Energy Drinks and Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SBF Overview

SECTION 02 Global Implementation of Mizu To Ikiru SBF Overview We are developing our five regional businesses by focusing on the needs of customers in each country and market. Number of employees Business overview Main products (as of December 31, 2018) Main company name (start year) Suntory Foods Limited (1972) We are strengthening the position of long-selling brands like Suntory Beverage Solution Limited (2016) Suntory Holdings Suntory Tennensui and BOSS, while offering a wide portfolio Suntory Beverage Service Limited (2013) that includes tea, juice drinks, and carbonated beverages. We JAPAN 9,682 Japan Beverage Holdings Inc. (2015) also develop integrated beverage services such as vending Suntory Foods Okinawa Limited (1997) machines, cup vending machines, and water dispensers. Suntory Products Limited (2009) Our business in Europe focuses on brands that have been Suntory Beverage & Food (SBF)* locally loved for many years. Alongside core brands like Orangina Schweppes Holding B.V. (2009) Orangina in France, and Lucozade and Ribena in the UK, EUROPE 3,798 Lucozade Ribena Suntory Limited (2014) we are also developing Schweppes carbonated beverages and a wide range of other products. Our business in Asia consists of soft drinks and health supplements. We have established joint venture companies Suntory Beverage & Food Asia Pte. Ltd. (2011) that manage the soft drink businesses in Vietnam, Thailand, BRAND’S SUNTORY INTERNATIONAL Co., Ltd. (2011) ASIA and Indonesia in a way that fits the specific needs of each 6,963 PT SUNTORY GARUDA BEVERAGE (2011) market. The health supplement business focuses on the Suntory PepsiCo Vietnam Beverage Co., Ltd. (2013) manufacture and sale of the nutritional drink, BRAND’S Suntory PepsiCo Beverage (Thailand) Co., Ltd. -

Comparison of Sports Drink Products 2017

Nutritional Comparison of Sports Drink Products; 2017 All values are per 100mL. All information obtained from nutritional panels on product and from company websites. Energy (kj) CHO (g) Sugar (g) Sodium Potassium (mg/mmol) (mg/mmol) Sports Drink Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Blackcurrant 104 5.8 5.8 28.0 (1.2mmol) 33 (0.9mmol) Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Berry Ice 104 5.8 5.8 28.0 (1.2mmol) 33 (0.9mmol) Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Mountain Blast 105 5.8 5.8 28.0 (1.2mmol) 33 (0.9mmol) Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Lemon Lime 103 5.8 5.8 28.0 (1.2mmol) 33 (0.9mmol) Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Gold Rush 103 5.8 5.8 28.0 (1.2mmol) 33 (0.9mmol) Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Silver Charge 107 5.8 5.8 28.0 (1.2mmol) 33 (0.9mmol) Powerade Ion4 Isotonic Sports Drink Pineapple Storm (+ coconut water) 97 5.5 5.5 38.0 (1.7mmol) 46 (1.2mmol) Powerade Zero Sports Drink Berry Ice 6.1 0.1 0.0 51.0 (2.2mmol) - Powerade Zero Sports Drink Mountain Blast 6.8 0.1 0.0 51.0 (2.2mmol) - Powerade Zero Sports Drink Lemon Lime 6.8 0.1 0.0 56.0 (2.2mmol) - Maximus Sports Drink Red Isotonic Sports Drink 133 7.5 6.0 31.0 - Maximus Sports Drink Big O Isotonic Sports Drink 133 7.5 6.0 31.0 - Maximus Sports Drink Green Isotonic Sports Drink 133 7.5 6.0 31.0 - Maximus Sports Drink Big Squash Isotonic Sports Drink 133 7.5 6.0 31.0 - Gatorade Sports Drink Orange Ice 103 6.0 6.0 51.0 (2.3mmol) 22.5 (0.6mmol) Gatorade Sports Drink Tropical 103 6.0 6.0 51.0 (2.3mmol) 22.5 (0.6mmol) Gatorade Sports Drink Berry Chill 103 6.0 6.0 51.0 -

Red Bull Soapbox Race

SPECIAL EVENT : RED BULL SOAPBOX RACE ARIZONAARIZONA RHINORHINO TACKLESTACKLES REDRED BULLBULL TEMPETEMPE TOWNTOWN LAKELAKE RED BULL CARDBOARDCARDBOARD BOATBOAT SOAPBOX CHAMPCHAMP ENTERSENTERS SEATTLESEATTLE SOAPBOXSOAPBOX RACERACE RACE The only race where fast is by Glenn Miller, John Swauger good, outrageous is better. and Kaeryn Lapsley Swauger Seattle: September 29, 2007 Photography: RandallBohl.com he Emerald City will be seeing red at the start line of the Red Bull Soapbox T Race in Seattle on September 29. Speed and silliness are sure to be in abun- dance as non-motorized racers including a baby buggy, a Mellow Tubmarine and Fremont’s own landmark troll will maneu- ver a steep half-mile downhill course on Fremont Avenue (from 36th to 41st Streets) as they battle to beat the clock. After poring over nearly 300 applica- tions, 46 teams were chosen, along with a wildcard entry picked through online voting, to race their human-powered racing dream machines down the track. How may these gearheads achieve speedway stardom? Judging is based on three criteria: speed, creativity and showmanship. So you can’t just be fast… you have to be fast with flair. FULL HOUSE It’s a good thing the Fremont neighbor- hood offers the freedom to be peculiar, because no ordinary racers are likely to be hitting the track on race day. The lineup in Soapbox Seattle includes TV’s Bob Saget, KEEP RIGHT >> 30 • September-October 2007 • ARIZONADRIVER ARIZONADRIVER • September-October 2007 • 31 Tempe Town Lake 2004 : Photo by Glenn Miller Tempe Town Lake 2006 : Photo by Glenn Miller John has pulled out the tools before, John Wallick will be co-pilot. -

Obama Lauds CSU As Green University the Anchorage Daily News, Alaska’S Largest Newspaper, Endorsed Democratic Presidential Candidate Barack Obama

VOLLEYBALL FIGHTS INJURIES | PAGE 10 THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN Fort Collins, Colorado COLLEGIAN Volume 117 | No. 55 Monday, October 27, 2008 www.collegian.com THE STUDENT VOICE OF COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1891 UPDATE Latest poll results Source: http://www.cnn.com/ELECTION/2008/ National Poll Colorado Poll 6% 8% Obama BARACK THE OVAL McCain Unsure 43% 51% 40% 52% Latest campaign stops Source: http://projects.washingtonpost.com/2008-presidential-candidates/tracker/ John McCain - 4:15 p.m., Rally in Lancaster, Ohio Barack Obama – 3:30 p.m., Rally in Fort Collins, Colo. Latest Quote Source: http://labs.google.com/inquotes/ “Just this morning, Senator McCain said that actually he and President Bush ‘share a common philosophy.’” – Agence France-Presse OBAMA “Do we share a common philosophy of the Republican Party? Of course. But I’ve stood BRANDON IWAMOTO | COLLEGIAN up against my party, not just President Bush but Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Barack Obama looks over 50,000 supporters gathered in the CSU Oval Sunday. He highlighted the importance of funding education saying, “I don’t think the young people of America are a special interest group; I think they’re our future.” others, and I’ve got the scars to prove it.” MCCAIN – Reuters India Latest stories on Collegian.com Alaska’s largest newspaper endorses Obama Obama lauds CSU as green university The Anchorage Daily News, Alaska’s largest newspaper, endorsed Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama... By JIM SOJOURNER On Collegian.com The Rocky Mountain Collegian Tens of thousands jam park for Obama rally Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama brought his campaign back to Denver on Sunday.. -

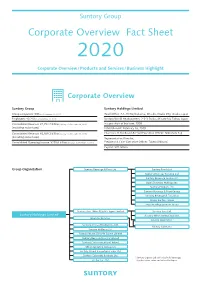

Corporate Overview Fact Sheet 2020

Suntory Group Corporate Overview Fact Sheet 2020 Corporate Overview/ Products and Services / Business Highlight Corporate Overview Suntory Group Suntory Holdings Limited Group companies: 300 (as of December 31, 2019) Head Office: 2-1-40 Dojimahama, Kita-ku, Osaka City, Osaka, Japan Employees: 40,210 (as of December 31, 2019) Suntory World Headquarters: 2-3-3 Daiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan Consolidated Revenue: ¥2,294.7 billion (January 1 to December 31, 2019) Inauguration of business: 1899 (excluding excise taxes) Establishment: February 16, 2009 Consolidated Revenue: ¥2,569.2 billion (January 1 to December 31, 2019) Chairman of the Board & Chief Executive Officer: Nobutada Saji (including excise taxes) Representative Director, Consolidated Operating Income: ¥259.6 billion (January 1 to December 31, 2019) President & Chief Executive Officer: Takeshi Niinami Capital: ¥70 billion Group Organization Suntory Beverage & Food Ltd. Suntory Foods Ltd. Suntory Beverage Solution Ltd. Suntory Beverage Service Ltd. Japan Beverage Holdings Inc. Suntory Products Ltd. Suntory Beverage & Food Europe Suntory Beverage & Food Asia Frucor Suntory Group Pepsi Bottling Ventures Group Suntory Beer, Wine & Spirits Japan Limited Suntory Beer Ltd. Suntory Holdings Limited Suntory Wine International Ltd. Beam Suntory Inc. Suntory Liquors Ltd.* Suntory (China) Holding Co., Ltd. Suntory Spirits Ltd. Suntory Wellness Ltd. Suntory MONOZUKURI Expert Limited Suntory Business Systems Limited Suntory Communications Limited Other operating companies Suntory Global Innovation Center Ltd. Suntory Corporate Business Ltd. * Suntory Liquors Ltd. sells alcoholic beverage Sunlive Co., Ltd. (spirits, beers, wine and others) in Japan. Suntory Group Corporate Overview Fact Sheet Products and Services Non-alcoholic Beverage and Food Business/Alcoholic Beverage Business Non-alcoholic Beverage and Food Business We deliver a wide range of products including mineral water, coffee, tea, carbonated drinks, sports drinks and health foods. -

Knowledge of and Attitudes to Sports Drinks of Adolescents Living in South Wales, UK RM FAIRCHILD

Knowledge of and attitudes to sports drinks of adolescents living in South Wales, UK R M FAIRCHILD BSc (Hons), PhD1 D BROUGHTON BDS (Hons) 2 M Z MORGAN BSc (Hons), PGCE, MPH, MPhil, FFPH2 1Cardiff Metropolitan University, Department of Healthcare and Food, Cardiff CF5 2YB 2Applied Clinical Research and Public Health, College of Biomedical and Life Sciences, Cardiff University, School of Dentistry, Heath Park, Cardiff CF14 4XY Key words: oral health, children, sports drinks Word count including abstract 2,399 Abstract – 270 Corresponding author: Ruth M Fairchild (Dr) Cardiff School of Health Sciences Department of Healthcare and Food Cardiff Metropolitan University, Department of Healthcare and Food, Western Avenue Cardiff CF5 2YB ABSTRACT Background: The UK sports drinks market has a turnover in excess of £200M. Adolescents consume 15.6% of total energy as free sugars, much higher than the recommended 5%. Sugar sweetened beverages, including sports drinks, account for 30% of total free sugar intake for those aged 11-18 years. Objective: To investigate children’s knowledge and attitudes surrounding sports drinks. Method: 183 self-complete questionnaires were distributed to four schools in South Wales. Children aged 12 - 14 were recruited to take part. Questions focussed on knowledge of who sports drinks are aimed at; the role of sports drinks in physical activity and the possible detrimental effects to oral health. Recognition of brand logo and sports ambassadors and the relationship of knowledge to respondent’s consumption of sports drinks were assessed. Results: There was an 87% (160) response rate. 89.4% (143) claimed to drink sports drinks. 45.9% thought that sports drinks were aimed at everyone; approximately a third (50) viewed teenagers as the target group. -

Cornwall South West Drinks Brochure 2016 Contents

LWC LWC Cornwall Depot South West Depot (Jolly’s Drinks) King Charles Business Park Wilson Way Old Newton Road Pool Industrial Estate Heathfield Redruth | Cornwall Newton Abbot | Devon TR15 3JD TQ12 6UT 0845 345 1076 0844 811 7399 [email protected] [email protected] ER SE SUMM ASON CORNWALL SOUTH WEST DRINKS BROCHURE 2016 CONTENTS Local Brands ���������������������������������������2-18 National Brands ������������������������������ 19-42 LWC ARE THE LARGEST INDEPENDENT WHOLESALER IN THE UK We currently carry over 6000 product lines But are you competitively priced? including: 127 different draught products of The last three years has seen us grow our sales beers, lagers and ciders from £110 million to £180 million this year� 1,212 different spirit lines We have only done this because we offer the best 740 soft drink lines balance of service, product range and price anywhere 1,035 different wines in the UK today� We are totally committed to 131 cider lines helping our customers grow their sales and 97 RTD’s margins through competitive pricing and a wide Over 1,000 different cask ales and varied product range� Are LWC backed and supported by Sounds good how do I get in touch? all national suppliers? Simple, for Cornwall call Naomi Mankee on LWC are partner wholesaler status with Coors, 0845 345 1076 or email cornwall@lwc-drinks�co�uk InBev and Heineken UK� We also work in for South West call Lucy Tucker on conjunction with ALL regional brewers in the UK� 0844 811 7399 or email southwest@lwc-drinks�co�uk This means that -

“Obesity - from Clinical Practice to Research” Donal O’Shea October 12Th 2013 IPNA, Athlone

“Obesity - from clinical practice to research” Donal O’Shea October 12th 2013 IPNA, Athlone. Outline of talk • A bit of background • Why we are where we are • A healthy lifestyle • Some of our research Obesity: like no previous epidemic • Diabetes • Cancer • Dementia • Cardiovascular Disease • Asthma • Arthritis Causes 4000 – 6000 Deaths per year in Ireland (Pop 5 million) Suicide deaths 486 (2011), Road deaths 161 (2012) Percentage increase in BMI categories since 1986 Sturm and Hattori, Int J Obes 2012 Body Mass Index 40 & 50 BMI 40 BMI 52 Body Mass Index 40 & 50 BMI 40 BMI 52 Guess 32 Guess 41 General facts • Average woman (5 ft 4) normal weight up to 10 stone (65 kilos) needs 1700-1800 kcal per day up tp 50yo then 1500kcal per day • Average man (5ft 10) normal weight up to12 stone (78 kilos) needs 1900-2000 kcal per day up to 50yo then 1700 kcal General Facts • From age of 4 to 14 child should be half age in stone General Facts • From age of 4 to 14 child should be half age in stone (depends on height) 4 year old – 2 stone 8 year old – 4 stone 14 year old – 7 stone And then they fill out….. Childhood Obesity in Ireland (and Europe) • 25% 3 year olds overweight/obese • 25% 9 years olds overweight/obese • low self image, concept and self esteem Growing up in Ireland 2009 Median BMI for each 5-year rise in age of onset of overweight O’Connell et al JPHN 2011 Young Scientist 2012 Age v Weight 75 70 65 60 55 50 45 40 Weight(kg) 35 30 25 20 15 4 4.5 5 5.5 6 6.5 7 7.5 8 8.5 9 9.5 10 10.5 11 11.5 12 12.5 13 13.5 14 Age • Study cohort - 6328 -

Long Term Sponsored By

SILVER Long term Sponsored by Lucozade Ogilvy & Mather Lucozade Sport: Longitudinal Case Study COMPANY PROFILE Ogilvy Ireland, part of Ogilvy worldwide is owned by WPP, the world’s second largest marketing communications organisation. The Ogilvy worldwide network includes 497 offices in 125 countries with 14,000+ employees working in over 50 languages providing Advertising, Promotions, Direct Marketing, Public Relations and Digital marketing services. Ogilvy & Mather Dublin, is one of Ireland’s largest advertising agencies handling a diverse portfolio of local Irish clients ranging from finance through major consumer brands to social marketing. INTRODUCTION AND BacKGROUND Launched in Ireland long before ‘Brand Beckham’ and the cult of the sports celebrity, Lucozade Sport recognized the potential in the growing trend for serious amateur participation in sport in Ireland as well as the influence that professional sport was having on amateur players and coaches. “Ten years ago you’d see lads on the team bus on the way up to Croker having a fag. You’d just never see that now” Dessie Dolan, Westmeath senior footballer (FBI Research, summer 2008). Sport is about results. So is this case Lucozade Sport pioneered a drinks category now worth more than €52 million. Before its launch sports drinks were virtually unknown, so our 157 SILVER challenge was to tap in to the hydration and nutrition needs of athletes who were just beginning to understand more about the demands placed on their bodies by sports. Importantly we also needed to establish Lucozade Sport as an Irish brand strong enough to withstand the threat of international brands like Powerade or Gatorade. -

Kuwait Dismayed by Cartoons, Rejects Islamophobic Offenses

RABIA ALAWWAL 8, 1442 AH SUNDAY, OCTOBER 25, 2020 16 Pages Max 34º Min 15º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 18266 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Egyptian official suspended for Egypt starts voting in first Syrians spruce up famed Real bounce back with 3 offensive remarks about Kuwait 5 stage of parliamentary polls 12 castle after years of war 16 rousing win over Barca Kuwait dismayed by cartoons, rejects Islamophobic offenses Some co-ops remove French products • Protesters in Irada Square slam Macron KUWAIT: The foreign ministry said on Friday mission’s position is “consistent and unwavering”, Kuwait has followed with deep dismay the contin- he added, as is the position of the government. ued circulation of caricatures lampooning Prophet “We do not accept such offenses under any cir- Muhammad (Peace Be Upon Him). In a press state- cumstances. The Kuwaiti mission continuously seeks ment, the ministry announced its backing of a to present and adopt decisions and initiatives at statement by the Organization of Islamic UNESCO that support peace, respect divine religions Cooperation (OIC), which expressed the Muslim and reject hostility and hatred. Last year, Kuwait’s del- world’s rejection of such offenses and practices. egation led an Arab and Islamic movement to approve The ministry warned about the danger of official a resolution at a UNESCO meeting condemning racist political discourses supporting such assaults on practices against Islam (Islamophobia), and it was religions or prophets. approved unanimously,” he said. Such acts instigate hatred, enmity, violence and The OIC earlier expressed strong indignation at undermine international efforts to promote the val- the publication of the caricatures depicting the holy ues of tolerance and peaceful coexistence, the min- Prophet (PBUH), lashing out at French officials for istry argued. -

Dr. Hamid Doost Mohammadian Principles of Strategic Planning

Dr. Hamid Doost Mohammadian Principles of Strategic Planning Principles of Strategic Planning By: Dr. Hamid Doost Mohammadian 01. Auflage (2017) ©2017 Fachhochschule des Mittelstands GmbH, Bielefeld. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Nachdruck, auch auszugsweise, sowie Verbreitung durch Film, Funk, Fernsehen und Internet, durch fotomechanische Wiedergabe, Tonträger und Datenverarbeitungssysteme jeder Art nur mit schriftlicher Genehmigung. FHM-Verlag Bielefeld, Ravensberger Str. 10 G, 33602 Bielefeld ISBN-Nr.: 978-3-937149-64-6 www.fh-mittelstand.de Introducing myself When I was a child, I had lots of cars, trains, ships and robot toys. I was so interested in playing, taking apart and fixing them. Besides this, while playing with my friends, I was the one who took over the role of the story teller of the game who told the others the content of the play and managed to give the others their role. When growing up, I chose Physics, Mathematics and Informatics as my major subjects at High School where I became the best pupil at class, school and local region. Afterwards, I chose to study Engineering in the field of Computer Hardware. The undergraduate program at Shahid Beheshti University (SBU) is a well-rounded program. It did not only help me to build a solid foundation of Computer Engineering fundamentals, but also helped me to develop an overall perspective of the vast field of Engineering. I have striven to perform well in all courses. My Bachelor thesis topic was “Designing an Intelligent Systems for Marketing of Oil Products for Iran Petrochemical Commercial Company” and I was interested in Neural Nets, Genetic Algorithms, Modelling and Simulation and I was interested in Industries and Energy so, I chose the numerical simulation of activity around a transportation system, Management, as my final thesis. -

Suntory Holdings Limited

Suntory Holdings Limited August 5, 2016 SUMMARY OF CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE SIX MONTHS ENDED JUNE 30, 2016 (English Translation, UNAUDITED) Company Name: Suntory Holdings Limited (URL: http://www.suntory.com/) Representative: Takeshi Niinami, President Contact: Toru Niwa, Head of Public Relations Public Relations Office: Tel:+81(0)3 5579-1150 Tel:+81(0)6 6346-0835 (Fractions of millions have been truncated) 1. Consolidated operating results and financial positions for the six months of the current fiscal year (January 1, 2016 - June 30, 2016) (1) Operating results (% figures represent change from the same period of the previous fiscal year) Net income attributable Net sales Operating income Ordinary income to owners of parent Six months ended \million% ¥ million % \million % \million % June 30, 2016 1,273,069 3.0 87,277 14.0 75,647 14.2 35,633 129.5 June 30, 2015 1,236,336 11.5 76,527 18.8 66,238 6.0 15,529 (9.7) Referential Information : Income before amortization of goodwill and others Net income attributable Operating income Ordinary income to owners of parent Six months ended ¥ million % \million % \million % June 30, 2016 121,387 10.3 109,758 10.0 63,476 44.4 June 30, 2015 110,049 31.499,759 21.9 43,943 40.2 Note:Income before amortization of goodwill and others = Income + Amortization of Goodwill, Trademarks and other recognized in connection with M&A Diluted net income per Basic net income per share share Six months ended ¥ ¥ June 30, 2016 52.11 - June 30, 2015 22.73 - (2) Financial positions Ratio of equity Total