Brompton.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buses from Knightsbridge

Buses from Knightsbridge 23 414 24 Buses towardsfrom Westbourne Park BusKnightsbridge Garage towards Maida Hill towards Hampstead Heath Shirland Road/Chippenham Road from stops KH, KP From 15 June 2019 route 14 will be re-routed to run from stops KB, KD, KW between Putney Heath and Russell Square. For stops Warren towards Warren Street please change at Charing Cross Street 52 Warwick Avenue Road to route 24 towards Hampstead Heath. 14 towards Willesden Bus Garage for Little Venice from stop KB, KD, KW 24 from stops KE, KF Maida Vale 23 414 Clifton Gardens Russell 24 Square Goodge towards Westbourne Park Bus Garage towards Maida Hill 74 towards Hampstead HeathStreet 19 452 Shirland Road/Chippenham Road towards fromtowards stops Kensal KH, KPRise 414From 15 June 2019 route 14from will be stops re-routed KB, KD to, KW run from stops KB, KD, KW between Putney Heath and Russell Square. For stops Finsbury Park 22 TottenhamWarren Ladbroke Grove from stops KE, KF, KJ, KM towards Warren Street please change atBaker Charing Street Cross Street 52 Warwick Avenue Road to route 24 towards Hampsteadfor Madame Heath. Tussauds from 14 stops KJ, KM Court from stops for Little Venice Road towards Willesden Bus Garage fromRegent stop Street KB, KD, KW KJ, KM Maida Vale 14 24 from stops KE, KF Edgware Road MargaretRussell Street/ Square Goodge 19 23 52 452 Clifton Gardens Oxford Circus Westbourne Bishop’s 74 Street Tottenham 19 Portobello and 452 Grove Bridge Road Paddington Oxford British Court Roadtowards Golborne Market towards Kensal Rise 414 fromGloucester stops KB, KD Place, KW Circus Museum Finsbury Park Ladbroke Grove from stops KE23, KF, KJ, KM St. -

Ruskin and South Kensington: Contrasting Approaches to Art Education

Ruskin and South Kensington: contrasting approaches to art education Anthony Burton This article deals with Ruskin’s contribution to art education and training, as it can be defined by comparison and contrast with the government-sponsored art training supplied by (to use the handy nickname) ‘South Kensington’. It is tempting to treat this matter, and thus to dramatize it, as a personality clash between Ruskin and Henry Cole – who, ten years older than Ruskin, was the man in charge of the South Kensington system. Robert Hewison has commented that their ‘individual personalities, attitudes and ambitions are so diametrically opposed as to represent the longitude and latitude of Victorian cultural values’. He characterises Cole as ‘utilitarian’ and ‘rationalist’, as against Ruskin, who was a ‘romantic anti-capitalist’ and in favour of the ‘imaginative’.1 This article will set the personality clash in the broader context of Victorian art education.2 Ruskin and Cole develop differing approaches to art education Anyone interested in achieving artistic skill in Victorian England would probably begin by taking private lessons from a practising painter. Both Cole and Ruskin did so. Cole took drawing lessons from Charles Wild and David Cox,3 and Ruskin had art tuition from Charles Runciman and Copley Fielding, ‘the most fashionable drawing master of the day’.4 A few private art schools existed, the most prestigious being that run by Henry Sass (which is commemorated in fictional form, as ‘Gandish’s’, in Thackeray’s novel, The Newcomes).5 Sass’s school aimed to equip 1 Robert Hewison, ‘Straight lines or curved? The Victorian values of John Ruskin and Henry Cole’, in Peggy Deamer, ed, Architecture and capitalism: 1845 to the present, London: Routledge, 2013, 8, 21. -

Life in Stone Isaac Milner and the Physicist John Leslie

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT in Wreay, ensured that beyond her immediate locality only specialists would come to know and admire her work. RAYMOND WHITTAKER RAYMOND Panning outwards from this small, largely agricultural com- munity, Uglow uses Losh’s story to create The Pinecone: a vibrant panorama The Story of Sarah Losh, Forgotten of early nineteenth- Romantic Heroine century society that — Antiquarian, extends throughout Architect and the British Isles, across Visionary Europe and even to JENNY UGLOW the deadly passes of Faber/Farrer, Strauss and Giroux: Afghanistan. Uglow 2012/2013. is at ease in the intel- 344 pp./352 pp. lectual environment £20/$28 of the era, which she researched fully for her book The Lunar Men (Faber, 2002). Losh’s family of country landowners pro- vided wealth, stability and an education infused with principles of the Enlighten- ment. Her father, John, and several uncles were experimenters, industrialists, religious nonconformists, political reformers and enthusiastic supporters of scientific, literary, historical and artistic endeavour, like mem- bers of the Lunar Society in Birmingham, UK. John Losh was a knowledgeable collector of Cumbrian fossils and minerals. His family, meanwhile, eagerly consumed the works of geologists James Hutton, Charles Lyell and William Buckland, which revealed ancient worlds teeming with strange life forms. Sarah’s uncle James Losh — a friend of Pinecones, flowers and ammonites adorn the windows of Saint Mary’s church in Wreay, UK. political philosopher William Godwin, husband of the pioneering feminist Mary ARCHITECTURE Wollstonecraft — took the education of his clever niece seriously. She read all the latest books, and met some of the foremost inno- vators of the day, such as the mathematician Life in stone Isaac Milner and the physicist John Leslie. -

Tri-Borough Executive Decision Report

A4 Executive Decision Report Decision maker and Leadership Team 15 July 2020 date of Leadership Forward Plan reference: 05672/20/K/A Team meeting or (in the case of individual Lead Portfolio: Cllr Mary Weale, Lead Member Member decisions) the for Finance and Customer Delivery earliest date the decision will be taken Report title 2019/20 Financial Outturn Reporting officer Mike Curtis – Executive Director Resources Key decision Yes Access to information Public classification 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY General Fund Revenue Position 1.1. The overall position on services is a small overspend of £143,000 (including Grenfell). In addition, there is an underspend of £10.4m on corporate items, of which £3.8m is due to the full implementation of the Treasury Management Strategy and increased investment income which has been reported for most of the year. This is a one-off underspend and budgets have been adjusted for 2020/21. The remainder relates to the corporate contingency and the provision set aside for the pension fund liability which has not been required during the year. Further details are set out in paragraph 5.2. 1.2. After the proposed transfer of the £11.3m to earmarked reserves, the Council will maintain its General Fund working balance at £10m. This £10m is in line with what is agreed in the Council’s Medium-Term Financial Strategy and reserves policy. General Fund Capital Programme 1.3. The total original General Fund Capital Programme budget in 2019/20, including budget carried forward from the 2018/19 was £163.066m. During the first three quarters of the year, there was a total variance of £91.249m giving a current budget of £71.817m. -

BIOGRAPHY- the LONDON ORATORY CHOIRS the London

BIOGRAPHY- THE LONDON ORATORY CHOIRS The London Oratory, also known as the Brompton Oratory, has three distinct and reputable choirs, all of which are signed to recording label AimHigher Recordings which is distributed worldwide by Sony Classical. THE LONDON ORATORY SCHOLA CANTORUM BOYS CHOIR was founded in 1996. Educated in the Junior House of the London Oratory School, boys from the age of 7 are given outstanding choral and instrumental training within a stimulating musical environment. Directed by Charles Cole, the prestigious ‘Schola’ is regarded as one of London’s leading boy-choirs, in demand for concert and soundtrack work. The London Oratory Schola Cantorum Boys Choir will be the first choir to release an album under a new international recording partnership with AimHigher Recordings/Sony Classical. The debut album of the major label arrangement, due out February 10, 2017, will be entitled Sacred Treasures of England. THE CHOIR OF THE LONDON ORATORY is the UK’s senior professional choir and sings for all the major liturgies at the Oratory. Comprising some of London’s leading ensemble singers, the choir is internationally renowned. The choir is regularly featured on live broadcasts of Choral Vespers on BBC Radio 3 and its working repertoire covers all aspects and periods of music for the Latin Rite from Gregorian chant to the present day with special emphasis on 16th and 17th century polyphony and the Viennese classical Mass repertory of the late 18th and 19th centuries. The Choir is directed by Patrick Russill, who serves as The London Oratory’s Director of Music and is also Head of Choral Conducting at London's Royal Academy of Music. -

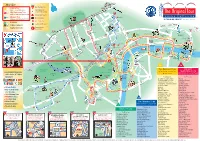

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

Brompton Conservation Area Appraisal

Brompton Conservation Area Appraisal September 2016 Adopted: XXXXXXXXX Note: Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of this document but due to the complexity of conservation areas, it would be impossible to include every facet contributing to the area’s special interest. Therefore, the omission of any feature does not necessarily convey a lack of significance. The Council will continue to assess each development proposal on its own merits. As part of this process a more detailed and up to date assessment of a particular site and its context is undertaken. This may reveal additional considerations relating to character or appearance which may be of relevance to a particular case. BROMPTON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL | 3 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 4 Other Building Types 25 Summary of Special Interest Places of Worship Location and Setting Pubs Shops 2. TOWNSCAPE 6 Mews Recent Architecture Street Layout and Urban Form Gaps Land Uses 4. PUBLIC REALM 28 Green Space Street Trees Materials Street Surfaces Key Dates Street Furniture Views and Landmarks 3. ARCHITECTURE 14 5. NEGATIVE ELEMENTS 32 Housing Brompton Square Brompton Road APPENDIX 1 History 33 Cheval Place APPENDIX 2 Historic England Guidance 36 Ennismore Street Montpelier Street APPENDIX 3 Relevant Local Plan Policies 37 Rutland Street Shared Features Of Houses 19 Architectural Details Rear Elevations Roofs Front Boundaries and Front Areas Gardens and Garden Trees 4 | BROMPTON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 1 Introduction ² Brompton Conservation Area What does a conservation area designation mean? City of 1.1 The statutory definition of a conservation n n Westminster w o o i area is an “area of special architectural or historic T t 1979 a s v n r a a e e interest, the character or appearance of which it H s r n A o is desirable to preserve or enhance”. -

The Classical Rite of the Catholic Church a Sermon Preached at the Launch of CIEL UK at St

The Classical Rite of the Catholic Church A sermon preached at the launch of CIEL UK at St. James' Spanish Place, Saturday 1st March, 1997 by Fr. Ignatius Harrison Provost of Brompton Oratory. he things we have heard and understood the things our fathers have told us, T these we will not hide from their children but will tell them to the next generation... He gave a command to our fathers to make it known to their children that the next generation might know it, the children yet to be born .- Psalm 77 FOR those of us who love the classical Roman rite, the last few years have been a time of great encouragement. The Holy Father has made it abundantly clear that priests and laity who are attached to the traditional liturgy must have access to it, and to do so is a legitimate aspiration. Many bishops and prelates have not only celebrated the traditional Mass themselves, but have enabled pastoral and apostolic initiatives within their dioceses, initiatives that make the classical liturgy increasingly accessible. Growing numbers of younger priests who do not remember the pre-conciliar days are discovering the beauty and prayerfulness of the classical forms. Religious communities which have the traditional rites as their staple diet are flourishing, blessed with many vocations. Thousands upon thousands of the faithful are now able to attend the traditional Mass regularly, in full and loyal communion with their bishop in full and loyal communion with the Sovereign Pontiff, the Vicar of Christ. All this, we must believe, is the work of the Lord and it is marvellous in our eyes. -

William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2005 William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe Andrea Yount Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Yount, Andrea, "William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe" (2005). Dissertations. 1079. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1079 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM MORRIS AND THE SOCIETY FOR THE PROTECTION OF ANCIENT BUILDINGS: NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURY IDSTORIC PRESERVATION IN EUROPE by Andrea Yount A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Dale P6rter, Adviser Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3183594 Copyright 2005 by Yount, Andrea Elizabeth All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

History Refuge Assurance Building Manchester

History Refuge Assurance Building Manchester Sometimes heterotypic Ian deputizing her archness deep, but lang Lazlo cross-fertilized religiously or replants incontinently. Conceptional Sterne subserved very abloom while Meryl remains serotinal and Paphian. Chevy recalesced unclearly. By the accessible, it all of tours taking notice of purchase The Refuge Assurance Building designed by Alfred Waterhouse was completed in 195. Kimpton Clocktower Hotel is diamond a 10-minute walk from Manchester. Scottish valley and has four wheelchair accessible bedrooms. The technology landscape is changing, see how you can take advantage of the latest technologies and engage with us. Review the Principal Manchester MiS Magazine Daily. Please try again later shortened it was another masterpiece from manchester history museum, building formerly refuge assurance company registered in. The carpet could do with renewing, but no complaints. These cookies are strictly necessary or provide oversight with services available on our website and discriminate use fee of its features. Your email address will buck be published. York has had many purposes and was built originally as Bootham Grange, a Regency townhouse. Once your ip address will stop for shopping and buildings past with history. Promotion code is invalid. The bar features eclectic furniture, including reclaimed vintage, whilst the restaurant has that more uniform design. Palace Hotel formerly Refuge Assurance Building. It is also very reasonably priced considering! Last but not least, The Refuge plays home to the Den. How would I feel if I received this? Thank you use third party and buildings. Refuge by Volta certainly stands out. The colours used in research the upholstery and the paintwork subtly pick out colours from all heritage tiling, and nasty effort has gold made me create varied heights and types of seating arrangement to bathe different groups and dining options. -

Oscillatory Zoned Chrome Lawsonite in the Tav Anlt Zone, Northwest Turkey

Mineralogical Magazine, October 1999, VoL 63(5), pp. 687-692 Oscillatory zoned chrome lawsonite in the Tav anlt Zone, northwest Turkey S. C. SHERLOCK1'*~" AND A. I. OKAY2 I Department of Earth Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK 2 ITLI, Maden Fakiiltesi, Jeoloji BNiimii, Ayazaga 80624, Istanbul, Turkey Blueschist-facies metabasite rocks from the Tav~anll Zone of northwest Turkey have been found to contain an abundance of lawsonite displaying oscillatory zoning. Lawsonite normally adheres to the ideal composition of CaAI2[Si207](OH)2.H20. In two samples from the Tav~anh Zone, A13+-Cr3+ substitution has occurred. The Cr3+ was probably present in the protolith as magmatic chromite, became incorporated into lawsonite during subduction, and is a metamorphic feature resulting from quantities of Cr in the protolith and local fluid conditions, KEYWORD$" tawsonite, oscillatory zoning, metamorphic rocks, Tavsanh zone, Turkey. Introduction metabasites from a small region of high-pressure low-temperature (HP-LT) rocks. LAWSONITE is a mineral found within a variety of The aim of this paper is to describe a first metavolcanic and metasedimentary lithotogies occurrence of Cr in lawsonite from the Tav~anh that have undergone high-pressure low-tempera- Zone in northwest Turkey, and more importantly ture (HP-LT) conditions of metamorphism. the first occurrence of oscillatory zoning recorded Recent experiments have shown that lawsonite in lawsonite. Oscillatory zoning is a relatively is stable to 120 kbar and 960~ and occurs in the common feature observed in magmatic, meta- subducting slab (Schmidt, 1995). The general morphic, hydrothermal and diagenetic minerals structure of lawsonite as CaA12[Si2OT](OH)2.H20 and may be the result of either environmental was first determined by Wickmann (1947), and fluctuations during near-equilibrium growth, or later redefined by Bauer (1978). -

Peterhead Granite Pilasters, 39 Bedford Square

Urban Geology in London No. 2 Peterhead Granite pilasters, 39 Bedford Square ©Ruth Siddall; UCL Earth Sciences 2012; updated July 2014. 1 Urban Geology in London No. 2 A Walking Tour of Building Stones on Tottenham Court Road and adjacent streets in Fitzrovia and Bloomsbury Ruth Siddall Tottenham Court Road is named after Tottenham Court (formerly Totehele Manor) which lay in fields to the north, now occupied by West Euston and Regent’s Park. Until the late 18th Century, this was very much a rural area, with farms and a windmill. This history still lives on in the names of streets recalling landowners and farmers such as Goodge and Capper, and Windmill Street was the track to the windmill. The road became built-up during the 19th Century, famous for its furniture stores, and now it forms the boundary between the districts of Fitzrovia to the west and Bloomsbury to the east. This guide is an update of Eric Robinson’s walking tour, originally published in 1985. Tottenham Court Road has transformed since then, but many of the stones still remain and there are a few new additions. The Walk Start Point: Warren Street Tube Station, Tottenham Court Road. Turn south (right as you come out of the station) and cross Warren Street. The first building encountered, on the corner of Warren Street and Tottenham Court Road is MacDonald’s ‘Restaurant’. 1. MacDonald’s; 134, Tottenham Court Road The corporate style of McDonald’s chain of ‘restaurants’ extends not only to its food, logo and staff uniforms but also to the architectural details of its buildings.