________ Iain Cartwright__________ Carolyn Price____________ James Stringer___________ Kathleen Dixon___________ THE BLM HELICASE FUNCTIONS IN ALTERNATIVE LENGTHENING OF TELOMERES A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies Of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) In the Department of Molecular Genetics, Biochemistry & Microbiology Of the College of Medicine 2004 by Kate Lillard-Wetherell B.S., University of Texas at Austin, 1998 Committee Chair: Joanna Groden, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Somatic cells from persons with the inherited chromosome breakage syndrome Bloom syndrome (BS) feature excessive chromosome breakage, intra-and inter- chromosomal homologous exchanges and telomeric associations. The gene mutated in BS, BLM, encodes a RecQ-like ATP-dependent 3’-to-5’ helicase that presumably functions in some types of DNA transactions. As the absence of BLM is associated with excessive recombination, in vitro experiments have tested the ability of BLM to suppress recombination and/or resolve recombination intermediates. In vitro, BLM promotes branch migration of Holliday junctions, resolves D-loops and unwinds G-quadruplex DNA. A function for BLM in maintaining telomeres is suggested by the latter, since D- loops and perhaps G-quadruplex structures are thought to be present at telomeres. In the present study, the association of BLM with telomeres was investigated. -

Van Halen – a Different Kind of Truth

Van Halen – A Different Kind Of Truth A Different Kind Of Truth is Van Halen’s twelfth studio album, and their first in fourteen years. This album marks the recording reunion of Eddie and Alex Van Halen with original singer/front man David Lee Roth. Roth was the singer in Van Halen from 1974‐1985, and was replaced by Sammy Hagar when the band softened their hard rock sound into a more commercial pop rock sound in the mid‐1980s. Roth recorded two songs with Van Halen in 1996 for a greatest hits album released when Hagar left the band, and expectations were high that he would return for a new album, but it didn’t work out that way. Instead, Extreme singer Gary Cherone joined Van Halen, and they recorded one weak album together. Touring reunions with both Hagar and Roth followed the departure of Cherone in 1999, but there was no new music recorded. There was much debate whether there would ever be another Van Halen album, as Eddie Van Halen was often seen drunk in public during his separation and after his divorce from actress Valerie Bertinelli. Furthermore, a YouTube video surfaced of Eddie, appearing to be near death, sitting in with a party band playing a Tommy Bolin song, and his guitar playing was pathetic. Eddie appeared unhealthy due to suspected drug use, and the second half of a tour was cancelled in 2008 due to Eddie’s poor health. This is the much abbreviated “CliffsNotes” version of the Van Halen soap opera, which effectively reduced one of the most popular rock bands in history to a joke.