Youth Orchestra Participation and Perceived Benefit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Sistema Around the World

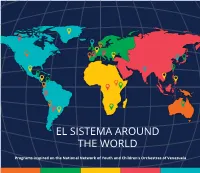

EL SISTEMA AROUND THE WORLD Programs inspired on the National Network of Youth and Children’s Orchestras of Venezuela A MODEL OF PEACE AND PROGRESS FOR THE WORLD The National Network of Youth and choirs are social and personal life Children’s Orchestras and Choirs of schools, where children can culti- Venezuela, commonly known as El vate positive abilities and attitudes, Sistema, is a state-funded social and and ethic, aesthetic and spiritual cultural program created in 1975 values. All members acquire qual- by the Venezuelan maestro José ities like self-concept, self-esteem, Antonio Abreu. The Simon Bolivar self-confidence, discipline, patience, Music Foundation is the governing and commitment. They learn to be body of El Sistema and is attached to perseverant and to perform a healthy the Ministry of People’s Power for the professional competition, and lead- President’s Office and Government ership; working constantly to achieve Management Follow-Up of the their goals and excellence, while Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, coexisting in a tolerant and friendly aimed at teaching children from environment, which stimulates them an early age to become upright towards a peace culture. members of the society. The international reputation of El Through individual and collective Sistema’s ensembles and musicians music practice, el Sistema has taken them to appear at the most incorporates children from all levels prestigious venues in the world, as of social stratification: 66% come from peace ambassadors, and has earned low income homes or live in adverse them many awards such as the 2008 conditions and vulnerable areas, while Prince of Asturias Award for the Arts the remaining 34% come from urban and the UNESCO International Music areas with better access possibilities, Award. -

Nuveen Investments Emerging Artist Violinist Julia Fischer Joins the Cso and Riccardo Muti for June Subscription Concerts at Symphony Center

For Immediate Release: Press Contacts: June 13, 2016 Eileen Chambers, 312-294-3092 Photos Available By Request [email protected] NUVEEN INVESTMENTS EMERGING ARTIST VIOLINIST JULIA FISCHER JOINS THE CSO AND RICCARDO MUTI FOR JUNE SUBSCRIPTION CONCERTS AT SYMPHONY CENTER June 16 – 21, 2016 CHICAGO—Internationally acclaimed violinist Julia Fischer returns to Symphony Center for subscription concerts with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) led by Music Director Riccardo Muti on Thursday, June 16, at 8 p.m., Friday, June 17, at 1:30 p.m., Saturday, June 18, at 8 p.m., and Tuesday, June 21, at 7:30 p.m. The program features Brahms’ Serenade No. 1 and Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major with Fischer as soloist. Fischer’s CSO appearances in June are endowed in part by the Nuveen Investments Emerging Artist Fund, which is committed to nurturing the next generation of great classical music artists. Julia Fischer joins Muti and the CSO for Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. Widely recognized as the first “Romantic” concerto, Beethoven’s lush and virtuosic writing in the work opened the traditional form to new possibilities for the composers who would follow him. The second half of the program features Brahms’ Serenade No. 1. Originally composed as chamber music, Brahms later adapted the work for full orchestra, offering a preview of the rich compositional style that would emerge in his four symphonies. The six-movement serenade is filled with lyrical wind and string passages, as well as exuberant writing in the allegro and scherzo movements. German violinist Julia Fischer won the Yehudi Menuhin International Violin Competition at just 11, launching her career as a solo and orchestral violinist. -

Honors Concerts 2015

Honors Concerts 2015 Presented By The St. Louis Suburban Music Educators Association and Education Plus St. Louis Suburban Music Educators Association Affiliated With Education Plus Missouri Music Educators Association MENC - The National Association for Music Education www.slsmea.com EXECUTIVE BOARD – 2014-16 President 6th Grade Orchestra VP Jason Harris, Maplewood-Richmond Heights Twinda, Murry, Ladue President-Elect MS Vocal VP Aaron Lehde, Ladue Lora Pemberton, Rockwood Valerie Waterman, Rockwood Secretary/Treasurer James Waechter, Ladue HS Jazz VP Denny McFarland, Pattonville HS Band VP Vance Brakefield, Mehlville MS Jazz VP Michael Steep, Parkway HS Orchestra VP Michael Blackwood, Rockwood Elementary Vocal Katy Frasher, Orchard Farm HS Vocal VP Tim Arnold, Hazelwood MS Large Ensemble/Solo Ensemble Festival Director MS Band VP David Meador, St. Louis Adam Hall, Pattonville MS Orchestra VP Tiffany Morris-Simon, Hazelwood Order a recording of today’s concert in the lobby of the auditorium or Online at www.shhhaudioproductions.com St. Louis Suburban 7th and 8th Grade Treble Honor Choir Emily Edgington Andrews, Conductor John Gross, Accompanist January 10, 2015 Rockwood Summit High School 3:00 P.M. PROGRAM Metsa Telegramm …………………………………………………. Uno Naissoo She Sings ………………………………………………………….. Amy Bernon O, Colored Earth ………………………………………………….. Steve Heitzig Dream Keeper ………………………………………………….. Andrea Ramsey Stand Together …………………………………………………….. Jim Papoulis A BOUT T HE C ONDUCTOR An advocate for quality musical arts in the community, Emily Edgington Andrews is extremely active in Columbia, working with children and adults at every level of their musical development. She is the Fine Arts Department Chair and vocal music teacher at Columbia Independent School, a college preparatory campus. Passionate about exposing students to quality choral music education, she has received recognition for her work in the classroom over the years, most recently having been awarded the Charles J. -

Music Director & ESYO Symphony

Position: Music Director & ESYO Symphony Orchestra Conductor Type of Position: Full time salaried with benefits; reports to the Board of Directors SUMMARY: Empire State Youth Orchestra’s Music Director engages youth in the joyful pursuit of musical excellence. The Music Director (MD) works in close collaboration with the Board and Executive Director and serves as the lead artistic liaison with community groups and educational institutions. The MD provides artistic leadership for the organization, and oversees the educational and artistic development of all ESYO students through rehearsals, performances, and collaboration with artistic staff. The MD maintains a standard of excellence among the artistic staff through interaction, evaluation, example, curricula and artistic leadership. The MD collaborates with the CHIME Administrative Director to ensure alignment between the CHIME program and the overall artistic vision of ESYO, and additionally provides support to CHIME faculty with respect to the inclusion of CHIME students into audition-based performing ensembles. The MD is an ambassador to the greater community including professional musicians, public and private school music teachers, and potential students. The MD is a musician of the highest quality, possesses a commanding ability to communicate through music, and is committed to inspiring young people to pursue excellence through music. KEY RESPONSIBILITIES: Artistic Leader • Ensures a high level of musical excellence of all ensembles • Articulates the artistic vision of ESYO through the development of new and engaging programs • Collaborates with and supports conductors in realizing the scope and vision of ESYO • Collaborates with the CHIME Administrative Director to support the development and advancement of CHIME • Collaborates with the Education Coordinator to continuously assess the music education needs of all ESYO members. -

Richmond Symphony Announces a New Digital Music School - Richmond Symphony School of Music - a Community Music School

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE - ANNOUNCEMENT Wednesday, July 29, 2020 Richmond Symphony announces a new digital music school - Richmond Symphony School of Music - a community music school Spurred in part by challenges and disruptions of service resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, the Richmond Symphony is working to continue its music education programs by shifting them to a digital format, housed under the new Richmond Symphony School of Music (RSSoM). The Richmond Symphony School of Music (RSSoM) will launch as a virtual music school open to the public in October, its summer pilot is underway. This community music school will provide a broad range of programming to Central Virginia, the Commonwealth, and beyond, and will establish the foundation upon which a brick-and-mortar community music school will be established in the heart of Richmond. RSSoM will serve all who love music from birth to adulthood: Pre-K students, K-12 students, and adults. As a virtual music school, we will utilize video conferencing software and an array of both digital and traditional resources to supplement instruction and exploration, and to facilitate real-time lessons and classes. Registration begins August 31 and classes start the week of October 5. A diverse and dedicated team of musicians, students, teachers, parents, administrators, and music education professionals representing our region’s leaders in the field have been hard at work researching and practicing with these technologies and developing the school throughout the spring and summer of 2020. Our sincere hope and dream is that RSSoM will grow to take its place among Richmond’s many fine institutions as the hub of a universal spectrum of activities, where music education is accessible to all and where all styles and traditions of music are valued, respected, and pursued with dedication, passion, and love. -

The Pelly Concert Orchestra Committee

Mystical Magic… and Tales from the East – 6th July 2019 From the Chair... Good evening and welcome to the final concert of the season. I am sure we are all here for the very same reason To enjoy the music, and have a good time So I thought I would carry on with a rhyme! Our previous Chair wrote a rhyme at Christmas 2015 So I thought I would follow with our Mystical Magical theme From Harry Potter to The King and I Followed on with Aladdin and Madame Butterfly. There’s The Potter Waltz and The Steppes of Central Asia All mixed in with Lawrence of Arabia An eclectic mix, I am sure you’ll agree Enjoy the break with a nice cup of tea! My spell as Chair has now come to an end To the orchestra my best wishes I send As a playing member I’ve enjoyed it all And I leave now with this rallying call: Keep coming to concerts to hear music live Next season we will be doing concerts, five With a special family concert in December Which really will be one to remember It’s The Snowman film with live music from us An afternoon concert without any fuss The kids will love it, I’m sure you’ll agree Salesian College 15th December is where it’ll be. Karen Carter Chair Page 1 Mystical Magic… and Tales from the East – 6th July 2019 TONIGHT'S PROGRAMME 1. Entrance of the Sirdar Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov Arr. Richard L. Weaver 2. Theme from Lawrence of Arabia Maurice Jarre Arr. -

Musx Brochure 2012-14

The MusXchange programme has been funded with support from the MusXchange 2012–14 European Commission. This publication reflects the view only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use FINAL REPORT which may be made of the information contained therein. MusXchange 2012–14 A Cooperation Project of the European Federation of National Youth Orchestras EFNYO’s programme for fostering transnational mobility of pre-professional musicians pre-professional opening horizons Youth mobility matters Orchestras innovative training concerts new skills needs europe changing new mindsets With its 35 member organisations, the European Federation of National Youth Orchestras (EFNYO) is an association deeply rooted in European musical life. It provides a platform for the exchange of expertise in music training and performance between the leading national youth orchestras of Europe and takes over responsibility for skilling future generations of musicians. In this regard, the Federation truly benefits from its unique po- sition at the interface of higher music education and the music profession. Following its beginnings in 1996, the musicians’ exchange programme of EFNYO has developed into an indispensable instrument for the profes- sionalization of the music sector in the European Union. It gives young pre-professional musicians opportunities to gain orchestral practice in partner orchestras abroad, discover new repertoire, different performance styles and orchestra traditions, meet conductors, teachers, and young artists in a different cultural environment. This experience will widen their perception of musicians’ job profiles today, help them to compete on the European labour market, and increase their social, intercultural and language skills. The programme “MusXchange” has certainly been the highlight among EFNYO cooperation projects since its foundation in 1994. -

EPIC Project Application Successful

Weberstr. 59A | 53113 BONN | DE www.EuropeanChoralAssociation.org +49 228 9125663 [email protected] EPIC Project Application Successful The European Choral Association – Europa Cantat is delighted to announce the success of its application for the project EPIC (Emerging Professionals: Internationalisation of music Careers)! Collective music‐making is a powerful tool to bring people and nations together. Many auditioned youth choirs and orchestras are active in Europe both on national and transnational level, bringing together ambitious young musicians who are looking for new challenges and chances. The national ensembles help emerging musicians to boost their careers at the national level by providing them with invaluable skills and professional experience that complement their formal training. Entering the international market, however, requires specific intercultural work methods, social skills, management skills, ability to work in an international context, business skills, understanding of the employment market, and more. What is EPIC? How will EPIC work? The vision of the EPIC project is to: The project aims will be reached through the following activities running from November 2019 to the end of 2021: • improve the training of • A data collection, mapping the career path of former members of emerging professionals auditioned youth ensembles (orchestras and choirs) • foster the creation of new • An involvement of the EuroChoir and the World Youth Choir as ensembles across Europe transnational laboratories for providing -

European Union Youth Orchestra Summer Tour 2015

European Union Youth Orchestra Summer Tour 2015 Principal Corporate Partner At United Technologies, we believe that ideas and inspiration create opportunities without limits. UTC applauds the European Union Youth Orchestra for its important role in transcending cultural, social, economic, religious, and political boundaries in the pursuit of musical excellence. To learn more, visit utc.com. Welcome The months and weeks of build up to a major six week concert tour are a complex yet exhilarating experience. The sheer volume of tasks – from international travel plans for hundreds of young musicians Contents from over 30 countries to providing for the needs of a global audience of thousands – appear as a series of almost impenetrable Orchestra Board 2 hurdles. Until the dust begins to settle, and the prospect of great EU messages 4 music played by some of today’s most polished young performers under the leadership of inspirational conductors becomes The EUYO 6 increasingly present on the horizon. Tribute to Joy Bryer 8 As we all know, Europe faces some particularly tough times at the Landmark moments 9 moment. All the more reason then to trumpet the unifying diversity Summer tour programme 10 at the heart of the EUYO, in an orchestra that shows us a tangible route for how we should live as Europeans, with young musicians Conductors 14 from 28 EU countries working together, harmoniously, yet with Soloists 16 limitless energy, aspiration and excellence. The Orchestra 18 As the CEO of an orchestra such as this I can only help create success by mirroring the shared leadership at the heart of the EUYO and Leverhulme Summer School 25 its performances. -

Social Inclusion

the ensemble 12 | 2014 A NEWSLETTER FOR THE U.S. & CANADIAN EL SISTEMA MOVEMENT Social Inclusion FROM THE EDITOR By Keane Southard, Composer Intern, In this issue we highlight El Sistema’s manifold Bennington College vitality in Brazil and consider two different ways that As a Fulbright scholar, I spent last year in Brazil studying programs interpret and exemplify the goal of “social several of the El Sistema-inspired programs there. I inclusion.” wanted to understand the Sistema movement in Brazil Here is a third way to think about social inclusion – and to find out what other programs, particularly in in terms of organizations rather than people, joining the United States, my home country, might learn from forces with other music education projects to serve their experiences. One of the most pertinent issues Ricardo Castro with NEOJIBA musicians. an entire community. Issues of inclusion and exclu- I discovered was that El Sistema’s principle of “social Photo: Keane Southard sion can make the difference between success and inclusion” can be approached in different ways. around the city, toured Europe, and gained a reputation failure for organizations as well as for individuals. for excellence, did the program begin to open núcleos Some programs aim to achieve social inclusion by For a model of ambitious organizational inclusion, in poor communities around Bahia. Thus demand was focusing on populations that have traditionally we need look no further than Venezuela’s neighbor generated from the ground up; many communities now been excluded from classical music education. The Colombia, where the Sistema program, Batuta (“ba- want their own youth orchestras, and children practice Orchestrando a Vida (Orchestrating Life) program has ton”), has from its inception coexisted with a num- hard in order to audition for the top orchestra someday. -

POSITION VACANCY Responsibilities: Serve As Conductor for Cadenza

POSITION VACANCY Youth Orchestra Conductor The Saint Charles County Youth Orchestra is seeking an interim conductor for the Cadenza Orchestra group of the Saint Charles County Youth Orchestra for the remainder of the 2019-2020 season. This is a part time conducting position for an intermediate orchestra group. The position would begin in January 4, 2020 and continue until the summer concert on May 9, 2020. Responsibilities: ● Serve as Conductor for Cadenza level of Saint Charles County Youth Orchestra ● Lead all orchestra rehearsals on Saturday mornings from 9am-10:30am ● Participate in SCCYO annual auditions as adjudicator and help determine orchestra placement and seating ● Audition prospective players throughout the season for placement and seating ● Determine repertoire for Cadenza musical performances (3 per year) ● Must have a conducting background ● Possess strong teaching skills especially with middle and high school grade students Administration: ● Select repertoire for Cadenza from the SCCYO music library and new selections within the SCCYO music budget ● Coordinate with the Executive Director regarding absences, performances, and auditions ● Communicate with SCCYO Cadenza members regarding rehearsal notes and concert related information Special Skills: ● Communicate effectively with SCCYO Executive Director, Board Members, students, and parents ● Maintain current knowledge of regional schools and community music schools with band and orchestra programs ● Willing to adhere to SCCYO mission and vision ● Be committed to the overall musical growth of students in the Cadenza group Education/Experience: ● Minimum Bachelor’s degree in Music Performance, Conducting, or Music Education, with at least two years’ experience leading an orchestra . -

Orchestrating Venezuela's Youth

Introduction Todos lo comentan, nadie lo delata. (Everyone talks, no one tells.) —Héctor Lavoe, “Juanito Alimaña” n August 2007 an audience of thousands crammed into London’s Royal IAlbert Hall for the electrifying Proms debut by Gustavo Dudamel and the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra of Venezuela (SBYO). “Was this the greatest Prom of all time?” asked the Daily Telegraph’s arts editor (Gent 2007). A turning point in the orchestra’s rise to global prominence, this concert’s im- pact stretched back to Venezuela, where President Hugo Chávez read out the rapturous U.K. press reports on his television show Aló Presidente and announced an expansion of the music education program known as El Sistema, of which the SBYO forms the summit. As I left the Albert Hall, exhilarated, I decided to study this phenomenon. * * * Three years later, I was sitting in a car outside Montalbán, El Sistema’s model music school in Caracas. With its high walls topped with barbed wire and gates manned by security, it had the air of a correctional facility. The director came out to the car to greet me and show me in. As I walked through the main en- trance, I saw a large poster—of me. They had downloaded my photo and biog- raphy from the Internet and created a poster to announce my visit. I barely had time to register this before a brass fanfare sounded off to my left. An ensemble of a dozen French horns launched into “Hymn to Joy,” announcing my entrance with perfect precision. I listened, entranced.