Looking Back

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Satyajit Ray

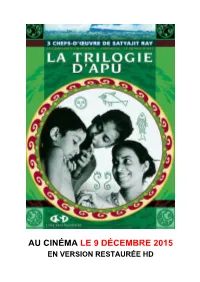

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray. -

Appellate Jurisdiction

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Friday, 12th of February, 2021 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HON'BLE CHIEF JUSTICE THOTTATHIL B. 1 On 12-02-2021 1 RADHAKRISHNAN 1 DB -I At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJESH BINDAL 16 On 12-02-2021 2 17 HON'BLE JUSTICE ANIRUDDHA ROY DB - II At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 12-02-2021 3 32 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBHASIS DASGUPTA DB - III At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 37 On 12-02-2021 4 33 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBHASIS DASGUPTA DB - III At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 2 On 12-02-2021 5 34 HON'BLE JUSTICE KAUSIK CHANDA DB- IV At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 12-02-2021 6 45 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAVI KRISHAN KAPUR DB At 01:00 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 12-02-2021 7 46 HON'BLE JUSTICE SAUGATA BHATTACHARYYA DB-V At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 11 On 12-02-2021 8 48 HON'BLE JUSTICE HIRANMAY BHATTACHARYYA DB - VI At 10:45 AM 11 On 12-02-2021 9 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 54 SB At 02:00 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 28 On 12-02-2021 10 58 HON'BLE JUSTICE TIRTHANKAR GHOSH DB - VII At 10:45 AM 28 On 12-02-2021 11 HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 75 SB - I At 03:00 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 4 On 12-02-2021 12 78 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUVRA GHOSH DB - VIII At 10:45 AM 4 On 12-02-2021 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 82 SB - II At 03:00 PM 38 On 12-02-2021 14 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE 86 SB At 10:45 AM 9 On 12-02-2021 15 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 111 SB - II At 10:45 AM 13 On 12-02-2021 16 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 116 SB - III At 10:45 AM 8 On 12-02-2021 17 HON'BLE JUSTICE SABYASACHI BHATTACHARYYA 126 SB - IV At 10:45 AM SL NO. -

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity DARIUS COOPER San Diego Mesa College PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written perrnission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt. System QuarkXpress® [mg] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cooper, Darius, 1949– The cinema of Satyajit Ray : between tradition and modernity / Darius Cooper p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in film) Filmography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 62026 0 (hb). – isbn 0 521 62980 2 (pb) 1. Ray, Satyajit, 1921–1992 – Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series pn1998.3.r4c88 1999 791.43´0233´092 – dc21 99–24768 cip isbn 0 521 62026 0 hardback isbn 0 521 62980 2 paperback Contents List of Illustrations page ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Between Wonder, Intuition, and Suggestion: Rasa in Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy and Jalsaghar 15 Rasa Theory: An Overview 15 The Excellence Implicit in the Classical Aesthetic Form of Rasa: Three Principles 24 Rasa in Pather Panchali (1955) 26 Rasa in Aparajito (1956) 40 Rasa in Apur Sansar (1959) 50 Jalsaghar (1958): A Critical Evaluation Rendered through Rasa 64 Concluding Remarks 72 2. -

Hold Your Story

HOLD YOUR STORY HOLD YOUR STORY REFLECTIONS ON THE NEWS OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA Edited by Chindu Sreedharan, Einar Thorsen and Asavari Singh Hold your story: reflections on the news of sexual violence in India Edited by Chindu Sreedharan, Einar Thorsen, and Asavari Singh For enquiries, please contact Chindu Sreedharan Email: [email protected] First published by the Centre for the Study of Conflict, Emotion & Social Justice, Bournemouth University https://www.bournemouth.ac.uk/research/centres-institutes/centre-study- conflict-emotion-social-justice ISBN: 978-1-910042-28-1 [print/softcover] ISBN: 978-1-910042-29-8 [ebook-PDF] ISBN: 978-1-910042-30-4 [ebook-epub] BIC Subject Classification Codes: GTC / JFD / KNT/ 1FKA /JFFE2 CC-BY 4.0 Chindu Sreedharan, Einar Thorsen, and Asavari Singh Individual chapters CC-BY 4.0 Contributors Cover design: Create Cluster Editoral coordinator: Shivani Agarwal Printed in India CONTENTS Acknowledgements ix Foreword 1 Ammu Joseph Introduction 6 Chindu Sreedharan, Einar Thorsen, and Asavari Singh PART I MEDIA ETHICS AND RESPONSIBILITIES 1. The recipe for irresponsible coverage 17 Sourya Reddy 2. Just ‘facts’ are not enough 24 Tejaswini Srihari 3. When numbers become ‘just’ numbers 30 Anunaya Rajhans 4. What journalists owe survivors 36 ‘Anitha’, interviewed by Tasmin Kurien 5. Towards undoing silences 46 Urvashi Butalia, interviewed by Sanya Chandra, Maanya Saran, Biplob K Das, and Yamini Krishnan 6. An ethos of fearlessness 52 Nisha Susan, interviewed by Meghna Anand 7. A lack of knowledge mars LGBTQ+ reporting 57 Bindumadhav Khire, interviewed by Pranati Narayan Visweswaran 8. Journalists need more subject expertise 62 Jagadeesh Narayana Reddy, interviewed by Spurthi Venkatesh 9. -

World Cultural Review 100

Vol-1; Issue-4 January - February 2020 Delhi RNI No.: DELENG/2019/78107 WORLD CULTURAL REVIEW www.worldcultureforum.org.in 100 OVER A ABOUT US World Culture Forum is an international Cultural Organization who initiates peacebuilding and engages in extensive research on contemporary cultural trends across the globe. We firmly believe that peace can be attained through dialogue, discussion and even just listening. In this spirit, we honor individuals and groups who are engaged in peacebuilding process, striving to establish a boundless global filmmaking network, we invite everyone to learn about and appreciate authentic local cultures and value cultural diversity in film. Keeping in line with our mission, we create festivals and conferences along with extensively researched papers to cheer creative thought and innovation in the field of culture as our belief lies in the idea – “Culture Binds Humanity. and any step towards it is a step towards a secure future. VISION We envisage the creation of a world which rests on the fundamentals of connected and harmonious co-existence which creates a platform for connecting culture and perseverance to build solidarity by inter-cultural interactions. MISSION We are committed to providing a free, fair and equal platform to all cultures so as to build a relationship of mutual trust, respect, and cooperation which can achieve harmony and understand different cultures by inter-cultural interactions and effective communications. RNI. No.: DELENG/2019/78107 World Cultural Review CONTENTS Vol-1; Issue-4, January-February 2020 100 Editor Prahlad Narayan Singh [email protected] Executive Editor Ankush Bharadwaj [email protected] Managing Editor Shiva Kumar [email protected] Associate Ankit Roy [email protected] Legal Adviser Dr. -

Two Films: Devi and Subarnarekha and Two Masters of Cinema / Partha Chatterjee

Two Films: Devi and Subarnarekha and Two Masters of Cinema / Partha Chatterjee Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak were two masters from the Bengali cinema of the 1950s. They were temperamentally dissimilar and yet they shared a common cultural inheritance left behind by Rabindranath Tagore. An inheritance that was a judicious mix of tradition and modernity. Ray’s cinema, like his personality, was outwardly sophisticated but with deep roots in his own culture, particularly that of the reformist Brahmo Samaj founded by Raja Ram Mohan Roy to challenge the bigotry of the upper caste Hindu Society in Bengal in the early and mid-nineteenth century. Ghatak’s rugged, home- spun exterior hid an innate sophistication that found a synthesis in the deep-rooted Vaishnav culture of Bengal and the teachings of western philosophers like Hegel, Engels and Marx. Satyajit Ray’s Debi (1960) was made with the intention of examining the disintegration of a late 19th century Bengali Zamidar family whose patriarch (played powerfully by Chabi Biswas) very foolishly believes that his student son’s teenaged wife (Sharmila Tagore) is blessed by the Mother Goddess (Durga and Kali) so as able to cure people suffering from various ailments. The son (Soumitra Chatterjee) is a good-hearted, ineffectual son of a rich father. He is in and out of his ancestral house because he is a student in Calcutta, a city that symbolizes a modern, scientific (read British) approach to life. The daughter-in-law named Doyamoyee, ironically in retrospect, for she is victimized by her vain, ignorant father-in-law, as it to justify the generous, giving quality suggested by her name. -

Barrenness and Bengali Cinema

1 “May You Be the Mother of A Hundred Sons!”: Barrenness vs. Motherhood in Bengali Cinema” Somdatta Mandal Department of English & Other Modern European Languages Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Borrowing from the recently published novel The Palace of Illusions, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s reimagining of the world-famous epic Mahabharata, let me begin with a well-known story. “Gandhari’s marriage, although she’d given up so much for its sake, was – like Kunti’s – not a happy one. Dhritarashtra was a bitter man. He never got over the fact that he’d been passed over by the elders – just because he was blind – when they decided which of the brothers should be king… The goal of Dhritarashtra’s life was to have a son who could inherit the throne after him. But here a problem arose, for in spite of his assiduous attempts Gandhari didn’t conceive for many years. When she finally did, it was too late. Kunti was already pregnant with Judhisthir. A year came. A year went. Yudhisthir was born. As the first male child of the next generation, the elders declared, the throne would be his. Dhritarashtra’s spies brought more bad news. Kunti was pregnant again. Now there were two obstacles between Dhritarashtra and his desire. Gandhari’s stomach grew large as a giant beehive, but her body refused to go into labor. Perhaps the frustrated king berated her, or perhaps the fact that he’d taken one of her waiting women as his mistress drove Gandhari to her act of desperation. She struck her stomach again and again until she bled, and bleeding gave birth to a huge, unformed ball of flesh. -

(1): Special Issue 100 Years of Indian Cinema the Changing World Of

1 MediaWatch Volume 4 (1): Special Issue 100 Years of Indian Cinema The Changing World of Satyajit Ray: Reflections on Anthropology and History MICHELANGELO PAGANOPOULOS University of London, UK Abstract The visionary Satyajit Ray (1921-1992) is India’s most famous director. His visual style fused the aesthetics of European realism with evocative symbolic realism, which was based on classic Indian iconography, the aesthetic and narrative principles of rasa, the energies of shakti and shakta, the principles of dharma, and the practice of darsha dena/ darsha lena, all of which he incorporated in a self-reflective way as the means of observing and recording the human condition in a rapidly changing world. This unique amalgam of self-expression expanded over four decades that cover three periods of Bengali history, offering a fictional ethnography of a nation in transition from agricultural, feudal societies to a capitalist economy. His films show the emotional impact of the social, economic, and political changes, on the personal lives of his characters. They expand from the Indian declaration of Independence (1947) and the period of industrialization and secularization of the 1950s and 1960s, to the rise of nationalism and Marxism in the 1970s, followed by the rapid transformation of India in the 1980s. Ray’s films reflect upon the changes in the conscious collective of the society and the time they were produced, while offering a historical record of this transformation of his imagined India, the ‘India’ that I got to know while watching his films; an ‘India’ that I can relate to. The paper highlights an affinity between Ray’s method of film-making with ethnography and amateur anthropology. -

Dossier De Presse Ghatak

Dossier de presse RÉTROSPECTIVE RITWIK GHATAK du 1er au 15 juin 2011 En partenariat média avec Un des grands artistes de l’histoire du cinéma indien. Son œuvre, trop courte, soumet le mélodrame, la chronique sociale ou la fresque historique à un traitement singulier. La Rivière Subarnarekha de Ritwik Ghatak (Inde/1962-65) - DR FILM + TABLE RONDE « Ritwik Ghatak, un cinéaste du Bengale » Samedi 4 juin à 14h30 À la suite de la projection, à 14h30, de Raison, discussions et un conte (1974, 121’) rencontre avec Sandra Alvarez de Toledo, France Bhattacharya, Raymond Bellour, Nikola Chesnais et Charles Tesson . Rencontre animée par Christophe Jouanlanne. Billet unique : Film + Table Ronde / Tarif plein 6.5€ - Tarif réduit 5€ - Forfait Atout prix et Cinétudiant 4€ /Libre pass : accès libre ACTUALITÉ EN LIBRAIRIE : Ritwik Ghatak. Des films du Bengale de Sandra Alvarez de Toledo (dir.) Éditions L’Arachnéen, 416 pages, 430 images. 39€. Cette rétrospective coïncide avec la sortie d’un livre, Ritwik Ghatak. Des films du Bengale , le premier en France et le seul de cette importance à lui être consacré. (Voir page 10) CONTACT PRESSE CINEMATHEQUE FRANCAISE Elodie Dufour Tél. : 01 71 19 33 65 / 06 86 83 65 00 / [email protected] FORCE DE GHATAK Par Raymond Bellour Ritwik Ghatak est l’un des grands artistes de l’histoire du cinéma indien. Son œuvre, trop courte (8 longs métrages), soumet le mélodrame, la chronique sociale ou la fresque historique à un traitement singulier, traversé par des éclats de poésie. Comment décrire les films de Ritwik Ghatak, l’un des plus méconnus parmi les très grands cinéastes ? Disons, si comparaison vaut raison : Ghatak, ce serait Sirk (qu’il ignore, comme presque tout le cinéma américain, si ce n’est Ford qu’il nomme une fois « un artiste considérable ») et Eisenstein (son cinéaste de chevet). -

Peepli [Live]: a Social Satire on Contemporary India

Peepli [Live]: A Social Satire on Contemporary India by Archana Nayak DEPARTMENT OF LIBERAL ARTS INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY HYDERABAD APRIL, 2015 Peepli [Live]: A Social Satire on Contemporary India A Thesis submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY by Archana Nayak DEPARTMENT OF LIBERAL ARTS INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY HYDERABAD APRIL, 2015 Dedicated to my father, Pramod Kumar Nayak and my friends DECLARATION I declare that this thesis represents my own ideas and words and where others ideas or words have been included; I have adequately cited and referenced the original sources. I also declare that I have adhered to all principles of academic honesty and integrity and have not misrepresented, plagiarized, fabricated or falsified any idea/data/fact/source in my submission. I understand that any violation of the above will result in disciplinary action by the Institute and can also evoke penal action from the sources that have not been properly cited or from whom proper permission has not been taken when needed. Signature of candidate ARCHANA NAYAK --------------------------------------------- Name of candidate LA13M1001 --------------------------------------------- Roll number CERTIFICATE It is certified that the work contained in the thesis entitled “Peepli [Live]: A Social Satire on Contemporary India” submitted by Archana Nayak (Roll No. LA13M1001) in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Philosophy to the Department of Liberal Arts, Indian Institute of Technology Hyderabad, is a record of bonafide research work carried out by her under my supervision and guidance. The results embodied in the thesis have not been submitted to any other University or Institute for the award of any degree or diploma. -

MLI-203 (Practice)

VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY MLISC. Examinations 2020 Semester II Subject: Master of Library and Information Science Paper: MLI-203 (Practice) Full Marks: 40 Time: 2HRS. Candidates are required to give their answers in their own words as far as practicable. Answer any one question from following questions: Prepare Main Entry, including Tracing of all Added Entries, References, as required for a Dictionary Catalogue following AACR2R. Prepare Subject Headings using any vocabulary control tool. (Mention the title and edition of the tool used). Mention the cataloguing condition above the Main Entry. Explain the rules used in preparing Main Entry heading and other areas of the Entry. And Prepare MARC 21 Bibliographic Format of the same item. 1. From Map Face: INDIAN TOURISM NATIONAL ATLAS OF INDIA Prepared under the direction of A. K. Kundu, Director, National Atlas and Thematic Mapping Organization, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, Kolkata Scale: 1:6,000,000 The boundary of Meghalaya shown in the map is interpreted from the North-Eastern Areas (re-organisation) Act 1971. Copyright: 1998 Based on Survey of India Maps, Central Government, State Government and other agencies Other Information: A coloured map Inner border size: 57.9x46.5 cm 2. From Map Face: THE WORLD Scale: 1:42,500,000(Approx) Copyright: INDIAN BOOK HOUSE, 1998 DREAMLAND PUBLICATIONS New Delhi ISBN 978-81-8451-121-5 The topographical details within India based upon Survey of India map The external boundaries and coastlines agree with the master copy certified by Survey of India. The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of 12 nautical miles measured from the base line International Boundary, country capital, other towns, river, major airports, sea routes are shown in the map Other Information: This coloured map printed on a sheet of paper. -

Ec 04 01 1967.Pdf

E.C. No. 485 ESTIMATES COMMITTEE (1967-68) FIRST REPORT (FOURTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF INFORMATION A.'ID BROA.DCA.~~Nq FJLM n~"STIWTf: 9F INDI~, POPN1\. PARLIAMENT LIBRARY (Lihrlt y &, H· f r I."" il.. rvice) C.-[llr"i G· ,vt.t:!'ublio.tioDL ) .2. Ace No R... ..• '{,.....7Cft! ; ... rs-, : •••• - 9~· ,........ ~'" ;;............ .J • ."", L -- L OK ..SABHA SECRETARIAl NEW DELHI Jyaistha, 1889 (Sale,,) Price : Rs~ 1.40 toM OP AU1"HORIS80 AGBNTS POR Ttm SALB OP LOIC SABRA SECRETARIAT PUBLICATIONS 51. Name of Agent Agency SL Name of Agent Na. No. No. ~cy ---- ,"":J ANDHRA PRADESH II. Chades Lambert &: CQIII- pany, 101, Mahatma I. Andhra Unlvenlty Gene- Gandhi Road,Opposite ra1 Cooperati ve Store. Qoclc Tower, Fort, Ltd., Waltair(Viaakha· Bombay 30 plIllIam) 8 12. The Current Book House, 2. G. R. Labhmipathy Che- Maruti Lane, Raghu- tty and 50111. General nath Dada;i Street, Merchants and Ne_ BombaY-I 60 Agenta, Newpet, Chan- drag;ri, ChlttoOt Dia· 13· Deccsan Book Stall, Fer- triet 94 guson College Road, Poona-4 .. 6, ASSAM ,. Wcatera Book Depot. Pan RAJASTHAN Bazar, Gauhati 7 '4· Information Centre, Go- BIHAR ..ernment oCR_lathan, Tripolia, J aipur City . 4· Amar Kitab Ghar, fost BOll: 78,Diagonal Road, UTTAR PRADESH Jamsbedpur 37 Swastik Induatrial WOtb, GUJARAT I,. 59, Holi Street, Meerut City a ,. Vilar Storea, Station Road, Anand 3' 16. Law Book Company, 6. The New Order Book Sardar Patel Marg, Company, Ellis Bridge. Allahabad-I 4B Ahmedabad-6 63 MADHYA PRADESH \VEST BENGAL 7. Madera Book HOWIe. 17. Granthaloka, 5/1. Am- Shiv Vila Palace. In- bica MookherjeeRoad, doreCity • 13 BeJgharia.