HEA Niger 2007 Report Final Based on N S Central Zones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USAID/DCHA Niger Food Insecurity Fact Sheet #1

BUREAU FOR DEMOCRACY, CONFLICT, AND HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE (DCHA) OFFICE OF U.S. FOREIGN DISASTER ASSISTANCE (OFDA) Niger – Food Insecurity Fact Sheet #1, Fiscal Year (FY) 2010 March 16, 2010 BACKGROUND AND KEY DEVELOPMENTS Since September 2009, residents of agro-pastoral and pastoral zones throughout Niger have experienced increasing food insecurity as a result of failed harvests—caused by short seasonal rains—and a second consecutive year of poor pasture conditions for livestock due to prolonged drought. The late start, early conclusion, and frequent interruption of the seasonal rains also resulted in the failure of cash crops. According to the USAID-funded Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), the September harvests failed completely in 20 to 30 percent of agricultural villages in the pastoral and agro-pastoral zones of Diffa Region and Tanout, Mirriah, and Gouré departments, Zinder Region. Other affected regions include Maradi, Tahoua, and Tillabéri, according to Government of Niger (GoN) and relief agency assessments. In December 2009, the GoN conducted an assessment of food stocks in nearly 10,000 households. The assessment did not review household ability to purchase cereals. Based on the assessment findings, the GoN reported in January 2010 that the 2.7 million residents of Niger’s pastoral and agro-pastoral zones faced severe food insecurity—defined as having less than 10 days’ worth of food in the household—and requested international assistance. On March 10, GoN Prime Minister Mahamadou Danda, head of the transitional government that took office on February 23, appealed for $123 million in international assistance to respond to food security needs. -

Farming Systems and Food Security in Africa

Farming Systems and Food Security in Africa Knowledge of Africa’s complex farming systems, set in their socio-economic and environmental context, is an essential ingredient to developing effective strategies for improving food and nutrition security. This book systematically and comprehensively describes the characteristics, trends, drivers of change and strategic priorities for each of Africa’s fifteen farming systems and their main subsystems. It shows how a farming systems perspective can be used to identify pathways to household food security and pov- erty reduction, and how strategic interventions may need to differ from one farming system to another. In the analysis, emphasis is placed on understanding farming systems drivers of change, trends and stra- tegic priorities for science and policy. Illustrated with full-colour maps and photographs throughout, the volume provides a comprehen- sive and insightful analysis of Africa’s farming systems and pathways for the future to improve food and nutrition security. The book is an essential follow-up to the seminal work Farming Systems and Poverty by Dixon and colleagues for the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations and the World Bank, published in 2001. John Dixon is Principal Adviser Research & Program Manager, Cropping Systems and Economics, Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), Canberra, Australia. Dennis Garrity is Senior Fellow at the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), based in Nairobi, Kenya, UNCCD Drylands Ambassador, and Chair of the EverGreen Agriculture Partnership. Jean-Marc Boffa is Director of Terra Sana Projects and Associate Fellow of the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), Nairobi, Kenya. Timothy Olalekan Williams is Regional Director for Africa at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), based in Accra, Ghana. -

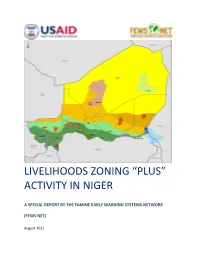

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

Niger a Country Profile

REF 910,3 ? 54c'L/5" E92 NIGER ,Niger A Country Profile Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance Agency for International Development Washlngton, D.C. 20523 Niger LIS Y A ALGERIA International boundary Ddpartement bourdary * National capital Tamanrasset 0 DLpartement capital - Railroad Road 0 50 100 150 Kilometers a 50 100 1 Miles eBilma 1 -.. (( M ALI '\lm 9 5 5Ta)oua ae5 1 11 Go ur e' . :5 - . arni . Mha.... iarr7: BENINi~ / ( "-'er,IL" LChad ; ak-i-Tt rs UPPER ' Base 504113 11-79 (544513) NIGER: A COUNTRY PROFILE prepared for The Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance Agency for International Development Department of State Washington, D.C. 20523 by Mary M. Rubino Evaluation Technologies, Inc. c",C1 Arlington, Virginia under contract AID/SOD/PDC-C-3345 The country profile of Niger Is part of a series designed to provide baseline country data in support of the planning and relief operations of the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA). Content, scope, and sources have evolved over the course of the last several years and the relatively narrow focus is intentional. We hope that the information provided will also be useful to others in the disaster assistance and development communities. Every effort is made to obtain current, reliable data; unfortunately it Is not possible to issue updates as fast as changes would warrant. We invite your comments and corrections. Address these and other queries to OFDA, A.I.D., as given above. April 1985 OFDA COUNTRY PROFILES: APRIL 1985 AFRICA CARIBBEAN Burkina Faso CARICOM Regional Profile Cape Verde Antigua Chad Barbados East Africa Regional Profile Belize Djibouti Dominica Ethiopia Grenada Kenya Guyana Somalia Montserrat Sudan St. -

Pdf | 709.71 Kb

NIGER Monthly Food Security Update December 2006 Alert level: No alert Watch Warning Emergency SUMMARY Summary of food security and nutrition Summary of food security and nutrition..................................…..1 Household food security was adequate in December, following good harvests of rainfed Current hazards summary .....…..1 crops. Regular market supplies of miscellaneous foodstuffs, steadily falling prices for staple grain crops, and access to multiple sources of income from sales of crops such as Agropastoral situation ...........…..2 cowpeas, chufa nuts and sesame are helping to improve household food access. Conditions on agropastoral markets However, there are localized production deficits in certain parts of the country, including ...............................................…..3 southwestern Tillabery, northern Zinder and northern Tahoua. The January FEWS NET Food security, health and nutrition Food Security Update will present a clearer picture of the situation and the numbers of ...............................................…..4 residents affected once the data from the joint SAP-INS-WFP-FEWS NET-FAO Relief measures.....................…..4 household vulnerability survey has been processed. As far as the situation in farming areas is concerned, with the good conditions created by the 2006 rainy season, farming activities for off-season crops are being stepped up. This year’s assistance program by the government and its food security partners is focusing on supplying seeds for vegetable and potato crops and cuttings for tuber crops and on site development work in truck farming areas. The Ministry of Animal Resources has just published its findings on pastoral conditions. Niger has an overall forage surplus of 4,905,028 MT of dry matter, including all types of forage production, meeting 100 percent of its livestock needs, subject to a balanced distribution of watering holes and the containment of brush fires. -

Niger Monthly Food Security Update, December 2006

NIGER Monthly Food Security Update December 2006 Alert level: No alert Watch Warning Emergency SUMMARY Summary of food security and nutrition Summary of food security and nutrition..................................…..1 Household food security was adequate in December, following good harvests of rainfed Current hazards summary .....…..1 crops. Regular market supplies of miscellaneous foodstuffs, steadily falling prices for staple grain crops, and access to multiple sources of income from sales of crops such as Agropastoral situation ...........…..2 cowpeas, chufa nuts and sesame are helping to improve household food access. Conditions on agropastoral markets However, there are localized production deficits in certain parts of the country, including ...............................................…..3 southwestern Tillabery, northern Zinder and northern Tahoua. The January FEWS NET Food security, health and nutrition Food Security Update will present a clearer picture of the situation and the numbers of ...............................................…..4 residents affected once the data from the joint SAP-INS-WFP-FEWS NET-FAO Relief measures.....................…..4 household vulnerability survey has been processed. As far as the situation in farming areas is concerned, with the good conditions created by the 2006 rainy season, farming activities for off-season crops are being stepped up. This year’s assistance program by the government and its food security partners is focusing on supplying seeds for vegetable and potato crops and cuttings for tuber crops and on site development work in truck farming areas. The Ministry of Animal Resources has just published its findings on pastoral conditions. Niger has an overall forage surplus of 4,905,028 MT of dry matter, including all types of forage production, meeting 100 percent of its livestock needs, subject to a balanced distribution of watering holes and the containment of brush fires. -

Situation Report

BUREAU FOR DEMOCRACY, CONFLICT, AND HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE (DCHA) OFFICE OF U.S. FOREIGN DISASTER ASSISTANCE (OFDA) Niger – Malnutrition and Food Insecurity Fact Sheet #2, Fiscal Year (FY) 2010 June 10, 2010 Note: The last fact sheet was dated March 16, 2010. KEY DEVELOPMENTS On May 20, the Government of Niger (GoN), U.N. agencies, and the USAID-funded Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) released the findings of a household food security survey carried out in April. The survey found that more than 3.3 million people—or more than 22 percent of Niger’s population of approximately 15.5 million people—are currently experiencing severe food insecurity. In addition, the survey found that more than 3.8 million people, or more than 25 percent of the population, are currently experiencing moderate food insecurity. In total, more than 7.1 million people—or nearly 48 percent of Niger’s population—are presently classified as either severely or moderately food-insecure. From April 27 to May 11, 2010, staff from USAID/OFDA and USAID’s Office of Food for Peace (USAID/FFP) traveled to field locations in Niger, met with relief agencies and GoN officials, and visited project sites to assess rising acute malnutrition rates and household food insecurity. The team concluded that the crisis is becoming increasingly critical as the hunger season enters its most severe phase. According to FEWS NET, the current hunger season, which in many affected areas started in January rather than the typical April or May, will likely last until July for pastoralists and until September for households that rely on agriculture. -

La Décentralisation Au Niger: Le Cas De La Mobilisation Des Ressources Financières Dans La Ville De Niamey

Université de Montréal La décentralisation au Niger : le cas de la mobilisation des ressources financières dans la ville de Niamey par Colette Nyirakamana Département de science politique Faculté des arts et des sciences Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures en vue de l’obtention du grade de Maîtrise es sciences en Science politique Février 2015 © Colette Nyirakamana, 2015 Université de Montréal Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales Ce mémoire intitulé La décentralisation au Niger : le cas de la mobilisation des ressources financières dans la ville de Niamey présenté par : Colette Nyirakamana A été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes : Pascale Dufour Présidente du jury Mamoudou Gazibo Membre du jury Christine Rothmayr Allison Directrice de recherche Résumé La décentralisation implantée en 2004 au Niger, a pour objectif de promouvoir le développement « par le bas » et de diffuser les principes démocratiques dans les milieux locaux, afin d’améliorer les conditions de vie des populations. Les recherches sur le sujet font état d’un écart considérable entre les objectifs et les réalisations de la décentralisation. Les facteurs avancés pour expliquer cet écart sont entre autres, le faible appui technique et financier de l’État envers les collectivités territoriales ou encore la quasi-inexistence d’une fonction publique locale qualifiée et apte à prendre en charge les projets de décentralisation. Toutefois, ces observations s’avèrent insuffisantes pour rendre compte des difficultés rencontrées par les acteurs de la décentralisation au Niger. Nous affirmons que les partis politiques jouent un rôle fondamental dans le processus de décentralisations. Ceux-ci diffusent des stratégies d’influence politique et de patronage dans les arènes locales. -

Republique Du Niger Troisieme Rapport National Du Niger

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER CABINET DU PREMIER MINISTRE CONSEIL NATIONAL DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT POUR UN DEVELOPPEMENT DURABLE SECRETARIAT EXECUTIF ============= TROISIEME RAPPORT NATIONAL DU NIGER DANS LE CADRE DE LA MISE EN ŒUVRE DE LA CONVENTION INTERNATIONALE DE LUTTE CONTRE LA DESERTIFICATION (CCD) DOCUMENT FINAL Décembre 2004 1 SOMMAIRE PREAMBULE ........................................................................................................................................................3 SIGLES ET ABRÉVIATIONS .............................................................................................................................4 I. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................................6 II. RESUME ...........................................................................................................................................................6 2.1 LE CENTRE DE LIAISON....................................................................................................................................6 2.2. ÉTAT D’AVANCEMENT DU PROGRAMME D’ACTION NATIONAL (PAN) : ........................................................7 2.3. PARTICIPATION A UN PROGRAMME D’ACTION SOUS- REGIONAL OU REGIONAL...............................................8 2.4. ORGANE NATIONAL DE COORDINATION (ONC).............................................................................................9 2.5. NOMBRE TOTAL D’ONG ACCREDITEES ..........................................................................................................9 -

Niger - Région De Maradi Date De Production : 1 Février 2019

Pour Usage Humanitaire Uniquement CARTE DE REFERENCE Niger - Région de Maradi Date de production : 1 février 2019 " " 6°0'0"E " " 8°0'0"E " " " " " " " " Azanane " " " " Azemosse " " Matara Jataw Kanak Sofoua " !( " Jiji " " Idiguini " Abalak Ingall " " " " Assades " " " " Kao " " " " " " " " " Koutou Anou Rhissa Kada Tamaya "" " " " " Aderbissinat " Bammi " " " " " Gayse " " " " " Agada Ibnou " " " " Ibingar Garage " " " " " " Zongon Hamada " " " "" " Zongo Jibbi " " Abouhaya " Boundou Doubore Abarmou Gali " Oro Bammo " " " " Amat " " Amat Doutchi Maoude " " Chikakatene/Azaguelal " " " " " " Akaddane " " " Garou Bourou " Abouhaya Souka Oro Koulloua " Akoubounou " Zongo Alher " " " Yacouba Tahirou " !( Eguef N'Adarass " Tabalak " " " Tchimbalho Zongo Abdourahamane " " " Lougaere Kouloua Ouroga " " " " Tenhya Abalak " Wirguiss " Tiguitout " " " Boundou Tankari " " Tiridat Bakki " " " " Boundou Kinaro " " " " " " " Zongo Hicham " " " " Tamiguitt " " " Rouga Koine " " Boundou Barade " Abanga"r Tankosan " " " " Janjore " " Tagaza " " Rouga Mai Bouje " " " "Rijia Danneri " Boka Jaho """ " " " " " " Magayda Boundou Guae Boundou Dalli " Rouga Bermini " " " Tchounkoultou " Chighamanene " Aminata I Gorah Baba Ahmed Teffougante " " Rouga Sourame Guaho " " " " " Rouga Dodjo " "" " " Zongon Issoufou Boundou Adouna " " " Pourel " " Akoubounou " " " " Tayki Aminata Ii " " Zongon Sadjo Rouga Ibrahim Riskoua Rouga Oubankadi Maoude " Intalak " " " " " " " " " Boundou Dangui Boundou Kinone " " Rouga Ounfana " " " " Rouga Bago Girka " " " " " " Tourouf -

Food Insecurity

BUREAU FOR DEMOCRACY, CONFLICT, AND HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE (DCHA) OFFICE OF U.S. FOREIGN DISASTER ASSISTANCE (OFDA) Niger – Food Insecurity Fact Sheet #1, Fiscal Year (FY) 2010 March 16, 2010 BACKGROUND AND KEY DEVELOPMENTS Since September 2009, residents of agro-pastoral and pastoral zones throughout Niger have experienced increasing food insecurity as a result of failed harvests—caused by short seasonal rains—and a second consecutive year of poor pasture conditions for livestock due to prolonged drought. The late start, early conclusion, and frequent interruption of the seasonal rains also resulted in the failure of cash crops. According to the USAID-funded Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), the September harvests failed completely in 20 to 30 percent of agricultural villages in the pastoral and agro-pastoral zones of Diffa Region and Tanout, Mirriah, and Gouré departments, Zinder Region. Other affected regions include Maradi, Tahoua, and Tillabéri, according to Government of Niger (GoN) and relief agency assessments. In December 2009, the GoN conducted an assessment of food stocks in nearly 10,000 households. The assessment did not review household ability to purchase cereals. Based on the assessment findings, the GoN reported in January 2010 that the 2.7 million residents of Niger’s pastoral and agro-pastoral zones faced severe food insecurity—defined as having less than 10 days’ worth of food in the household—and requested international assistance. On March 10, GoN Prime Minister Mahamadou Danda, head of the transitional government that took office on February 23, appealed for $123 million in international assistance to respond to food security needs. -

Farming Systems and Food Security in Africa

Farming Systems and Food Security in Africa Knowledge of Africa’s complex farming systems, set in their socio-economic and environmental context, is an essential ingredient to developing effective strategies for improving food and nutrition security. This book systematically and comprehensively describes the characteristics, trends, drivers of change and strategic priorities for each of Africa’s fifteen farming systems and their main subsystems. It shows how a farming systems perspective can be used to identify pathways to household food security and pov- erty reduction, and how strategic interventions may need to differ from one farming system to another. In the analysis, emphasis is placed on understanding farming systems drivers of change, trends and stra- tegic priorities for science and policy. Illustrated with full-colour maps and photographs throughout, the volume provides a comprehen- sive and insightful analysis of Africa’s farming systems and pathways for the future to improve food and nutrition security. The book is an essential follow-up to the seminal work Farming Systems and Poverty by Dixon and colleagues for the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations and the World Bank, published in 2001. John Dixon is Principal Adviser Research & Program Manager, Cropping Systems and Economics, Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), Canberra, Australia. Dennis Garrity is Senior Fellow at the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), based in Nairobi, Kenya, UNCCD Drylands Ambassador, and Chair of the EverGreen Agriculture Partnership. Jean-Marc Boffa is Director of Terra Sana Projects and Associate Fellow of the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), Nairobi, Kenya. Timothy Olalekan Williams is Regional Director for Africa at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), based in Accra, Ghana.