Beware the "Safe" Airplane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Design Study of a Proposed Four-Seat, Amateur-Built Airplane

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2003 A Design Study of a Proposed Four-Seat, Amateur-Built Airplane D. Andrew Moore University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Mechanical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Moore, D. Andrew, "A Design Study of a Proposed Four-Seat, Amateur-Built Airplane. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2003. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2113 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by D. Andrew Moore entitled "A Design Study of a Proposed Four-Seat, Amateur-Built Airplane." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Mechanical Engineering. Dr. Gary Flandro, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Dr. Louis Deken, Dr. Peter Solies Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by D. Andrew Moore entitled “A Design Study of a Proposed Four-Seat, Amateur-Built Airplane.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Mechanical Engineering. -

Stinson Model 108 Series Airplanes

The Stinson 108 Voyager http://www.westin553.net Larry Westin - 01/17/96 UPDATED - REV F - 09/03/14 - Page 1 of 11 As World War II entered its final stages, Stinson decided to use the pre-war model 10 Voyager as the starting point for its first post war airplane. Converting a company owned model 10A Voyager, the first prototype Stinson model Voyager 125 was built in late 1944. Initially this was still a three seater powered by a Lycoming 125 HP engine and known as the Voyager 125. First flight of the postwar Voyager was December 1, 1944. The first prototype (of two) was registered NX31519. First configuration of this airplane shows it with a tail, both vertical and horizontal, similar to the model 10A Voyager. Stinson's new post war aircraft was first named the Voyager 125. It was almost 2 feet longer, 250 pounds heavier and had 35 more horse power than the pre war Voyager. The pre war Voyager 10 was slightly under powered and the additional power was thought adequate to correct this deficiency. Flight tests showed a disappointing performance and the decision was made to use a higher powered engine. Substituting a 150 HP Franklin 6A4-150-B4 created the Voyager 150. The added powered allowed Stinson to make some additional changes by increasing the cabin width, lengthening the fuselage about a foot, and increasing gross weight another 285 pounds, to 2150 pounds. These changes not only improved performance, but it also made the Voyager into a 4 place airplane. The second prototype, registered NX51532, was also a converted model 10A Voyager owned by Stinson. -

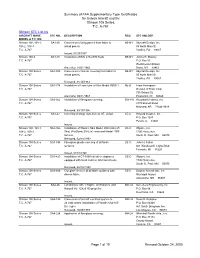

Stinson STC List.Xls AIRCRAFT MAKE STC NO

Summary of FAA Supplementary Type Certificates for Univair Aircraft and the Stinson 108 Series. T.C. A-767 Stinson STC List.xls AIRCRAFT MAKE STC NO. DESCRIPTION REG. STC HOLDER MODEL & T.C. NO. Stinson 108, 108-1, SA1-30 Conversion of wing panels from fabric to NE-NY Skycraft Design, Inc. 108-2, 108-3 alclad panels. 85 North Main St. T.C. A-767 Yardley, PA 19067 Issued, 01/29/1957 Stinson 108-3 SA1-48 Installation of Edo 249-2870 floats. NE-NY James R. Blakely T.C. A-767 P.O. Box 53 Westchester Station Amended, 01/01/1960 Bronx, NY 10461 Stinson 108 Series SA1-258 Conversion of aileron covering from fabric to NE-NY Skycraft Design, Inc. T.C. A-767 alclad panels. 85 North Main St. Yardley, PA 19067 Reissued, 01/14/1983 Stinson 108 Series SA1-374 Installation of Fram lube oil filter Model PB55-1. NE-B Fram Aerospace T.C. A-767 Division of Fram Corp. 750 School St. Amended, 09/11/1967 Pawtucket, RI 02860 Stinson 108 Series SA2-952 Installation of fiberglass covering. SW-FW Razorback Fabrics, Inc. T.C. A-767 2179 Elmont Road Maynard, AR 72444-9688 Reissued, 09/10/1996 Stinson 108 Series SA3-27 Covering of wings .020-inch 24 ST. alclad. CE-C Howard Aviation, Inc T.C. A-767 P.O. Box 1287 Peoria, IL 61601 Issued, Stinson 108, 108-1, SA3-366 Installation of Wipaire Skis Model 3000 (Aircraft CE-C Wipaire, Inc. 108-2, 108-3 Skis) (FluiDyne) (Fli-Lite) main and Model 1000 1700 Henry Ave. -

The Way We Were Part 1 By: Donna Ryan

The Way We Were Part 1 By: Donna Ryan The Early Years – 1954- 1974 Early Years Overview - The idea for the Chapter actually got started in June of 1954, when a group of Convair engineers got together over coffee at the old La Mesa airport. The four were Bjorn Andreasson, Frank Hernandez, Ladislao Pazmany, and Ralph Wilcox. - The group applied for a Chapter Charter which was granted two years later, on October 5, 1956. - Frank Hernandez was Chapter President for the first seven years of the Chapter, ably assisted by Ralph Wilcox as the Vice President. Frank later served as VP as well. The first four first flights of Chapter members occurred in 1955 and 1957. They were: Lloyd Paynter – Corbin; Sam Ursham - Air Chair; Frank Hernandez - Rapier 65; and Waldo Waterman - Aerobile. - A folder in our archives described the October 15-16, 1965 Ramona Fly-in which was sponsored by our chapter. Features: -Flying events: Homebuilts, antiques, replicas, balloon burst competition and spot landing competitions. - John Thorp was the featured speaker. - Aerobatic display provided by John Tucker in a Starduster. - Awards given: Static Display; Safety; Best Workmanship; Balloon Burst; Aircraft Efficiency; Spot Landings. According to an article published in 1997, in 1969 we hosted a fly-In in Ramona that drew 16,000 people. Some Additional Dates, Numbers, Activities June 1954: 7 members. First meeting was held at the old La Mesa Airport. 1958: 34 members. First Fly-in was held at Gillespie Field. 1964: 43 members. Had our first Chapter project: ten PL-2’s were begun by ten Chapter 14 members. -

Rudy Arnold Photo Collection

Rudy Arnold Photo Collection Kristine L. Kaske; revised 2008 by Melissa A. N. Keiser 2003 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Black and White Negatives....................................................................... 4 Series 2: Color Transparencies.............................................................................. 62 Series 3: Glass Plate Negatives............................................................................ 84 Series : Medium-Format Black-and-White and Color Film, circa 1950-1965.......... 93 -

Stinson 108 Buying Considerations by Larry Westin - July 16, 2005 UPDATED - Rev 03 - 10/17/14 - Page 1 of 6

Stinson 108 Buying Considerations http://www.westin553.net By Larry Westin - July 16, 2005 UPDATED - Rev 03 - 10/17/14 - Page 1 of 6 Certain areas should be examined for any airplane you purchase. Such as; airworthiness certificate, aircraft registration, log books, FAA form 337's etc. This article doesn’t include those areas, rather what I want to do here is to emphasize areas of importance specifically to the Stinson 108 series of airplanes. AIRPLANE SERIAL NUMBER Stinson 108's have serial numbers at 5 different locations. The primary serial number for the Stinson 108 is stamped on the steel fuselage frame. Serial numbers are located at the following positions: 1 - The primary airframe serial number is on the copilots side facing the right peddle on the firewall exhaust mount. This number MUST match the serial number on the Data Plate, number 2 below. My thanks to Bob Harper <[email protected]> for checking other Stinson 108's to verify the location of the frame serial number. 2 - Stinson Aircraft Data Plate - this is the official Stinson Division of Consolidated Vultee data plate bolted to the inside of the firewall. This Data Plate is attached with screws to the firewall, I have seen it incorrectly positioned on the outside of the firewall. The serial number on the Data Plate and the serial number stamped on the frame MUST match!! This is important!! 3 - Engine Firewall - stamped just below the top of the firewall on the right side (as viewed from the rear). This should match the serial number on the frame (1 above) and fuselage frame (2 above). -

THE INCOMPLETE GUIDE to AIRFOIL USAGE David Lednicer

THE INCOMPLETE GUIDE TO AIRFOIL USAGE David Lednicer Analytical Methods, Inc. 2133 152nd Ave NE Redmond, WA 98052 [email protected] Conventional Aircraft: Wing Root Airfoil Wing Tip Airfoil 3Xtrim 3X47 Ultra TsAGI R-3 (15.5%) TsAGI R-3 (15.5%) 3Xtrim 3X55 Trener TsAGI R-3 (15.5%) TsAGI R-3 (15.5%) AA 65-2 Canario Clark Y Clark Y AAA Vision NACA 63A415 NACA 63A415 AAI AA-2 Mamba NACA 4412 NACA 4412 AAI RQ-2 Pioneer NACA 4415 NACA 4415 AAI Shadow 200 NACA 4415 NACA 4415 AAI Shadow 400 NACA 4415 ? NACA 4415 ? AAMSA Quail Commander Clark Y Clark Y AAMSA Sparrow Commander Clark Y Clark Y Abaris Golden Arrow NACA 65-215 NACA 65-215 ABC Robin RAF-34 RAF-34 Abe Midget V Goettingen 387 Goettingen 387 Abe Mizet II Goettingen 387 Goettingen 387 Abrams Explorer NACA 23018 NACA 23009 Ace Baby Ace Clark Y mod Clark Y mod Ackland Legend Viken GTO Viken GTO Adam Aircraft A500 NASA LS(1)-0417 NASA LS(1)-0417 Adam Aircraft A700 NASA LS(1)-0417 NASA LS(1)-0417 Addyman S.T.G. Goettingen 436 Goettingen 436 AER Pegaso M 100S NACA 63-618 NACA 63-615 mod AerItalia G222 (C-27) NACA 64A315.2 ? NACA 64A315.2 ? AerItalia/AerMacchi/Embraer AMX ? 12% ? 12% AerMacchi AM-3 NACA 23016 NACA 4412 AerMacchi MB.308 NACA 230?? NACA 230?? AerMacchi MB.314 NACA 230?? NACA 230?? AerMacchi MB.320 NACA 230?? NACA 230?? AerMacchi MB.326 NACA 64A114 NACA 64A212 AerMacchi MB.336 NACA 64A114 NACA 64A212 AerMacchi MB.339 NACA 64A114 NACA 64A212 AerMacchi MC.200 Saetta NACA 23018 NACA 23009 AerMacchi MC.201 NACA 23018 NACA 23009 AerMacchi MC.202 Folgore NACA 23018 NACA 23009 AerMacchi -

VA Vol 18 No 6 June 1990

GHT AND LEVEL f of these people to see if you could be w, "" trying of help. Uto register these ~people" " in advance of A/C Parking & Flight Line Safety Art the fly-in this year. Morgan 414/442-3631 As we will not be having the River A/C Forums John Berendt 507/263 boat Cruise this year (because the boat 2414 has been sold), Steve and Jeannie are Antique Judging Dale Gustafson 3171 planning something special for our AI 293-4430 C Picnic this year. This event will be ,. Classic Judging George York 419/529 held on Sunday night of the conven € 4378 o tion. This is a good opportunity to have ~ A/C Manpower Gloria Beecroft 2131 a good meal without the hassle and the ~ 427-1880 traffic and lines at different restaurants o Q Parade of Flight Phil Coulson 617/624 on this busy night. 6490 Our A/C Parking area is once again by Espie uButchu Joyce Headquarters Staff Kate Morgan 4141 being expanded with the movement of 442-3613 the Ultralight area to west of the air A/C Security Jim Mahoney port. The showplace camping will Q{lJt AlC Press Larry D'Attilio 4141784 have a new portable shower located in It seem possible but soon 0318 the south tree line. Also, we have been it will be time for EAA Oshkosh '90. A/C Maintenance Stan Gomoll 6121 promised that the present showers will It is difficult for a person (unless they 784-1172 be improved. have been involved as a volunteer) to Interview Circle Charles Harris 9181 As you can see, we are working hard imagine how much planning goes into 742-7311 to make your visit to Oshkosh 1990 in putting on this event. -

Lucky Me Lucky Me

LUCKY ME LUCKY ME The Life and Flights of Veteran Aviator CLAY LACY STACY T. GEERE Copyright© 2010 by Clay Lacy 7435 Valjean Avenue Van Nuys, CA 91406 All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work in any form whatsoever without permission in writing from the publishers, except for brief passages in connection with a review. For information, please write: The Donning Company Publishers 184 Business Park Drive, Suite 206 Virginia Beach, VA 23462 Ron Talley, Graphic Designer Clarice Kirkpatrick, Photo Research Coordinator Andrew Wiegert, Clay Lacy Aviation Media Services Melanie Panneton, Executive Assistant to Clay Lacy Marjory D. Lyons, PhD, and Michael Je!erson, Contributing Interview Writers Dwight Tompkins, Publisher’s Representative Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Geere, Stacy T., 1967- Lucky me : the life and "ights of veteran aviator Clay Lacy / Stacy T. Geere. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-57864-635-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Lacy, Clay, 1932- 2. Air pilots--United States--Biography. I. Title. TL540.L2195G44 2010 629.13092--dc22 [B] 2010020410 !is book is dedicated to past, present, and future aviation pioneers and to all who possess an insatiable passion for flight. May your stories travel through time for the enjoyment of generations to come. CONTENTS 15 31 47 61 79 Log Book Entry One: Log Book Entry Two: Log Book Entry Three: Log Book Entry Four: Log Book Entry Five: Six Hours at the Kansas Skies to Global Skies Guppy and Friends Dawn of the Learjet Come Fly With Me Grocery Store Stories shared by Stories shared by Stories shared by Stories shared by Stories shared by Barron Hilton Col. -

Current Stinson ARF Booklet.Qxd

Introduced in 1947, The Stinson 108 Flying Station Wagon was ahead of its time. The slo- gans "My airplane works for a living" and "America's No. 1 Utility Plane" was easy to understand as the Flying Station Wagon seated four along with 100 pounds cargo, and cruised at 130mph. With Carl Goldberg's Stinson 108 ARF Flying Station Wagon you'll experience this classy air- plane like never before. Relaxing predictable slow flight is like second nature. Flaps with duel servo control allow for extremely slow flight & easy landings. When you want something extra, this capa- ble aerobatic beauty features dual elevator servos, independent aileron servos, and airfoiled tail group to take advantage of all your skill. WARNING A radio-controlled model is not a toy and is not intended for persons under 16 years old. Keep this kit out of the reach of younger children, as it contains parts that could be dangerous. A radio- controlled model is capable of causing serious bodily injury and property damage. It is the buyer's responsibility to assemble this aircraft correctly and to properly install the motor, radio, and all other equipment. Test and fly the finished model only in the presence and with the assistance of another experienced R/C flyer. The model must always be operated and flown using great care and common sense, as well as in accordance with the Safety Code of the Academy of Model Aeronautics (5151 Memorial Drive, Muncie, IN 47302, 1-800-435-9262). We suggest you join the AMA and become prop- erly insured prior to flying this model. -

Name of Plan S .E. 5A S E 5 S E 5 a S E 5 a S E V Custom Rat

WING RUBBE ENGIN REDUCED DETAILS NAME OF PLAN SPAN SOURCE Price AMA POND RC FF CL OT SCALE GAS R ELECTRIC OTHER GLIDER 3 VIEW E OT DAVID BODDINGTON S .E. 5A 33” $ 8 12214 X X X RD432 S E 5 $ - 35008 X AIR DESIGN PLAN S E 5 A 80 $ 42 50025 X X X AVIATION MODELLER INT., S E 5 A 54 12-05 $ 25 50471 X X S E V CUSTOM RAT MODEL AIRPLANE NEWS 62F1 24 $ 4 33023 X X RACER 9/57, SEV SPECIAL TEAM LE MODELE REDUIT D'AVION 19A1 S F C A LIGNEL 20 33 $ 4 33461 X X X FLYING ACES CLUB 1/78, LE 22C5 S F C A TAUPIN 13 $ 3 22347 X X RANDEM X FLUG & MODELE TECHNIK S G 38 55 10/83 $ 15 16803 FLYING T MODEL CO. 85E3 S I A 7 B 22 $ 4 33274 X X X A SAMM PLAN, CONOVER 70E4 S I G CUB 24 $ 5 33084 X X AEROMODELLER PLANS, 82G4 S T O L 48 RUSSELL $ 20 33252 X X FLYING MODELS 3/56, 54E6 S Z Y P 8 $ 3 26257 X BURAGAS X VINTAGE AERO PLAN S. E. 5 26” $ 7 15785 X X PRESERVATION OF S. E. 5A 20” ANTIQUE SCALE FLYING $ 4 12626 X X MODEL AIRPLANE PLANS X STERLING KIT PLAN S. E. 5A 40” $ 24 15780 X X X BY JOHN BERRYMAN 95E7 S..A.I. 207 13 $ 4 35959 X X AEROMODELLER 5/83 ABY S.E.5 48/48 MJ HEALY $ 19 11549 X X X Sport Glider, a simple job that S’Neat 73 can be flown with or without Sep-75 $ 9 112 X X X i Scale model of Grumman S2F Tracker: 39 design. -

Civil Aircraft Registers of Honduras

CIVIL AIRCRAFT REGISTERS OF HONDURAS PREFACE; The information shown here is from official reports, production histories, and sightings around the world. To show maximum respect to the Honduran Authorities names, addresses details of private owners are only included where this information has been submitted to BV or similar. Where names of airlines or operators are shown it is where the aircraft has been marked and/or operated with titles, which are in effect in the public domain by their existence. The aim of this project is to encourage interest in the history of aviation in Honduras and to develop a good relationship with the relevant authorities. I hope the presentation of this material will be taken in the positive spirit it is intended. Any observations, additions, and corrections are very welcome to: [email protected] ORIGINAL REGISTRATION SERIES XH-AC1 CESSNA 170B 25107 EX N8255A REG 1952 REG TO CX -09-1956 CX TO XH-101(2) XH-ANA DOUGLAS C-47A- 13301 EX PJ-ALI NB:(INITIALLY XH-T001) 25-DK REG -09-1950 REG TO CX -02-1961 CX TO HR-ANA XH-ANB DOUGLAS C-47-DL 9146 EX XH-T002 REG 26-06-50 REG TO ANHSA CX -02-1961 CX TO HR-ANB XH-ANC DOUGLAS C-47B 16819/ EX N2700A 33567 REG -03-1955 REG TO CX -01-1959 CX TO XH-SAI(2) XH-ASA PIPER PA-18 18-1855 EX N2133A SUPER CUB REG -03-1959 REG TO CX -06-1959 XH-ASB CESSNA 180 30752 EX N2452C REG REG TO CX -02-1961 CX TO HR-ASB XH-ASC CESSNA 170B 26306 EX XH-KVT REG -08-1960 REG TO CX -02-1961 CX TO HR-ASC XH-ASD CESSNA 180 30056 EX XH-145 REG REG TO CX -02-1961 CX TO HR-ASD XH-ASI CESSNA 180A 50308