“A Powerful Underclaim”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SBF Overview

SECTION 02 Global Implementation of Mizu To Ikiru SBF Overview We are developing our five regional businesses by focusing on the needs of customers in each country and market. Number of employees Business overview Main products (as of December 31, 2018) Main company name (start year) Suntory Foods Limited (1972) We are strengthening the position of long-selling brands like Suntory Beverage Solution Limited (2016) Suntory Holdings Suntory Tennensui and BOSS, while offering a wide portfolio Suntory Beverage Service Limited (2013) that includes tea, juice drinks, and carbonated beverages. We JAPAN 9,682 Japan Beverage Holdings Inc. (2015) also develop integrated beverage services such as vending Suntory Foods Okinawa Limited (1997) machines, cup vending machines, and water dispensers. Suntory Products Limited (2009) Our business in Europe focuses on brands that have been Suntory Beverage & Food (SBF)* locally loved for many years. Alongside core brands like Orangina Schweppes Holding B.V. (2009) Orangina in France, and Lucozade and Ribena in the UK, EUROPE 3,798 Lucozade Ribena Suntory Limited (2014) we are also developing Schweppes carbonated beverages and a wide range of other products. Our business in Asia consists of soft drinks and health supplements. We have established joint venture companies Suntory Beverage & Food Asia Pte. Ltd. (2011) that manage the soft drink businesses in Vietnam, Thailand, BRAND’S SUNTORY INTERNATIONAL Co., Ltd. (2011) ASIA and Indonesia in a way that fits the specific needs of each 6,963 PT SUNTORY GARUDA BEVERAGE (2011) market. The health supplement business focuses on the Suntory PepsiCo Vietnam Beverage Co., Ltd. (2013) manufacture and sale of the nutritional drink, BRAND’S Suntory PepsiCo Beverage (Thailand) Co., Ltd. -

Comparison of Sports Drink Products 2017

Nutritional Comparison of Sports Drink Products; 2017 All values are per 100mL. All information obtained from nutritional panels on product and from company websites. Energy (kj) CHO (g) Sugar (g) Sodium Potassium (mg/mmol) (mg/mmol) Sports Drink Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Blackcurrant 104 5.8 5.8 28.0 (1.2mmol) 33 (0.9mmol) Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Berry Ice 104 5.8 5.8 28.0 (1.2mmol) 33 (0.9mmol) Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Mountain Blast 105 5.8 5.8 28.0 (1.2mmol) 33 (0.9mmol) Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Lemon Lime 103 5.8 5.8 28.0 (1.2mmol) 33 (0.9mmol) Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Gold Rush 103 5.8 5.8 28.0 (1.2mmol) 33 (0.9mmol) Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Silver Charge 107 5.8 5.8 28.0 (1.2mmol) 33 (0.9mmol) Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Pineapple Storm (+ coconut water) 97 5.5 5.5 38.0 (1.7mmol) 46 (1.2mmol) Powerade Zero Sports Drink Berry Ice 6.1 0.1 0.0 51.0 (2.2mmol) - Powerade Zero Sports Drink Mountain Blast 6.8 0.1 0.0 51.0 (2.2mmol) - Powerade Zero Sports Drink Lemon Lime 6.8 0.1 0.0 56.0 (2.2mmol) - Maximus Sports Drink Red Isotonic Sports Drink 133 7.5 6.0 31.0 - Maximus Sports Drink Big O Isotonic Sports Drink 133 7.5 6.0 31.0 - Maximus Sports Drink Green Isotonic Sports Drink 133 7.5 6.0 31.0 - Maximus Sports Drink Big Squash Isotonic Sports Drink 133 7.5 6.0 31.0 - Gatorade Sports Drink Orange Ice 103 6.0 6.0 51.0 (2.3mmol) 22.5 (0.6mmol) Gatorade Sports Drink Tropical 103 6.0 6.0 51.0 (2.3mmol) 22.5 (0.6mmol) Gatorade Sports Drink Berry Chill 103 6.0 6.0 51.0 -

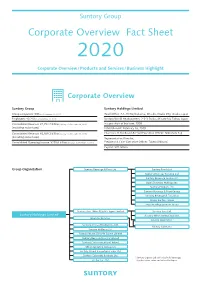

Corporate Overview Fact Sheet 2020

Suntory Group Corporate Overview Fact Sheet 2020 Corporate Overview/ Products and Services / Business Highlight Corporate Overview Suntory Group Suntory Holdings Limited Group companies: 300 (as of December 31, 2019) Head Office: 2-1-40 Dojimahama, Kita-ku, Osaka City, Osaka, Japan Employees: 40,210 (as of December 31, 2019) Suntory World Headquarters: 2-3-3 Daiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan Consolidated Revenue: ¥2,294.7 billion (January 1 to December 31, 2019) Inauguration of business: 1899 (excluding excise taxes) Establishment: February 16, 2009 Consolidated Revenue: ¥2,569.2 billion (January 1 to December 31, 2019) Chairman of the Board & Chief Executive Officer: Nobutada Saji (including excise taxes) Representative Director, Consolidated Operating Income: ¥259.6 billion (January 1 to December 31, 2019) President & Chief Executive Officer: Takeshi Niinami Capital: ¥70 billion Group Organization Suntory Beverage & Food Ltd. Suntory Foods Ltd. Suntory Beverage Solution Ltd. Suntory Beverage Service Ltd. Japan Beverage Holdings Inc. Suntory Products Ltd. Suntory Beverage & Food Europe Suntory Beverage & Food Asia Frucor Suntory Group Pepsi Bottling Ventures Group Suntory Beer, Wine & Spirits Japan Limited Suntory Beer Ltd. Suntory Holdings Limited Suntory Wine International Ltd. Beam Suntory Inc. Suntory Liquors Ltd.* Suntory (China) Holding Co., Ltd. Suntory Spirits Ltd. Suntory Wellness Ltd. Suntory MONOZUKURI Expert Limited Suntory Business Systems Limited Suntory Communications Limited Other operating companies Suntory Global Innovation Center Ltd. Suntory Corporate Business Ltd. * Suntory Liquors Ltd. sells alcoholic beverage Sunlive Co., Ltd. (spirits, beers, wine and others) in Japan. Suntory Group Corporate Overview Fact Sheet Products and Services Non-alcoholic Beverage and Food Business/Alcoholic Beverage Business Non-alcoholic Beverage and Food Business We deliver a wide range of products including mineral water, coffee, tea, carbonated drinks, sports drinks and health foods. -

Energy Drinks and Children

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Energy drinks and children Thirteenth Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 27 November 2018 HC 821 Published on 4 December 2018 by authority of the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee The Science and Technology Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Government Office for Science and associated public bodies. Current membership Norman Lamb MP (Liberal Democrat, North Norfolk) (Chair) Vicky Ford MP (Conservative, Chelmsford) Bill Grant MP (Conservative, Ayr, Carrick and Cumnock) Darren Jones MP (Labour, Bristol North West) Liz Kendall MP (Labour, Leicester West) Stephen Metcalfe MP (Conservative, South Basildon and East Thurrock) Carol Monaghan MP (Scottish National Party, Glasgow North West) Damien Moore MP (Conservative, Southport) Neil O’Brien MP (Conservative, Harborough) Graham Stringer MP (Labour, Blackley and Broughton) Martin Whitfield MP (Labour, East Lothian) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/science and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the relevant inquiry page of the Committee’s website. Committee staff The current staff of the Committee are: Danielle Nash (Clerk), Zoë Grünewald (Second Clerk), Dr Harry Beeson (Committee Specialist), Dr Elizabeth Rough (Committee Specialist), Martin Smith (Committee Specialist), Sonia Draper (Senior Committee Assistant), Julie Storey (Committee Assistant), and Joe Williams (Media Officer). -

Knowledge of and Attitudes to Sports Drinks of Adolescents Living in South Wales, UK RM FAIRCHILD

Knowledge of and attitudes to sports drinks of adolescents living in South Wales, UK R M FAIRCHILD BSc (Hons), PhD1 D BROUGHTON BDS (Hons) 2 M Z MORGAN BSc (Hons), PGCE, MPH, MPhil, FFPH2 1Cardiff Metropolitan University, Department of Healthcare and Food, Cardiff CF5 2YB 2Applied Clinical Research and Public Health, College of Biomedical and Life Sciences, Cardiff University, School of Dentistry, Heath Park, Cardiff CF14 4XY Key words: oral health, children, sports drinks Word count including abstract 2,399 Abstract – 270 Corresponding author: Ruth M Fairchild (Dr) Cardiff School of Health Sciences Department of Healthcare and Food Cardiff Metropolitan University, Department of Healthcare and Food, Western Avenue Cardiff CF5 2YB ABSTRACT Background: The UK sports drinks market has a turnover in excess of £200M. Adolescents consume 15.6% of total energy as free sugars, much higher than the recommended 5%. Sugar sweetened beverages, including sports drinks, account for 30% of total free sugar intake for those aged 11-18 years. Objective: To investigate children’s knowledge and attitudes surrounding sports drinks. Method: 183 self-complete questionnaires were distributed to four schools in South Wales. Children aged 12 - 14 were recruited to take part. Questions focussed on knowledge of who sports drinks are aimed at; the role of sports drinks in physical activity and the possible detrimental effects to oral health. Recognition of brand logo and sports ambassadors and the relationship of knowledge to respondent’s consumption of sports drinks were assessed. Results: There was an 87% (160) response rate. 89.4% (143) claimed to drink sports drinks. 45.9% thought that sports drinks were aimed at everyone; approximately a third (50) viewed teenagers as the target group. -

Cornwall South West Drinks Brochure 2016 Contents

LWC LWC Cornwall Depot South West Depot (Jolly’s Drinks) King Charles Business Park Wilson Way Old Newton Road Pool Industrial Estate Heathfield Redruth | Cornwall Newton Abbot | Devon TR15 3JD TQ12 6UT 0845 345 1076 0844 811 7399 [email protected] [email protected] ER SE SUMM ASON CORNWALL SOUTH WEST DRINKS BROCHURE 2016 CONTENTS Local Brands ���������������������������������������2-18 National Brands ������������������������������ 19-42 LWC ARE THE LARGEST INDEPENDENT WHOLESALER IN THE UK We currently carry over 6000 product lines But are you competitively priced? including: 127 different draught products of The last three years has seen us grow our sales beers, lagers and ciders from £110 million to £180 million this year� 1,212 different spirit lines We have only done this because we offer the best 740 soft drink lines balance of service, product range and price anywhere 1,035 different wines in the UK today� We are totally committed to 131 cider lines helping our customers grow their sales and 97 RTD’s margins through competitive pricing and a wide Over 1,000 different cask ales and varied product range� Are LWC backed and supported by Sounds good how do I get in touch? all national suppliers? Simple, for Cornwall call Naomi Mankee on LWC are partner wholesaler status with Coors, 0845 345 1076 or email cornwall@lwc-drinks�co�uk InBev and Heineken UK� We also work in for South West call Lucy Tucker on conjunction with ALL regional brewers in the UK� 0844 811 7399 or email southwest@lwc-drinks�co�uk This means that -

“Obesity - from Clinical Practice to Research” Donal O’Shea October 12Th 2013 IPNA, Athlone

“Obesity - from clinical practice to research” Donal O’Shea October 12th 2013 IPNA, Athlone. Outline of talk • A bit of background • Why we are where we are • A healthy lifestyle • Some of our research Obesity: like no previous epidemic • Diabetes • Cancer • Dementia • Cardiovascular Disease • Asthma • Arthritis Causes 4000 – 6000 Deaths per year in Ireland (Pop 5 million) Suicide deaths 486 (2011), Road deaths 161 (2012) Percentage increase in BMI categories since 1986 Sturm and Hattori, Int J Obes 2012 Body Mass Index 40 & 50 BMI 40 BMI 52 Body Mass Index 40 & 50 BMI 40 BMI 52 Guess 32 Guess 41 General facts • Average woman (5 ft 4) normal weight up to 10 stone (65 kilos) needs 1700-1800 kcal per day up tp 50yo then 1500kcal per day • Average man (5ft 10) normal weight up to12 stone (78 kilos) needs 1900-2000 kcal per day up to 50yo then 1700 kcal General Facts • From age of 4 to 14 child should be half age in stone General Facts • From age of 4 to 14 child should be half age in stone (depends on height) 4 year old – 2 stone 8 year old – 4 stone 14 year old – 7 stone And then they fill out….. Childhood Obesity in Ireland (and Europe) • 25% 3 year olds overweight/obese • 25% 9 years olds overweight/obese • low self image, concept and self esteem Growing up in Ireland 2009 Median BMI for each 5-year rise in age of onset of overweight O’Connell et al JPHN 2011 Young Scientist 2012 Age v Weight 75 70 65 60 55 50 45 40 Weight(kg) 35 30 25 20 15 4 4.5 5 5.5 6 6.5 7 7.5 8 8.5 9 9.5 10 10.5 11 11.5 12 12.5 13 13.5 14 Age • Study cohort - 6328 -

Long Term Sponsored By

SILVER Long term Sponsored by Lucozade Ogilvy & Mather Lucozade Sport: Longitudinal Case Study COMPANY PROFILE Ogilvy Ireland, part of Ogilvy worldwide is owned by WPP, the world’s second largest marketing communications organisation. The Ogilvy worldwide network includes 497 offices in 125 countries with 14,000+ employees working in over 50 languages providing Advertising, Promotions, Direct Marketing, Public Relations and Digital marketing services. Ogilvy & Mather Dublin, is one of Ireland’s largest advertising agencies handling a diverse portfolio of local Irish clients ranging from finance through major consumer brands to social marketing. INTRODUCTION AND BacKGROUND Launched in Ireland long before ‘Brand Beckham’ and the cult of the sports celebrity, Lucozade Sport recognized the potential in the growing trend for serious amateur participation in sport in Ireland as well as the influence that professional sport was having on amateur players and coaches. “Ten years ago you’d see lads on the team bus on the way up to Croker having a fag. You’d just never see that now” Dessie Dolan, Westmeath senior footballer (FBI Research, summer 2008). Sport is about results. So is this case Lucozade Sport pioneered a drinks category now worth more than €52 million. Before its launch sports drinks were virtually unknown, so our 157 SILVER challenge was to tap in to the hydration and nutrition needs of athletes who were just beginning to understand more about the demands placed on their bodies by sports. Importantly we also needed to establish Lucozade Sport as an Irish brand strong enough to withstand the threat of international brands like Powerade or Gatorade. -

Suntory Holdings Limited

Suntory Holdings Limited August 5, 2016 SUMMARY OF CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE SIX MONTHS ENDED JUNE 30, 2016 (English Translation, UNAUDITED) Company Name: Suntory Holdings Limited (URL: http://www.suntory.com/) Representative: Takeshi Niinami, President Contact: Toru Niwa, Head of Public Relations Public Relations Office: Tel:+81(0)3 5579-1150 Tel:+81(0)6 6346-0835 (Fractions of millions have been truncated) 1. Consolidated operating results and financial positions for the six months of the current fiscal year (January 1, 2016 - June 30, 2016) (1) Operating results (% figures represent change from the same period of the previous fiscal year) Net income attributable Net sales Operating income Ordinary income to owners of parent Six months ended \million% ¥ million % \million % \million % June 30, 2016 1,273,069 3.0 87,277 14.0 75,647 14.2 35,633 129.5 June 30, 2015 1,236,336 11.5 76,527 18.8 66,238 6.0 15,529 (9.7) Referential Information : Income before amortization of goodwill and others Net income attributable Operating income Ordinary income to owners of parent Six months ended ¥ million % \million % \million % June 30, 2016 121,387 10.3 109,758 10.0 63,476 44.4 June 30, 2015 110,049 31.499,759 21.9 43,943 40.2 Note:Income before amortization of goodwill and others = Income + Amortization of Goodwill, Trademarks and other recognized in connection with M&A Diluted net income per Basic net income per share share Six months ended ¥ ¥ June 30, 2016 52.11 - June 30, 2015 22.73 - (2) Financial positions Ratio of equity Total -

2021 Citizen Science Brand Audit Report August 2021 Authors: Amy Slack (Surfers Against Sewage) Sally Menna Turner (Salthub) Executive Summary

2021 Citizen science Brand Audit Report August 2021 Authors: Amy Slack (Surfers Against Sewage) Sally Menna Turner (SaltHub) Executive summary Surfers Against Sewage (SAS) launched its flagship week of the Million Mile Clean from 11th May - 23rd May. As part of this event, volunteers took part in a national brand audit, an important citizen science programme to drive corporate behaviour change. 2021 citizen science As the UK’s biggest coordinated beach clean event, over 50,000 For the Dirty Dozen companies, 52% of items would be captured through volunteers took part in 600 cleans, covering 350,000 miles in total an ‘all-in’ Deposit Return Scheme (DRS) design. Over 80% of coca-cola’s brand audit over the Million Mile flagship week. Of these volunteers, 3,917 walked packaging, the top polluter, is estimated to be captured through this scheme. report and cleaned 11,139 miles of beaches, rivers, mountains and more, 63% of all items monitored as part of the brand audit were unbranded. submitting 377 brand audit data sets. A total of 26,983 items of Cigarette butts were by far the biggest contributor at 25% of the packaging pollution were monitored as part of the brand audit. 01 Executive summary unbranded items. Although receiving considerable attention over the The top 12 most polluting brands were responsible for 48% of all last 18 months, PPE only accounted for 2.5% of all pollution monitored 02 introduction packaging pollution monitored during the audit. There was little change through the audit. Whilst clearly an emerging threat, it is important that 03 Polluting brands in the most polluting brands of 2021 compared to 2019 results with this should not distract from the significant amount of pollution caused Coca-Cola, Walkers, McDonalds, Cadbury, Tesco, Lucozade, Costa by brands and their parent companies. -

How Safe Is Your Blast of Caffeine? Energy Drinks Are a £1Billion-A-Year Industry in the UK and Hugely Popular Among the Young

Printer Friendly Page 1 of 3 From The Times September 29, 2008 How safe is your blast of caffeine? Energy drinks are a £1billion-a-year industry in the UK and hugely popular among the young. But some experts caution that the caffeine content is a potential health risk and can bring on symptoms of a heart attack Pete Bee Energy drinks have become the elixir of a generation that considers itself in need of more of a jolt than can be obtained from a mere cup of coffee. Around 330 million litres of products such as Red Bull, the UK's bestseller, are consumed every year in Britain and the super-caffeinated drinks market is worth £1billion annually. As they flood our shelves, though, some experts are concerned that they are potentially so harmful that they should carry health warnings. With some containing seven times as much caffeine as a strong cup of black coffee and 14 times that in a can of cola, there is a risk of harmful addiction, it has been claimed. Professor Roland Griffiths, of The Johns Hopkins University, Maryland, said in a study last week that there was a danger of some people becoming physically dependent on energy drinks and experiencing side-effects ranging from panic attacks and nausea to chest pains and racing pulses. Drinks claiming to provide a jolt that will improve everything from work performance and concentration to reaction speed and stimulated metabolism are nothing new. As long ago as 1886 when the Atlanta-based pharmacist John Pemberton invented Coca-Cola - a product that originally allegedly contained a line of cocaine in each bottle and was marketed as “one of the most delightful, cheering and invigorating of fountain drinks” - consumers have swallowed the concept that they can sup their way to vitality. -

THE TRUTH ABOUT SPORTS DRINKS Sports Drinks Are Increasingly Regarded As an Essential Adjunct for Anyone Doing Exercise, but the Evidence for This View Is Lacking

Watch Panorama on BBC iPlayer THE TRUTH ABOUT SPORTS DRINKS Sports drinks are increasingly regarded as an essential adjunct for anyone doing exercise, but the evidence for this view is lacking. Deborah Cohen investigates the marketing of the science of hydration rehydrate; drink ahead of thirst; train with the New York marathon. Manufacturers According to Noakes, the sports drink industry your gut to tolerate more fluid; your of sports shoes and the drink and nutritional needed to inculcate the idea that fluid intake was brain doesn’t know you’re thirsty—the supplement industries spotted a growing market. as critical for athletic performance as proper train- public and athletes alike are bombarded One drink in particular was quick to capitalise ing. “It became common for athletes to state that with messages about what they should on the burgeoning market. Robert Cade, a renal the reason why they ran poorly during a race was Pdrink, and when, during exercise. But these drink- physician from the University of Florida, had pro- not because they had trained either too little or too ing dogmas are relatively new. In the 1970s, mar- duced a sports drink in the 1960s that contained much, but because they had become dehydrated. athon runners were discouraged from drinking water, sodium, sugar, and monopotassium phos- This was a measure of the success of the industry fluids for fear that it would slow them down, says phate with a dash of lemon.1 2 Gatorade—named in conditioning athletes to believe that what they Professor Tim Noakes, Discovery health chair of after the American Football team, the Gators, that drank during exercise was as important a deter- exercise and sports science at Cape Town Univer- it was developed to help—could prevent and cure minant of their performance as their training,” sity.